General

Shine

by Kitty Kelley

Tis the season, and January is the time for New Year’s resolutions. So, in that spirit, Larry Thompson, a Hollywood magnate, offers his book, SHINE: A Powerful 4-Step Plan for Becoming a Star in Anything You Do. Published in 2005, Thompson’s manual is an evergreen, he claims, and even more relevant for the new year of 2023. “If you’ll give me a few hours of your time,” he writes, “I will give you the knowledge to help you fulfill your dreams, and to rise and shine to meet your true destiny.” Snake oil sales pitch or road map to fulfilling dreams? You decide.

Tis the season, and January is the time for New Year’s resolutions. So, in that spirit, Larry Thompson, a Hollywood magnate, offers his book, SHINE: A Powerful 4-Step Plan for Becoming a Star in Anything You Do. Published in 2005, Thompson’s manual is an evergreen, he claims, and even more relevant for the new year of 2023. “If you’ll give me a few hours of your time,” he writes, “I will give you the knowledge to help you fulfill your dreams, and to rise and shine to meet your true destiny.” Snake oil sales pitch or road map to fulfilling dreams? You decide.

Thompson begins with his own story, growing up in Clarksdale, Mississippi, with a mother who urged him to leave home. “When you get educated,” Annie Thompson advised her son, “you’ve got to get out of this town ’cause [it’s] nothing but a graveyard with streetlights.” Like a stage mother (see the life stories of Gypsy Rose Lee, Shirley Temple, Elizabeth Taylor, Drew Barrymore, Brooke Shields, Dorothy Dandridge, Judy Garland, Groucho Marx), Larry Thompson’s mother pushed him. Pointing to the movie stars in Photoplay magazine, she said: “Now, they’re important. They have respect. I want you to go to Hollywood and be important like them.”

As further inspiration, Mama Thompson went to Memphis and bought a new dress, which she put in a box under her bed. “I’m saving that dress to wear when you invite me out to Hollywood to meet the Stars and to take me to the Academy Awards — on the night you win one.” Her dreams seeded his dreams. “I became driven,” he writes. “I developed the focus and the ambition and the high-level energy required to get there.”

Annie Thompson’s son left Mississippi at the age of 24 to live in California, where stars shine brightest. “Not only had I never been to California, but I had never met anyone who had ever been to California,” he recalls. Driving three days in a black Oldsmobile with maroon interior, Thompson arrived in Hollywood at 10 p.m. on a rainy night, exited the freeway onto Sunset Boulevard and reached the corner of Hollywood and Vine, where “I cried and cried and cried. I had arrived!”

Before beginning your ascent to stardom, Thompson recommends making a list of the great moments you’ve already had. He begins with his own, “The 150 Things I’ve done,” some of which are enviable, maddening and a couple gaspingly unbelievable:

No. 1: Sat on the deck of the Starship Enterprise with Captain Kirk.

No. 46: Made love in a royal balcony box at the La Scala Opera House in Milan.

No. 57: Witnessed the vision of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Medjugorje in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

No. 114: Helped President Gerald Ford become a mule. (Webster’s defines a mule as a cross between a donkey and a horse. The urban dictionary defines a mule as a carrier of things for someone else, usually illegal drugs. Thompson doesn’t explain.)

No. 140: Was ticketed on the way to Palm Springs doing 117 miles per hour in a Corniche.

No. 150: Became a multimillionaire along the way.

As you might expect of a Hollywood agent who’s managed the careers of “more than 200 stars,” there’s a heap of name-dropping: Elvis, Mama Cass, David Bowie, Peter Fonda, Tanya Tucker, Orson Welles, Drew Barrymore, Farrah Fawcett, Rene Russo, Mira Sorvino, Sylvester Stallone. You get the picture.

“Like wisdom and grace, Star quality is something you acquire,” Thompson writes. “A skill you can learn.” He defines and dissects the four elements of Stardom: Talent, Rage, Team, Luck, and provides a primer to each, complete with lists and exercises to do to become a Star. Using his own experience, he writes that Stardom is not an accident: “A drive will motivate you to move to L.A. or New York or Nashville. An Ambition will get you an agent. A passion will get you an acting job. A RAGE will make you a Star!”

Anyone who grows up feeling like an “outsider” or a “weirdo” has an edge. “There’s no one more likely to be a Star (Thompson always capitalizes Star) than someone who doesn’t fit in with the crowd.” Adversity helps. Growing up poor and impoverished in a broken family or learning to dodge bullets in New York’s Hell’s Kitchen ghetto, or being shuttled around foster homes with a begging bowl — each crippling experience bakes into the psyche the inspiration and resilience needed for Stardom.

