General

A Trail of Tears and Triumph

by Kitty Kelley

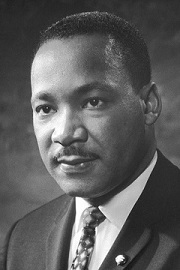

“April is the cruelest month,” wrote the poet T.S. Eliot, and for followers of Martin Luther King Jr., April 4, 1968, was the cruelest day. At 6:01 p.m. on that Thursday, the beloved preacher of nonviolence was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee.

“April is the cruelest month,” wrote the poet T.S. Eliot, and for followers of Martin Luther King Jr., April 4, 1968, was the cruelest day. At 6:01 p.m. on that Thursday, the beloved preacher of nonviolence was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee.

Hours later, riots erupted throughout the country as angry mobs smashed windows, trashed stores, and blew up cars, leaving dozens dead and more than 100 cities smoldering. President Lyndon Johnson finally summoned the National Guard to restore order.

More than five decades later, some scars remain, but Dr. King’s dream of a beloved community still shines, even in the poorest pockets of the country. I recently joined Stanford University’s “Following King: Atlanta to Memphis” tour, led by Professor Clayborne Carson, senior editor of The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Vols. I-VII. Traveling by bus for a week — masked, in the era of covid — we patronized only minority-owned hotels and restaurants.

We began in Atlanta with a visit to Dr. King’s last home, the one he purchased after winning the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize. We toured the National Center for Civil and Human Rights and learned from a freshman at Morehouse College why he values his education on the 61-acre campus of one of America’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU), which is close to Spelman College, an HBCU for women:

“We both fall under the umbrella of Atlanta University Center, so we can attend classes on either campus…Our slogan here at Morehouse is ‘Let There be Light,’ and while it’s prevalent in my generation [Class of 2025] not to speak your mind lest you be canceled, here, people are not making fun of you or out to cancel you. They tell us: ‘Say your ignorance in class so you don’t say it in the world.’”

Before leaving Atlanta, we visit the Ebenezer Baptist Church, the spiritual home of Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, where the Rev. Raphael G. Warnock now serves every Sunday as pastor. The rest of the week, he serves as Georgia’s junior senator in the U.S. Senate.

Boarding the bus, we headed for Montgomery, Alabama, home of the Confederacy, where we visit the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, created by Bryan Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), the nonprofit that guarantees the defense of any prisoner in Alabama sentenced to death. For many of us, this is the most upsetting museum on the tour because it forces you to see the terrible connection between 1865 and today.

The EJI has identified more than 4,000 Black men, women, and children who were lynched. At the site’s center hang 800 rusted steel monuments, one for each county in the U.S. where documented lynchings took place. Entering the museum, we were confronted with replicas of slave pens, where we saw and heard first-person accounts from enslaved people describing what it was like to be ripped from their families and await sale at the nearby auction block. We learned what “sold down the river” means: Many enslaved people were punished with a transfer from the North to harsher conditions in the South. Etched in bronze is Harriet Tubman’s quote, “Slavery is the next thing to hell.”

On a nearby street corner, we meet the artist Michelle Browder, who showed us her outdoor gallery honoring “Mothers of Gynecology”; her 15-foot-high sculptures depict three enslaved women subjected to brutal experiments for “supposed” medical advancement.

From Montgomery, we were bused to Birmingham (aka “Bombingham”) and the 16th Street Baptist Church, where four little girls were killed by a bomb as they prepared to sing in their choir on September 15, 1963. The pastor’s undelivered sermon that Sunday was entitled “A Love that Forgives.”

Weeks before, 300,000 people had gathered peacefully on the National Mall in Washington, DC, to hear Dr. King’s soaring “I Have a Dream” speech. Later, he was jailed in Alabama. While there, he wrote his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail” on scraps of paper and bits of toilet tissue that his lawyer smuggled out piece by piece on each visit. Dr. King’s message berated white moderates “devoted to order, not to justice,” particularly those white church leaders “more cautious than courageous.”

From Montgomery, we traveled to Selma to meet our no-nonsense guide in the projects. “We’re in the ‘hood now, so if you hear a pop-pop, duck,” she said. People on the bus squirmed as she delivered her blunt commentary:

“Selma is a city of barely 20,000, and 80 percent of us are African American, still living in the poorest wards…Voting registration has shrunk because folks ask, ‘What’s voting done for us?’ We’re a broken economy, a broken community…Hate groups study us as a failed model of Democratic policies.”

Rain fell as we walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, named for a Confederate general and Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan and the site of “Bloody Sunday,” March 7, 1965, when police attacked Civil Rights marchers with horses, clubs, and tear gas.

We later stopped in Meridian and Jackson, Mississippi, enroute to Memphis, where we visited the Lorraine Motel, with its white plastic wreath of blood red roses marking the spot on the second-floor balcony where Dr. King was assassinated. The plaque beneath reads:

“They said one to another,

Behold, here cometh the dreamer,

Let us slay him

And we shall see what will become of his dream.”

– Genesis 37.19-20

The motel site has been expanded into a complex of buildings incorporated as the National Civil Rights Museum in 1991, the first in the U.S. dedicated to telling the Black Civil Rights story. It’s also been called “The Conspiracy Museum” because its second floor, entitled “Lingering Questions,” chronicles the capture and arrest of James Earl Ray and explores myriad conjectures about whether Dr. King’s killer acted alone.

Outside on the street, a tiny woman named Jacqueline Smith protests the $27 million museum complex. She weighs no more than 90 pounds, but her outrage is ferocious. She’s been standing on the corner every day since 1988, when she was evicted from the motel to make way for the museum’s construction.

“What’s the point of all this?” she asks. “What does this rich museum offer the needy, the homeless, the poor, the hungry, the displaced, and the disadvantaged? Dr. King said: ‘Spend the necessary money to get rid of slums, eradicate poverty.’ This museum was built with non-unionized labor. Dr. King was all for unionized workers. This museum celebrates his murderer… does the John F. Kennedy Library celebrate Lee Harvey Oswald?”

Someone starts to speak, but Jackie brooks no interruption. “Why don’t you white people do what’s right for a change?”

Quietly, we return to our bus, edified by Dr. King’s vocal disciple.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

George Soros: A Life in Full

by Kitty Kelley

George Soros, now 91, cites 1944 as the best year of his life. He was 14 years old, living as a non-practicing Jew under the Nazis in Hungary, and hiding in various places throughout Budapest. His adored father had changed the family name from Schwartz to Soros, and moving from house to house, young George learned to cope with danger and live with risk.

George Soros, now 91, cites 1944 as the best year of his life. He was 14 years old, living as a non-practicing Jew under the Nazis in Hungary, and hiding in various places throughout Budapest. His adored father had changed the family name from Schwartz to Soros, and moving from house to house, young George learned to cope with danger and live with risk.

These early life lessons, plus an education at the London School of Economics, catapulted Soros into immense personal wealth as a financial analyst. Fluency in French, German, Hungarian, and English helped him master the international markets in which he accrued that wealth. His Quantum Fund — which made $5.5 billion in 2013 — became the most successful hedge fund in history. Yet, at the age of 49, Soros decided to stop making money and start giving it away instead. In 1979, he founded his Open Society Foundation and began rewriting the definition of global philanthropy. In doing so, he changed the world.

