Martin Luther King

John Lewis

by Kitty Kelley

A masterful biography is like a shooting star. It’s a celestial phenomenon that lights up the night sky and bestows a sense of wonder and excitement. Such a sensation occurs when the stars align and match a subject of worth with an estimable writer. That kind of luminous pairing occurs in David Greenberg’s John Lewis: A Life, the first major biography of the man Martin Luther King Jr. called “the boy from Troy.”

A masterful biography is like a shooting star. It’s a celestial phenomenon that lights up the night sky and bestows a sense of wonder and excitement. Such a sensation occurs when the stars align and match a subject of worth with an estimable writer. That kind of luminous pairing occurs in David Greenberg’s John Lewis: A Life, the first major biography of the man Martin Luther King Jr. called “the boy from Troy.”

Growing up as the third of 10 children in Alabama’s abysmal poverty, John Robert Lewis (1940-2020) aspired to be a preacher, a challenge for a child with a heavy rural accent and a speech impediment. At the age of 5, he practiced preaching to the chickens on his family’s farm in Pike County, on the outskirts of Troy. His elementary school education was at Dunn’s Chapel, built and funded by Julius Rosenwald, the Sears, Roebuck heir, who, with Booker T. Washington, created 5,000 schools for Black children around the South. After the Bible, Washington’s Up from Slavery became young John’s favorite book.

Born into segregation, Lewis sat in the “colored only” balcony to watch movies, and he drank Cokes standing outside the drugstore, while his white peers sat inside at the counter. He finally stopped going to the Pike County fair because he could only go on “colored day.”

Lewis became the first in his family to attend college. After being rejected by Troy University in 1957 due to segregation, he enrolled at American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, supposedly the “most liberal city” in the Confederacy. He later transferred to nearby Fisk University, where he earned his degree.

As a college sophomore, Lewis became transfixed by the preaching of nonviolence by King, Mahatma Gandhi, and members of the Social Gospel movement. Unshakeable in his faith that “God would never allow his children to be punished for doing the right thing,” the young man consecrated himself to the Civil Rights Movement and began organizing sit-ins at segregated lunch counters, stand-ins at segregated department stores, and swim-ins at segregated pools.

The youngest speaker at 1963’s March on Washington, Lewis was one of the original Freedom Riders to integrate seating on public buses; he was frequently bloodied and beaten unconscious. He was arrested and jailed dozens of times for demonstrating throughout the South, and once spent 40 days in the Mississippi State Penitentiary. Yet he never struck back, adhering always to Gandhi’s nonviolence creed. “We were determined not to let any act of violence keep us from our goal,” said the young man once so terrified of thunder and lightning that he’d hide in the family’s steamer trunk whenever it stormed.

Greenberg, a prize-winning professor of U.S. history and journalism at Rutgers, divides his spectacular biography of the Civil Rights icon into two parts: Protest (1940-1968) and Politics (1969-2020). One of his most arresting chapters, “John vs. Julian,” mimics Aesop’s fable of the tortoise and the hare: Lewis, the slow-moving tortoise, went up against Julian Bond, the fast-paced hare, in a 1986 campaign to be the Democratic candidate for Georgia’s 5th District seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. The campaign defined their professional futures while destroying their once-close friendship.

The contrast was stark: Lewis in shiny, rumpled suits and worn-out shoes, alongside Bond in custom-made blazers and tasseled loafers. Smooth, suave, and light-skinned, Bond, an “incorrigible ladies’ man,” was hiding a heavy cocaine habit, which Lewis exposed during a debate by challenging him to take a drug test. Bond refused.

Lewis pushed. “Can you tell us why you will not take the test,” he said, “so that people will know that you are not on drugs?”

Bond responded that he was not on drugs, and the moderator asked Lewis if he was accusing his opponent of illegal drug use.

“No,” said Lewis, a bit disingenuously. “I do not suspect that he is on drugs, I just feel like he should take the test to clear his name and remove public doubt. People need to know.”

Bond was incensed. “Why did I have to wait twenty-five years to find out what you really thought of me?”

Lewis replied, “Julian, my friend, this campaign is not a referendum on friendship. This is not a referendum on the past. This is a referendum on the future of our city, the future of our country.”

Supported by the white vote in Atlanta, Lewis won the run-off 52-48, and later, the election. “We will shake hands,” he told the press. “The wounds will heal.”

