Posts Tagged ‘unauthorized biography’

BIO Award Winner Kitty Kelley’s Speech

Kitty Kelley won the 2023 Biographers International Organization Award. On Saturday, May 20, at the 2023 BIO Conference, it was also announced that Kelley will make a gift of $1 million to BIO, to be given over the course of five years. You can read more about that here.

The following is Kitty’s keynote address:

If I get run over tonight, please make sure that this BIO award leads my obit, because it’ll be the only time that my name shares the same space with Ron Chernow and Robert Caro and Stacy Schiff. But I don’t want to think about obituaries right now. I want to share with you a little bit about the writing life that brings me here today.

I love books and as much as I enjoy fiction, I bend my knee to nonfiction, particularly biography—the art of telling a life story. All kinds of life stories—memoir, authorized and unauthorized biography, historical narrative, or contemporary profiles.

In the last few decades, I’ve written biographies about living icons, a genre that is sometimes dismissed as “unauthorized biography” and, unfortunately, the term is sometimes said as if you’re emptying a bedpan or cleaning up the dog’s mess. Unauthorized biographies are not approved by everyone and rarely appreciated by their subjects. One exception, of course, is the New Testament, which was written by disciples who never knew their subject.

About 40 years ago, I thought I’d died and gone to biography heaven when Bantam Books offered me a grand advance to write the unauthorized biography of Frank Sinatra. I’d written two previous biographies and been robbed on both. On the first one, I didn’t have an agent—which is like driving a car without a steering wheel. On the second, I had an agent straight out of Oliver Twist. You may remember the woman who advised Linda Tripp to advise Monica Lewinsky to save her blue dress. Well, that same woman was once a literary agent who caused about $70,000 in foreign sales to go missing on my Elizabeth Taylor biography. My lawyer was incensed and insisted I sue. I told him to write the agent, say I’d misplaced records, and ask for another accounting. I figured that way she could correct herself and repay the missing monies.

I’m embarrassed to admit that I let this go on for over a year because I just couldn’t believe a literary agent would steal from a client. My lawyer said, “Try to get it into your fat head: She’s not Max Perkins. She’s Ma Barker.”

After 17 months, I finally filed suit. Depositions were taken and the case went to federal court in Washington, D.C. I fully expected her to settle because the evidence was so overwhelming. Instead, the case went to trial and the jury found Ma Barker guilty on all six counts, including fraud. They demanded she make payment on the courthouse steps and even asked for punitive damages.

I suppose the lawsuit was a great victory, because I unloaded a bad agent and got a good one, but I was in no hurry to do another biography. I’d just learned the hard way that there’s no education in the second kick of a mule. I’d undertaken the Elizabeth Taylor biography, hoping to write about the Hollywood studio system that had shaped our fantasies for most of the 20th century. I envisioned weaving that theme into the life story of Elizabeth Taylor, who grew up as a little girl at MGM, and went to school at MGM and . . . married many MGM men. But my plan for this historical narrative soon got buried in Ms. Taylor’s Technicolor life of husbands and hospitals and jewelry stores.

My agent asked, if I were to consider writing another life story, who would be of interest? I said, “Well, the gold ring on the merry-go-round would be Frank Sinatra, because no one’s really done it, and he epitomizes the American dream.” She agreed and that was the end of the subject until a couple weeks later when she called and said she had a generous offer from Bantam Books.

Soon I was back in the biography business, thinking I’d paid my hard luck dues. I’d had a bandit publisher on my first book and a thieving agent on my second. Now was third time lucky. And for a few weeks it was . . . until I was served a subpoena from Frank Sinatra, announcing that he was suing me for $2 million dollars for usurping the rights to his life story. He claimed that he and he alone (or someone he authorized) was entitled to write his life story, and I certainly had not been authorized.

I immediately called my publisher, and Bantam’s legal counsel informed me that I was on my own. “Mr. Sinatra has not sued us,” she said. “He’s sued you, and since you’ve not given us a manuscript, we’re not involved. So, I’d advise you to get legal counsel in California, which is where you’ve been sued and do keep us informed.”

“But I haven’t written a word. I’ve only just begun. My manuscript is years away.”

“We’ll talk then,” she said, before hanging up.

Now, getting sued by a billionaire with Mafia ties concentrates the mind, especially after your publisher leaves the scene. I called my friend, the president of Washington Independent Writers, to commiserate. “I wish we could help you, Kitty, but we’re almost broke,” she said. I assured her that I wasn’t looking for money—just moral support. “Well, in that case, let me get on the horn.” She contacted several writers’ groups, including the Authors Guild and PEN and the American Society of Journalists and Authors, and Sigma Delta Chi, and the National Writers Union. Days later, they held a press conference at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., to denounce Sinatra for using his power and influence to intimidate a writer before she’d written a word. They denounced his lawsuit and his assault on the First Amendment. As journalists, they understood what was at stake if Sinatra prevailed.

I retained the law firm of O’Melveny and Myers in Los Angeles and tried to keep working on the book, but was interrupted a few weeks later when I was in New York doing interviews and my lawyer called to tell me to get back to D.C. because the LA lawyers were coming to Washington for a meeting that would also be attended by my publisher. The LA lawyers said they’d received a tape recording from Sinatra’s lawyers of me supposedly misrepresenting myself as Sinatra’s authorized biographer, and this tape recording was the proof that they were going to present in court.