Ascending into the philanthropic strata of billionaires, Soros soon surpassed the largesse of Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Mellon, and even Bill and Melinda Gates, giving an estimated $35 billion to open up previously closed communist societies across Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.

It’s fascinating to read Peter L.W. Osnos’ George Soros: A Life in Full in 2022, as Vladimir Putin plunders Ukraine, and to realize how prescient Soros was in 1989 to foster openness in those former autocracies. Along with education for all, “We…need a market economy that protects minorities and we need the rule of law,” Soros has said. His foundation — which began by bankrolling a $100 million project to revive preschool education over five years — seeks to help our imperfect world achieve those very things.

Of course, closed societies don’t often enjoy being pried open, and Soros’ efforts were detested in nations where despots ruled and corruption festered, such as Angola, Suharto’s Indonesia, Peru, Zimbabwe, Malaysia, and Russia. In the past, Soros has also challenged Israel’s “racist and anti-democratic policies” and questioned whether that country is “really a democracy.” His support for progressive and liberal causes continues to make him a target of the political right, which demonizes him via anti-Semitic conspiracy theories.

In 1997, after endowing Central European University in Hungary with $880 million, Soros decided to bring his Open Society Foundation to the U.S. He began in Baltimore, where he instituted fellowship programs, community development initiatives, work development programs, and job markets. Today, his foundation funds more than $250 million a year in programs and grants across the country, but Baltimore remains the flagship of his American success.

To capture Soros’ life, editor Osnos employs an interesting subgenre of biography by assigning eight writers who’ve known the man at various stages in his life to present their impressions of this survivor, philanthropist, activist, global citizen, and all-around scourge of the far right. Osnos, who founded the publishing house PublicAffairs, explored the technique in 2000 when he assigned three journalists to write a book on Putin’s ascendance to the presidency of Russia.

Now, presumably, Osnos’ goal is to make the George Soros diamond sparkle in all its facets. Unfortunately, the editor fails to edit. Perhaps he’s reluctant because he’s self-publishing this book with his wife and states that the project “has been funded by a private equity that is backed by Soros’ wealth…That money will be repaid from revenues the book accrues.” Osnos arranged to distribute the book through Harvard Business Review Press “to assure the broadest possible reach for the book in the world marketplace.”

Caveat emptor.

Some chapters overlap, duplicate information, meander off subject, and layer the reader with lengthy opinions. Sebastian Mallaby’s chapter, “The Financier,” is best read by those holding a degree in economics, while Orville Schell’s “A Network of Networks” presents a mouth-watering account of “some of the most brilliant, accomplished and engaged people on the planet” invited for luxurious weekends at Chateau Soros, described as akin to “being summoned to the court of Louis XIV.”

The book’s best chapter by far is “Philanthropy with a Vision” by Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, whom Osnos introduces as “a black man and proudly gay.” Consequently, readers might expect to find something in Walker’s essay pertaining to his race and/or sexual identity. Here, the editor really ought to have edited himself because nothing in Walker’s cogent and erudite chapter reflects anything about either, only his shining admiration for a philanthropist dedicated to leaving the world a better place than he found it so many decades ago.

Thank you, Darren Walker, and God bless you, George Soros.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

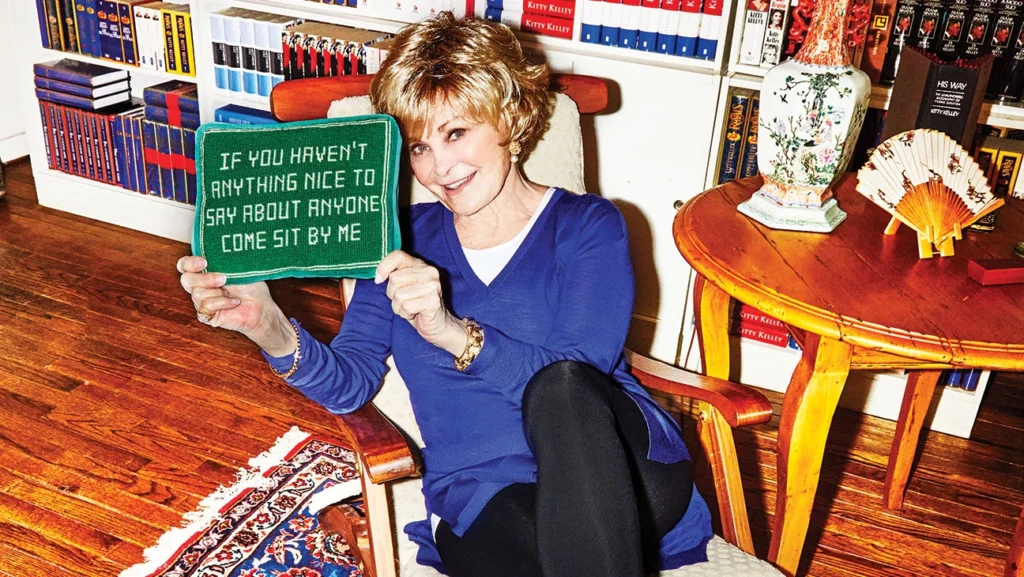

Queen of the Unauthorized Biography Spills Her Own Secrets

By Seth Abramovitch

There was, not that long ago, a name whose mere invocation could strike terror in the hearts of the most powerful figures in politics and entertainment.

That name was Kitty Kelley.

If it’s unfamiliar to you, ask your mother, who likely is in possession of one or more of Kelley’s best-selling biographies — exhaustive tomes that peer unflinchingly (and, many have claimed, nonfactually) into the personal lives of the most famous people on the planet.

“I’m afraid I’ve earned it,” sighs Kelley, 79, of her reputation as the undisputed Queen of the Unauthorized Biography. “And I wave the banner. I do. ‘Unauthorized’ does not mean untrue. It just means I went ahead without your permission.”

That she did. Jackie Onassis, Frank Sinatra, Nancy Reagan — the more sacred the cow, the more eager Kelley was to lead them to slaughter. In doing so, she amassed a list of enemies that would make a despot blush. As Milton Berle once cracked at a Friars Club roast, “Kitty Kelley wanted to be here tonight, but an hour ago she tried to start her car.”

Only a handful of contemporary authors have achieved the kind of brand recognition that Kelley has. At the height of her powers in the early 1990s, mentions of the ruthless journo with the cutesy name would pop up everywhere from late night monologues to the funny pages. (Fully capable of laughing at herself, her bathroom walls are covered in framed cartoons drawn at her expense.)

Kelley is hard to miss around Washington, D.C. She drives a fire-engine red Mercedes with vanity plates that read “MEOW.” The car was a gift from former Simon & Schuster chief Dick Snyder, who was determined to land Kelley’s Nancy Reagan biography.

“Simon & Schuster said, ‘Kitty, Dick really wants the book. What will it take to prove that?’ ” she recalls. “I said,  ‘A 560 SL Mercedes, bright red, Palomino interior.’ ‘We’ll be back to you.’ ” She insists she was only kidding. But a few days later, Kelley answered the phone and was directed to walk to the nearest corner: “Your bright red 560 SL is sitting there waiting for you.” Sure enough, there it was. The “MEOW” plates were a surprise gift from the boyfriend who would become her second husband, Dr. John Zucker.

