His Way

BIO Award Winner Kitty Kelley’s Speech

Kitty Kelley won the 2023 Biographers International Organization Award. On Saturday, May 20, at the 2023 BIO Conference, it was also announced that Kelley will make a gift of $1 million to BIO, to be given over the course of five years. You can read more about that here.

The following is Kitty’s keynote address:

If I get run over tonight, please make sure that this BIO award leads my obit, because it’ll be the only time that my name shares the same space with Ron Chernow and Robert Caro and Stacy Schiff. But I don’t want to think about obituaries right now. I want to share with you a little bit about the writing life that brings me here today.

I love books and as much as I enjoy fiction, I bend my knee to nonfiction, particularly biography—the art of telling a life story. All kinds of life stories—memoir, authorized and unauthorized biography, historical narrative, or contemporary profiles.

In the last few decades, I’ve written biographies about living icons, a genre that is sometimes dismissed as “unauthorized biography” and, unfortunately, the term is sometimes said as if you’re emptying a bedpan or cleaning up the dog’s mess. Unauthorized biographies are not approved by everyone and rarely appreciated by their subjects. One exception, of course, is the New Testament, which was written by disciples who never knew their subject.

About 40 years ago, I thought I’d died and gone to biography heaven when Bantam Books offered me a grand advance to write the unauthorized biography of Frank Sinatra. I’d written two previous biographies and been robbed on both. On the first one, I didn’t have an agent—which is like driving a car without a steering wheel. On the second, I had an agent straight out of Oliver Twist. You may remember the woman who advised Linda Tripp to advise Monica Lewinsky to save her blue dress. Well, that same woman was once a literary agent who caused about $70,000 in foreign sales to go missing on my Elizabeth Taylor biography. My lawyer was incensed and insisted I sue. I told him to write the agent, say I’d misplaced records, and ask for another accounting. I figured that way she could correct herself and repay the missing monies.

I’m embarrassed to admit that I let this go on for over a year because I just couldn’t believe a literary agent would steal from a client. My lawyer said, “Try to get it into your fat head: She’s not Max Perkins. She’s Ma Barker.”

After 17 months, I finally filed suit. Depositions were taken and the case went to federal court in Washington, D.C. I fully expected her to settle because the evidence was so overwhelming. Instead, the case went to trial and the jury found Ma Barker guilty on all six counts, including fraud. They demanded she make payment on the courthouse steps and even asked for punitive damages.

I suppose the lawsuit was a great victory, because I unloaded a bad agent and got a good one, but I was in no hurry to do another biography. I’d just learned the hard way that there’s no education in the second kick of a mule. I’d undertaken the Elizabeth Taylor biography, hoping to write about the Hollywood studio system that had shaped our fantasies for most of the 20th century. I envisioned weaving that theme into the life story of Elizabeth Taylor, who grew up as a little girl at MGM, and went to school at MGM and . . . married many MGM men. But my plan for this historical narrative soon got buried in Ms. Taylor’s Technicolor life of husbands and hospitals and jewelry stores.

My agent asked, if I were to consider writing another life story, who would be of interest? I said, “Well, the gold ring on the merry-go-round would be Frank Sinatra, because no one’s really done it, and he epitomizes the American dream.” She agreed and that was the end of the subject until a couple weeks later when she called and said she had a generous offer from Bantam Books.

Soon I was back in the biography business, thinking I’d paid my hard luck dues. I’d had a bandit publisher on my first book and a thieving agent on my second. Now was third time lucky. And for a few weeks it was . . . until I was served a subpoena from Frank Sinatra, announcing that he was suing me for $2 million dollars for usurping the rights to his life story. He claimed that he and he alone (or someone he authorized) was entitled to write his life story, and I certainly had not been authorized.

I immediately called my publisher, and Bantam’s legal counsel informed me that I was on my own. “Mr. Sinatra has not sued us,” she said. “He’s sued you, and since you’ve not given us a manuscript, we’re not involved. So, I’d advise you to get legal counsel in California, which is where you’ve been sued and do keep us informed.”

“But I haven’t written a word. I’ve only just begun. My manuscript is years away.”

“We’ll talk then,” she said, before hanging up.

Now, getting sued by a billionaire with Mafia ties concentrates the mind, especially after your publisher leaves the scene. I called my friend, the president of Washington Independent Writers, to commiserate. “I wish we could help you, Kitty, but we’re almost broke,” she said. I assured her that I wasn’t looking for money—just moral support. “Well, in that case, let me get on the horn.” She contacted several writers’ groups, including the Authors Guild and PEN and the American Society of Journalists and Authors, and Sigma Delta Chi, and the National Writers Union. Days later, they held a press conference at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., to denounce Sinatra for using his power and influence to intimidate a writer before she’d written a word. They denounced his lawsuit and his assault on the First Amendment. As journalists, they understood what was at stake if Sinatra prevailed.

I retained the law firm of O’Melveny and Myers in Los Angeles and tried to keep working on the book, but was interrupted a few weeks later when I was in New York doing interviews and my lawyer called to tell me to get back to D.C. because the LA lawyers were coming to Washington for a meeting that would also be attended by my publisher. The LA lawyers said they’d received a tape recording from Sinatra’s lawyers of me supposedly misrepresenting myself as Sinatra’s authorized biographer, and this tape recording was the proof that they were going to present in court.

Now I was scared, even though I knew I hadn’t made such a telephone call. But I began to second-guess myself, wondering if maybe under the pressure I’d snapped my cap. By the time the lawyers arrived that Monday morning I was ready for handcuffs.

Three teams of lawyers sat down in my living room and put the tape in the recorder. No one said a word for the first two minutes because what we heard sounded like Porky Pig flying high on helium. In a squeaky voice, Porky said he was me and Frank Sinatra told me to call for an interview. The lawyers played that tape three times and we all listened to Porky Pig again and again before anyone said a word. Then all the lawyers laughed, clearly relieved, knowing the tape was a phony. I didn’t laugh.

“This lawsuit has gone on for almost a year and now someone is willing to lie under oath to say that I misrepresented myself to get an interview.”

“Don’t worry. We’ll send this to the tape labs at U.S.C., they’ll send the report to Sinatra’s team, and we’ll file for a dismissal. Meantime, just tape all your interviews.”

I tried to explain to the lawyers that you couldn’t always tape interviews, especially in the early 1980’s, when the technology wasn’t sophisticated. Taping in restaurants was difficult over the clinking of glasses, and taping phone interviews wasn’t legal in every state, even with two-party permission.

I finally decided that the best way to protect myself was to write a thank-you note to everyone I interviewed. That turned out to be 800 notes. They were polite and also protective. I’d thank them for the time they gave me in their home or their office or their favorite bar—wherever we’d done the interview; I’d compliment them on the polka dot bow tie they wore or the pretty pink blouse or their red tennis shoes; I’d mention the fabulous décor, or a particular piece of art, or our great salad in such-and-such a restaurant—any detail that set the time or place. Then I’d send it off and keep a copy in my files, because three or four years later when the book was finally published, they might very well have forgotten that interview or, more likely, wish they had.

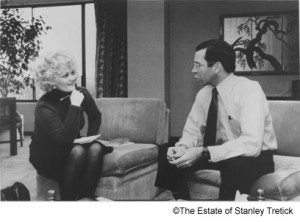

That happened with Frank Sinatra Jr. He’d agreed to be interviewed when he was performing in Washington, D.C. His representative asked if I’d be bringing a camera crew, and I said no crew, just a still photographer. Then I quickly called my friend Stanley Tretick, one of President Kennedy’s favorite photographers who had worked for UPI and then LOOK magazine.