Before beginning your ascent, the “Shine” meister advises: “Finding Your Team.” By this, he means deciding whether you’re a dog or a cat because you’re either one or the other. Cats, hard to get, are a bit mysterious with hidden agendas, and not totally forthcoming about anything and everything, and they let you get only so close. Dogs are uncomplicated. They adore you, they follow you. You tell them to sit, they sit. You tell them to heel, they heel.

Some in Thompson’s Star Kennel:

Star Dogs — Star Cats

George W. Bush — Bill Clinton

Jay Leno — David Letterman

Tom Hanks — Angelina Jolie

Billy Crystal — Warren Beatty

For some, Shine: A Powerful 4-Step Plan for Becoming a Star in Anything You Do might seem like a book of bromides — “Learn, Yearn, Burn, Discern.” “Dream Big” and “Don’t Give Up.” To others, it will become a bible that sits alongside Psycho-Cybernetics by Maxwell Maltz, M.D., who proved you can program your mind to achieve success and happiness, and Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way: A Spiritual Path to Higher Creativity.

Whether you’re a star dog or a star cat, the New Year of 2023 is yours to SHINE.

Originally published by The Georgetowner as an installment of “The Kitty Kelley Book Club”

Confessions

by Kitty Kelley

The writing life is full of potholes — long days and solitary nights followed by rewrites, rejections, and, for most, scant rewards. Upon publication of a work, critics descend from Mt. Olympus to dissect and dismember, which may explain why writers like A.N. Wilson wrap themselves in the protective carapace of grandiosity. In the first paragraph of his new memoir, Confessions, Wilson writes: “Fans and hostile critics alike have always spoken to, and of, me as one who was too fluent, who wrote with too much ease. Over fifty books published, and probably millions of words in the newspapers.”

The writing life is full of potholes — long days and solitary nights followed by rewrites, rejections, and, for most, scant rewards. Upon publication of a work, critics descend from Mt. Olympus to dissect and dismember, which may explain why writers like A.N. Wilson wrap themselves in the protective carapace of grandiosity. In the first paragraph of his new memoir, Confessions, Wilson writes: “Fans and hostile critics alike have always spoken to, and of, me as one who was too fluent, who wrote with too much ease. Over fifty books published, and probably millions of words in the newspapers.”

Quite a record for a British writer not born in Stratford-upon-Avon. And not to puff up an already overstuffed ego, but Andrew Norman Wilson can write — fluidly, gracefully, and with immense literary flourish. So, one might wonder about his memoir’s subtitle, A Life of Failed Promises. The disconnect, according to Wilson, is found in his self-assessment of a man who has squandered his potential.

At 72, he’s looking back on his life as a husband, a parent, a son, and a friend; sadly, he finds himself wanting. And who’s to argue as he admits to being “trapped” in his first marriage to a woman 13 years his senior, whom he blames for stealing “my youth, my experience of student life, my chance of developing an emotional spectrum with several girlfriends, before settling on the Right Moment to marry”?

Like a petulant child, Wilson retaliates with vitriol, leaving one to wonder if he was some kind of naïf who’d been shanghaied into marriage at 19 by a 32-year-old virago who bound and blindfolded him. They had two children together, and despite his many affairs (and a few of hers), remained married for 19 years, supposedly because of their religious vows.

Wilson maintains he was desolate in his first marriage and writes of how he tortured himself, becoming anorexic, not to mention enduring “two bouts of pneumonia, one of pleurisy and weight loss down to seven stone [98 pounds].” If not for hypnotherapy, he contends, “I think my eating disorder would probably have killed me.”

But then he fell in love with the woman who would become his second wife, until that marriage also ended in divorce. Before either of those wives came along, Wilson admits to having had “one fully fledged love affair” at his all-boys boarding school “that lasted nearly three years.”

Of his first marriage, Wilson writes: “I broke every vow and promise I ever made to that woman, including of course, the one about staying with her in sickness and in health.” He blames their split on “certain aspects of life with my difficult mother.” Years later, when his first wife tumbles into “alcohol numbed dementia,” Wilson visits her in “the care home,” adding less than chivalrously that her “uncertain control of bodily functions” made “taxi rides or visits to restaurants and cinemas anti-social.”