‘A 560 SL Mercedes, bright red, Palomino interior.’ ‘We’ll be back to you.’ ” She insists she was only kidding. But a few days later, Kelley answered the phone and was directed to walk to the nearest corner: “Your bright red 560 SL is sitting there waiting for you.” Sure enough, there it was. The “MEOW” plates were a surprise gift from the boyfriend who would become her second husband, Dr. John Zucker.

Ask Kelley how many books she has sold, and she claims not to know the exact number. It is many, many millions. Her biggest sellers — 1986’s His Way, about Frank Sinatra, and 1991’s Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography, began with printings of a million each, which promptly sold out. “But they’ve gone to 12th printings, 14th printings,” she says. “I really couldn’t tell you how many I’ve sold in total.” She does recall first breaking into The New York Times‘ best-seller charts, with 1978’s Jackie Oh! “I remember the thrill of it. I remember how happy I was. It’s like being prom queen,” she says. “Which I actually was about 100 years ago.”

Regardless of one’s opinions about Kelley, or her methodology, there can be no denying that her brand of take-no-prisoners celebrity journalism — the kind that in 2022 bubbles up constantly in social media feeds in the form of TMZ headlines and gossipy tweets — was very much ahead of its time.

In fact, a detail from Kelley’s 1991 Nancy Reagan biography trended in December when Abby Shapiro, sister of conservative commentator Ben Shapiro, tweeted side-by-side photos of Madonna and the former first lady. “This is Madonna at 63. This is Nancy Reagan at 64. Trashy living vs. Classic living. Which version of yourself do you want to be?” read the caption. Someone replied with an excerpt from Kelley’s biography that described Reagan as being “renowned in Hollywood for performing oral sex” and “very popular on the MGM lot.” The excerpt went viral and launched a wave of memes. “It doesn’t fit with the public image. Does it? It just doesn’t. And the source on that was Peter Lawford,” says Kelley, clearly tickled that the detail had resurfaced.

While amplifying those kinds of rumors might not suggest it, in many eyes, Kelley is something of a glass-ceiling shatterer. “Back when she started in the 1970s, it was a largely male profession,” says Diane Kiesel, a friend of Kelley’s who is a judge on the New York Supreme Court. “She was a trailblazer. There weren’t women writing the kind of hard-hitting books she was writing. I’m sure most of her sources were men.”

But what of her methodology? Kelley insists she never sets out to write unauthorized biographies. Since Jackie Oh!, she has always begun her research by asking her subjects to participate, often multiple times. She is invariably turned down, then continues about the task anyway. She’s also known to lean toward blind sourcing and rely on notes, plus tapes and photographs, to back up the hundreds of interviews that go into every book.

“Recorders are so small today, but back then it was very hard to carry a clunky tape recorder around and slap it on the table in a restaurant and not have all of that ambient noise,” she says. To prove the conversations happened, Kelley devised a system in which she would type up a thank-you note containing the key details of their meeting — location, date and time — and mail it to every subject, keeping a copy for herself. If a subject ever denied having met with her, she would produce the notes from their conversation and her copy of the thank-you note.

So far, the system has worked. While many have tried to take her down, the ever-grinning Kelley has never been successfully sued by a source or subject.

Now 79, she lives in the same Georgetown townhouse she purchased with her $1.5 million advance (that’s $4 million adjusted for inflation) for His Way, which the crooner unsuccessfully sued to prevent from even being written.

Among the skeletons dug up by Kelley in that 600-page opus: that Ol’ Blue Eyes’ mother was known around  Hoboken, New Jersey, as “Hatpin Dolly” for a profitable side hustle performing illegal abortions. Sinatra’s daughter Nancy Sinatra said the family “strangled on our pain and anger” over the book’s release, while her sister, Tina, said it caused her father so much stress, it forced him to undergo a seven-and-a-half-hour surgical procedure on his colon.

Hoboken, New Jersey, as “Hatpin Dolly” for a profitable side hustle performing illegal abortions. Sinatra’s daughter Nancy Sinatra said the family “strangled on our pain and anger” over the book’s release, while her sister, Tina, said it caused her father so much stress, it forced him to undergo a seven-and-a-half-hour surgical procedure on his colon.

Giggly, vivacious and 5-foot-3, Kelley presents more like a kindly neighbor bearing blueberry muffins than the most infamous poison-pen author of the 20th century. “I seem to be doing more book reviewing than book writing these days,” she says in one of our first correspondences and points me to a review of a John Lewis biography published in the Washington Independent Review of Books.

She has not tackled a major work since 2010’s Oprah — a biography of Oprah Winfrey touted ahead of its release by The New Yorker as “one of those King Kong vs. Godzilla events in celebrity culture” but which fizzled in the marketplace, barely moving 300,000 copies. Among its allegations: that Winfrey had an affair early in her career with John Tesh — of Entertainment Tonight fame — and that, according to a cousin, the talk show host exaggerated tales of childhood poverty because “the truth is boring.”

“We had a falling out because I didn’t want to publish the Oprah book,” says Stephen Rubin, a consulting publisher at Simon & Schuster who grew close to Kelley while working with her at Doubleday on 2004’s The Family: The Real Story of the Bush Dynasty.

“I told her that audience doesn’t want to read a negative book about Saint Oprah. I don’t think it’s something she should have even undertaken. We have chosen to disagree about that.”

The book ended up at Crown. It would be nine months before Kelley would speak to Rubin again. They’ve since reconciled. “She’s no fun when she’s pissed,” Rubin notes.

Adds Kelley of Winfrey’s reaction to the book: “She wasn’t happy with it. Nobody’s happy with [an unauthorized] biography. She was especially outraged about her father’s interview.” She is referencing a conversation she had, on the record, with Winfrey’s father, Vernon Winfrey, in which he confirmed the birth of her son, who arrived prematurely and died shortly after birth.

But Kelley says the backlash to Oprah: A Biography and the book’s underwhelming sales had nothing to do with why she hasn’t undertaken a biography since. Rather, her husband, a famed allergist in the D.C. area who’d give a daily pollen report on television and radio, died suddenly in 2011 of a heart attack. “John was the great love of her life,” says Rubin. “He was an irresistible guy — smart, good-looking, funny and mad for Kitty.”

“Boy, I was knocked on my heels,” she says of Zucker’s death. “He hated the cold weather. He insisted we go out to the California desert. We were in the desert, and he died at the pool suddenly. I can’t account for a couple of years after that. It was a body blow. I just haven’t tackled another biography since.”

A decade having passed, Kelley does not rule out writing another one — she just hasn’t yet found a subject worthy of her time. “I can’t think of anyone right now who I would give three or four years of my life to,” Kelley says. “It’s like a college education.”

For fun, I throw out a name: Donald Trump. Kelley shakes her head vigorously. “I started each book with real respect for each of my subjects,” she says. “And not just for who they were but for what they had accomplished and the imprint that they had left on society. I can’t say the same thing about Donald Trump. I would not want to wrap myself in a negative project for four years.”

“You know,” I interrupt, “I’m imagining people reading that quote and saying, ‘Well, you took ostensibly positive topics and turned them into negative topics.’ How would you respond to that?”

“I would say you’re wrong,” Kelley replies. “That’s what I would say. I think if you pick up, I don’t know — the Frank Sinatra book, Jackie Oh!, the Bush book — yes, you’re going to see the negatives and the positives, which we all have. But I think you’ll come out liking them. I mean, we don’t expect perfection in the people around us, but we seem to demand it in our stars. And yet, they’re hardly paragons. Each book that I’ve written was a challenge. But I would think that if you read the book, you’re going to come out — no matter what they say about the author — you’re going to come out liking the subject.”