The wounds remained. Bond died in 2015 at age 75, and Lewis was not invited to the funeral.

The most compelling aspect of this work is its in-depth research, including 250 interviews, which has allowed Greenberg to paint a vivid portrait of the man heralded as “the conscience of congress.” The professor’s academic credentials (summa cum laude at Yale; a Ph.D. from Columbia), combined with his journalistic talent (he has bylines in Politico, the New Yorker, the Atlantic, and the New York Times), have brought forth this captivating biography of a hero who cried easily, laughed often, and never lost faith in “the beloved community,” where all God’s children, particularly those who got into “good trouble,” would be blessed.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

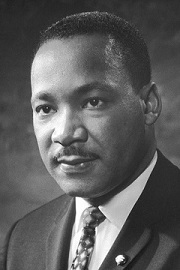

King: A Life

by Kitty Kelley

They said one to another

Behold here cometh the Dreamer

Let us slay him

And we shall see what will become of his dreams.

– Genesis 37:19-20

These words are carved into the cement plaque that rests outside room 306 of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. They mark the place where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. The dreamer’s death transformed his murder site into a shrine that now houses the National Civil Rights Museum, where King’s life continues to inspire, drawing thousands of visitors every year.

These words are carved into the cement plaque that rests outside room 306 of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. They mark the place where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. The dreamer’s death transformed his murder site into a shrine that now houses the National Civil Rights Museum, where King’s life continues to inspire, drawing thousands of visitors every year.

Scholars and historians have long explored the legacy of the Baptist minister from Georgia who preached a gospel of nonviolence. Deservedly, many King biographies have won prestigious prizes, among them Taylor Branch’s magisterial trilogy: Parting the Waters, Pillar of Fire, and At Canaan’s Edge. Additional tributes to King include I May Not Get There with You by Michael Eric Dyson; Bearing the Cross by David J. Garrow; Let the Trumpet Sound by Stephen B. Oates; Death of a King by Tavis Smiley; The Promise and the Dream by David Margolick; and The Sword and the Shield by Peniel E. Joseph.

Now comes Jonathan Eig with King: A Life, which promises “to recover the real man from the gray mist of hagiography.” Regrettably, says the author, “In the process of canonizing King, we’ve defanged him…[but] King was a man, not a saint, not a symbol.” In removing the mantle, Eig presents here an orator of soaring rhetoric who unapologetically plagiarized his speeches, saying his goal was to move audiences. Even King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech seems to have had its origins in Langston Hughes’ poems “I Dream a World” and “Dream Deferred.”

Misappropriating others’ work is a grievous sin for scholars, a “bad habit,” Eig writes, that King started in high school and continued as a graduate student at Crozier and later at Boston University, where he earned his Ph.D. with a dissertation that contained more than 50 sentences lifted from someone else’s work. By contrast, readers will note how generous Eig is to his own sources, giving previous biographers their due and quoting many by name in his text, not simply relegating them to chapter notes in the back of the book. Just as noteworthy is Eig’s appreciation for all who contributed to King: A Life; he lists each name under “Acknowledgements: Beloved Community.”

In this biography, his sixth book, Eig writes like an Olympic diver who jackknifes off the high board, slicing the water without a ripple. He performs with sheer artistry, like Picasso paints and Astaire dances. In unspooling the life of King, Eig presents a complicated man who attempted suicide twice; who was plagued by clinical depression so deep it required hospitalization; who chewed his nails; and who gave up the “true love” of his life, a white woman named Betty Moitz, because he realized, with her, he would never be accepted as a preacher in Black churches. The late Harry Belafonte, who himself married a white woman, told Eig that King never stopped talking about Moitz, and King’s mentor in graduate school described him after the break-up as “a man with a broken heart,” adding, “he never recovered.”

Although he married Coretta Scott and had four children with her, King pursued many women throughout his life. While Eig is unsparing about those extramarital affairs, he writes gently: “King’s busy schedule of travel also afforded him opportunities to spend time with women other than Coretta.”

The author also draws interesting similarities between King and John F. Kennedy, both of whom indelibly marked their era:

- Both were influenced by powerful (and philandering) fathers.

- Both enjoyed a privileged lifestyle above their contemporaries.

- Both were accused of plagiarism.

- Both experienced discrimination (JFK as an Irish Catholic; King as a Black man).

- Both excelled as public speakers.

- Both were assassinated.