Stanley and I arrived at the Capitol Hill Hilton in the afternoon and went to Sinatra’s suite. His publicist met us and then disappeared when Frank Jr. entered the room. Sinatra’s only son sat down and asked me to sit close to him because he didn’t want to strain his voice. He was performing that night. So, I moved over, notebook in hand. The first 30 minutes of the interview went well as Sinatra Jr. talked about accompanying his father on tour and hanging out in Vegas with his father’s friends. Then he leaned over and said, “Hon, I know what happened to Jimmy Hoffa.”

I didn’t move. Because no one knew what happened to Jimmy Hoffa. They knew he was dead, but they didn’t know how or by whom. And now the son of a mob-connected man was going to tell me.

For a split second I wondered what I should wear when I got the Pulitzer Prize.

Just as Frank Sinatra Jr. leaned over to whisper in my ear, Stanley dropped his camera bags on the floor, and said, “Well out with it, man. What the hell happened to Hoffa?”

Frank Sinatra Jr. reared back as if he’d been clubbed. He looked at me, then he bolted from his chair and ran into the bedroom, slamming the door. His publicist came running out and said we had to leave. I begged for more time, saying the interview wasn’t finished, but the publicist was physically pushing us out the door.

Up to that point, Stanley Tretick had been one of my closest friends. Now I looked at him as if he’d just been possessed by the Tasmanian devil.

“Aw, hell. He doesn’t know what happened to Jimmy Hoffa.”

“Really?” I said. “And since when are photographers clairvoyant? And what kind of a lunkhead photographer throws a hissy in the middle of a reporter’s interview? Did it ever occur to you that what the son of a mob-connected man has to say about the disappearance of Jimmy Hoffa might be of interest?”

By now I was down the steps and storming the street to hail a cab. I refused to ride in the same car with a crazy person when I was homicidal. I didn’t speak to Stanley for some time, but he became my best pal again when the Sinatra biography was published. By then Frank Sinatra had dropped his lawsuit but his son now decided to sue, denying he’d ever given me an interview. His lawyers contacted my publisher and everyone braced for another lawsuit. But Stanley produced one of the photos he’d taken during our interview that showed me sitting next to Frank Sinatra Jr. with a notebook in [my] hand and a tape recorder on the table.

That photograph certainly trumped all of my little thank-you notes. Yet I can’t tell you how many times those notes saved me. When I wrote the Nancy Reagan biography, letters rained down on Simon & Schuster from corporate tycoons and all manner of political operatives, who took offense with the words attributed to them or to their wives or secretaries or associates, and at the bottom of every letter was a “cc” to President Ronald Reagan. Each time the publisher’s lawyer would call me to go over my notes and my tapes, and then he’d send a courteous reply, saying the publisher stands by the book and its accuracy.

At first, I wanted the publisher to “cc: President Reagan” just like all the letter writers had done, but the lawyer said no reason to stir the beast. “Those are weasel letters. They’re sent simply to show the flag.” He was right, and there were no retractions and no lawsuits.

That controversial biography became the cover of Time, Newsweek, People, Entertainment Weekly, and The Columbia Journalism Review, and [was] presented on the front pages of The New York Times, The New York Post, and the New York Daily News.

On the day of publication, President and Mrs. Reagan held a press conference to denounce the book, saying that I had—quote—“clearly exceeded the bounds of decency.” And three days later, President Richard Nixon agreed. President Nixon wrote a letter to President Reagan to commiserate. President Reagan responded, saying that everyone he knew had denied talking to the author. Reagan even named the minister of his church, who’d been cited as a source, and the minister had written a denial to all his parishioners in the Bel Air Presbyterian Church bulletin.

Now, I really tried not to respond to every accusation, but this one from a man of the cloth got to me, and I wrote to remind him of the 45 minute interview he’d given in his office. I enclosed a transcript of his taped remarks and asked him to please send around another church bulletin—with a correction. Of course, he didn’t, which proves the wisdom of Winston Churchill, who said that a lie flies halfway around the world before the truth gets its pants on.

Having rankled President Reagan and President Nixon, I later rattled President George Herbert Walker Bush. I’d written to him as a matter of courtesy, when I was under contract to Doubleday to write a historical retrospective of the Bush family, and said I’d appreciate an interview sometime at his convenience.

President Bush never responded to me but he directed his aide to write my publisher, saying:

“President Bush has asked me to say that he and his family are not going to cooperate with this book because the author wrote a book about Nancy Reagan that made Mrs. Reagan unhappy.” First Lady Barbara Bush had been so incensed when she saw my books displayed in the First Ladies Exhibit at the Smithsonian that she directed the curator to remove the display, which he did the next day. In fact, I might not have known about it had I not taken my niece to the Smithsonian a few weeks before and we’d seen the display and took a picture of it.

That photograph now hangs in my guest bathroom next to autographed cartoons from Jules Feiffer and Garry Trudeau. Over the years, that loo has become crowded with cartoons from all of my various books. My sister was very impressed when she saw them. She said to my husband, “I think it’s great that Kitty has put up all the bad ones.” My husband said, “There were no good ones.”

My biography on the Bush family dynasty was published in 2004, in the midst of a contentious presidential campaign. Bush Jr. was running for a second term, and I was lambasted by his White House press secretary, the White House deputy press secretary, the White House communications director, the Republican National Committee, and the house majority leader, Tom DeLay. Mr. DeLay even wrote a colorful letter to my publisher, saying that I was—quote—“in the advanced stage of a pathological career” and the publisher was in—quote—“moral collapse for publishing such a scandalous enterprise.”

When the Bush book became number one on the New York Times bestseller list, I was dropped from the masthead of The Washingtonian Magazine, where I’d been a contributing editor for 30 years. The new owner of the magazine was a Bush presidential appointee. The editor told me, “Your book was too personal. Too revealing.”

“But that’s what a biography is,” I said. “It’s an intimate examination of a person in his times, and in this case a powerful person in the public arena. The President of the United States influences our society, with actions that affect our lives.”

I quoted the actor Melvyn Douglas from the movie Hud. He talked about the mesmerizing power of a public image: “Little by little the look of the country changes because of the men we admire.” And Colum McCann, in his novel Let the Great World Spin, wrote: “Repeated lies become history, but they don’t necessarily become the truth.”

This is why biography is so vital to a healthy society. Whether authorized or unauthorized, biography presents a life story—sometimes it’s an x-ray of a manufactured image, sometimes it’s a gauzy bandage. The best biographers try to penetrate dross and drill for gold. As President Kennedy said, “The great enemy of the truth is very often not the lie—deliberate, contrived and dishonest—but the myth, persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic.”

I do not relish living in a world where information is authorized, sanitized, and homogenized. I read banned books. I applaud whistleblowers and I reject any suppression by church or state. To me, the unauthorized biography, which requires a combination of scholarly research and investigative reporting, is best directed at those figures still alive and able to defend themselves, who exercise power over our lives. . . . I firmly believe that unauthorized biography can be a public service and a boon to history.

The most solid support I’ve received over the years has come from writers—journalists and historians and biographers—who believe in the First Amendment. Who champion the public’s right to know.

These are principles that feed my soul and fill my heart, which is why I’m so grateful to be honored by you today with this award.

Thank you.