In keeping with the book’s title, Wilson confesses to the addiction of fame and seeing his name in print. “Cheap publicity,” he calls it, claiming it infected him as much as it did his “cherished friends,” the poet Stephen Spender and the philanthropist Lord Longford. He compares the “heady buzz” of seeing themselves in print to “the sadness of lonely mackintoshed men reaching greedily for magazines on the top shelf, in days before internet porn.”

Wilson further pleads guilty to being a full-throated snob who loves the monarchy, adores Diana, the late Princess of Wales, and reveres Margaret Thatcher as “the best Prime Minister of our lifetime.” He berates Oxford’s refusal to grant Thatcher an honorary degree as “shameful.” He claims not to be “a natural courtier,” yet devotes several pages to his dinners with Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, and the near national scandal he caused by reporting her table talk about T.S. Eliot and his “dreary” recitations of The Waste Land, which convulsed the royal family into fits of giggles.

Page after page charts Wilson’s back-and-forth religious forays from the Church of England to the Church of Rome. He once entered an Anglican seminary intent on becoming an Episcopal priest, but he left after a year. He then converted to Catholicism, but that, too, was temporary. He now rages against Catholicism’s “preposterous claim” of papal infallibility and the “authoritarian clericalism [that] has so obviously helped to cover up, perhaps even to encourage, the abuse of children by priests.”

Admitting that his life has been a tangle of spiritual confusion, he recounts how, in 1989, he descended from the heights of piety to meander in the nether region of agnosticism. “I think that all churches have faults but all also have members whose lives shine with the life of Christ, and that this has been true in the C of E as it has in the other churches.” He then adds, “I still read the New Testament in Greek each year.”

The surprise of this book comes from its lackluster ending, which is not a bang but a whimper. After confessing his thundering ambitions, he writes remorsefully of the “young A.N. Wilson, so full of himself, so unfaithful, not only to his wife [make that two wives] but to his own better nature.” Unable to find peace in religion or happiness in marriage late in life, he seeks redemption in his talent. After all, he concludes, “[E]ven the feeblest of writers [know] why writing and reading play such a vital part in our lives.”

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Shirley Hazzard

by Kitty Kelley

Shirley Hazzard’s first short-story submission was plucked from a slush pile of 30,000 unsolicited manuscripts at the New Yorker by fiction editor William Maxwell. And then, just like an unknown Lana Turner being discovered while sipping a soda at Schwab’s drugstore, a star was born. The Hollywood star married eight times, and the writer only once, but Hazzard wrote about love the way Turner pursued it — as something perishable that, in the reshaping of our minds, becomes permanent: “the only state” in which “all one’s capacities are engaged.”

Shirley Hazzard’s first short-story submission was plucked from a slush pile of 30,000 unsolicited manuscripts at the New Yorker by fiction editor William Maxwell. And then, just like an unknown Lana Turner being discovered while sipping a soda at Schwab’s drugstore, a star was born. The Hollywood star married eight times, and the writer only once, but Hazzard wrote about love the way Turner pursued it — as something perishable that, in the reshaping of our minds, becomes permanent: “the only state” in which “all one’s capacities are engaged.”

(So ends the stretched connection between the MGM star from Idaho and the Australian writer who moved to New York in her 20s and eventually traveled in the city’s intellectual circles with Lionel Trilling, Muriel Spark, Alfred Kazin, and Dwight MacDonald.)

Shirley Hazzard (1931-2016) died at 85, sadly of dementia, but left behind six books of nonfiction, four novels (The Transit of Venus being her masterpiece), and two story collections. In two of her nonfiction books, she blasted the United Nations, where she had worked in the “dungeons” for several years. She emerged from that experience disillusioned and dyspeptic, and lambasted its supporters, including Margaret Mead and U.N. Under-Secretary-General Brian Urquhart. He, in turn, dismissed Hazzard as a no-nothing, unpaid secretary.

In 1980, she wrote an article for the New Republic exposing the Nazi past of Kurt Waldheim, which had allowed him to rise to become U.N. secretary-general from 1972-1981 and president of Austria from 1986-1992. Hazzard’s exposé failed to galvanize public attention, but things changed five years later when writer Jane Kramer expanded on Hazzard’s Waldheim revelations.

At first, Hazzard was offended at having been overlooked in bringing the story to light but was “slightly mollified” when Kramer wrote to her: “You deserve enormous credit for being…as I now know the only person to have persisted in publishing the truth about that odious man over all these years when it was convenient to pretend he was decent.”

Hazzard’s fiction garnered impressive prizes, including the O. Henry Award, National Book Award, William Dean Howells Medal, Miles Franklin Award, and National Book Critics Circle Award. Yet for all her literary achievements, she was not as celebrated as some think she deserves to be, and that includes her biographer, Brigitta Olubas.