***

Kelley arrived in the nation’s capital in 1964. She was 22 and, through the connections of her dad, a powerful attorney from Spokane, Washington, she landed an assistant job in Democratic Sen. Eugene McCarthy’s office. She worked there for four years, culminating in McCarthy’s 1968 presidential bid. It was a tumultuous time. McCarthy’s Democratic rival, Robert F. Kennedy, was gunned down in Los Angeles at a California primary victory party on June 5. When Hubert Humphrey clinched the nomination that August amid the DNC riots in Chicago, Kelley’s dreams of a future in a McCarthy White House were dashed, and she decided a life in politics was not for her.

“But I remain political,” Kelley clarifies. “I am committed to politics and have been ever since I worked for Gene McCarthy. I was against the war in Vietnam. I don’t come from that world. I come from a rich, right-wing Republican family. My siblings avoid talking politics with me.”

In 1970, she applied for a researcher opening in the op-ed section at The Washington Post. “It was a wonderful job,” she recalls. “I’d go into editorial page conferences. And whatever the writers would be writing, I would try and get research for them. Ben Bradlee’s office was right next to the editorial page offices. And if he had both doors open, I would walk across his office. He was always yelling at me for doing it.”

According to her own unauthorized biography — 1991’s Poison Pen, by George Carpozi Jr. — Kelley was fired for taking too many notes in those meetings, raising red flags for Bradlee, who suspected she might be researching a book about the paper’s publisher, Katharine Graham. Kelley says the story is not true.

“I have not heard that theory, but I will tell you I loved Katharine Graham, and when I left the Post, she gave me a gift. She dressed beautifully, and when the style went from mini to maxi skirts —because she was tall and I am not, I remember saying, ‘Mrs. Graham, you’re going to have to go to maxis now. And who’s going to get your minis?’ She laughed. It was very impudent. But then I was handed a great big box with four fabulous outfits in them — her miniskirts.”

Kelley says she left the Post after two years to pursue writing books and freelancing. She scored one of the bigger scoops of 1974 when the youngest member of the upper house — newly elected Democratic Sen. Joe Biden of Delaware, then 31 — agreed to be profiled for Washingtonian, a new Beltway magazine.

Biden was still very much in mourning for his wife and young daughter, killed by a hay truck while on their way to buy a Christmas tree in Delaware on Dec. 18, 1972. The future president’s two young sons, Beau and Hunter, survived the wreck; Biden was sworn into the Senate at their hospital bedsides.

After the accident, Biden developed an almost antagonistic relationship to the press. But his team eventually softened him to the idea of speaking to the media. That was precisely when Kelley made her ask.

Biden would come to deeply regret the decision. The piece, “Death and the All-American Boy,” published on June 1, 1974, was a mix of flattery (Kelley writes that Biden “reeks of decency” and “looks like Robert Redford’s Great Gatsby”), controversy (she references a joke told by Biden with “an antisemitic punchline”) and, at least in Biden’s eyes, more than a little bad taste.

The piece opens: “Joseph Robinette Biden, the 31-year-old Democrat from Delaware, is the youngest man in the Senate, which makes him a celebrity of sorts. But there’s something else that makes him good copy: Shortly after his election in November 1972 his wife Neilia and infant daughter were killed in a car accident.”

Later, Kelley writes, “His Senate suite looks like a shrine. A large photograph of Neilia’s tombstone hangs in the inner office; her pictures cover every wall. A framed copy of Milton’s sonnet ‘On His Deceased Wife’ stands next to a print of Byron’s ‘She Walks in Beauty.’ “

But it was one of Biden’s own quotes that most incensed the future president.

She writes: ” ‘Let me show you my favorite picture of her,’ he says, holding up a snapshot of Neilia in a bikini. ‘She had the best body of any woman I ever saw. She looks better than a Playboy bunny, doesn’t she?’ “

“I stand by everything in the piece,” says Kelley. “I’m sorry he was so upset. And it’s ironic, too, because I’m one of his biggest supporters. It was 48 years ago. I would hope we’ve both grown. Maybe he expected me to edit out [the line about the bikini], but it was not off the record.” Still, she admits her editor, Jack Limpert, went too far with the headline: “I had nothing to do with that. I was stunned by the headline. ‘Death and the All-American Boy.’ Seriously?”

It would be 15 years before Biden gave another interview, this time to the Washington Post‘s Lois Romano during his first presidential bid, in 1987. Biden, by then remarried to Jill Biden, recalled to Romano, “[Kelley] sat there and cried at my desk. I found myself consoling her, saying, ‘Don’t worry. It’s OK. I’m doing fine.’ I was such a sucker.”

Kelley’s first book wasn’t a biography at all. “It was a book on fat farms,” she says, which was based on a popular article she’d written for Washington Star News on San Diego’s Golden Door — one of the country’s first luxury spas catering to celebrity clientele like Natalie Wood, Elizabeth Taylor and Zsa Zsa Gabor.

“On about the third day, the chef came out, and he said, ‘Would you like a little something?’ ” says Kelley. “He was Italian. I said, ‘Yes, I’m so hungry.’ And he kind of laughed. Turns out he wasn’t talking about tuna fish. I said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me.’ He said, ‘I have sex all the time with the people here.’ I said, ‘I should tell you, I’m here writing a book.’ He said, ‘I’ll tell you everything!’ I warned him, ‘OK — but I’m going to use names.’ And I did.”

The book, a 1975 paperback called The Glamour Spas, sold “14 copies, all of them bought by my mother,” she says. But the publisher, Lyle Stuart, dubbed in a 1969 New York Times profile as the “bad boy of publishing,” was impressed enough with Kelley’s writing that he hired her in 1976 to write a biography of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

The crown jewel of the book that would become Jackie Oh! was Kelley’s interview with Sen. George Smathers, a Florida Democrat and John F. Kennedy’s confidant. (After they entered Congress the same year and quickly became close friends, Kennedy asked Smathers to deliver two significant speeches: at his 1953 wedding and his 1960 DNC nomination.)

“It was quite explosive,” Kelley recalls of her three-hour dinner with Smathers. “He was very charming, very Southern and funny. And he said, ‘Oh, Jack, he just loved women.’ And he went on talking, and he said, ‘He’d get on top of them, just like a rooster with a hen.’ I said, ‘Senator, I’m sorry, but how would you know that unless you were in the room?’ He said, ‘Well, of course I was in the room. Jack loved doing it in front of people.’

“The senator, to his everlasting credit, did not deny it,” Kelley continues. “A reporter asked him, ‘Did you really say those things?’ And the senator replied, ‘Yeah, I did. I think I was just run over by a dumb-looking blonde.’ “

She followed that one, which landed on the New York Times best-seller list, with 1981’s Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star, which underwhelmed. Her next two, however — His Way and Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography (for which she earned a $3.5 million advance, $9 million in 2022 adjusted for inflation) — were best-sellers, moving more than 1 million copies each in hardcover.

She followed that one, which landed on the New York Times best-seller list, with 1981’s Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star, which underwhelmed. Her next two, however — His Way and Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography (for which she earned a $3.5 million advance, $9 million in 2022 adjusted for inflation) — were best-sellers, moving more than 1 million copies each in hardcover.

