Posts Tagged ‘James Baldwin’

Begin Again

By Kitty Kelley

Gird yourselves, white America: Eddie S. Glaude Jr. is putting you on notice, and he brought the receipts. The James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of African American Studies at Princeton prefaces his eighth book with praise quotes from several platinum authors who laud his brilliance and the genius of his subject on display in Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own.

Gird yourselves, white America: Eddie S. Glaude Jr. is putting you on notice, and he brought the receipts. The James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of African American Studies at Princeton prefaces his eighth book with praise quotes from several platinum authors who laud his brilliance and the genius of his subject on display in Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own.

To begin again on the subject of racism, Glaude proposes passing H.R. 40, a bill that would establish the Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African-Americans. It’s a suggestion that comes at the end of what the author himself describes in his introduction as “a strange book. It isn’t biography…it is not literary criticism…it is not straightforward history. Instead, Begin Again is some combination of all three in an effort to say something meaningful about our current times.”

Glaude starts gently but then lowers the boom. His book is a damning indictment of Donald Trump and white America, particularly white male America — or at least that part of it which believes in its superiority simply because it’s white.

Additionally, this book, provocative and lyrical in so many places, is Glaude’s personal journey through a tunnel of rage first explored by James Baldwin (1925-1987), whose writing — “close to seven thousand pages of work” — the professor has absorbed and studied and taught.

In Begin Again, Glaude challenges “the lie” that America is fundamentally good, that all men are created equal, and that the country is a beacon of light and a moral force in the world. “The stories we often tell ourselves of the civil rights movement and racial progress…[are] all too often lies,” he writes.

Instead, says the author, America is a racist nation that continues to tell the lie that it is a democracy while refusing to face the enduring legacy of slavery and ongoing systemic discrimination against African Americans.

With Baldwin as his guide, Glaude moves from the nonviolence practiced by Martin Luther King Jr. to the militancy of Huey P. Newton, Stokely Carmichael, and the Black Panther Party, the latter a “justifiable, even inevitable, response to white America’s betrayal of the civil rights movement.” Along the way, he lashes Richard Nixon’s “silent majority,” Reagan Democrats, and Trump voters for propagating “the lie.” Finally, Glaude concludes “that America is an identity that white people will protect at any cost.”

By 2016, he had become so disgusted by the Democratic Party for refusing to remedy Black suffering that he urged Black voters, many whose ancestors had paid with their lives for the right to vote, to abstain from voting for Hillary Clinton for president. His reasons seemed petty in the extreme:

“Much more was required than the Clinton name, or the endorsement of her bid for the presidency by President Obama, or by some celebrity, or the brandishing of hot sauce in [her] handbag.”

Choked by rage, he used his considerable influence to urge Black voters to leave the presidential ballot blank. Then the Republicans nominated Donald Trump. Still, Glaude refused to believe white America would elect “the carnival barker” to the highest office in the land.

Trimming his sails a bit, he co-authored an anemic essay in Time magazine with Fredrick Harris, a political scientist at Columbia, saying that if you were a Democrat in a battleground state like Wisconsin or Pennsylvania, you should vote for Hillary. But if you lived in a decidedly red state or an overwhelmingly blue one, you could blank out or vote your conscience.

Startlingly, the professor, who has studied Baldwin for 30 years, seems not to have learned from his mentor, especially on the value of presidential voting. In “Notes on the House of Bondage,” Baldwin ponders the 1980 presidential race between Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan:

“My vote will probably not get me a job or a home or help me through school or prevent another Vietnam or a third world war, but it may keep me here long enough for me to see, and use, the turning of the tide — for the tide has got to turn. And…if Carter is reelected, it will be by means of the black vote, and it will not be a vote for Carter. It will be a coldly calculated risk, a means of buying time.”

Surely, President Hillary Clinton would’ve bought Glaude more time than President Trump.

To his credit, Glaude admits his error. “I was wrong,” he writes, “and given my lifelong reading of Baldwin, it was an egregious mistake.”