King was particularly threatened by the never-made-public tape recordings FBI director J. Edgar Hoover ordered, turning federal agents into bloodhounds and instructing them to install bugs wherever King traveled. Hoover distributed copies of the recordings, which contained evidence of “unnatural sexual acts,” to President Lyndon Johnson, White House officials, and journalists in order to undermine King’s credibility. To further ensure his ruin, Hoover met with a group of woman journalists and declared King the country’s “most notorious liar.”

King reportedly wept over the slur to his life’s work but managed a masterful response to the press:

“I cannot conceive of Mr. Hoover making a statement like this without being under extreme pressure. He has apparently faltered under the awesome burden, complexities and responsibilities of his office. Therefore, I cannot engage in a public debate with him. I have nothing but sympathy for this man who has served his country well.”

By opposing the “immoral” war in Vietnam, King, who’d received the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, drew the unremitting ire of Johnson. As Eig writes, King’s “conscience would not allow him to cooperate with an advocate and purveyor of war.” Infuriated, Johnson never forgave the man who’d given his presidency its three greatest legislative achievements: the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

While Eig reveals the flawed man behind the myth, Martin Luther King Jr. still stands tall and strong enough to shoulder Shakespeare’s words from “Measure for Measure”:

They say best men are molded out of faults,

And, for the most, become much more the better

For being a little bad

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

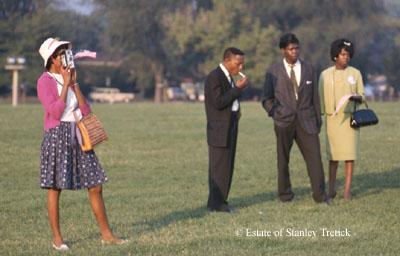

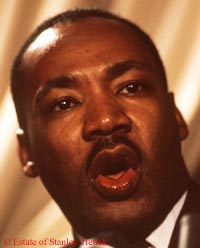

(Color photo of Martin Luther King Jr. by Stanley Tretick, 1966, from Let Freedom Ring.)

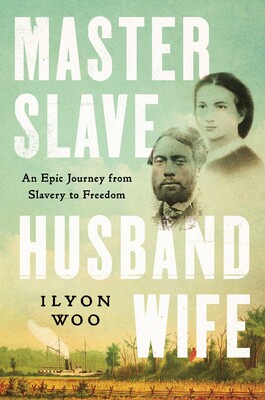

Master Slave Husband Wife

by Kitty Kelley

The morning after Martin Luther King Day 2023 marked the release of Ilyon Woo’s extraordinary Master Slave Husband Wife: An Epic Journey from Slavery to Freedom. Reviewers received advance proofs from the publisher with a note from Bob Bender, executive editor of Simon & Schuster, extolling the book and wondering why the story of Ellen and William Craft was not yet a staple of American history.

The morning after Martin Luther King Day 2023 marked the release of Ilyon Woo’s extraordinary Master Slave Husband Wife: An Epic Journey from Slavery to Freedom. Reviewers received advance proofs from the publisher with a note from Bob Bender, executive editor of Simon & Schuster, extolling the book and wondering why the story of Ellen and William Craft was not yet a staple of American history.

Soon, Mr. Bender. Soon.

The Crafts’ story is no ordinary slave narrative, although “ordinary” hardly describes the harrowing attempts that desperate human beings made in 18th- and 19th-century America to flee slavery’s choke-hold. Hordes of bounty hunters laid in wait to capture fugitives and drag them back to their owners in chains. Few made it to freedom, which is why the Crafts are so extraordinary: They took white supremacy and turned it upside down and sideways in order to escape in plain sight, executing one of the boldest feats of self-emancipation in U.S. history.

Ellen Craft was born to a white father, James Smith, who also enslaved Ellen’s 18-year-old mother. Smith’s wife gave Ellen — a living, daily reminder of her husband’s infidelity — as a wedding present to their daughter, Eliza, when she married Robert Collins of Macon, Georgia. Being half-sisters, the girls had grown up together, and Ellen, looking as white as Eliza, was trusted as a “house slave” to sew and cook and take care of the children. While in Macon, Ellen fell in love with William Craft, an enslaved man who lived nearby. Together, they schemed to run away at the end of 1848, more than a decade before the Civil War.