Her 1997 royal family exposé, The Royals — which presaged The Crown, the Lady Di renaissance and Megxit mania by several decades — contained allegations that the British royal family had obfuscated their German ancestry.

“Sinatra was huge and Nancy was huge, but The Royals gave me more foreign sales than I’ve ever had on any book,” Kelley beams, adding that the recent headlines about Prince Andrew settling with a woman who accused him of raping her as a teenager at Jeffrey Epstein’s compound “really shows the rotten underbelly of the monarchy, in that someone would be so indulged, really ruined as a person, without much purpose in life.”

“Looking around,” I ask Kelley, “is society in decline?”

“What a question,” she replies. “Let’s say it’s being stressed on all sides. I think it’s become hard to find people that we can look up to — those you can turn to to find your better self. We used to do that with movie stars. People do it with monarchy. Unfortunately, there are people like Kitty Kelley around who will take us behind the curtain.”

Contrary to her public persona, Kelley is known in D.C. social circles for her gentility. Judge Kiesel, a part-time author, first met her eight years ago when Kelley hosted a reception for members of the Biographers International Organization at her home.

“What amazed me was she was such the epitome of Southern hospitality, even though she isn’t from the South,” says Kiesel. “I remember her standing on the front porch of her beautiful home in Georgetown and personally greeting every member of this group who had showed up. There had to be close to 200 of us.”

Kelley hosts regular dinner parties of six to 10 people. “She likes to mix people from publishing, politics and the law,” says Kiesel. When Kiesel, who lives in New York City, needed to spend more time in D.C. caring for a sister diagnosed with cancer, Kelley insisted she stay at her home. “She threw a little dinner party in my honor,” Kiesel recalls. “I said, ‘Kitty — why are you doing this?’ She said, ‘You’re going to have a really rough couple of months and I wanted to show you that I’m going to be there for you.’ People look at her as this tough-as-nails, no-holds-barred writer — but she’s a very kind, sweet, generous woman.”

For Kelley, life has grown pretty quiet the past few years: “It’s such a solitary life as a writer. The pandemic has turned life into a monastery.” Asked whether she dates, she lets out a high-pitched chortle. “Yes,” she says. “When asked. No one serious right now. Hope springs eternal!”

I ask her if there is anything she’s written she wishes she could take back. “Do I stand by everything I wrote? Yes. I do. Because I’ve been lawyered to the gills. I’ve had to produce tapes, letters, photographs,” she says, then adds, “But I do regret it if it really brought pain.”

Says Rubin: “People think she’s a bottom-feeder kind of writer, and that’s totally wrong. She’s a scrupulous journalist who writes no-holds-barred books. They’re brilliantly reported.”

Before I bid her adieu, I can’t resist throwing out one more potential subject for a future Kelley page-turner.

“What about Jeff Bezos?” I say.

She pauses to consider, and you can practically hear the gears revving up again.

“I think he’s quite admirable,” she says. “First of all, he saved The Washington Post. God love him for that. And he took on someone who threatened to blackmail him. He stood up to it. I think there’s much to admire and respect in Jeff Bezos. He sounds like he comes from the most supportive parents in the world. You don’t always find that with people who are so successful.”

“So,” I say. “You think you have another one in you?”

“I hope so,” Kelley says. “I know you’re going to end this article by saying … ‘Look out!’ “

This story first appeared in the March 2 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine.

https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/lifestyle/arts/kitty-kelley-interview-unauthorized-biographies-1235101933/

Photo credits: top of page, Amy Lombard; Kitty Kelley in Merc, Amy Lombard; Kitty Kelly with His Way, Bettmann/Getty Images; Kitty Kelley with Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star, Harry Hamburg/NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images

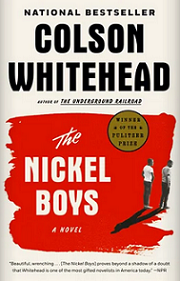

The Nickel Boys

by Kitty Kelley

Colson Whitehead is to American literature what the Rolls-Royce is to automobiles: revered and unrivaled. Having published eight novels, two books of nonfiction, and numerous essays and short stories, the 52-year-old writer has won a MacArthur “genius” grant, a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Booker Prize, the National Book Award, two Pulitzers, and the Carnegie Medal for Excellence, as well as a Whiting Writers Award, the John Dos Passos Prize for Literature, and a fellowship at the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers. In addition, he made the cover of TIME in 2019 as “America’s Storyteller.”

Colson Whitehead is to American literature what the Rolls-Royce is to automobiles: revered and unrivaled. Having published eight novels, two books of nonfiction, and numerous essays and short stories, the 52-year-old writer has won a MacArthur “genius” grant, a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Booker Prize, the National Book Award, two Pulitzers, and the Carnegie Medal for Excellence, as well as a Whiting Writers Award, the John Dos Passos Prize for Literature, and a fellowship at the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers. In addition, he made the cover of TIME in 2019 as “America’s Storyteller.”

The only accolade remaining seems to be a royal summons to Sweden for the Nobel.

In 2016, Whitehead’s eighth novel, The Underground Railroad, an allegorical tour de force about enslaved people trying to escape to freedom, thundered him to commercial success and sold over 1 million copies. He’d already started writing his next novel when he spotted a story in the Tampa Bay Times about the Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys in the Florida Panhandle. The segregated reform school, which opened in 1900, had finally closed in 2011.

Whitehead had never heard of the facility and was stunned to read that forensic archaeologists from the University of South Florida had discovered the unmarked graves of more than 50 African American boys on the property.

He realized then that if there was one adolescent abattoir like Dozier, “There were hundreds of others scattered across the land like pain factories,” he told the New York Times. “The survivors are never heard from and the guilty are never punished…They live to a ripe old age while their victims are damaged for life.”

The injustice rankled the author, and the subject became more urgent to Whitehead after the 2016 presidential election. Setting aside his novel-in-progress, he began investigating like the journalist he’d been at the Village Voice following his graduation from Harvard. He absorbed all the blood-stained facts surrounding the Dozier atrocity; he read reports, records, and forensic studies of the gravesites, plus accounts of solitary confinement during which Black and white boys were shackled by leg irons soldered to the floor and forced to live in their own excrement.

Many of these boys were also whipped by a three-foot-long strap called Black Beauty. Those who did not survive were dumped into dirt holes; those who did were forever haunted. They became men “with wives and ex-wives and children they did and didn’t talk to…dead in prison or decomposing in rooms they rented by the week.”

After mastering the grisly facts, the spectacular novelist within Whitehead took flight with The Nickel Boys. In this spare book — it’s just 224 pages — he bestows humanity on the unnamed victims who’d once been sodomized and beaten witless. He humanizes them in the character Elwood Curtis, an orphan who lives with his grandmother, Harriet. She toils as a cleaning lady and sleeps with a “sugarcane machete under her pillow for intruders.”

One Christmas, Harriet gives Elwood his greatest treasure: the 1962 LP “Martin Luther King at Zion Hill,” the only record he’s allowed to play. Elwood listens to the album every day and long into the night. He embraces Dr. King’s words as his guidepost for living. He believes that the long arc of the moral universe is bending towards him and will soon change his life.

That, it does — tragically.