Now I was scared, even though I knew I hadn’t made such a telephone call. But I began to second-guess myself, wondering if maybe under the pressure I’d snapped my cap. By the time the lawyers arrived that Monday morning I was ready for handcuffs.

Three teams of lawyers sat down in my living room and put the tape in the recorder. No one said a word for the first two minutes because what we heard sounded like Porky Pig flying high on helium. In a squeaky voice, Porky said he was me and Frank Sinatra told me to call for an interview. The lawyers played that tape three times and we all listened to Porky Pig again and again before anyone said a word. Then all the lawyers laughed, clearly relieved, knowing the tape was a phony. I didn’t laugh.

“This lawsuit has gone on for almost a year and now someone is willing to lie under oath to say that I misrepresented myself to get an interview.”

“Don’t worry. We’ll send this to the tape labs at U.S.C., they’ll send the report to Sinatra’s team, and we’ll file for a dismissal. Meantime, just tape all your interviews.”

I tried to explain to the lawyers that you couldn’t always tape interviews, especially in the early 1980’s, when the technology wasn’t sophisticated. Taping in restaurants was difficult over the clinking of glasses, and taping phone interviews wasn’t legal in every state, even with two-party permission.

I finally decided that the best way to protect myself was to write a thank-you note to everyone I interviewed. That turned out to be 800 notes. They were polite and also protective. I’d thank them for the time they gave me in their home or their office or their favorite bar—wherever we’d done the interview; I’d compliment them on the polka dot bow tie they wore or the pretty pink blouse or their red tennis shoes; I’d mention the fabulous décor, or a particular piece of art, or our great salad in such-and-such a restaurant—any detail that set the time or place. Then I’d send it off and keep a copy in my files, because three or four years later when the book was finally published, they might very well have forgotten that interview or, more likely, wish they had.

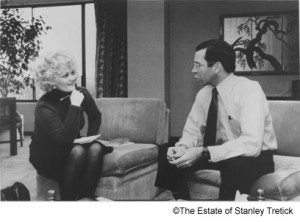

That happened with Frank Sinatra Jr. He’d agreed to be interviewed when he was performing in Washington, D.C. His representative asked if I’d be bringing a camera crew, and I said no crew, just a still photographer. Then I quickly called my friend Stanley Tretick, one of President Kennedy’s favorite photographers who had worked for UPI and then LOOK magazine.

Stanley and I arrived at the Capitol Hill Hilton in the afternoon and went to Sinatra’s suite. His publicist met us and then disappeared when Frank Jr. entered the room. Sinatra’s only son sat down and asked me to sit close to him because he didn’t want to strain his voice. He was performing that night. So, I moved over, notebook in hand. The first 30 minutes of the interview went well as Sinatra Jr. talked about accompanying his father on tour and hanging out in Vegas with his father’s friends. Then he leaned over and said, “Hon, I know what happened to Jimmy Hoffa.”

I didn’t move. Because no one knew what happened to Jimmy Hoffa. They knew he was dead, but they didn’t know how or by whom. And now the son of a mob-connected man was going to tell me.

For a split second I wondered what I should wear when I got the Pulitzer Prize.

Just as Frank Sinatra Jr. leaned over to whisper in my ear, Stanley dropped his camera bags on the floor, and said, “Well out with it, man. What the hell happened to Hoffa?”

Frank Sinatra Jr. reared back as if he’d been clubbed. He looked at me, then he bolted from his chair and ran into the bedroom, slamming the door. His publicist came running out and said we had to leave. I begged for more time, saying the interview wasn’t finished, but the publicist was physically pushing us out the door.

Up to that point, Stanley Tretick had been one of my closest friends. Now I looked at him as if he’d just been possessed by the Tasmanian devil.

“Aw, hell. He doesn’t know what happened to Jimmy Hoffa.”

“Really?” I said. “And since when are photographers clairvoyant? And what kind of a lunkhead photographer throws a hissy in the middle of a reporter’s interview? Did it ever occur to you that what the son of a mob-connected man has to say about the disappearance of Jimmy Hoffa might be of interest?”

By now I was down the steps and storming the street to hail a cab. I refused to ride in the same car with a crazy person when I was homicidal. I didn’t speak to Stanley for some time, but he became my best pal again when the Sinatra biography was published. By then Frank Sinatra had dropped his lawsuit but his son now decided to sue, denying he’d ever given me an interview. His lawyers contacted my publisher and everyone braced for another lawsuit. But Stanley produced one of the photos he’d taken during our interview that showed me sitting next to Frank Sinatra Jr. with a notebook in [my] hand and a tape recorder on the table.

That photograph certainly trumped all of my little thank-you notes. Yet I can’t tell you how many times those notes saved me. When I wrote the Nancy Reagan biography, letters rained down on Simon & Schuster from corporate tycoons and all manner of political operatives, who took offense with the words attributed to them or to their wives or secretaries or associates, and at the bottom of every letter was a “cc” to President Ronald Reagan. Each time the publisher’s lawyer would call me to go over my notes and my tapes, and then he’d send a courteous reply, saying the publisher stands by the book and its accuracy.

At first, I wanted the publisher to “cc: President Reagan” just like all the letter writers had done, but the lawyer said no reason to stir the beast. “Those are weasel letters. They’re sent simply to show the flag.” He was right, and there were no retractions and no lawsuits.