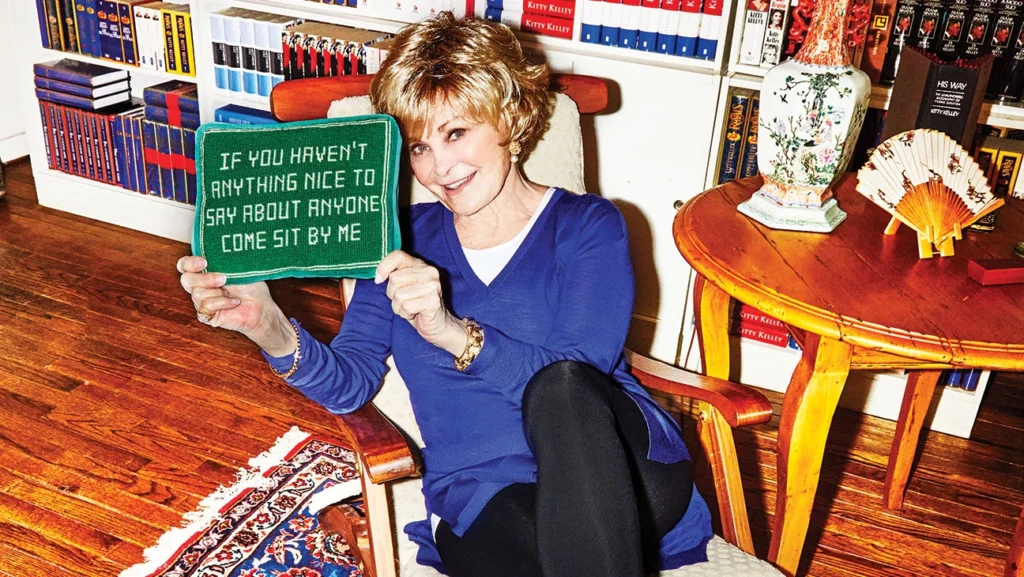

Queen of the Unauthorized Biography Spills Her Own Secrets

By Seth Abramovitch

There was, not that long ago, a name whose mere invocation could strike terror in the hearts of the most powerful figures in politics and entertainment.

That name was Kitty Kelley.

If it’s unfamiliar to you, ask your mother, who likely is in possession of one or more of Kelley’s best-selling biographies — exhaustive tomes that peer unflinchingly (and, many have claimed, nonfactually) into the personal lives of the most famous people on the planet.

“I’m afraid I’ve earned it,” sighs Kelley, 79, of her reputation as the undisputed Queen of the Unauthorized Biography. “And I wave the banner. I do. ‘Unauthorized’ does not mean untrue. It just means I went ahead without your permission.”

That she did. Jackie Onassis, Frank Sinatra, Nancy Reagan — the more sacred the cow, the more eager Kelley was to lead them to slaughter. In doing so, she amassed a list of enemies that would make a despot blush. As Milton Berle once cracked at a Friars Club roast, “Kitty Kelley wanted to be here tonight, but an hour ago she tried to start her car.”

Only a handful of contemporary authors have achieved the kind of brand recognition that Kelley has. At the height of her powers in the early 1990s, mentions of the ruthless journo with the cutesy name would pop up everywhere from late night monologues to the funny pages. (Fully capable of laughing at herself, her bathroom walls are covered in framed cartoons drawn at her expense.)

Kelley is hard to miss around Washington, D.C. She drives a fire-engine red Mercedes with vanity plates that read “MEOW.” The car was a gift from former Simon & Schuster chief Dick Snyder, who was determined to land Kelley’s Nancy Reagan biography.

“Simon & Schuster said, ‘Kitty, Dick really wants the book. What will it take to prove that?’ ” she recalls. “I said,  ‘A 560 SL Mercedes, bright red, Palomino interior.’ ‘We’ll be back to you.’ ” She insists she was only kidding. But a few days later, Kelley answered the phone and was directed to walk to the nearest corner: “Your bright red 560 SL is sitting there waiting for you.” Sure enough, there it was. The “MEOW” plates were a surprise gift from the boyfriend who would become her second husband, Dr. John Zucker.

‘A 560 SL Mercedes, bright red, Palomino interior.’ ‘We’ll be back to you.’ ” She insists she was only kidding. But a few days later, Kelley answered the phone and was directed to walk to the nearest corner: “Your bright red 560 SL is sitting there waiting for you.” Sure enough, there it was. The “MEOW” plates were a surprise gift from the boyfriend who would become her second husband, Dr. John Zucker.

Ask Kelley how many books she has sold, and she claims not to know the exact number. It is many, many millions. Her biggest sellers — 1986’s His Way, about Frank Sinatra, and 1991’s Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography, began with printings of a million each, which promptly sold out. “But they’ve gone to 12th printings, 14th printings,” she says. “I really couldn’t tell you how many I’ve sold in total.” She does recall first breaking into The New York Times‘ best-seller charts, with 1978’s Jackie Oh! “I remember the thrill of it. I remember how happy I was. It’s like being prom queen,” she says. “Which I actually was about 100 years ago.”

Regardless of one’s opinions about Kelley, or her methodology, there can be no denying that her brand of take-no-prisoners celebrity journalism — the kind that in 2022 bubbles up constantly in social media feeds in the form of TMZ headlines and gossipy tweets — was very much ahead of its time.

In fact, a detail from Kelley’s 1991 Nancy Reagan biography trended in December when Abby Shapiro, sister of conservative commentator Ben Shapiro, tweeted side-by-side photos of Madonna and the former first lady. “This is Madonna at 63. This is Nancy Reagan at 64. Trashy living vs. Classic living. Which version of yourself do you want to be?” read the caption. Someone replied with an excerpt from Kelley’s biography that described Reagan as being “renowned in Hollywood for performing oral sex” and “very popular on the MGM lot.” The excerpt went viral and launched a wave of memes. “It doesn’t fit with the public image. Does it? It just doesn’t. And the source on that was Peter Lawford,” says Kelley, clearly tickled that the detail had resurfaced.

While amplifying those kinds of rumors might not suggest it, in many eyes, Kelley is something of a glass-ceiling shatterer. “Back when she started in the 1970s, it was a largely male profession,” says Diane Kiesel, a friend of Kelley’s who is a judge on the New York Supreme Court. “She was a trailblazer. There weren’t women writing the kind of hard-hitting books she was writing. I’m sure most of her sources were men.”

But what of her methodology? Kelley insists she never sets out to write unauthorized biographies. Since Jackie Oh!, she has always begun her research by asking her subjects to participate, often multiple times. She is invariably turned down, then continues about the task anyway. She’s also known to lean toward blind sourcing and rely on notes, plus tapes and photographs, to back up the hundreds of interviews that go into every book.

“Recorders are so small today, but back then it was very hard to carry a clunky tape recorder around and slap it on the table in a restaurant and not have all of that ambient noise,” she says. To prove the conversations happened, Kelley devised a system in which she would type up a thank-you note containing the key details of their meeting — location, date and time — and mail it to every subject, keeping a copy for herself. If a subject ever denied having met with her, she would produce the notes from their conversation and her copy of the thank-you note.

So far, the system has worked. While many have tried to take her down, the ever-grinning Kelley has never been successfully sued by a source or subject.

Now 79, she lives in the same Georgetown townhouse she purchased with her $1.5 million advance (that’s $4 million adjusted for inflation) for His Way, which the crooner unsuccessfully sued to prevent from even being written.