They plot every detail of their escape with strategic precision. Ellen, an expert seamstress, begins sewing the costume she will wear to disguise herself as a white man in failing health traveling to Philadelphia for medical treatment, accompanied by “his” slave. She makes baggy plus-fours — the stylish men’s trousers of the day — a white silk shirt, a black cravat, and a custom-designed jacket that only a gentleman of means could afford. Traveling as “Mr. Johnson,” she wears dark green glasses and a “double-story” black silk hat “befitting how high it rises, and the fiction it covers.”

She applies poultices to her face and wraps her right hand in bandages and a sling to explain why she can’t sign travel documents at several stops. (Being enslaved, Ellen was not allowed to learn how to read or write.) The dark-skinned William, acting like an obsequious slave, helps Ellen on and off trains and buses and boats, attending to “his” every need during their journey. At each stop, William ushers his infirm “master” to “his” first-class cabin before retiring to the colored quarters, where he eats from a slop bowl and sleeps standing up.

From Macon, the train rolls into Savannah, “City of Shade and Silence,” and site of the largest slave market in America, known as “the Weeping Time.” With staggering audaciousness, master and slave continue by steamship to Charleston, South Carolina, where, Woo writes:

“All along the harbor were tall ships and steamers, weighing the waves with their cargo; golden crops of rice, bales of cotton, chinoiserie — and chained below decks, the enslaved, a major commodity in this international port. There were slave sales near the docks, in shops, closer inland, and by the Custom House, which hosted the city’s largest open-air slave market on its north side, as Ellen knew. The sight was so disturbing to foreigners (and therefore bad for business) that, in a few years, the city would pass laws to hustle the trade indoors.”

Days later, the Crafts arrive in Richmond, Virginia, a veritable police state since Nat Turner’s Rebellion in 1831, still considered the most significant slave uprising in American history. “Mr. Johnson” and “his” slave rumble over Aquia Creek to Washington, DC, and through a dark channel to Fort McHenry in Baltimore, where Francis Scott Key, himself an enslaver, wrote “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Three more stops, and the couple finally cross the Mason-Dixon Line and reach Philadelphia, the so-called City of Brotherly Love, where even the Quakers drew lines to separate the “colored” benches in their meetinghouses.

Master Slave Husband Wife hits all the marks of a masterpiece: unforgettable characters, stirring conflicts, breathtaking courage, and a pulsating plot wrapped around an unforgiveable sin. Author Woo is a rare breed of writer — a scholar with a Ph.D. who’s nevertheless mastered the art of narrative nonfiction. She tells this story with incomparable skill, following the Crafts from Philadelphia to Boston, where they become icons of the abolitionist movement, traveling the antislavery lecture circuit. But the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 forces them to keep on the run. By law, they’re still enslaved and deeply in danger, especially once Robert Collins, Ellen’s owner back in Georgia, hires bounty hunters to track them down.

No longer safe in the U.S., the Crafts move to England for several years, where they bring up six children and publish an account of their escape, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom. When Abraham Lincoln signs the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, the Crafts feel safe enough to return home, first to South Carolina and then to Georgia, where they start a school and live out the remainder of their days.

Ellen and William Craft embody the human drive to relentlessly pursue freedom. Ilyon Woo, in Master Slave Husband Wife, honors their story with grace and humanity, and presents her publisher with a phenomenon.

Stand by, Mr. Bender. Stand by.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

A Trail of Tears and Triumph

by Kitty Kelley

“April is the cruelest month,” wrote the poet T.S. Eliot, and for followers of Martin Luther King Jr., April 4, 1968, was the cruelest day. At 6:01 p.m. on that Thursday, the beloved preacher of nonviolence was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee.

“April is the cruelest month,” wrote the poet T.S. Eliot, and for followers of Martin Luther King Jr., April 4, 1968, was the cruelest day. At 6:01 p.m. on that Thursday, the beloved preacher of nonviolence was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee.

Hours later, riots erupted throughout the country as angry mobs smashed windows, trashed stores, and blew up cars, leaving dozens dead and more than 100 cities smoldering. President Lyndon Johnson finally summoned the National Guard to restore order.

More than five decades later, some scars remain, but Dr. King’s dream of a beloved community still shines, even in the poorest pockets of the country. I recently joined Stanford University’s “Following King: Atlanta to Memphis” tour, led by Professor Clayborne Carson, senior editor of The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Vols. I-VII. Traveling by bus for a week — masked, in the era of covid — we patronized only minority-owned hotels and restaurants.