That controversial biography became the cover of Time, Newsweek, People, Entertainment Weekly, and The Columbia Journalism Review, and [was] presented on the front pages of The New York Times, The New York Post, and the New York Daily News.

On the day of publication, President and Mrs. Reagan held a press conference to denounce the book, saying that I had—quote—“clearly exceeded the bounds of decency.” And three days later, President Richard Nixon agreed. President Nixon wrote a letter to President Reagan to commiserate. President Reagan responded, saying that everyone he knew had denied talking to the author. Reagan even named the minister of his church, who’d been cited as a source, and the minister had written a denial to all his parishioners in the Bel Air Presbyterian Church bulletin.

Now, I really tried not to respond to every accusation, but this one from a man of the cloth got to me, and I wrote to remind him of the 45 minute interview he’d given in his office. I enclosed a transcript of his taped remarks and asked him to please send around another church bulletin—with a correction. Of course, he didn’t, which proves the wisdom of Winston Churchill, who said that a lie flies halfway around the world before the truth gets its pants on.

Having rankled President Reagan and President Nixon, I later rattled President George Herbert Walker Bush. I’d written to him as a matter of courtesy, when I was under contract to Doubleday to write a historical retrospective of the Bush family, and said I’d appreciate an interview sometime at his convenience.

President Bush never responded to me but he directed his aide to write my publisher, saying:

“President Bush has asked me to say that he and his family are not going to cooperate with this book because the author wrote a book about Nancy Reagan that made Mrs. Reagan unhappy.” First Lady Barbara Bush had been so incensed when she saw my books displayed in the First Ladies Exhibit at the Smithsonian that she directed the curator to remove the display, which he did the next day. In fact, I might not have known about it had I not taken my niece to the Smithsonian a few weeks before and we’d seen the display and took a picture of it.

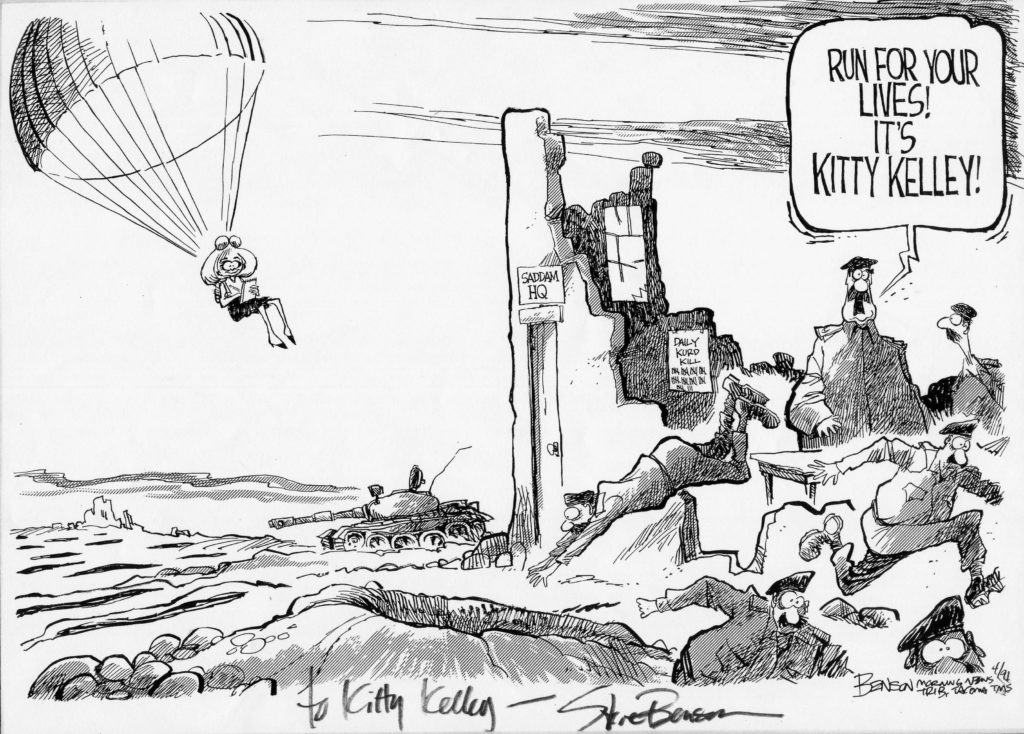

That photograph now hangs in my guest bathroom next to autographed cartoons from Jules Feiffer and Garry Trudeau. Over the years, that loo has become crowded with cartoons from all of my various books. My sister was very impressed when she saw them. She said to my husband, “I think it’s great that Kitty has put up all the bad ones.” My husband said, “There were no good ones.”

My biography on the Bush family dynasty was published in 2004, in the midst of a contentious presidential campaign. Bush Jr. was running for a second term, and I was lambasted by his White House press secretary, the White House deputy press secretary, the White House communications director, the Republican National Committee, and the house majority leader, Tom DeLay. Mr. DeLay even wrote a colorful letter to my publisher, saying that I was—quote—“in the advanced stage of a pathological career” and the publisher was in—quote—“moral collapse for publishing such a scandalous enterprise.”

When the Bush book became number one on the New York Times bestseller list, I was dropped from the masthead of The Washingtonian Magazine, where I’d been a contributing editor for 30 years. The new owner of the magazine was a Bush presidential appointee. The editor told me, “Your book was too personal. Too revealing.”