Among the skeletons dug up by Kelley in that 600-page opus: that Ol’ Blue Eyes’ mother was known around  Hoboken, New Jersey, as “Hatpin Dolly” for a profitable side hustle performing illegal abortions. Sinatra’s daughter Nancy Sinatra said the family “strangled on our pain and anger” over the book’s release, while her sister, Tina, said it caused her father so much stress, it forced him to undergo a seven-and-a-half-hour surgical procedure on his colon.

Hoboken, New Jersey, as “Hatpin Dolly” for a profitable side hustle performing illegal abortions. Sinatra’s daughter Nancy Sinatra said the family “strangled on our pain and anger” over the book’s release, while her sister, Tina, said it caused her father so much stress, it forced him to undergo a seven-and-a-half-hour surgical procedure on his colon.

Giggly, vivacious and 5-foot-3, Kelley presents more like a kindly neighbor bearing blueberry muffins than the most infamous poison-pen author of the 20th century. “I seem to be doing more book reviewing than book writing these days,” she says in one of our first correspondences and points me to a review of a John Lewis biography published in the Washington Independent Review of Books.

She has not tackled a major work since 2010’s Oprah — a biography of Oprah Winfrey touted ahead of its release by The New Yorker as “one of those King Kong vs. Godzilla events in celebrity culture” but which fizzled in the marketplace, barely moving 300,000 copies. Among its allegations: that Winfrey had an affair early in her career with John Tesh — of Entertainment Tonight fame — and that, according to a cousin, the talk show host exaggerated tales of childhood poverty because “the truth is boring.”

“We had a falling out because I didn’t want to publish the Oprah book,” says Stephen Rubin, a consulting publisher at Simon & Schuster who grew close to Kelley while working with her at Doubleday on 2004’s The Family: The Real Story of the Bush Dynasty.

“I told her that audience doesn’t want to read a negative book about Saint Oprah. I don’t think it’s something she should have even undertaken. We have chosen to disagree about that.”

The book ended up at Crown. It would be nine months before Kelley would speak to Rubin again. They’ve since reconciled. “She’s no fun when she’s pissed,” Rubin notes.

Adds Kelley of Winfrey’s reaction to the book: “She wasn’t happy with it. Nobody’s happy with [an unauthorized] biography. She was especially outraged about her father’s interview.” She is referencing a conversation she had, on the record, with Winfrey’s father, Vernon Winfrey, in which he confirmed the birth of her son, who arrived prematurely and died shortly after birth.

But Kelley says the backlash to Oprah: A Biography and the book’s underwhelming sales had nothing to do with why she hasn’t undertaken a biography since. Rather, her husband, a famed allergist in the D.C. area who’d give a daily pollen report on television and radio, died suddenly in 2011 of a heart attack. “John was the great love of her life,” says Rubin. “He was an irresistible guy — smart, good-looking, funny and mad for Kitty.”

“Boy, I was knocked on my heels,” she says of Zucker’s death. “He hated the cold weather. He insisted we go out to the California desert. We were in the desert, and he died at the pool suddenly. I can’t account for a couple of years after that. It was a body blow. I just haven’t tackled another biography since.”

A decade having passed, Kelley does not rule out writing another one — she just hasn’t yet found a subject worthy of her time. “I can’t think of anyone right now who I would give three or four years of my life to,” Kelley says. “It’s like a college education.”

For fun, I throw out a name: Donald Trump. Kelley shakes her head vigorously. “I started each book with real respect for each of my subjects,” she says. “And not just for who they were but for what they had accomplished and the imprint that they had left on society. I can’t say the same thing about Donald Trump. I would not want to wrap myself in a negative project for four years.”

“You know,” I interrupt, “I’m imagining people reading that quote and saying, ‘Well, you took ostensibly positive topics and turned them into negative topics.’ How would you respond to that?”

“I would say you’re wrong,” Kelley replies. “That’s what I would say. I think if you pick up, I don’t know — the Frank Sinatra book, Jackie Oh!, the Bush book — yes, you’re going to see the negatives and the positives, which we all have. But I think you’ll come out liking them. I mean, we don’t expect perfection in the people around us, but we seem to demand it in our stars. And yet, they’re hardly paragons. Each book that I’ve written was a challenge. But I would think that if you read the book, you’re going to come out — no matter what they say about the author — you’re going to come out liking the subject.”

***

Kelley arrived in the nation’s capital in 1964. She was 22 and, through the connections of her dad, a powerful attorney from Spokane, Washington, she landed an assistant job in Democratic Sen. Eugene McCarthy’s office. She worked there for four years, culminating in McCarthy’s 1968 presidential bid. It was a tumultuous time. McCarthy’s Democratic rival, Robert F. Kennedy, was gunned down in Los Angeles at a California primary victory party on June 5. When Hubert Humphrey clinched the nomination that August amid the DNC riots in Chicago, Kelley’s dreams of a future in a McCarthy White House were dashed, and she decided a life in politics was not for her.

“But I remain political,” Kelley clarifies. “I am committed to politics and have been ever since I worked for Gene McCarthy. I was against the war in Vietnam. I don’t come from that world. I come from a rich, right-wing Republican family. My siblings avoid talking politics with me.”

In 1970, she applied for a researcher opening in the op-ed section at The Washington Post. “It was a wonderful job,” she recalls. “I’d go into editorial page conferences. And whatever the writers would be writing, I would try and get research for them. Ben Bradlee’s office was right next to the editorial page offices. And if he had both doors open, I would walk across his office. He was always yelling at me for doing it.”

According to her own unauthorized biography — 1991’s Poison Pen, by George Carpozi Jr. — Kelley was fired for taking too many notes in those meetings, raising red flags for Bradlee, who suspected she might be researching a book about the paper’s publisher, Katharine Graham. Kelley says the story is not true.

“I have not heard that theory, but I will tell you I loved Katharine Graham, and when I left the Post, she gave me a gift. She dressed beautifully, and when the style went from mini to maxi skirts —because she was tall and I am not, I remember saying, ‘Mrs. Graham, you’re going to have to go to maxis now. And who’s going to get your minis?’ She laughed. It was very impudent. But then I was handed a great big box with four fabulous outfits in them — her miniskirts.”

Kelley says she left the Post after two years to pursue writing books and freelancing. She scored one of the bigger scoops of 1974 when the youngest member of the upper house — newly elected Democratic Sen. Joe Biden of Delaware, then 31 — agreed to be profiled for Washingtonian, a new Beltway magazine.

Biden was still very much in mourning for his wife and young daughter, killed by a hay truck while on their way to buy a Christmas tree in Delaware on Dec. 18, 1972. The future president’s two young sons, Beau and Hunter, survived the wreck; Biden was sworn into the Senate at their hospital bedsides.

After the accident, Biden developed an almost antagonistic relationship to the press. But his team eventually softened him to the idea of speaking to the media. That was precisely when Kelley made her ask.

Biden would come to deeply regret the decision. The piece, “Death and the All-American Boy,” published on June 1, 1974, was a mix of flattery (Kelley writes that Biden “reeks of decency” and “looks like Robert Redford’s Great Gatsby”), controversy (she references a joke told by Biden with “an antisemitic punchline”) and, at least in Biden’s eyes, more than a little bad taste.

The piece opens: “Joseph Robinette Biden, the 31-year-old Democrat from Delaware, is the youngest man in the Senate, which makes him a celebrity of sorts. But there’s something else that makes him good copy: Shortly after his election in November 1972 his wife Neilia and infant daughter were killed in a car accident.”