A literary scholar at the University of South Wales, Olubas has been researching her subject for three decades. Among other works, Olubas wrote “Cosmopolitanism in the Work of Shirley Hazzard” (2010); “Shirley Hazzard’s Capri” (2014); “The Short Fiction of Shirley Hazzard” (2018); and “Shirley Hazzard’s Post-War World” (2020). Now comes Shirley Hazzard: A Writing Life, Olubas’ full-throated chronicle of the writer advertised as “the first biography of…a writer of ‘shocking wisdom’ and ‘intellectual thrill.’” Those last two quotes come from a 2020 New Yorker profile of Hazzard and are heartily underscored in this work.

Olubas seems determined to prove that Hazzard is to Australia what Joan Didion is to America: a literary icon. Growing up in Sydney with a bipolar mother and an alcoholic father, Hazzard was devastated when her family had to move to New Zealand because her sister, her only sibling, was ill with tuberculosis. As a youngster, Hazzard was surrounded by wounded WWI veterans, and she saw the devastation of Hiroshima at 16, which infused her novels with inevitable loss.

Her later years with husband Francis Steegmuller, a quarter-century her senior, were her happiest and most creative. Steegmuller, a Flaubert scholar, and Hazzard divided their lives between Capri and Manhattan, becoming significant figures in their rarified circle of academics, poets, and writers. During this time, they befriended Graham Greene, a relationship Hazzard later memorialized in Greene on Capri. Yet Greene’s widow later dismissed Hazzard as a know-it-all harpy and claimed her husband felt Hazzard “intruded herself too much” and “had a tendency to talk a great deal.”

Olubas describes Hazzard, with her limited formal education, as “an exquisite stylist, skilled linguist, and fiercely intellectual autodidact.” She acknowledges Hazzard’s dominant (at times domineering) personality and insistence on commandeering conversations and reciting endless reams of poetry. Hazzard spoke in long paragraphs, as if being filmed; she disliked television and read Herodotus over lunch. She commanded attention in her starched shirts, Chanel tweeds, and a beret that covered her teased bouffant. She bemoaned growing old, especially during her last years as a widow, ailing and alone.

Given complete access to Hazzard’s diaries and journals, Olubas was able to climb into her subject’s mind and heart and find the answers to how Hazzard felt at various times and why she said what she said and did what she did — the kinds of questions that perplex many biographers, forcing them to guess and surmise. Brigitta Olubas has made glorious use of her years as a Shirley Hazzard scholar, too, and in this biography, she eloquently presents all that was won and lost in Hazzard’s writing life.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Listen, World!

by Kitty Kelley

Remember that iconic scene in “The Mary Tyler Moore Show”? Mary’s editor, Lou Grant, played by Ed Asner, says, “You know, Mary. You’ve got spunk.”

Remember that iconic scene in “The Mary Tyler Moore Show”? Mary’s editor, Lou Grant, played by Ed Asner, says, “You know, Mary. You’ve got spunk.”

She beams. “Why, thank you, Mr. Grant.”

He growls. “I hate spunk.”

Lou Grant would’ve been brought to his knees by Elsinore Justinia Robinson, who was spring-loaded with spunk — hell-bent, fire-popping spunk. As the highest paid female columnist for Hearst newspapers, she was syndicated to 20 million readers and wrote like a rocket, filing over 9,000 stories in 40 years. A passionate autodidact, she also wrote poetry, short fiction, and essays, and published many children’s books that she illustrated herself. In 1934, she wrote her memoir, I Wanted Out.

Yet for being one of the most famous people in America, Elsie Robinson was virtually forgotten after her death in 1956. Now, decades later, we have the first biography of this female phenom, described by her biographers as an “all-around badass!” Julia Scheeres and Allison Gilbert spent more than 11 years researching and reporting to write Listen, World! How the Intrepid Elsie Robinson Became America’s Most-Read Woman, the life story of this life force.

Born in 1883, Elsie grew up in Benicia, California, a small town which “permitted uncorked hedonism,” and where F Street divided the community. Downtown was “saloons…and sporting women.” Uptown was churches and knee-bending nuns. Elsie lived uptown — the “good” side of town — near the high stone walls of St. Catherine’s Convent, but she prized downtown.

“Goodness, though it promised halos in heaven, certainly didn’t offer a lively gal many breaks on earth,” she wrote in her memoir. “Bad Women, on the contrary, had practically unlimited freedom and fun.”