“But that’s what a biography is,” I said. “It’s an intimate examination of a person in his times, and in this case a powerful person in the public arena. The President of the United States influences our society, with actions that affect our lives.”

I quoted the actor Melvyn Douglas from the movie Hud. He talked about the mesmerizing power of a public image: “Little by little the look of the country changes because of the men we admire.” And Colum McCann, in his novel Let the Great World Spin, wrote: “Repeated lies become history, but they don’t necessarily become the truth.”

This is why biography is so vital to a healthy society. Whether authorized or unauthorized, biography presents a life story—sometimes it’s an x-ray of a manufactured image, sometimes it’s a gauzy bandage. The best biographers try to penetrate dross and drill for gold. As President Kennedy said, “The great enemy of the truth is very often not the lie—deliberate, contrived and dishonest—but the myth, persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic.”

I do not relish living in a world where information is authorized, sanitized, and homogenized. I read banned books. I applaud whistleblowers and I reject any suppression by church or state. To me, the unauthorized biography, which requires a combination of scholarly research and investigative reporting, is best directed at those figures still alive and able to defend themselves, who exercise power over our lives. . . . I firmly believe that unauthorized biography can be a public service and a boon to history.

The most solid support I’ve received over the years has come from writers—journalists and historians and biographers—who believe in the First Amendment. Who champion the public’s right to know.

These are principles that feed my soul and fill my heart, which is why I’m so grateful to be honored by you today with this award.

Thank you.

BIO Podcast

Kitty Kelley spoke with BIO member John A. Farrell in February 2020 in Washington, D.C.

Kitty Kelley spoke with BIO member John A. Farrell in February 2020 in Washington, D.C.

Part I (26:53):

Part II (26:26):

John A. Farrell’s website: http://www.jafarrell.com/

Biographers International Organization: https://biographersinternational.org/

BIO Podcasts: https://biographersinternational.org/podcasts/

Part I URL:

https://biographersinternational.org/news/podcast/podcast-episode-45-kitty-kelley-part-i/?fbclid=IwAR0N2CMGj5Fzg5bY4Rx1VsXkGCd2HHri1K0jOKHbgf8x4uJlIwGliZWGlFI

Part II URL:

https://biographersinternational.org/news/podcast/podcast-episode-46-kitty-kelley-part-ii/?fbclid=IwAR1xJI97oOu5YbQSP2_4M6dl1DABV7g12Wnzcjp2MpdbU4fr5tHY3683kOg

BIO Board of Directors

- Linda Leavell, President (2019-2021)

- Sarah S. Kilborne, Vice President (2020-2022)

- Marc Leepson, Treasurer (2019-2021)

- Billy Tooma, Secretary (2020-2022)

- Kai Bird (2019-2021)

- Deirdre David (2019-2021)

- Natalie Dykstra (2020-2022)

- Carla Kaplan (2020-2022)

- Kitty Kelley (2019-2021)

- Heath Lee (2019-2021)

- Steve Paul (2020-2022)

- Anne Boyd Rioux (2019-2021)

- Marlene Trestman (2019-2021)

- Eric K. Washington (2020-2022)

- Sonja Williams (2019-2021)

What It’s Like to Be Kitty Kelley

Originally published in Washingtonian October 2019

I’ve been in DC since, let’s see . . . since Abraham Lincoln was President! I came to help with Senator Eugene McCarthy’s Foreign Relations Committee mail for a six-week stint, but I ended up in his Senate office and stayed four years. I remember that his personal secretary, who looked like she had been on the job 102 years, took one look at me and said, ‘Can she type or take shorthand?’ McCarthy replied, ‘We don’t ask the impossible of anyone around here.’ I thought, This guy has got a great sense of humor.

When I left the Hill in 1968, I became the researcher for the Washington Post editorial page. After two fabulous years at the paper, I got a book contract to investigate the beauty-spa industry. Since I weighed three pounds less than a horse, I signed fast and saddled up to visit every fat farm in the country. I got myself down to pony size, and the book probably sold 14 copies—all to my mother.

Then I backed into writing biographies, beginning with Jackie Oh! I love the genre, but writing an unauthorized biography brings its challenges. The subjects I’ve chosen are extremely powerful public figures who’ve had a vast impact on our lives and are fully invested in their images. Consequently, the blowback can be considerable.

I remember when my Nancy Reagan book came out in 1991, my late husband, John, who was courting me at the time, took me to Bice, then a real hot spot in DC. As we walked in, a man stood up and started yelling, ‘Booooo! Get that bitch out of here! Boo! Boo!’ John turned around to see who the guy was yelling at. I knew and looked straight ahead, praying not to cry. The man kept yelling, everyone turned to look, and then a woman on the other side of the restaurant started yelling, ‘No, no—she’s brave!’ The two of them went at each other, and the restaurant suddenly looked like tennis at Wimbledon, turning from one side to the other. The maître d’ brought us to a table, and John buried himself in the wine list. Then a guy from the middle of the room threw his napkin on the floor and headed for our table. I thought for sure we were goners. He spread out his arms and embraced me: ‘Kitty, you don’t know me, but I’m going to stand here until this stops.’ It was Tony Coehlo, the majority whip in the House of Representatives. I introduced him to John, who said, ‘Congressman, you go in the will.’ John told me later he was going to propose over dinner but was so flummoxed by what happened, he put it off for 24 hours.