Later, Kelley writes, “His Senate suite looks like a shrine. A large photograph of Neilia’s tombstone hangs in the inner office; her pictures cover every wall. A framed copy of Milton’s sonnet ‘On His Deceased Wife’ stands next to a print of Byron’s ‘She Walks in Beauty.’ “

But it was one of Biden’s own quotes that most incensed the future president.

She writes: ” ‘Let me show you my favorite picture of her,’ he says, holding up a snapshot of Neilia in a bikini. ‘She had the best body of any woman I ever saw. She looks better than a Playboy bunny, doesn’t she?’ “

“I stand by everything in the piece,” says Kelley. “I’m sorry he was so upset. And it’s ironic, too, because I’m one of his biggest supporters. It was 48 years ago. I would hope we’ve both grown. Maybe he expected me to edit out [the line about the bikini], but it was not off the record.” Still, she admits her editor, Jack Limpert, went too far with the headline: “I had nothing to do with that. I was stunned by the headline. ‘Death and the All-American Boy.’ Seriously?”

It would be 15 years before Biden gave another interview, this time to the Washington Post‘s Lois Romano during his first presidential bid, in 1987. Biden, by then remarried to Jill Biden, recalled to Romano, “[Kelley] sat there and cried at my desk. I found myself consoling her, saying, ‘Don’t worry. It’s OK. I’m doing fine.’ I was such a sucker.”

Kelley’s first book wasn’t a biography at all. “It was a book on fat farms,” she says, which was based on a popular article she’d written for Washington Star News on San Diego’s Golden Door — one of the country’s first luxury spas catering to celebrity clientele like Natalie Wood, Elizabeth Taylor and Zsa Zsa Gabor.

“On about the third day, the chef came out, and he said, ‘Would you like a little something?’ ” says Kelley. “He was Italian. I said, ‘Yes, I’m so hungry.’ And he kind of laughed. Turns out he wasn’t talking about tuna fish. I said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me.’ He said, ‘I have sex all the time with the people here.’ I said, ‘I should tell you, I’m here writing a book.’ He said, ‘I’ll tell you everything!’ I warned him, ‘OK — but I’m going to use names.’ And I did.”

The book, a 1975 paperback called The Glamour Spas, sold “14 copies, all of them bought by my mother,” she says. But the publisher, Lyle Stuart, dubbed in a 1969 New York Times profile as the “bad boy of publishing,” was impressed enough with Kelley’s writing that he hired her in 1976 to write a biography of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

The crown jewel of the book that would become Jackie Oh! was Kelley’s interview with Sen. George Smathers, a Florida Democrat and John F. Kennedy’s confidant. (After they entered Congress the same year and quickly became close friends, Kennedy asked Smathers to deliver two significant speeches: at his 1953 wedding and his 1960 DNC nomination.)

“It was quite explosive,” Kelley recalls of her three-hour dinner with Smathers. “He was very charming, very Southern and funny. And he said, ‘Oh, Jack, he just loved women.’ And he went on talking, and he said, ‘He’d get on top of them, just like a rooster with a hen.’ I said, ‘Senator, I’m sorry, but how would you know that unless you were in the room?’ He said, ‘Well, of course I was in the room. Jack loved doing it in front of people.’

“The senator, to his everlasting credit, did not deny it,” Kelley continues. “A reporter asked him, ‘Did you really say those things?’ And the senator replied, ‘Yeah, I did. I think I was just run over by a dumb-looking blonde.’ “

She followed that one, which landed on the New York Times best-seller list, with 1981’s Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star, which underwhelmed. Her next two, however — His Way and Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography (for which she earned a $3.5 million advance, $9 million in 2022 adjusted for inflation) — were best-sellers, moving more than 1 million copies each in hardcover.

She followed that one, which landed on the New York Times best-seller list, with 1981’s Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star, which underwhelmed. Her next two, however — His Way and Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography (for which she earned a $3.5 million advance, $9 million in 2022 adjusted for inflation) — were best-sellers, moving more than 1 million copies each in hardcover.

Her 1997 royal family exposé, The Royals — which presaged The Crown, the Lady Di renaissance and Megxit mania by several decades — contained allegations that the British royal family had obfuscated their German ancestry.

“Sinatra was huge and Nancy was huge, but The Royals gave me more foreign sales than I’ve ever had on any book,” Kelley beams, adding that the recent headlines about Prince Andrew settling with a woman who accused him of raping her as a teenager at Jeffrey Epstein’s compound “really shows the rotten underbelly of the monarchy, in that someone would be so indulged, really ruined as a person, without much purpose in life.”

“Looking around,” I ask Kelley, “is society in decline?”

“What a question,” she replies. “Let’s say it’s being stressed on all sides. I think it’s become hard to find people that we can look up to — those you can turn to to find your better self. We used to do that with movie stars. People do it with monarchy. Unfortunately, there are people like Kitty Kelley around who will take us behind the curtain.”

Contrary to her public persona, Kelley is known in D.C. social circles for her gentility. Judge Kiesel, a part-time author, first met her eight years ago when Kelley hosted a reception for members of the Biographers International Organization at her home.

“What amazed me was she was such the epitome of Southern hospitality, even though she isn’t from the South,” says Kiesel. “I remember her standing on the front porch of her beautiful home in Georgetown and personally greeting every member of this group who had showed up. There had to be close to 200 of us.”

Kelley hosts regular dinner parties of six to 10 people. “She likes to mix people from publishing, politics and the law,” says Kiesel. When Kiesel, who lives in New York City, needed to spend more time in D.C. caring for a sister diagnosed with cancer, Kelley insisted she stay at her home. “She threw a little dinner party in my honor,” Kiesel recalls. “I said, ‘Kitty — why are you doing this?’ She said, ‘You’re going to have a really rough couple of months and I wanted to show you that I’m going to be there for you.’ People look at her as this tough-as-nails, no-holds-barred writer — but she’s a very kind, sweet, generous woman.”

For Kelley, life has grown pretty quiet the past few years: “It’s such a solitary life as a writer. The pandemic has turned life into a monastery.” Asked whether she dates, she lets out a high-pitched chortle. “Yes,” she says. “When asked. No one serious right now. Hope springs eternal!”

I ask her if there is anything she’s written she wishes she could take back. “Do I stand by everything I wrote? Yes. I do. Because I’ve been lawyered to the gills. I’ve had to produce tapes, letters, photographs,” she says, then adds, “But I do regret it if it really brought pain.”

Says Rubin: “People think she’s a bottom-feeder kind of writer, and that’s totally wrong. She’s a scrupulous journalist who writes no-holds-barred books. They’re brilliantly reported.”

Before I bid her adieu, I can’t resist throwing out one more potential subject for a future Kelley page-turner.

“What about Jeff Bezos?” I say.

She pauses to consider, and you can practically hear the gears revving up again.

“I think he’s quite admirable,” she says. “First of all, he saved The Washington Post. God love him for that. And he took on someone who threatened to blackmail him. He stood up to it. I think there’s much to admire and respect in Jeff Bezos. He sounds like he comes from the most supportive parents in the world. You don’t always find that with people who are so successful.”

“So,” I say. “You think you have another one in you?”