We began in Atlanta with a visit to Dr. King’s last home, the one he purchased after winning the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize. We toured the National Center for Civil and Human Rights and learned from a freshman at Morehouse College why he values his education on the 61-acre campus of one of America’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU), which is close to Spelman College, an HBCU for women:

“We both fall under the umbrella of Atlanta University Center, so we can attend classes on either campus…Our slogan here at Morehouse is ‘Let There be Light,’ and while it’s prevalent in my generation [Class of 2025] not to speak your mind lest you be canceled, here, people are not making fun of you or out to cancel you. They tell us: ‘Say your ignorance in class so you don’t say it in the world.’”

Before leaving Atlanta, we visit the Ebenezer Baptist Church, the spiritual home of Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, where the Rev. Raphael G. Warnock now serves every Sunday as pastor. The rest of the week, he serves as Georgia’s junior senator in the U.S. Senate.

Boarding the bus, we headed for Montgomery, Alabama, home of the Confederacy, where we visit the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, created by Bryan Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), the nonprofit that guarantees the defense of any prisoner in Alabama sentenced to death. For many of us, this is the most upsetting museum on the tour because it forces you to see the terrible connection between 1865 and today.

The EJI has identified more than 4,000 Black men, women, and children who were lynched. At the site’s center hang 800 rusted steel monuments, one for each county in the U.S. where documented lynchings took place. Entering the museum, we were confronted with replicas of slave pens, where we saw and heard first-person accounts from enslaved people describing what it was like to be ripped from their families and await sale at the nearby auction block. We learned what “sold down the river” means: Many enslaved people were punished with a transfer from the North to harsher conditions in the South. Etched in bronze is Harriet Tubman’s quote, “Slavery is the next thing to hell.”

On a nearby street corner, we meet the artist Michelle Browder, who showed us her outdoor gallery honoring “Mothers of Gynecology”; her 15-foot-high sculptures depict three enslaved women subjected to brutal experiments for “supposed” medical advancement.

From Montgomery, we were bused to Birmingham (aka “Bombingham”) and the 16th Street Baptist Church, where four little girls were killed by a bomb as they prepared to sing in their choir on September 15, 1963. The pastor’s undelivered sermon that Sunday was entitled “A Love that Forgives.”

Weeks before, 300,000 people had gathered peacefully on the National Mall in Washington, DC, to hear Dr. King’s soaring “I Have a Dream” speech. Later, he was jailed in Alabama. While there, he wrote his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail” on scraps of paper and bits of toilet tissue that his lawyer smuggled out piece by piece on each visit. Dr. King’s message berated white moderates “devoted to order, not to justice,” particularly those white church leaders “more cautious than courageous.”

From Montgomery, we traveled to Selma to meet our no-nonsense guide in the projects. “We’re in the ‘hood now, so if you hear a pop-pop, duck,” she said. People on the bus squirmed as she delivered her blunt commentary:

“Selma is a city of barely 20,000, and 80 percent of us are African American, still living in the poorest wards…Voting registration has shrunk because folks ask, ‘What’s voting done for us?’ We’re a broken economy, a broken community…Hate groups study us as a failed model of Democratic policies.”

Rain fell as we walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, named for a Confederate general and Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan and the site of “Bloody Sunday,” March 7, 1965, when police attacked Civil Rights marchers with horses, clubs, and tear gas.

We later stopped in Meridian and Jackson, Mississippi, enroute to Memphis, where we visited the Lorraine Motel, with its white plastic wreath of blood red roses marking the spot on the second-floor balcony where Dr. King was assassinated. The plaque beneath reads:

“They said one to another,

Behold, here cometh the dreamer,

Let us slay him

And we shall see what will become of his dream.”

– Genesis 37.19-20

The motel site has been expanded into a complex of buildings incorporated as the National Civil Rights Museum in 1991, the first in the U.S. dedicated to telling the Black Civil Rights story. It’s also been called “The Conspiracy Museum” because its second floor, entitled “Lingering Questions,” chronicles the capture and arrest of James Earl Ray and explores myriad conjectures about whether Dr. King’s killer acted alone.

Outside on the street, a tiny woman named Jacqueline Smith protests the $27 million museum complex. She weighs no more than 90 pounds, but her outrage is ferocious. She’s been standing on the corner every day since 1988, when she was evicted from the motel to make way for the museum’s construction.