Elsie was a “lively gal” times 10, a free spirit from the West as unsinkable as Molly Brown, and as uncorseted by social strictures as Annie Oakley. When Christie Crowell, a widower from the East who’d traveled to California after the death of his young wife, first met Elsie, he was captivated by her enthusiasm. Soon, he proposed, and she accepted.

He happily wrote to his parents with the news, but they responded with grave reservations. They felt their already-shaky social status in Brattleboro, Vermont, would not be enhanced by a young woman from a working-class family in the town that spawned the California Gold Rush, hardly a citadel of moral rectitude. So, they did all they could to dissuade their son from pursuing the marriage.

“After months of epistolary discourse, the Crowells set down their terms,” write Scheeres and Gilbert. “Christie could marry Elsie on one condition: she must attend a seminary school to learn household management, elocution and the Bible…to become a fitting bride for their son.”

You might think that, at this point, the high-spirited Elsie would tell Christie and his parents to stuff their seminary school, but in the early 1900s, a young woman’s options were severely limited — either marry or mildew — so Elsie agreed to their terms. As she would later learn, however, even a married woman’s status was no higher than the family dog’s. She stayed with her husband for nine years, until Christie demanded a divorce on the only grounds available — adultery. Reflected Elsie:

“So solemn was marriage, so shameful divorce that the thought of separation had never as yet crossed my mind. Someday it will seem incredible that any woman should have faced such shame, such deliberate torture as I was about to face.”

On almost every page of this engaging biography, the authors weave in bits of Elsie’s writings, putting her opinions and insights into italics so the reader knows exactly what was on her mind. They don’t have to speculate about how Elsie felt living in the same house with her snooty in-laws; they have her diaries, interviews, letters, and newspaper columns to tell them. Yet even with such a cornucopia of information, the authors still insert “might have felt,” “surely thought,” and “was likely oblivious” here and there, sprinkling “perhaps” and “presumably” throughout their presentation of this fascinating woman who survived every obstacle she ever met.

The highlight of Elsie’s life was the birth of her only child, George, who suffered from severe asthma attacks, forcing him to miss weeks of school. In 1926, the young man found a small lump in his foot that was surgically removed. But after being released from the hospital, he was wracked by fever, chills, and severe chest pain. Elsie wrote a column filled with her anguish:

“I’m afraid…Fear runs through all my life. I cannot mark its course with a definite line, but its grim shadow tinges my brightest moments and noblest dreams…I have only found one way to manage fear…Go on! No matter how terrible your inward agony, go on! Don’t wait until the darkness lifts. Grab each small task, whether it appeals or not! Keep doing something! Go through the gestures of normal life! Eat, talk and smile as though all things were well. Then gradually your inner body will conform to your firm fighting front. Your thoughts will cease their maddened hammering at your skull. You will not banish fear, but you’ll have conquered it and made it run to heel.”

Hear, hear, Elsie!

George Alexander Crowell took his last rasping breath at age 21 with his mother by his side. Elsie tried to outpace her unmanageable grief with round-the-clock work. “There are no details when the thing you have loved best goes on. Only a wailing, witless darkness…the sense of utter bankruptcy.” In 1928, the 48-year-old Elsie finally buckled to the unmitigated pain and suffered a nervous breakdown.

Throughout her life, Elsie Robinson used her national platform to express her increasingly progressive views. She supported labor unions; she ridiculed Prohibition; she denounced the death penalty. During the 1930s, she railed against the Nazis and rallied Americans to support Jewish refugees. She condemned racism and excoriated the Daughters of the American Revolution for refusing to let Paul Robeson perform in their concert hall.

“And on what, may I ask, do you base your supremacy?” she wrote in her syndicated column. “You didn’t choose your ancestors…You happened to be born white…you could have put aside ignorance and prejudice and contemptible snootiness…and given your lives for unity. But you weren’t big enough. You weren’t brave enough.”

God bless you, Elsie!

Listen, World! is a glorious biography for all the women who deserve to see themselves on life’s pedestal — and for all the heroic men who help lift them up.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

David Bruce Smith’s Grateful American Book Award Honors Michelle Coles

by Kitty Kelley

No one hosts a more spectacular dinner party for a better cause than David Bruce Smith. His heavy parchment invitations of exquisite calligraphy arrive each fall to announce his Grateful American Foundation’s Book Award for the best children’s book of the year. The 2022 recipient was Michelle Coles for her first novel, Black Was the Ink. Coles joined previous winners, such as Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayer for her 2021 children’s book, The Beloved World of Sonia Sotomayer, and Child of the Dream: A Memoir of 1963 by Sharon Robinson, daughter of Jackie Robinson, the first African American to play in Major League Baseball.