“I hope so,” Kelley says. “I know you’re going to end this article by saying … ‘Look out!’ “

This story first appeared in the March 2 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine.

https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/lifestyle/arts/kitty-kelley-interview-unauthorized-biographies-1235101933/

Photo credits: top of page, Amy Lombard; Kitty Kelley in Merc, Amy Lombard; Kitty Kelly with His Way, Bettmann/Getty Images; Kitty Kelley with Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star, Harry Hamburg/NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images

BIO Podcast

Kitty Kelley spoke with BIO member John A. Farrell in February 2020 in Washington, D.C.

Kitty Kelley spoke with BIO member John A. Farrell in February 2020 in Washington, D.C.

Part I (26:53):

Part II (26:26):

John A. Farrell’s website: http://www.jafarrell.com/

Biographers International Organization: https://biographersinternational.org/

BIO Podcasts: https://biographersinternational.org/podcasts/

Part I URL:

https://biographersinternational.org/news/podcast/podcast-episode-45-kitty-kelley-part-i/?fbclid=IwAR0N2CMGj5Fzg5bY4Rx1VsXkGCd2HHri1K0jOKHbgf8x4uJlIwGliZWGlFI

Part II URL:

https://biographersinternational.org/news/podcast/podcast-episode-46-kitty-kelley-part-ii/?fbclid=IwAR1xJI97oOu5YbQSP2_4M6dl1DABV7g12Wnzcjp2MpdbU4fr5tHY3683kOg

BIO Board of Directors

- Linda Leavell, President (2019-2021)

- Sarah S. Kilborne, Vice President (2020-2022)

- Marc Leepson, Treasurer (2019-2021)

- Billy Tooma, Secretary (2020-2022)

- Kai Bird (2019-2021)

- Deirdre David (2019-2021)

- Natalie Dykstra (2020-2022)

- Carla Kaplan (2020-2022)

- Kitty Kelley (2019-2021)

- Heath Lee (2019-2021)

- Steve Paul (2020-2022)

- Anne Boyd Rioux (2019-2021)

- Marlene Trestman (2019-2021)

- Eric K. Washington (2020-2022)

- Sonja Williams (2019-2021)

Kitty Kelley on Frank Sinatra

Who would’ve thought that we’d be here tonight celebrating the 100th birthday of Frank Sinatra???

Some of you were with me thirty years ago when I was researching his life story and Sinatra sued to stop me. He said then that only he alone or someone he authorized had the right to write about his life. The day he hit me with his $2 million lawsuit was the day I fully understood what the First Amendment was all about.

it hadn’t been for the support I received from writers groups around the country like the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, Sigma Delta Chi, the Newspaper Guild, PEN, the American Society of Journalists and Authors, the National Writers Union, the Council of Writers Organizations and Washington Independent Writers, I could not have written this book. So I remain profoundly grateful to those writers who understood how a powerful man with money and influence could try to exercise prior restraint and bury a writer before she had written a word.

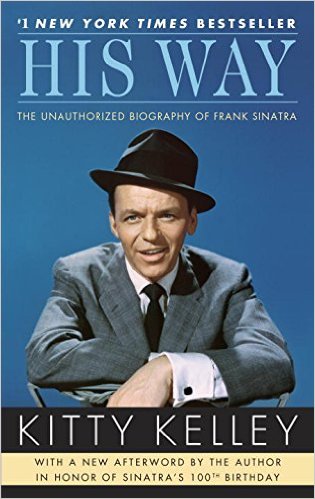

After a year-long battle Frank Sinatra finally dropped his lawsuit and His Way: the Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra was published. Now it’s been updated and re-released to coincide with his centennial.

For me the best part of tonight is that the life story of a man with only 47 days of education before he dropped out of high school in Hoboken, New Jersey will benefit Reading is Fundamental. This organization is the largest non-profit for children’s literacy in the United States. So the more books you buy tonight, the more books Reading is Fundamental can put in the hands of poor children who’ve never owned a book. Possessing their own books will help them learn to read and to become literate, and their literacy will benefit all of us. Now even Frank Sinatra could not object to that.

So let’s hoist a glass to Ole Blue Eyes and to the First Amendment and to all those who made this evening possible.

Kitty Kelley made these remarks at a party and book signing celebrating the release of the Frank Sinatra centennial edition of His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra. The event took place on December 9, 2015 at i Ricchi restaurant in Washington DC.

Frank Sinatra Centennial "His Way"

A new edition of Kitty Kelley’s His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra has been released for Frank Sinatra’s 100th birthday, December 12, 2015. This edition has a new Afterword. The re-release was celebrated with a book signing at i Ricchi in Georgetown in D.C. for the benefit of Reading Is Fundamental.

Reissued in honor of Frank Sinatra’s 100th birthday, HIS WAY: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra (A Bantam Trade Paperback Reissue) is #1 New York Times bestselling author Kitty Kelley’s backstage pass into the life of one of the most extraordinary and complicated men to fill the public consciousness. Featuring a new afterword, this reissue shares Kelley’s insider take on developments in the Sinatra estate since the book’s original release: the commercialization of the Sinatra brand by his children after his death; the feud between Frank’s children and his fourth and final wife, Barbara Sinatra; the ongoing spectacle of alleged paternity questions; and even the impact of the book itself on Frank’s life and career.

Statement, ASJA Awards Presentation, April 24, 2014

On April 24, 2014, Kitty Kelley was presented with the Founders’ Award for Career Achievement by the American Society of Journalists and Authors (ASJA) during a ceremony at the group’s 43rd annual writers’ conference in New York. The following are her remarks at the Awards Presentation.

My love affair with the American Society of Journalists and Authors began on September 21, 1983 when we were introduced by Frank Sinatra. That was the day he sued me for $2 million to keep me from writing his (decidedly unauthorized) biography. In court papers, he declared that he and he alone or someone that he authorized could write his life story. No one else was entitled to what he called his “right of publicity.”

ASJA immediately stepped forward and joined with other writers’ groups to protest Sinatra’s assault on the First Amendment. In a press conference, they said: “The apparent goal behind Sinatra’s filing of this suit is to scare Ms. Kelley away from her investigation and ultimately to force her to scrap the book.” They asserted that “the unauthorized or unblessed biography” is the essence of free speech and open commentary and declared that Sinatra’s lawsuit was an assault on all writers’ constitutionally protected freedom of expression and should be dismissed on its face.

This public stance stirred a great deal of publicity from outraged journalists, who wrote columns, editorials, and even a few cartoons. One of the funniest was drawn by Jules Feiffer, who showed a mug’s face under a snap-brim hat, swaying on skinny legs and snapping his fingers:

showed a mug’s face under a snap-brim hat, swaying on skinny legs and snapping his fingers:

“I’m chairman of the Board. If some broad wantsa write a book about me… She gotta talk t’one of my boys who talks t’one of my other boys… who talks t’me. And MAYBE if the broad looks OK, I say, ‘Go Baby.’ Or Maybe I say ‘Shove it, Bimbo.’ And before she can write word one I sue her.

“So don’t give me any First Amendment crapola, I got the Frank Amendment and mine is bigger than hers. Ring a ding ding.”

After a year of litigation that cost me over $100,000 in legal fees, Sinatra finally dropped his lawsuit, but by then he had sent his message to my publisher and the rest of the world that he did not want the book written. Many people were too frightened to speak on the record, and some actually feared for their lives, but over the course of three years I managed to interview 800 people, including members of Sinatra’s family, his mistresses, co-stars, friends, neighbors, employees, FBI agents, a few antagonists, and a couple of mobsters.