“What’s the point of all this?” she asks. “What does this rich museum offer the needy, the homeless, the poor, the hungry, the displaced, and the disadvantaged? Dr. King said: ‘Spend the necessary money to get rid of slums, eradicate poverty.’ This museum was built with non-unionized labor. Dr. King was all for unionized workers. This museum celebrates his murderer… does the John F. Kennedy Library celebrate Lee Harvey Oswald?”

Someone starts to speak, but Jackie brooks no interruption. “Why don’t you white people do what’s right for a change?”

Quietly, we return to our bus, edified by Dr. King’s vocal disciple.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

“Martin’s Dream Day” Chosen for ILA Teachers’ Choices Reading List

The International Literacy Association (ILA) on May 1, 2018 announced the winning titles of the 2018 Choices reading lists: an annual selection of outstanding new children’s and young adults’ books, curated by students and educators themselves. These lists are issued during Children’s Book Week each year.

The International Literacy Association (ILA) on May 1, 2018 announced the winning titles of the 2018 Choices reading lists: an annual selection of outstanding new children’s and young adults’ books, curated by students and educators themselves. These lists are issued during Children’s Book Week each year.

This year, Martin’s Dream Day by Kitty Kelley was included as a Teachers’ Choice for Intermediate Readers (ages 8-11).

Each year, thousands of children, young adults, and educators around the United States select their favorite recently published books for the International Literacy Association’s Choices reading lists. These lists are used in classrooms, libraries, and homes to help readers of all ages find books they will enjoy.

The International Literacy Association (ILA) is a global advocacy and membership organization dedicated to advancing literacy for all through its network of more than 300,000 literacy educators, researchers and experts across 78 countries. With over 60 years of experience, ILA has set the standard for how literacy is defined, taught and evaluated. ILA collaborates with partners across the world to develop, gather and disseminate high-quality resources, best practices and cutting-edge research to empower educators, inspire students and inform policymakers. ILA publishes The Reading Teacher, Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy and Reading Research Quarterly.

The International Literacy Association (ILA) is a global advocacy and membership organization dedicated to advancing literacy for all through its network of more than 300,000 literacy educators, researchers and experts across 78 countries. With over 60 years of experience, ILA has set the standard for how literacy is defined, taught and evaluated. ILA collaborates with partners across the world to develop, gather and disseminate high-quality resources, best practices and cutting-edge research to empower educators, inspire students and inform policymakers. ILA publishes The Reading Teacher, Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy and Reading Research Quarterly.

“Martin’s Dream Day” is Woodson Honor Winner

National Council for the Social Studies “established the Carter G. Woodson Book Awards for the most distinguished books appropriate for young readers that depict ethnicity in the United States. First presented in 1974, this award is intended to ‘encourage the writing, publishing, and dissemination of outstanding social studies books for young readers that treat topics related to ethnic minorities and race relations sensitively and accurately.’”

2018

Elementary Level Honoree

Martin’s Dream Day

by Kitty Kelley

Atheneum Books for Young Readers

Kitty Kelley Publishes Her First Children’s Book

Kitty Kelley’s first book for children will be published January 3, 2017 by Atheneum Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing. Martin’s Dream Day tells the story of the 1963 March on Washington, illustrated by Stanley Tretick’s photography.

“Martin Luther King dreamed of making justice a reality for all God’s children so it seemed right to share the images of his dream day with children,” said Kelley.

Ages 5 and up.

Read press release here.

Kitty Kelley will donate her proceeds from this book to Reading Is Fundamental, the largest nonprofit children’s literacy organization in the United States.

Buy in hardcover or in ebook format.

Coalition to Stop Gun Violence

Kitty Kelley spoke on December 8, 2014 at the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence 4oth Anniversary Celebration in Washington D.C.:

Kitty Kelley spoke on December 8, 2014 at the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence 4oth Anniversary Celebration in Washington D.C.:

This is an evening I’ve been looking forward to because it gives me a chance to be in a room with people I consider royalty who are enlightened and represent a sense of values that I have long admired. So I come here tonight to pay tribute to each of you for your commitment to stop gun violence.

I salute you because you have refused to be defeated by huge odds. You have not become disillusioned by the political failure in this country to legislate gun control; you have not been intimidated by the N.R.A. You have stood tall and you have not wavered. You are clear-eyed about the obstacles but you focus on your high purpose, which is to bring us back to our humanity. And in the words of that old spiritual sung by those who marched for Civil Rights–you shall not be moved.