My Bush-family book drew fire from the White House, the Republican National Committee, and the GOP leader in the House of Representatives. I framed all the cartoons and hung them where they belong—in the loo. My favorite is the bubble-headed blonde in Chanel shoes parachuting into Saddam Hussein’s bunker, scattering the armed guards, who yell, ‘Run for your lives! It’s Kitty Kelley!’

I don’t write about just anybody. I only choose huge figures who have manufactured a public image. I’m fascinated to find out what they’re really like. I’m not doing another great big bio simply because, at this moment in time, I don’t want to know what anyone out there is really like. Certainly not Trump. Melania? Oh, definitely not.

I’ve already done seven New York Times bestsellers. I can’t say that I loved doing them, but I sure loved finishing them.

The Vanity Fair Diaries: 1983-1992

by Kitty Kelley

The British excel as diarists, the most famous being Samuel Pepys, followed by James Boswell (the biographer of Dr. Johnson), and Virginia Woolf, the beacon of the Bloomsbury Group. Currently, Alan Bennett, 83, reigns supreme.

The British excel as diarists, the most famous being Samuel Pepys, followed by James Boswell (the biographer of Dr. Johnson), and Virginia Woolf, the beacon of the Bloomsbury Group. Currently, Alan Bennett, 83, reigns supreme.

Now comes Tina Brown pawing at that pedestal with The Vanity Fair Diaries: 1983-1992, which chronicles her glory days as the English editor who came to America to revive the magazine, and later to resuscitate the New Yorker. For this she deserves heaps of Yankee praise.

Once I got my mitts on her book, I did what everyone will do: I turned to the index. Back in 1989, I was lucky enough to be selected along with Ted Turner, Diane Sawyer, Steven Spielberg, and others (plus the tombstone of Andy Warhol) as part of “the Media Decade” in Vanity Fair’s Hall of Fame. Each of us was photographed by Annie Leibovitz, who signed and sent originals of the shots as Christmas presents. I was curious to see if the diaries mentioned that 40-page spread in the magazine.

Flipping to the back of the book, I see one entry on page 347 about “the biggest media influencers” of the era. Wowza. There I am. Whoops. “Trashy Biographer Kitty Kelley.” But I’m not alone. Similar smackdowns await others.

Brown zings Jerry Zipkin, “always in high malice mode” as “Nancy Reagan’s viperish portly walker.” She cuffs Charlotte Curtis, the New York Times editor, as “unbearable,” adding, “What a bogus grandee she is, a coiffed asparagus, exuding second-rate intellectualism.”

She bashes Oscar de la Renta as a “conniving bastard,” but after a kiss-and-make-up lunch, she sees “a nicer side of Oscar at last.” Arnold Scaasi is “the dreaded frock miester,” and Richard Holbrooke “an egregious social climber.”

After inviting Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis to a dinner party in honor of Clark Clifford, Brown dings the former First Lady (“Jackie Yo!”) as “crazed,” writing: “I felt if you left her alone, she’d be in front of a mirror, screaming.” Then she zaps Onassis for “understated malice” in not “writing me a thank you note.”

Midway through these diaries, you might think that most of Brown’s roadkill has been gathered up and gone to the angels. Given the passage of time, some attrition among the grandees of Gecko greed is understandable, but one wonders if Brown would’ve disparaged Si Newhouse, her billionaire benefactor at Conde Nast, as “a hamster,” an insecure “gerbil” frequently in “chipmunk mode,” if he were still alive. Safely dead, he gets blasted for having “no balls at all” because he caved to Nancy Reagan’s request to see Vanity Fair’s profile of her and the president before publication.

Read on, though, and you’ll see that Brown’s slingshot takes equal aim at those not yet consigned to the cemetery. Kurt Vonnegut’s photographer wife, Jill Krementz, is zapped for “extreme pushiness”; Henry Kissinger “is a rumbling old Machiavelli”; Peter Duchin “name drop[s] at deafening volume”; Robert Gottlieb, Brown’s predecessor at the New Yorker, is “a preposterous snob”; and Clint Eastwood is an excruciating bore.

“How could one be bored after one course with the world’s biggest heartthrob?” she asks. “I was.”

She cuffs her former friend Sally Quinn for disinviting her to Ben Bradlee’s birthday party because of Vanity Fair’s book review by Christopher Buckley, who characterized Quinn’s first novel as “cliterature.” Sally was “wild with fury,” Brown writes, a bit puzzled that “the sharpshooter journalist,” who had once libeled Zbigniew Brzezinski, would be so sensitive.

(In a profile for the Washington Post, Quinn wrote that Brzezinski, then national security advisor to President Carter, had unzipped his fly during an interview with a female reporter from People, which Quinn claimed had been captured by a photographer. The next day, the Washington Post retracted her false story: “Brzezinski did not commit such an act, and there is no picture of him doing so.”)

Brown does not chop with a cleaver. She wields her scalpel with surgical precision, blood-letting with small, incisive cuts. She doesn’t linger over the corpse, either. In fact, in these diaries, she jumps from mourning the death of a friend one day to tra-la-la-ing the next as she sits with Vogue’s Anna Wintour, drawing up guest lists for yet another dinner party.

Brown makes intriguing entries about New York’s new-money barons, particularly Donald Trump, who keeps a collection of Hitler’s speeches in his office. On February 23, 1990, she writes that Trump, in between wife number one and two, is “having a fling with a well-known New York socialite. If true, this could give Trump what money can’t buy — the silver edge of class.”