Far less egregious, but still a mistake, was to publish this book without providing any photographs, especially since Glaude frequently refers to instances that demand illustration. For example, he writes about Sedat Pakay, a Turkish photographer who “offers a beautiful black-and-white portrait of Baldwin in the most intimate of settings.” No picture.

In another instance, Glaude refers to the opening of “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” a documentary of Baldwin’s time in the South during the Civil Rights movement, in which he sits “at a desk in his brother David’s apartment at 209 West Ninety-seventh Street, looking pensively at a book of photographs.” No picture. (Glaude writes pages about his own tour of the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, yet provides no pictures.)

He ends his book, appropriately, with a visit to Baldwin’s gravesite at Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York. Was it a simple marble stone, a granite slab, a large headstone marked with a quote? Or a family mausoleum to enfold Baldwin and his seven siblings? Sadly, there is again no picture. Glaude writes only that he knelt down, touched the earth, and quietly said, “Thank you.”

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

The March to the Dream

by Kitty Kelley

President Kennedy had to be pushed but after two bloody summers of Freedom Riders, television coverage of Bull Connors’ police dogs chewing children to bits, police men clubbing peaceful demonstrators and fire hoses slamming children against jagged brick buildings, leaving them torn and bleeding, JFK found his voice. He watched with disgust as Alabama Governor George Wallace, who had pledged “Segregation now. Segregation tomorrow. Segregation forever,” threatened to stand in the school house door to prevent two black students from integrating the state’s all-white university. That evening, June 11, 1963, John F. Kennedy ennobled his presidency with an address to the nation on equal rights:

President Kennedy had to be pushed but after two bloody summers of Freedom Riders, television coverage of Bull Connors’ police dogs chewing children to bits, police men clubbing peaceful demonstrators and fire hoses slamming children against jagged brick buildings, leaving them torn and bleeding, JFK found his voice. He watched with disgust as Alabama Governor George Wallace, who had pledged “Segregation now. Segregation tomorrow. Segregation forever,” threatened to stand in the school house door to prevent two black students from integrating the state’s all-white university. That evening, June 11, 1963, John F. Kennedy ennobled his presidency with an address to the nation on equal rights:

We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the Scriptures and as clear as the American Constitution…. If an American, because his skin is dark, cannot eat lunch in a restaurant open to the public, if he cannot send his children to the best schools available, if he cannot vote for the public officials who represent him…then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed? Who among us would then be content with counsels of patience and delay?

Next week I shall ask the Congress of the United States to make a commitment it has not fully made in this country to the proposition that race has no place in American life or law.

The President’s approval plummeted from 60 to 47 percent after his speech, and he and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, began counseling “patience and delay,” pleading with Civil Rights leaders to call off their scheduled March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Fearing violence and re-election in 1964, the administration said the March would do more harm than good. “We want success in Congress, not a big show at the Capital,” said the President.

The President’s approval plummeted from 60 to 47 percent after his speech, and he and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, began counseling “patience and delay,” pleading with Civil Rights leaders to call off their scheduled March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Fearing violence and re-election in 1964, the administration said the March would do more harm than good. “We want success in Congress, not a big show at the Capital,” said the President.

Kennedy summoned Civil Rights leaders to the White House to try to dissuade them but they remained resolute. The President relented and then called his brother: “Well, if we can’t stop them, we’ll run the damned thing.”

The March organizers agreed to demonstrate on a Wednesday so people would get back to their jobs and not stay the week-end. Parade permits were granted from 9 a.m to 5 p.m so that marchers would leave the city before dark. Schools, bars, restaurants and stores were closed. All elective surgeries in area hospitals were cancelled to free up 340 beds for riot-related emergencies.  The DC National Guard spent the summer training for riot duty and 2400 Guardsmen were sworn in as “special officers” with temporary arrest power. The city, including leaders like Mrs. Agnes E. Meyer, whose family owned The Washington Post and Newsweek, predicted “catastrophic outbreaks of violence, bloodshed and property damage.” The government closed the day of the March and federal employees were told to stay home.