Everything about this organization underscores humanity. You named yourself a “coalition” which by its very definition embraces outreach to others–of different religions, different regions, different races. Your roots spring from the hopeful days of the Civil Rights movement for justice and equality. To date your organization covers 47 different organizations which share your mission of non-violence. One purpose, many people.

When President Kennedy addressed the nation on Civil Rights in 1962, he said, “This is not a legal or legislative issue alone. We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the scriptures and as clear as the American constitution.”

But old as it might be and clear as it might seem, it sometimes looks impossible to achieve. Yet Martin Luther King, Jr., never lost hope. He told us that “the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice.” He said that arc would lead us to a place of peace for all humanity. He called the place the Beloved Community.

And tonight I feel like I am in the middle of that Beloved Community because for 40 years you have given your time, your talent and your treasure to stop gun violence. You have held faith in the worst of times even as we are still reeling from Ferguson, Missouri, and Trayvon Martin and too many school shootings to recount.

Some days it’s hard to believe that the arc of the moral universe is ever going to bend, but this Coalition keeps us on course, and remind us in the words of Abraham Lincoln that “To sin by silence makes cowards of men.” This Coalition helps us all be brave, to stand up, to speak out, and to not be moved.

Your mission is more than an act of faith, or a statement of hope in a noble cause. It’s a real vow, a pledge of allegiance, and a promise to help us reclaim our humanity and to live in a civilized world.

So you have great reason to celebrate tonight and on the occasion of your 40th anniversary I salute each one of you–and none more so than your founder, Mike Beard, the man who brought us together. Mike marched with Martin Luther King and he worked for John F. Kennedy. He saw in both men the best hopes for America, and when both were struck down by gun violence, Mike found his cause and this Coalition. For those of us who never marched with Dr. King and never knew President Kennedy, Mike has bound us to their legacies, and for that we owe him our deepest thanks.

Kitty Kelley donated copies of Let Freedom Ring for those attending the Celebration, with a letter from her enclosed:

Kitty Kelley on Book-TV

Kitty Kelley appeared on C-Span2’s Book-TV “In Depth” program on Sunday, Nov. 3, 2013, answering questions from host Peter Slen and from viewers for three hours. The show may be viewed online here.

The March to the Dream

by Kitty Kelley

President Kennedy had to be pushed but after two bloody summers of Freedom Riders, television coverage of Bull Connors’ police dogs chewing children to bits, police men clubbing peaceful demonstrators and fire hoses slamming children against jagged brick buildings, leaving them torn and bleeding, JFK found his voice. He watched with disgust as Alabama Governor George Wallace, who had pledged “Segregation now. Segregation tomorrow. Segregation forever,” threatened to stand in the school house door to prevent two black students from integrating the state’s all-white university. That evening, June 11, 1963, John F. Kennedy ennobled his presidency with an address to the nation on equal rights:

President Kennedy had to be pushed but after two bloody summers of Freedom Riders, television coverage of Bull Connors’ police dogs chewing children to bits, police men clubbing peaceful demonstrators and fire hoses slamming children against jagged brick buildings, leaving them torn and bleeding, JFK found his voice. He watched with disgust as Alabama Governor George Wallace, who had pledged “Segregation now. Segregation tomorrow. Segregation forever,” threatened to stand in the school house door to prevent two black students from integrating the state’s all-white university. That evening, June 11, 1963, John F. Kennedy ennobled his presidency with an address to the nation on equal rights:

We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the Scriptures and as clear as the American Constitution…. If an American, because his skin is dark, cannot eat lunch in a restaurant open to the public, if he cannot send his children to the best schools available, if he cannot vote for the public officials who represent him…then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed? Who among us would then be content with counsels of patience and delay?

Next week I shall ask the Congress of the United States to make a commitment it has not fully made in this country to the proposition that race has no place in American life or law.

The President’s approval plummeted from 60 to 47 percent after his speech, and he and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, began counseling “patience and delay,” pleading with Civil Rights leaders to call off their scheduled March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Fearing violence and re-election in 1964, the administration said the March would do more harm than good. “We want success in Congress, not a big show at the Capital,” said the President.

The President’s approval plummeted from 60 to 47 percent after his speech, and he and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, began counseling “patience and delay,” pleading with Civil Rights leaders to call off their scheduled March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Fearing violence and re-election in 1964, the administration said the March would do more harm than good. “We want success in Congress, not a big show at the Capital,” said the President.