Alas, she doesn’t reveal the name of the silver belle, but she does relate that Trump, enraged by Marie Brenner’s 1988 takedown of him in Vanity Fair, sneaks behind her at a black-tie gala and pours a glass of wine down her back.

One marvels at Brown’s indefatigable energy as she sprints from breakfast with Barry Diller to lunch with Norman Mailer to dinner with the Kissingers. Every day, every night: the parties, the premieres, the galas, the spas, the stylists, the hairdressers, the designers, the limousines. Even she admits exhaustion at her frantic drive to see and be seen — all in service to her role as editor, of course.

These diaries are a celebrity drive-by of the great and the good and, sprinkled with high and low culture, are written with style but little humor, save for the night the newly arrived London editor attended her first Manhattan cocktail party and met Shirley MacLaine.

“What do you do?” Brown asked the movie star. This is laugh-out-loud funny, except to someone who’s laughed in many previous lives. MacLaine was not amused. Upon meeting Lana Turner when the MGM siren was 62, Brown, then 29, decides to “get a piece done that uses her [Turner] as a prism for all the glamorous stars who age without pity.”

The British writer Graham Boynton, who applauds Brown’s high-octane journalism, wrote affectionately in the Telegraph about her early days editing Vanity Fair. Reading a submitted draft for the Christmas issue, she scribbled, “Beef it up, Singer.” Boynton recalled, “It had to be tactfully explained to her that Isaac Bashevis Singer was a Nobel Prize winner for literature.”

I’m knocked out by these diaries, marveling that they were written at the time in such perfect prose. Do all her sentences fall to the page like rose petals in a summer breeze? No editing? No rewriting? No tweaking? If so, this “trashy biographer” genuflects. (My own diaries read like the daily romps of an unhinged mind scrambling for cruise control.)

Diaries provide a psychological X-ray of the diarist, an unintentional autobiography of sorts, and these entries show a woman of immense talent consumed with her dazzling career. And as tough as she is (and must be) in a man’s world, her feminist self resents being dismissed.

When Ad Age demeans her as a “starlet wanting to play Juliet,” she punches back. It’s “fucking sexist crap,” she writes. “Women get stuck with being trivialized and just have to smile.”

Flicking off such criticism like a fuzzball from cashmere, Tina Brown smiles all the way to the bank and then rockets upward, leaving the rest of us in her high-heeled wake

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Vanity Fair December 1989

The 1989 Hall of Fame – The Media Decade

Star Sleuth Kitty Kelley

“Catty Kitty stalked the four great beasts of the celebrity jungle—Jackie, Nancy, Liz and Frank. Doing it her way, she clawed past hostile flacks and stonewalling cronies….”

Washington Independent Review Lifetime Achievement Award

Kitty Kelley received the 2016 Lifetime Achievement Award from the Washington Independent Review of Books. The award was presented at the 4th annual “Books Alive!” Washington Writers Conference on April 30, 2016. The following are her remarks.

For the last 40 years I’ve chosen to write biographies of people who are alive and influence our world. I’ve done this without their cooperation and independent of their demands and dictates. These people are not simply celebrities, but titans of society who have affected us as individuals and left an imprint on our culture, sometimes for better, sometimes for worse.

With each biography, the challenge has been to answer the question John F. Kennedy once posed: “What makes journalism so fascinating and biography so interesting is the struggle to answer that single question: ‘What’s he like?’”

I believe that the best way to find out is to tell a life story from the outside looking in, and so I choose to write with my nose pressed against the window rather than kneeling inside for spoon feedings.

Championing the independent or unauthorized biography might sound like a high-minded defense for a low-level pursuit, but I do not relish living in a world where information is authorized, sanitized and homogenized. I read banned books. I applaud whistleblowers. I reject any suppression by church or state. And I believe in freedom of the press. To me the unauthorized biography, which requires a combination of scholarly research and investigative reporting, is best directed at those figures, still alive, who exercise power over our lives.

In writing about contemporary figures, I’ve found that the unauthorized biography avoids the pureed truths of revisionist history, which is the pitfall of an authorized biography. Without being beholden to the subject or bending to editorial control, the unauthorized biographer is better able to penetrate the manufactured public image. For, to quote President Kennedy again, “The great enemy of the truth is very often not the lie—deliberate, contrived and dishonest—but the myth—persistent, persuasive and unrealistic.”

Despite my lofty defense of the unauthorized biography there’s no question that it exacts a price. The authorized biographer is often hailed as a white knight while the unauthorized biographer is usually demonized. It’s the difference between poodles and pit bulls. One is adored—the other avoided. Authorized biographers are like seraphim—the angels who stand to give praise. Unauthorized biographers are like what John Boehner recently called Ted Cruz. You can understand why I keep an old cowboy motto above my desk that says—“Tell the truth but ride a fast horse.”

I still dream about going to the same heaven as authorized biographers but I’m probably headed for whatever awaits the unanointed. I’m afraid I’ve toiled too long on the unauthorized side of the street to ever hear the angels sing. But this award for telling the truth and riding a fast horse will keep me galloping forward —with great pride.

Thank you very much.

(All photos by Bruce Guthrie.)

David O. Stewart, president and chair of the board, presented the award to Kitty Kelley.

Kitty Kelley with keynote speaker Bob Woodward.