The DC National Guard spent the summer training for riot duty and 2400 Guardsmen were sworn in as “special officers” with temporary arrest power. The city, including leaders like Mrs. Agnes E. Meyer, whose family owned The Washington Post and Newsweek, predicted “catastrophic outbreaks of violence, bloodshed and property damage.” The government closed the day of the March and federal employees were told to stay home.

The comedian Dick Gregory was amused by the fears of the white establishment. “I know the senators and congressmen are scared of what’s going to happen,” he said. “[But] I’ll tell you what’s going to happen. It’s going to be a great Sunday picnic.” To the Kennedy administration it looked like it was going to be a great big political fiasco.

Weeks in advance, the March, set for August 28, 1963, became global news as Civil Rights activists around the world announced that they, too, would march in Berlin, Munich, Amsterdam, London, Oslo, Madrid, The Hague, Tel Aviv, Cairo, Toronto, and Kingston, Jamaica.  Celebrities chartered planes from Hollywood’s progressive community, including Harry Belafonte, Paul Newman, Marlon Brando, Gregory Peck, Billy Eckstein, Lena Horne, Sidney Poitier, Sammy Davis, Jr., Tony Bennett, even Charleton Heston. Burt Lancaster flew from his movie location in Paris, and the dancer and jazz singer Josephine Baker arrived from France in her Free French uniform.

Celebrities chartered planes from Hollywood’s progressive community, including Harry Belafonte, Paul Newman, Marlon Brando, Gregory Peck, Billy Eckstein, Lena Horne, Sidney Poitier, Sammy Davis, Jr., Tony Bennett, even Charleton Heston. Burt Lancaster flew from his movie location in Paris, and the dancer and jazz singer Josephine Baker arrived from France in her Free French uniform.

Even with unprecedented police presence on the Mall, the President was so concerned about hot rhetoric stirring the crowds to violence that he positioned one of his advance men behind the sound system at the Lincoln Memorial ready to flip a special switch to cut the public address system, if necessary, and play a recording of Mahalia Jackson singing, “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.”

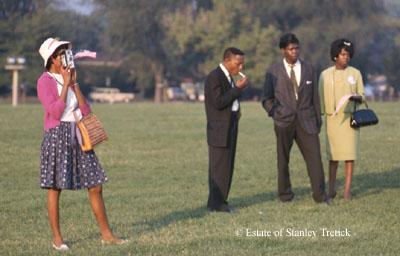

The day dawned with Washington’s usual summer swamp humidity but most of the 250,000 marchers arrived in their Sunday best. Women donned hats and high heels; men wore white shirts and ties. They dressed for church; their mission was religious—to heal sick hearts and open closed minds.

They marched and sang and swayed to the soaring sounds of the Freedom Singers and Odetta and Marian Anderson; they sat ten- deep at the Reflecting Pool, many dangling their feet in the water like pilgrims who once gathered at the Sea of Galilee.

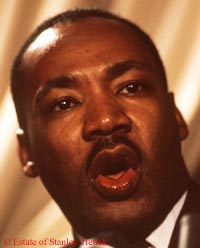

They cheered the speakers, and then they rose and roared in unison for the spell-binding finale of Martin Luther King, Jr., who had come to tell them about his dream for America “that one day the nation will rise up and live out the true meaning

of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’”

of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’”

The vast throng of humanity erupted into thunderous applause with each crescendo of Dr. King’s dream. In the rising cadence of a master spell-binder, he told America that if it was to become a great nation, it must make the dream of freedom come true for its black citizens. Even President Kennedy, watching on television, was transfixed. “He’s good. He’s damn good.”

The President had refused to participate in the March, but he invited the Civil Rights leaders to the White House at the end of the day. He greeted Dr. King by shaking his hand and saying, “I have a dream.”

Bubbling over with the success of the day which had occurred without one incident of violence, the President told reporters that he was edified by the speeches, the singing, the crowds—the entire event. “The nation can be properly proud of this march,” he said.

Photos from Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington, ©Estate of Stanley Tretick, used with permission.

Buy: Amazon Barnes & Noble Books-A-Million Apple IndieBound

Cross-posted from Huffington Post