Through no fault of his own, Elwood ends up in the hellscape of Nickel Academy, where he meets his polar opposite, a street-smart tough named Turner who thinks Elwood is hopelessly naïve. The story turns on their relationship, their joint attempt at escape, and the final honor one pays to the other.

Nickel is not Father Flanagan’s Boys Town, where “He ain’t heavy, Father. He’s my brother” was the motto. Instead, among Nickel survivors, there’s a bond of grievous horror and lives never lived:

“[They] could have been many things had they not been ruined by that place…not all of them were geniuses…but they had been denied even the simple pleasure of being ordinary. Hobbled and handicapped before the race even began, never figuring out how to be normal.”

For them, the long arc of the moral universe was forever out of reach.

The Nickel Boys is a novel that elevates Colson Whitehead to the pantheon alongside Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, and Zora Neale Hurston, all of whom, too, bore witness to America’s pernicious legacy of racism and white supremacy.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Home/Land

by Kitty Kelley

Upon his death in 1938, Thomas Wolfe bequeathed to America’s literary canon a 1,100-page manuscript which, published posthumously, trumpeted a universal truth: “You can’t go home again.” Rebecca Mead now challenges the bard of Asheville, North Carolina, with her third book, Home/Land: A Memoir of Departure and Return.

Upon his death in 1938, Thomas Wolfe bequeathed to America’s literary canon a 1,100-page manuscript which, published posthumously, trumpeted a universal truth: “You can’t go home again.” Rebecca Mead now challenges the bard of Asheville, North Carolina, with her third book, Home/Land: A Memoir of Departure and Return.

A British subject who graduated from Oxford, Mead emigrated to the U.S. in 1988 on a student visa to do graduate work at New York University and stayed for 30 years. She lived in Manhattan, endured numerous cycles of “falling in love, being in love and falling out of love.” Then she met her husband, also a writer, moved to Brooklyn, had a child, and, in 2011, became an American citizen. But she did not live happily ever after.

Mead grew increasingly dismayed over Brooklyn’s urban development of rising towers that encroached on her sylvan view: “Birnam Wood was coming to Dunsinane, I thought.” Worse was the right-wing clamor of the Tea Party that arose in the wake of Barack Obama’s election. Then came a nationalistic rhetoric that spread like gangrene. Finally, roiled by dystopian fears of Donald Trump, Mead and her husband decided to flee Dunsinane with their young son. They packed 170 boxes of books and flew first class to the U.K. on one-way tickets.

Months later, in 2018, Mead, a correspondent for the New Yorker, wrote an article about her repatriation, “A New Citizen Decides to Leave the Tumult of Trump’s America.” She seemed to be road-testing the idea of a future book on “the wrenching choice to return to Britain.” In her essay, she admitted that going home was not ideal:

“London is not a utopia; housing, in particular, is debilitatingly expensive…I am under no illusions that the U.K. is a beacon of progressivism. This is a move from the fire into the frying pan at best.”

Four years later, Home/Land reflects on that frying pan and its cost in terms of adjustment and accommodation. In his British elementary school, her Brooklyn-born son observes, “Everyone is so white.”

Much of what besets the U.S. — political turbulence, gun and gang violence, and immigration issues exacerbated by the pandemic — bedevils the U.K., too, but on a much smaller scale, which provides Mead with a sense of security.

Her regrets? Her reliefs? These questions, and more, are asked and answered in penetrating detail by a writer who pans for gold and presents it many times, albeit in sentences that are long and somewhat convoluted. For example, when Mead discovers that her father, as a child, lived in London’s Camden Square, where she now lives, she writes:

“And so, as I’d stepped onto the roof deck from the bedroom of the new house the realtor took me to — fantasizing a life in which I’d emerge in the morning with a cup of coffee in my hand and survey the landscape of narrow gardens and the backs of houses before descending to spend the day at my desk — I’d unwittingly been looking directly across at windows from which my father had surely looked out as a young boy in the arms of his mother.”

She continues, “To me this collision of the past and the present of Camden Square — the invisible tracery in which the threads of my father’s life and mine have against all odds, crossed and interwoven — is charged, if not exactly with meaning, then with wonder.”

Mead enumerates the benefits of trading a noisy, jangled democracy in the U.S. for a quieter life in an island nation about to experience the upset of Brexit, which she predicts will be “dark and chaotic.” For her, Britain’s advantages appear to be free healthcare, remarkably efficient public transportation, and college tuition capped at $12,000 a year (in the U.S., it can run more than $60,000 annually).

She feels the move across the pond gives her son a larger periscope on the world, and better positions her to cover international stories for the New Yorker, as was evidenced by her recent trip to Pompeii to profile the excavation of the 79 A.D. ruins from Mount Vesuvius. “I can get on a train…in the morning and be in Amsterdam by early afternoon, having traveled through four countries before lunchtime.”

Home/Land reads like a polyglot of personal diary and literary travelogue in which a writer meanders back and forth between her youth in America, including “years of psychotherapy,” and her present life in Britain as a woman of 56, an age at which, she bemoans, she feels invisible. Mead delves into the personal by discussing menopause and her humiliation over having hot flashes and experiencing changes in her brain chemistry.

Like an archeologist, she leads readers on a literary dig across London, over the open fields of Hampstead Heath, and into Fort Greene Park to discover a mound known as Boadicea’s Grave, named for an ancient British queen. The scholar in Mead instructs readers about the monarch now known as Boudicea and her bloody uprising in 60 A.D., adding parenthetically that “the root of ‘Boudica’ is the Celtic word for victory.” For those itching to return to the present, Mead first insists on more information about the victorious Queen Boadicea as celebrated in a 19th-century poem by Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

She then segues into Iron Age forts like Maiden Castle, where she informs readers that “ancient Britons built concentric rings of ditches and rises upon the slopes of a high saddle-backed hill, with labyrinth entry points so that when it is seen in aerial photographs the site resembles the maze toy my son once had, a wooden disk cut with circular grooves through which he tipped and twisted a steel ball bearing.” (See the warning above about lengthy sentences.)

Like any British memoirist born “lower middle class,” she also examines her country’s punishing class system and rightly applauds the state-subsidized education inaugurated in the 1980s as “the most important engine of social mobility.”

Rebecca Mead then ends her book like a pilgrim, still seeking to find her place in her new homeland.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Just Pursuit

by Kitty Kelly

With the publication of Just Pursuit, Laura Coates takes her place in a pantheon with Frank Serpico, who blew the whistle on police corruption in the 1970s. A former detective with the New York Police Department, Serpico’s public testimony led to the Knapp Commission and massive police reforms. But, as Coates writes in her second book, the corruption continues, poisoning every part of the justice system.

With the publication of Just Pursuit, Laura Coates takes her place in a pantheon with Frank Serpico, who blew the whistle on police corruption in the 1970s. A former detective with the New York Police Department, Serpico’s public testimony led to the Knapp Commission and massive police reforms. But, as Coates writes in her second book, the corruption continues, poisoning every part of the justice system.

Serpico’s exposé led to a bestselling book and a film starring Al Pacino, as well as a TV series and a documentary. Five decades later, Coates’ Just Pursuit carries that same commercial potential as it exposes lazy lawyers, preening prosecutors, cynical cops, and judges who preside over their courtrooms like tin-horn dictators, leaving in their wake an outsized number of poor, Black people forced to stand before them.