In 1986 His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra was published, and– despite his threats– I lived to see the book become number one on the New York Times best seller list and sell more than 1 million copies in hardback. All very gratifying, but best of all was receiving ASJA’s Outstanding Author Award that year for “courageous writing on popular culture.”

Publication of the Frank Sinatra biography was a triumph for all non-fiction writers who struggle against immense pressure to find their way to examine the public figures who influence our society.

Thirty years ago ASJA made it possible for me to find my way– and for that I am profoundly grateful. I accept your award for Career Achievement because YOU made my career all it has been– and I thank you from the bottom of my heart.

by Kitty Kelley

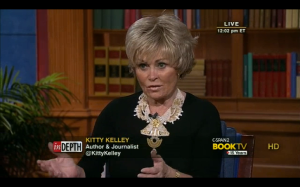

Kitty Kelley on Book-TV

Kitty Kelley appeared on C-Span2’s Book-TV “In Depth” program on Sunday, Nov. 3, 2013, answering questions from host Peter Slen and from viewers for three hours. The show may be viewed online here.

Ebooks Note

All seven bestselling biographies by Kitty Kelley are now available as ebooks.

Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star

His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra

Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography

Before Barbara Sinatra

by Kitty Kelley

It was only natural that I read Barbara Sinatra’s memoir, Lady Blue Eyes, published recently. How could I not? After all, I had spent four years researching and writing a biography of her husband in 1986: His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra.

It was only natural that I read Barbara Sinatra’s memoir, Lady Blue Eyes, published recently. How could I not? After all, I had spent four years researching and writing a biography of her husband in 1986: His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra.

The book became number one on the New York Times best seller list and sold over 1 million copies in hardback, but the subject sued me before I ever wrote a word, saying that he and he alone or someone that he authorized was entitled to write his life story. He dropped his lawsuit after a year, but by then he had effectively put the world on notice that he did not want the book written by someone who was not in his control.

Mrs. Sinatra writes in her memoir that Frank despised the press with the sole exception of former TV host Larry King, novelist Pete Hamill, and the late James Bacon, who wrote a Hollywood column for the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner. No surprise there as each man genuflected to “Ole Blue Eyes.” And there was much to admire in the man—his monumental talent, great showmanship and unparalleled philanthropy. But there was also a dark side, violent and frightening.

Mrs. Sinatra writes in her memoir that Frank despised the press with the sole exception of former TV host Larry King, novelist Pete Hamill, and the late James Bacon, who wrote a Hollywood column for the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner. No surprise there as each man genuflected to “Ole Blue Eyes.” And there was much to admire in the man—his monumental talent, great showmanship and unparalleled philanthropy. But there was also a dark side, violent and frightening.

In researching His Way, I traveled to Hoboken, Manhattan, Hollywood, Las Vegas and Palm Springs to interview Sinatra’s relatives, friends, employees, co-stars, musicians, business associates, directors, producers, and former lovers, most of whom spoke on the record. Yes, there was a long line of women—show girls, call girls, movie stars, manicurists, even the wives of some of his best friends. But aside from his own wives, most of Sinatra’s women were simply there to help him make it through the night.

An exception was Nancy Gundersen, who I knew had played an important part in his life for several years before she became the wife of New York ob-gyn Martin L. Stone, M.D. Ms. Gundersen declined to be interviewed when I called her years ago. So I was surprised a few months ago when she approached me after a speech I had given for the College of the Desert in Rancho Mirage. “It’s been almost 25 years since you called,” she said, “but you can have that interview now, if you’d like.”

We both laughed, made a date for lunch the following week and spent hours comparing notes on the Frank she knew and the Frank I wrote about. Elegant, pretty, and whip smart, she was delightful, and I saw immediately why Sinatra had been so charmed.

“Frank and I met on a blind date in New York in 1970 when I was the house model for Anne Klein,” she said. “I had had been working on an M.A. in International Relations at the New School before that. He was 23 years older than me but we clicked immediately…. On our first date He gave me his antique Dunhill lighter. Anne wanted me to look great every time I went out with Frank so once she loaned me a gorgeous mink coat. Frank loved the coat and complimented me on it but I told him the truth–that it wasn’t mine, that I had borrowed it for the evening. The next day I found an envelope filled with $100 bills and a note that said: ‘Buy your own mink coat.’ So I did.

“Anne Klein loved our affair and always dressed me when Frank and I went out. One night Frank asked me to go to the theater with Loel and Gloria Guinness. I was too young to know that Gloria Guinness was a renowned beauty and supposedly the most elegant woman in the world but Anne knew what I was up against so she dressed me in a gorgeous white silk dress, cut on the bias, topped by a spectacular orange silk patch work coat that Frank just loved because, as you know, orange was his favorite color.”

Nancy Gundersen Stone recollected sweet times with Sinatra. “We had a wonderful affair for two years that melted into a deep friendship for another two years… I loved Frank, but was never in love with him… I spent many, many week-ends at his house in Palm Springs and I have to laugh as I remember the deep freeze I’d always get from Dinah Shore and the girls who were pushing him to marry Barbara Marx…. He told me Ava had been the great love of his life and that that love almost ruined him. He never got over her—ever.”

Blessed by good looks, a good education and Anne Klein, Nancy had the cachet (or “class” as Frank Sinatra said) to travel easily in all of his worlds. He flew her to Las Vegas for his shows and to weekend with him at publisher Bennett Cerf’s house in Westchester County. “I was not a show girl,” she said, “so he felt he could introduce me to all sorts of people.”

She also accompanied him to his mother’s house in New Jersey when he signed his record contract. She remembered Dolly Sinatra as “rawhide tough,” but adored by her son. “That night Frank wrote a check for her for $1 million.”

Barbara Sinatra writes in her memoir that Frank never discussed his finances with her. Yet he seems to have shared many such details with Nancy Gundersen. “When he drew up the trust funds for his kids he made sure that Frank, Jr. got his payout at the age of 21 but the girls, Nancy and Tina, could not get their money until they were 35. ‘Otherwise, they’ll marry bums,’ Frank said.”

Nancy Gundersen came to know Frank’s daughters very well, having spent so much time with them at his house in Palm Springs. “One night Frank was receiving an award at Chandler Center and he escorted Nancy Sr. and his daughters. I was driven to the ceremony by Sarge Weiss. It was a bit uncomfortable, especially when Nancy, Jr. pretended not to know me in front of her mother, but Tina, who is like her father, ran over to give me a big hug. Frank and I left right after for Palm Springs.”

Interesting to note that after 22 years of marriage to their father, Barbara Sinatra does not mention either of his daughters in her memoir. Since Frank Sinatra died in 1998, the three women have not spoken, except through lawyers. Their fights are primarily over money, although each was magnificently taken care of in Sinatra’s will. The two daughters have written books suggesting that the blond Las Vegas show girl who became their step-mother was not worthy of their father’s iconic name.

Nancy and Tina Sinatra, both of whom have been married and divorced never took their husbands’ names, preferring instead to go through life as Frank Sinatra’s daughters. And who could fault them? In its day, the Sinatra name could open any door. As Barbara Sinatra writes, she met presidents, prime ministers and potentates. She details the delights of being Lady Blue Eyes (the mansions, the mammoth jewels, the private planes, the famous friends) and the dangers (the violent fights, the black moods, the uncontrollable temper). She also dishes.