Kitty Kelley on Frank Sinatra

Who would’ve thought that we’d be here tonight celebrating the 100th birthday of Frank Sinatra???

Some of you were with me thirty years ago when I was researching his life story and Sinatra sued to stop me. He said then that only he alone or someone he authorized had the right to write about his life. The day he hit me with his $2 million lawsuit was the day I fully understood what the First Amendment was all about.

it hadn’t been for the support I received from writers groups around the country like the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, Sigma Delta Chi, the Newspaper Guild, PEN, the American Society of Journalists and Authors, the National Writers Union, the Council of Writers Organizations and Washington Independent Writers, I could not have written this book. So I remain profoundly grateful to those writers who understood how a powerful man with money and influence could try to exercise prior restraint and bury a writer before she had written a word.

After a year-long battle Frank Sinatra finally dropped his lawsuit and His Way: the Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra was published. Now it’s been updated and re-released to coincide with his centennial.

For me the best part of tonight is that the life story of a man with only 47 days of education before he dropped out of high school in Hoboken, New Jersey will benefit Reading is Fundamental. This organization is the largest non-profit for children’s literacy in the United States. So the more books you buy tonight, the more books Reading is Fundamental can put in the hands of poor children who’ve never owned a book. Possessing their own books will help them learn to read and to become literate, and their literacy will benefit all of us. Now even Frank Sinatra could not object to that.

So let’s hoist a glass to Ole Blue Eyes and to the First Amendment and to all those who made this evening possible.

Kitty Kelley made these remarks at a party and book signing celebrating the release of the Frank Sinatra centennial edition of His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra. The event took place on December 9, 2015 at i Ricchi restaurant in Washington DC.

Statement, ASJA Awards Presentation, April 24, 2014

On April 24, 2014, Kitty Kelley was presented with the Founders’ Award for Career Achievement by the American Society of Journalists and Authors (ASJA) during a ceremony at the group’s 43rd annual writers’ conference in New York. The following are her remarks at the Awards Presentation.

My love affair with the American Society of Journalists and Authors began on September 21, 1983 when we were introduced by Frank Sinatra. That was the day he sued me for $2 million to keep me from writing his (decidedly unauthorized) biography. In court papers, he declared that he and he alone or someone that he authorized could write his life story. No one else was entitled to what he called his “right of publicity.”

ASJA immediately stepped forward and joined with other writers’ groups to protest Sinatra’s assault on the First Amendment. In a press conference, they said: “The apparent goal behind Sinatra’s filing of this suit is to scare Ms. Kelley away from her investigation and ultimately to force her to scrap the book.” They asserted that “the unauthorized or unblessed biography” is the essence of free speech and open commentary and declared that Sinatra’s lawsuit was an assault on all writers’ constitutionally protected freedom of expression and should be dismissed on its face.

This public stance stirred a great deal of publicity from outraged journalists, who wrote columns, editorials, and even a few cartoons. One of the funniest was drawn by Jules Feiffer, who showed a mug’s face under a snap-brim hat, swaying on skinny legs and snapping his fingers:

showed a mug’s face under a snap-brim hat, swaying on skinny legs and snapping his fingers:

“I’m chairman of the Board. If some broad wantsa write a book about me… She gotta talk t’one of my boys who talks t’one of my other boys… who talks t’me. And MAYBE if the broad looks OK, I say, ‘Go Baby.’ Or Maybe I say ‘Shove it, Bimbo.’ And before she can write word one I sue her.

“So don’t give me any First Amendment crapola, I got the Frank Amendment and mine is bigger than hers. Ring a ding ding.”

After a year of litigation that cost me over $100,000 in legal fees, Sinatra finally dropped his lawsuit, but by then he had sent his message to my publisher and the rest of the world that he did not want the book written. Many people were too frightened to speak on the record, and some actually feared for their lives, but over the course of three years I managed to interview 800 people, including members of Sinatra’s family, his mistresses, co-stars, friends, neighbors, employees, FBI agents, a few antagonists, and a couple of mobsters.

In 1986 His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra was published, and– despite his threats– I lived to see the book become number one on the New York Times best seller list and sell more than 1 million copies in hardback. All very gratifying, but best of all was receiving ASJA’s Outstanding Author Award that year for “courageous writing on popular culture.”

Publication of the Frank Sinatra biography was a triumph for all non-fiction writers who struggle against immense pressure to find their way to examine the public figures who influence our society.

Thirty years ago ASJA made it possible for me to find my way– and for that I am profoundly grateful. I accept your award for Career Achievement because YOU made my career all it has been– and I thank you from the bottom of my heart.

by Kitty Kelley

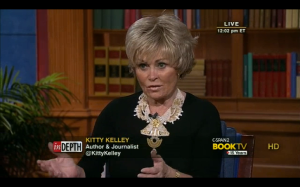

Kitty Kelley on Book-TV

Kitty Kelley appeared on C-Span2’s Book-TV “In Depth” program on Sunday, Nov. 3, 2013, answering questions from host Peter Slen and from viewers for three hours. The show may be viewed online here.

Ebooks Note

All seven bestselling biographies by Kitty Kelley are now available as ebooks.

Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star

His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra

Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography

Frank Sinatra and Me

by Kitty Kelley

I can’t say I wasn’t warned. Alarms started clanging the day I signed to write His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra (Bantam Books, 1986).

