Gore Vidal

Dust to Dust

by Kitty Kelley

“Never offend an enemy in a small way,” Gore Vidal once wrote. The prickly writer, who thrived on making enemies, may soon be spewing venom from six feet under. Eight years after his death, he is scheduled to cast shade on his nemesis, William F. Buckley, Jr., in a new play by Alexandra Petri, called Inherit the Windbag. The play is in virtual rehearsals right now, at Washington, D.C.’s Mosaic Theatre Company, but when a stage version opens, likely next spring, the groundskeeper at Rock Creek Cemetery would be well advised to keep an eye on Section E, Lot 293 ½, where Vidal’s ashes are buried. Vidal outlived Buckley by four years, but never forgave the man who called him a “queer” in a 1968 televised debate. When Buckley died, Vidal cheered, “RIP WFB—in hell.”

The odyssey that Vidal’s remains took before their interment was no less dramatic. The writer spent many hours negotiating the details of his grave. From his villa in Ravello, Italy, he stipulated that his ashes be placed near an Augustus Saint-Gaudens sculpture commissioned by the historian Henry Adams, in memory of his wife, who committed suicide. This monument is the most visited site in the eighty-acre park, just across the street from the former Old Soldiers’ Home, where President Lincoln summered during the Civil War. Vidal, who made millions in real estate, understood its first three commandments: location, location, location.

details of his grave. From his villa in Ravello, Italy, he stipulated that his ashes be placed near an Augustus Saint-Gaudens sculpture commissioned by the historian Henry Adams, in memory of his wife, who committed suicide. This monument is the most visited site in the eighty-acre park, just across the street from the former Old Soldiers’ Home, where President Lincoln summered during the Civil War. Vidal, who made millions in real estate, understood its first three commandments: location, location, location.

Vidal also instructed that he and Howard Austen, his partner of fifty-three years, be buried near the grave of Jimmie Trimble, a blond athlete whom Vidal met when both were students at St. Albans School. Trimble was killed at Iwo Jima, but he lived for the rest of Vidal’s life in fevered fantasies. By placing his own remains between those of Trimble and Adams—a descendant of two American Presidents, who was buried next to his wife—Vidal was, as he wrote, “midway between heart and mind, to put it grandly.”

Like a pharaoh gilding his tomb, Vidal continued making legacy preparations: he commissioned his biography to be written in his lifetime by Fred Kaplan, who accompanied Vidal and Austen to the cemetery in 1994, to complete their final interment papers. Kaplan signed as their witness and later published a well-received book (Gore Vidal: A Biography), but, when the Times dismissed Vidal as a “minor” writer in its review, Vidal fired off a letter to the editor, blaming Kaplan. He claimed, preposterously, that he thought he’d commissioned the biographer Justin Kaplan, not Fred Kaplan. (Kaplan was not the only writer to be pulverized by Vidal. The three saddest words in the English language, Vidal once said, were “Joyce Carol Oates.”)

Not long after Kaplan finished the book, Vidal moved his papers (almost four hundred boxes’ worth) from the University of Wisconsin’s Center for Film and Theater Research to Harvard University. Months before he died, at the age of eighty-six, he added a codicil to his will, leaving his entire thirty-seven-million-dollar estate to Harvard, which triggered a blizzard of lawsuits after his death and delayed his burial for years. “At the end, Gore was drinking bottles of Macallan Scotch around the clock, having hallucinations, in and out of hospitals and well into dementia,” his half sister Nina Straight said. She was the first to sue the Vidal estate, to recover a million dollars that she said she had loaned her brother to fund his lawsuit against Buckley.

“The end was awful, just awful,” her son Burr Steers said. “He was no longer Gore—just a deranged old man, killing himself with booze.” Steers, who had taken possession of his uncle’s ashes, filed suit, too, claiming ownership of Vidal’s house in Los Angeles, which had been left to him in a previous will. Later, Steers sued to have the estate trustee, Andrew Auchincloss, his third cousin, removed for “reckless misconduct,” claiming that Auchincloss had tried to defraud him.

Vidal, who liked to say that, after fifty, litigation replaces sex, probably would have enjoyed the flurry of lawsuits. After numerous depositions and document dumps, Straight dropped her suit, Steers lost the L.A. house, and Auchincloss remained trustee of the estate. How the ashes made it from Los Angeles to Rock Creek Cemetery, where they were interred in 2016, in a small private ceremony, is a mystery. Steers’s attorney, Eric M. George, had no comment, citing “a strict confidentiality clause.” For someone who thrived on publicity to be buried with no fanfare seems pathetic, but a public Facebook page, GoreVidalNow.com, indicates that there is at least one keeper of the literary banshee’s flame. The site is managed by Michelle Gore, who is married to a third cousin of Vidal’s and who visited Vidal in Italy. “Gore, I miss you each day,” she writes. A sweet coda for a curmudgeon. ♦

Gore Vidal was interred in Rock Creek Cemetery on June 24, 2016 in a small private ceremony.

Posted by GoreVidalNow.com on Wednesday, July 20, 2016

Published in the print edition of the New Yorker, August 31, 2020 issue, with the headline “Dust to Dust.” Online “Can Gore Vidal Find Rest in His Final Resting Place?“

(See also “Gore Vidal’s Final Feud” by Kitty Kelley, Washingtoninan November 2015.)

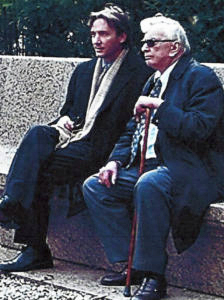

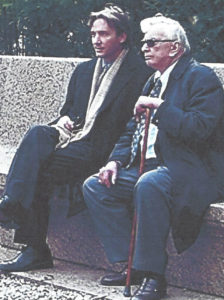

Photo of Gore Vidal with nephew Burr Steers in Rock Creek Cemetery courtesy of Burr Steers

Burying Gore Vidal

See Kitty Kelley’s “Gore Vidal’s Final Feud” in the November 2015 Washingtonian magazine for an account of the consternation caused by Vidal’s final disposition of his wealth and property: “Given his penchant for dissent Vidal–who died in 2012–would be smacking his lips to know that, between his death and this fall, there has been a bitter fight over his will pitting distant relatives against one another.”

Update 11/9/15: The article has been posted at the Washingtonian website here.

Photo: Gore Vidal with Burr Steers, son of Vidal’s half-sister Nina Auchincloss Straight.