Kennedy summoned Civil Rights leaders to the White House to try to dissuade them but they remained resolute. The President relented and then called his brother: “Well, if we can’t stop them, we’ll run the damned thing.”

The March organizers agreed to demonstrate on a Wednesday so people would get back to their jobs and not stay the week-end. Parade permits were granted from 9 a.m to 5 p.m so that marchers would leave the city before dark. Schools, bars, restaurants and stores were closed. All elective surgeries in area hospitals were cancelled to free up 340 beds for riot-related emergencies.  The DC National Guard spent the summer training for riot duty and 2400 Guardsmen were sworn in as “special officers” with temporary arrest power. The city, including leaders like Mrs. Agnes E. Meyer, whose family owned The Washington Post and Newsweek, predicted “catastrophic outbreaks of violence, bloodshed and property damage.” The government closed the day of the March and federal employees were told to stay home.

The DC National Guard spent the summer training for riot duty and 2400 Guardsmen were sworn in as “special officers” with temporary arrest power. The city, including leaders like Mrs. Agnes E. Meyer, whose family owned The Washington Post and Newsweek, predicted “catastrophic outbreaks of violence, bloodshed and property damage.” The government closed the day of the March and federal employees were told to stay home.

The comedian Dick Gregory was amused by the fears of the white establishment. “I know the senators and congressmen are scared of what’s going to happen,” he said. “[But] I’ll tell you what’s going to happen. It’s going to be a great Sunday picnic.” To the Kennedy administration it looked like it was going to be a great big political fiasco.

Weeks in advance, the March, set for August 28, 1963, became global news as Civil Rights activists around the world announced that they, too, would march in Berlin, Munich, Amsterdam, London, Oslo, Madrid, The Hague, Tel Aviv, Cairo, Toronto, and Kingston, Jamaica.  Celebrities chartered planes from Hollywood’s progressive community, including Harry Belafonte, Paul Newman, Marlon Brando, Gregory Peck, Billy Eckstein, Lena Horne, Sidney Poitier, Sammy Davis, Jr., Tony Bennett, even Charleton Heston. Burt Lancaster flew from his movie location in Paris, and the dancer and jazz singer Josephine Baker arrived from France in her Free French uniform.

Celebrities chartered planes from Hollywood’s progressive community, including Harry Belafonte, Paul Newman, Marlon Brando, Gregory Peck, Billy Eckstein, Lena Horne, Sidney Poitier, Sammy Davis, Jr., Tony Bennett, even Charleton Heston. Burt Lancaster flew from his movie location in Paris, and the dancer and jazz singer Josephine Baker arrived from France in her Free French uniform.

Even with unprecedented police presence on the Mall, the President was so concerned about hot rhetoric stirring the crowds to violence that he positioned one of his advance men behind the sound system at the Lincoln Memorial ready to flip a special switch to cut the public address system, if necessary, and play a recording of Mahalia Jackson singing, “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.”

The day dawned with Washington’s usual summer swamp humidity but most of the 250,000 marchers arrived in their Sunday best. Women donned hats and high heels; men wore white shirts and ties. They dressed for church; their mission was religious—to heal sick hearts and open closed minds.

They marched and sang and swayed to the soaring sounds of the Freedom Singers and Odetta and Marian Anderson; they sat ten- deep at the Reflecting Pool, many dangling their feet in the water like pilgrims who once gathered at the Sea of Galilee.

They cheered the speakers, and then they rose and roared in unison for the spell-binding finale of Martin Luther King, Jr., who had come to tell them about his dream for America “that one day the nation will rise up and live out the true meaning

of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’”

of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’”

The vast throng of humanity erupted into thunderous applause with each crescendo of Dr. King’s dream. In the rising cadence of a master spell-binder, he told America that if it was to become a great nation, it must make the dream of freedom come true for its black citizens. Even President Kennedy, watching on television, was transfixed. “He’s good. He’s damn good.”

The President had refused to participate in the March, but he invited the Civil Rights leaders to the White House at the end of the day. He greeted Dr. King by shaking his hand and saying, “I have a dream.”

Bubbling over with the success of the day which had occurred without one incident of violence, the President told reporters that he was edified by the speeches, the singing, the crowds—the entire event. “The nation can be properly proud of this march,” he said.

Photos from Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington, ©Estate of Stanley Tretick, used with permission.

Buy: Amazon Barnes & Noble Books-A-Million Apple IndieBound

Cross-posted from Huffington Post