Citing one particularly egregious example, Coates writes about a white female judge who used her time on the bench to shop a website for boots rather than listen to the young Black adolescent before her testifying about the sexual abuse she suffered for years at the hands of her mother’s live-in boyfriend.

“Skipping down the center aisle, [the youngster approached] the witness stand in an above-the-knee skirt, breasts bouncing unrestrained,” writes Coates. “She giggled as she raised her right hand…She tugged at her skirt…the skirt buckled along her hips, slightly twisting her zipper…she slouched and tugged again at her skirt on one side…She rubbed her glossed lips together.”

Immediately, Coates knows the case is lost. “The judge’s focused glare on the child’s appearance said everything,” she writes. Still, Coates hopes she’s wrong, staying in the courtroom to find out. Sadly, the judge meets Coates’ expectations and lacerates the victim: “No one who has been raped, even a young teenager, would have skipped down the aisle of the courtroom dressed like that…her clothes were ill-fitting and she was not even wearing the appropriate undergarments, not even tights.”

Coates hung her head in sorrow, “unable to watch this child try to understand what about herself had warranted such contempt.”

Not every one of the 15 chapters in this book is equally weighted but each carries the heavy load of racism that Coates saw during her seven years as an attorney in the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice. Writing with verve and style, she relates her experience as a poll watcher in “a small town somewhere in Mississippi” during Obama’s second presidential campaign.

“The Deep South made me nervous,” Coates admits, as she walked into the same territory where the KKK once bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church, killing four young Black girls attending Sunday school; where Civil Rights activist Medgar Evers was assassinated; and where 14-year-old Emmett Till was murdered for allegedly whistling at a white woman. A Black female poll watcher in Mississippi, even in the 21st century, must feel like a Bengal tiger walking into a gun store.

It’s unnerving to read about the precautions Coates felt she had to take to be safe on that trip. Pulling into a sit-down restaurant, she scans the menu “to find whatever food would easily show if someone tampered with it. Nothing with gravy or sauce or anything else that covers someone’s spit under a bun. Something fried, served so hot it would kill the bacteria, was always the best option.” At the hotel, she elects to take the elevator a few floors. “I didn’t want to risk getting trapped in the stairs.”

In some chapters, Just Pursuit reads like a personal diary, such as when mother-to-be Coates experiences her first pregnancy. Walking into a courtroom to try a case, she stops to take a call from her OB-GYN, who tells her that tests show the fetus has an elevated alpha‑fetoprotein level, indicating spina bifida.

Coates tries to steady herself. “Don’t worry,” says the physician. “You’re still within the range to terminate your pregnancy. You want to call me after your trial? We can talk more then.” Raw and vulnerable, Coates lashes out. “Do you have any idea how heartless that just was? Why would you tell me that news in that way?”

“I didn’t mean to offend you,” the physician apologizes. “I just knew you didn’t have much time and you always seem so matter-of-fact.” Up to this point in the book, the doctor is correct: Coates has presented herself as she now appears on CNN — head-of-the-class smart and tensile tough, with a bit of suffer-no-fools impatience. At that time, though, you could almost hear her echo Sojourner Truth’s lament: “Ain’t I a woman?”

Coates does not reveal how she resolved that first pregnancy, but in later chapters, she discusses giving birth to her son and being pregnant again with a daughter. Nursing mothers who work (and their husbands) will relate to her various mentions of “pumping” and “keeping at least five full bottles [of milk] during my workday” and “drinking water incessantly to keep up with my milk supply.”

Having children seems to have changed the hard-charging prosecutor. “When I first became a prosecutor, I had thought each case could represent a dot on the arc that Dr. King hoped would bend toward justice,” she writes. “Now, I wondered if I was bending the arc of justice or breaking it, and I was afraid the justice system might just break me.”

Nor does she look back on her years of public service with pride:

“[T]he collective memories of trauma are so overwhelming that I fear I might lose myself if I don’t fill my time. The violence didn’t happen to me. But it…eviscerated me…and I still grapple with the scars of secondary trauma.”

Laura Coates once believed that justice was binary, achievable, and universally understood. No longer. Her experience has shown her a grotesque, twisted system corrupted by racism that needs to be reformed. She offers no solutions, but she supports her premise in horrific detail: “[T]he pursuit of justice creates injustice.”

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Manifesto

by Kitty Kelley

If “perseverance is genius in disguise,” then Bernardine Evaristo is a 22-carat gold, diamond-encrusted genius. She is the patron saint of persistence and proves it with her ninth book, Manifesto: On Never Giving Up. Having received the 2019 Booker Prize for her novel Girl, Woman, Other, Evaristo was the first Black woman and the first Black Brit to win the prize in its 50-year history. So she now has a global audience for her gospel on persevering.

If “perseverance is genius in disguise,” then Bernardine Evaristo is a 22-carat gold, diamond-encrusted genius. She is the patron saint of persistence and proves it with her ninth book, Manifesto: On Never Giving Up. Having received the 2019 Booker Prize for her novel Girl, Woman, Other, Evaristo was the first Black woman and the first Black Brit to win the prize in its 50-year history. So she now has a global audience for her gospel on persevering.

In this Manifesto, she offers insights into her biracial heritage (white English mother and Black Nigerian father), her “lower class” childhood (number four of eight children) in London, where she was considered by the British class system to be “inferior, marginal, negligible,” and her personal relationships (10 years living as a lesbian followed by a heterosexual marriage).

Whether homosexual or hetero, she was always a feminist and approached her struggle for success with a winning strategy: persistence — no matter what. “I’ve always felt myself to have an inner strength, by which I mean that I’m not needy or clingy. I don’t crave approval all the time…a tough inner core has been essential to my creative survival.”

In a chapter entitled “The women and men who came and went,” Evaristo expends several pages on what she calls her “lesbian era,” because she feels the problem is not with same-sex attraction but with a homophobic society that requires queer people to justify their existence. “Put it this way: my lesbian identity was the stuffing in a heterosexual sandwich.” In 2005, on a dating website, she met her husband, whom she describes as “a white middle-class man.” She portrays their marriage as a life preserver that freed her to get on with her most important work — writing.

Readers might wince as they read of Evaristo growing up Catholic, biracial, and brown-skinned in an overwhelmingly white Protestant area, enduring the name-calling of neighbors and the dismissals of the “unholy men…the half-drunk priests” who heard her confession every week:

“In my family, we had no doubts about the hypocrisy of the Catholic clergy, and as we each reached the age of fifteen, after ten years of attending Sunday Mass, my siblings and I were given the choice whether to continue or not. One by one we left the church never to return; as did my mother in due course.”

Evaristo began her creative journey by writing poetry; after college, she started writing and acting in the Theater of Black Women, Britain’s first such company. To survive, she lived on the dole and by her wits:

“I moved into slummy old properties, ready for demolition…A futon served as both sofa and bed. Boxes for clothes. Planks of wood and bricks became a bookcase…I prided myself of being able to stuff the rest of my meager possessions — clothes, books, bedding, kitchen utensils — into a few black rubbish bags.”

Leaving the theater in her 30s, Evaristo concentrated her creative energies on writing with London as her muse, having lived so many years in the city’s various districts. Finally, at the age of 55, she bound herself to a mortgage and settled into a life of writing, writing, writing. “I had become unstoppable with my creativity…writing became my permanent home.”