Some friends urged me to buy life insurance and make them the beneficiaries; others recommended bodyguards and a bullet-proof vest. The rumors of Frank Sinatra’s violence and his ties to organized crime were such that journalists joked in print about me ending up in concrete boots and sleeping with the fishes, if I proceeded to write his biography. Milton Berle joshed at the Friars Club, “Kitty Kelley wanted to be here tonight but an hour ago she tried to start her car.”

The laughs stopped when I received a message on my answering machine: “Soy-ving by Oy-ving here. Call ASAP ‘cuz we gotta soyve ya.”

I figured it was a New Jersey caterer who had the wrong number. Turns out it was a process server named Irving in the subpoena business of serving.

“Serving by Irving” was no joke. Frank Sinatra was suing me before I had written a word. In fact, the book was five years away from publication, but Sinatra wanted to make sure it would never be published. So he sued me (not my publisher) in Santa Monica, California, seeking $2 million in punitive damages, saying that he and he alone, or someone that he anointed could write his life story. Anyone else would have to pay $2 million dollars for daring to undertake the enterprise.

Getting sued by one of the most powerful men in the country—and one with mob connections—gets your attention. Fortunately, a national coalition of writers groups rose up to protest, claiming that Sinatra’s lawsuit against me was an assault upon all writers’ constitutionally protected freedoms of expression and should be dismissed on its face. In a joint statement they said: “The apparent goal behind Sinatra’s filing of this suit is to scare Ms. Kelley away from her investigation and, ultimately, to force her to scrap the book. Abuses of the judicial system such as these pose a serious threat to all writers.”

For one year, Sinatra pursued his lawsuit, but his allegations proved groundless, and he finally was forced to drop his case.

The writers groups applauded his action. “The court’s dismissal of this meritless suit—at the request of Mr. Sinatra—is a victory for all writers and the public,” stated their press release. “It reaffirms the right of the public to be informed about the lives of influential public persons whether or not they approve of the writer and his or her approach.”

The Baltimore Sun editorialized on the right to cover public figures without restriction: “If all the public can learn of the person is what the person himself wants it to learn, then our will become a very closed and ignorant society, unable to correct its ills, quite unlike what the drafters and subsequent generations of defenders of the free-speech First Amendment had in mind.”

I continued my work, interviewing Sinatra’s friends, employees, associates, former girl friends and lovers, federal law enforcement agents, plus musicians, movie stars and mobsters like Moe Dalitz, who had known and worked with him over the years. I also interviewed a few Sinatra relatives, including his son, Frank Sinatra, Jr. Through my years of research I received regular calls from Liz Smith, former New York Daily News gossip columnist, with all sorts of Sinatra stories, mostly scurrilous. Yet a few weeks before publication, Sinatra decided to make amends with the woman he demeaned on stage as “a dumpy, fat, ugly broad,” and referred to as “Lez” Smith. He invited her for drinks, she swooned, and Sinatra never had to read another negative word about himself in her columns.

My book was published in 1986 and enjoyed great success, selling over 1 million copies in hardback—a testament to the enduring fascination with Frank Sinatra. However, His Way was not applauded by the singer or his family, for the biography had opened doors that they had long kept locked.

Upon publication Nancy and Tina Sinatra called reporters to denounce the book and its author. Their father railed on television about “pimps and prostitutes” who write “a lot of crap” for money. “We nearly strangled on our pain and anger,” Nancy Sinatra said, reviling me as “the big C-word… I hate [Kitty Kelley]… If I ever met her, I don’t know what I’d do….” She ranted for months on her website and was still ranting years later when she tried to jump-start her career at the age of 54 by posing nude for Playboy. “Don’t ask me any questions about that goddamned Kitty Kelley or her goddamned book,” she warned reporters.

Tina Sinatra claimed that my biography had made her father ill, causing him to undergo major colon surgery in 1986 for seven and a half hours, and to endure a temporary colostomy. Tellingly, she waited until her father had died before she published her own book, which lacerated Barbara Sinatra, her father’s wife of 22 years, as a grasping, gold-digging wench not worthy of the family name. To this day the women speak only through lawyers.

Now that His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra is being published in trade paperback the alarms are once again clanging. “Take cover. Prepare for incoming,” warned one friend via e-mail. “Ole Blue Eyes might be gone but his daughters still prowl the forest.”

There is no longer any question about Frank Sinatra’s ties to the Mafia. As if to tease those mob connections, Nancy and Frank Sinatra, Jr. each appeared in different episodes of HBO’s The Sopranos. The producers of the hit series hung Frank Sinatra’s mug shot in Tony Soprano’s office at the Bada Bing. Yes, Ole Blue Eyes was once arrested on a morals charge and jailed for three days. (See pages 7-9 of His Way.) Movie directors continue to license his music as melodic striptease for their gangster films, and his picture inevitably appears in any film about the mafia.

My biography of Frank Sinatra is not paean to his music but rather an illumination of the man behind the music, who once described himself as “an 18-karat manic-depressive who lived a life of violent emotional contradictions with an over-acute capacity for sadness as well as happiness.”

Taking the man at his word I rode the roller coaster, and now a new generation of readers can join me for the ride.

Photo: Kitty Kelley interviewing Frank Sinatra Jr. on January 15, 1983 in his suite at the Hyatt Regency Washington in Washington DC for His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra.

Cross-posted from Huffington Post