She dismisses former First Lady Nancy Reagan as a user. “[She] was never a close friend, and it had nothing to do with the fact that she seemed to have a crush on my husband…. I felt she took advantage of Frank’s huge heart…. During long distance telephone calls and their lunches together whenever they were in the same town, I think Frank became Nancy’s therapist more than her friend.”

She dismisses former First Lady Nancy Reagan as a user. “[She] was never a close friend, and it had nothing to do with the fact that she seemed to have a crush on my husband…. I felt she took advantage of Frank’s huge heart…. During long distance telephone calls and their lunches together whenever they were in the same town, I think Frank became Nancy’s therapist more than her friend.”

After telling readers that her husband, “Charlie Neat,” was obsessively clean, took three showers a day and allotted $1 million a year to himself to lose at gambling, Barbara Sinatra writes that as his wife it was her job to vet the guest list of every party to which they were invited. If there was a guest that Frank did not like, Frank did not attend. When Henry Kissinger planned a dinner in Frank’s honor, he had to submit the guest list to Barbara. Unfortunately, for Kissinger, he had invited Barbara Walters, whom Sinatra detested, so Sinatra refused to go to the party. Stunned, Kissinger called Barbara Sinatra three times, begging her to get her husband to reconsider, but Sinatra was adamant. Mrs. Sinatra told the former Secretary of State that her husband would not go anywhere Barbara Walters was present. Finally, Kissinger had no choice but to disinvite Walters. Only then would Frank Sinatra agree to attend the party in his honor.

Right, wrong or rude, the man certainly did it His Way.

Photo credits: Nancy Gundersen with Frank Sinatra, courtesy of Nancy Gundersen Stone; Frank Sinatra 1986, Frank Sinatra with the Reagans in 1985, and the author in 1986 used with permission of the Estate of Stanley Tretick.

Cross-posted from Huffington Post

Frank Sinatra and Me

by Kitty Kelley

I can’t say I wasn’t warned. Alarms started clanging the day I signed to write His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra (Bantam Books, 1986).

Some friends urged me to buy life insurance and make them the beneficiaries; others recommended bodyguards and a bullet-proof vest. The rumors of Frank Sinatra’s violence and his ties to organized crime were such that journalists joked in print about me ending up in concrete boots and sleeping with the fishes, if I proceeded to write his biography. Milton Berle joshed at the Friars Club, “Kitty Kelley wanted to be here tonight but an hour ago she tried to start her car.”

The laughs stopped when I received a message on my answering machine: “Soy-ving by Oy-ving here. Call ASAP ‘cuz we gotta soyve ya.”

I figured it was a New Jersey caterer who had the wrong number. Turns out it was a process server named Irving in the subpoena business of serving.

“Serving by Irving” was no joke. Frank Sinatra was suing me before I had written a word. In fact, the book was five years away from publication, but Sinatra wanted to make sure it would never be published. So he sued me (not my publisher) in Santa Monica, California, seeking $2 million in punitive damages, saying that he and he alone, or someone that he anointed could write his life story. Anyone else would have to pay $2 million dollars for daring to undertake the enterprise.

Getting sued by one of the most powerful men in the country—and one with mob connections—gets your attention. Fortunately, a national coalition of writers groups rose up to protest, claiming that Sinatra’s lawsuit against me was an assault upon all writers’ constitutionally protected freedoms of expression and should be dismissed on its face. In a joint statement they said: “The apparent goal behind Sinatra’s filing of this suit is to scare Ms. Kelley away from her investigation and, ultimately, to force her to scrap the book. Abuses of the judicial system such as these pose a serious threat to all writers.”

For one year, Sinatra pursued his lawsuit, but his allegations proved groundless, and he finally was forced to drop his case.

The writers groups applauded his action. “The court’s dismissal of this meritless suit—at the request of Mr. Sinatra—is a victory for all writers and the public,” stated their press release. “It reaffirms the right of the public to be informed about the lives of influential public persons whether or not they approve of the writer and his or her approach.”

The Baltimore Sun editorialized on the right to cover public figures without restriction: “If all the public can learn of the person is what the person himself wants it to learn, then our will become a very closed and ignorant society, unable to correct its ills, quite unlike what the drafters and subsequent generations of defenders of the free-speech First Amendment had in mind.”

I continued my work, interviewing Sinatra’s friends, employees, associates, former girl friends and lovers, federal law enforcement agents, plus musicians, movie stars and mobsters like Moe Dalitz, who had known and worked with him over the years. I also interviewed a few Sinatra relatives, including his son, Frank Sinatra, Jr. Through my years of research I received regular calls from Liz Smith, former New York Daily News gossip columnist, with all sorts of Sinatra stories, mostly scurrilous. Yet a few weeks before publication, Sinatra decided to make amends with the woman he demeaned on stage as “a dumpy, fat, ugly broad,” and referred to as “Lez” Smith. He invited her for drinks, she swooned, and Sinatra never had to read another negative word about himself in her columns.

My book was published in 1986 and enjoyed great success, selling over 1 million copies in hardback—a testament to the enduring fascination with Frank Sinatra. However, His Way was not applauded by the singer or his family, for the biography had opened doors that they had long kept locked.

Upon publication Nancy and Tina Sinatra called reporters to denounce the book and its author. Their father railed on television about “pimps and prostitutes” who write “a lot of crap” for money. “We nearly strangled on our pain and anger,” Nancy Sinatra said, reviling me as “the big C-word… I hate [Kitty Kelley]… If I ever met her, I don’t know what I’d do….” She ranted for months on her website and was still ranting years later when she tried to jump-start her career at the age of 54 by posing nude for Playboy. “Don’t ask me any questions about that goddamned Kitty Kelley or her goddamned book,” she warned reporters.

Tina Sinatra claimed that my biography had made her father ill, causing him to undergo major colon surgery in 1986 for seven and a half hours, and to endure a temporary colostomy. Tellingly, she waited until her father had died before she published her own book, which lacerated Barbara Sinatra, her father’s wife of 22 years, as a grasping, gold-digging wench not worthy of the family name. To this day the women speak only through lawyers.

Now that His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra is being published in trade paperback the alarms are once again clanging. “Take cover. Prepare for incoming,” warned one friend via e-mail. “Ole Blue Eyes might be gone but his daughters still prowl the forest.”

There is no longer any question about Frank Sinatra’s ties to the Mafia. As if to tease those mob connections, Nancy and Frank Sinatra, Jr. each appeared in different episodes of HBO’s The Sopranos. The producers of the hit series hung Frank Sinatra’s mug shot in Tony Soprano’s office at the Bada Bing. Yes, Ole Blue Eyes was once arrested on a morals charge and jailed for three days. (See pages 7-9 of His Way.) Movie directors continue to license his music as melodic striptease for their gangster films, and his picture inevitably appears in any film about the mafia.

My biography of Frank Sinatra is not paean to his music but rather an illumination of the man behind the music, who once described himself as “an 18-karat manic-depressive who lived a life of violent emotional contradictions with an over-acute capacity for sadness as well as happiness.”

Taking the man at his word I rode the roller coaster, and now a new generation of readers can join me for the ride.

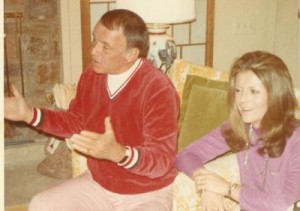

Photo: Kitty Kelley interviewing Frank Sinatra Jr. on January 15, 1983 in his suite at the Hyatt Regency Washington in Washington DC for His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra.

Cross-posted from Huffington Post