Now 62, Evaristo is unsparing about her own racism. As a child, she was ashamed of her father’s very dark skin. “I remember crossing the road when I saw him walking towards me. It was internalized racism, pure and simple…Black was bad and white was good. As a child I’d have killed to be white, with long blonde hair.”

She addresses “colorism or shadism,” and notes that, “sadly,” some people choose to pass because they’re light enough to be racialized as white, such as the Hollywood stars Carol Channing and Merle Oberon.

Throughout her life, Evaristo believed in herself and her talent, even when others did not. “[This] self-belief…is the single most important thing a writer needs, especially when the encouragement we crave from others is not forthcoming.”

The last section of her book, entitled “The self, ambition, transformation, activism,” echoes the principles of Psycho-Cybernetics by Maxwell Maltz, M.D., which was published in 1960 and sold over 30 million copies. The biracial British writer and the late Jewish American physician share the same philosophy: Envision the goal, believe you can accomplish the goal, and then achieve the goal.

When Bernardine Evaristo wrote her first novel, Lara, in 1997, she wrote, in part, an affirmation about winning the Booker Prize. Twenty-two years and eight books later, she finally received it. Dreams really do come true.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Interview with Arnold Lehman

by Kitty Kelley

In 1999, the Brooklyn Museum exploded a bombshell on the battlefield of artistic freedom and First Amendment rights with its exhibition “Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection,” which the museum’s director, Arnold Lehman, brought to Brooklyn from the Royal Academy in London.

In 1999, the Brooklyn Museum exploded a bombshell on the battlefield of artistic freedom and First Amendment rights with its exhibition “Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection,” which the museum’s director, Arnold Lehman, brought to Brooklyn from the Royal Academy in London.

Among the other provocative paintings in the exhibition, artist Chris Ofili’s “The Holy Virgin Mary” created an uproar at city hall. The painting depicted a Black Madonna with one breast created from shellacked and carefully decorated elephant dung. The painting outraged New York’s mayor, Rudy Giuliani, who tried to shut down the exhibit, fire the board and director, and throw the museum out of its historic building because he viewed the display as “sick” and “disgusting.”

The museum’s trustees, represented by attorney and First Amendment expert Floyd Abrams, sued Giuliani in  federal court to stop his attacks. The exhibition and lawsuit dominated New York’s front pages and the international media for six months. In the end, the museum was victorious. Now, Lehman retells this story — still relevant today — in a book appropriately titled in all caps, SENSATION: THE MADONNA, THE MAYOR, THE MEDIA, AND THE FIRST AMENDMENT.

federal court to stop his attacks. The exhibition and lawsuit dominated New York’s front pages and the international media for six months. In the end, the museum was victorious. Now, Lehman retells this story — still relevant today — in a book appropriately titled in all caps, SENSATION: THE MADONNA, THE MAYOR, THE MEDIA, AND THE FIRST AMENDMENT.

You’d been a museum director for 25 years when you brought “Sensation” to Brooklyn. The exhibition had already occasioned outrage in the U.K. Did you anticipate the same reaction in the U.S.?

I knew that “Sensation” included numerous strong, exciting, and provocative works, most not seen in the U.S., which was the reason I wanted it for the museum. However, at the Royal Academy in London, it was one painting, “MYRA,” that was the cause of the uproar. “MYRA” went almost unnoticed in New York. “The Holy Virgin Mary,” on the other hand, which the British media hardly mentioned, was the core of the frenzied media and legal battle in New York. However, I believe the outrage over the Madonna was planned and politically motivated.

What does the extreme reaction say about museumgoers in both countries?

“All politics” is often said to be local. Similarly, without the U.K. backstory of “MYRA” being a serial child-murderer, visitors to “Sensation” at Brooklyn only saw a huge portrait of a woman. For “The Holy Virgin Mary,” a backstory was created and incited by the conservative media to support Mayor Giuliani’s early race against Hillary Clinton for the New York Senate. The vast majority of New Yorkers approved of the Madonna despite the media frenzy, while the painting was never the center of any attention in London. In this instance, I believe the focus for the audiences was information rather than any cultural differences.

How much were the Brooklyn Museum’s legal fees, given that Mayor Giuliani opted to settle the case rather than wait for the opinion of the appeals court?

Even with a very substantial discount from our extraordinary attorneys, Floyd Abrams and Susan Buckley, preparing and prosecuting a First Amendment case in federal District Court [that was] continued in the court of appeals…together with the required depositions, court appearances, and a multitude of meetings, was a very time-consuming and costly undertaking. The museum raised funds from its dedicated trustees, engaged foundations, and other supporters to underwrite these costs.

Why did it take you two decades to write SENSATION and document the cultural clash?

Although many tried to “unseat” me, with the total support of our trustees, I remained director at the Brooklyn Museum for almost 16 more years. During that period, although I had always thought about writing a book on “Sensation,” I was both immensely busy and also believed strongly that it was inappropriate to write such a personal narrative about the institution I was then serving. With the beginning of the Trump Administration, I became increasingly concerned about the issues and challenges to the freedom of expression, which was critical to the very core of the battle over “Sensation.” It was at that moment I knew I had to write and publish SENSATION as soon as possible because of its relevance. The monumental undertaking of reviewing all the original research materials, much of which had been collected by my wife, took immense time. Hiring a researcher (which was made possible by a grant from the Ford Foundation), finding a publisher at the beginning of covid, and the actual writing, in total, took over three years.

Why is SENSATION being published in Britain and not the U.S.?

I approached several American publishers whose books I admired during my career. While there was enthusiasm expressed for the book’s concept, a mixture of current politics and the unknown stemming from the advent of covid were, I believed, deterrents to an agreement. Along with the others, I sent an outline and two unfinished chapters to London’s Merrell publishers, who had worked earlier with us at the Brooklyn Museum on several excellent publication projects. Hugh Merrell responded almost immediately that he had read everything I sent him, and despite being only art-book publishers, he offered to work with me on the book. My partnership with the incredible editor and designer assigned by Merrell to SENSATION was beyond superb. And the tangible book, amazing in every detail, is the result. SENSATION is a narrative or memoir, but it was produced as an elegant art book!

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Dishing With Kitty

by Judith Beerman

Originally published by The Georgetown Dish December 13, 2021

Internationally acclaimed writer and long-time Georgetown resident, Kitty Kelley is renowned for her bestselling biographies of the most influential and powerful personalities of the last 50 years.

Having captivated my friends with her insights into Frank Sinatra, Oprah and the Kennedys, the always charming and witty author graciously dishes with us!

1. Favorite spot in Georgetown?

The gardens and grounds of Dumbarton Oaks.

2. What place to visit next?

I dream about returning to Provence.

3. What’s last book you read that you recommend?

Not last book read but two of recent best: A Gentleman of Moscow by Amor Towles and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

4. What or who is greatest inspiration?

Those who reach outside themselves to help others like First Responders, Doctors Without Borders, MADD (Mothers Against Drunk Drivers), et. al.

5. Whom would you invite to next dinner party?

Dr. Fauci—to thank him.

6. What did you discover re: self during pandemic?

I look better masked!!

7. Spirit animal?

A cat, of course.

Interview with Ty Seidule

Kitty Kelley interviews the author of Robert E. Lee and Me, October 29, 2021