The Grateful American Book Award comes with a check for $13,000, “a patriotic nod to the 13 original colonies,” says Smith — plus a lifetime pass to the New York Historical Society because, he says, “It’s hallowed objective is to celebrate knowledge,” and a medal, “designed by my mother, Clarice,” a noted artist who died a few months ago. Smith’s late father, Robert H. Smith, donated hundreds of millions to educational and cultural organizations throughout the Washington area, and his son and heir now continues his family’s philanthropy. David said his father, an immigrant’s son, “described himself as a ‘grateful American,’ which seemed a perfect name for my dream.”

“I started the Grateful American Foundation in 2014 because I heard an NPR report which indicated that Americans had a low level of historic literacy,” Smith said. “My friend, Bruce Cole, then Chairman of the National Endowment of the Humanities, suggested I create a book prize. So, with help and advice, I did just that. I selected 7th to 9th graders as my target because that age is probably one of the most difficult times for adolescents…. It’s my feeling that if a kid doesn’t want therapy, a book can — at least — be a paper psychiatrist.”

Smith, who’s dedicated to building youthful enthusiasm for American history, and co-authors a lively blog entitled “History Matters,” has written and published 13 books, many about his family, including his grandfather, Charles E. Smith, whose legacy remains the life communities he built during the 1960s in Washington and Maryland.

For this year’s celebration, Smith chose the Perry Belmont House, a magnificent Beaux Arts mansion, near Dupont Circle on New Hampshire Avenue NW, built in 1909. Guests were agog as they arrived. “Sublime, isn’t it,” said John Danielson, walking up the baroque marble steps and gesturing to the sculptured décor and channeled stonework. “A stunning home from a bygone era to celebrate David’s triumph in creating the Grateful American Book Prize.”

A man of immense charm, Danielson is chairman of the Education Advisory Council for the financial services firm of Alvarez and Marsal. He lives in Georgetown and seems to know everyone in the city, as he graciously introduces Douglas Bradburn, CEO of Mount Vernon and his wife, Nadene; Matthew Hiktzik, producer of the 2004 Holocaust documentary film, Paper Clips; Mindy Berry, Senior Executive at the National Endowment for the Humanities; Teddi Marshall, C-suite business executive; Doreen Cole, whose late husband was the longest serving chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities; writer Michael Bishop; Neme Alperstein, teacher with the NYC Dept. of Education; Courtney Chapin, Executive Director of Ken Burns’s Better Angels Society; Scott Stephenson, director of the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia, Elizabeth Robelen, long-time editor for the Washington Independent Review of Books and her husband, Carter Reardon, instructor with the Dog Tag Fellowship Program for veterans at Georgetown University.

“Helping those who bring history to young people is an important purpose of this evening,” said David O. Stewart, who’s written several prize-winning books, including George Washington: The Political Rise of America’s Founding Father.

Knight A. Kiplinger opened the award presentation by introducing himself as a history nerd. “I come from a long line of history nerds,” said the publishing mogul. “My late father, Austin Kiplinger, and I (both of us journalists, too) have been passionate supporters of local history.” The results of that family passion — the Kiplinger Collection and the Kiplinger Research Library — now reside in the renovated Carnegie Library on Mt. Vernon Square, which has morphed into the D.C. History Center.

All history nerds and grateful Americans gave the evening rounds of rousing applause.

Originally published in The Georgetowner, November 9, 2022

Saving Freud

by Kitty Kelley

Lights! Camera! Action!

Lights! Camera! Action!

Andrew Nagorski’s Saving Freud ought to be coming to a theater near you. This nonfiction work crackles like a novel and sparks with the razzle-dazzle of a big-screen extravaganza: an unforgettable cast of characters (think The Dirty Dozen), spine-tingling suspense (The Day of the Jackal), a death-defying savior (maybe Mephisto), and Nazis — the epitome of evil.

“This book is definitely not The Sound of Music, but it’s part biography and part thriller,” Nagorski told an audience recently gathered at Politics and Prose in Washington, DC, to discuss the publication of his eighth book. Having written Hitlerland: American Eyewitnesses to the Nazi Rise to Power, The Nazi Hunters, and 1941: The Year Germany Lost the War, the former Newsweek bureau chief has mastered the Nazi terrain.

The plot of Saving Freud centers on how a group of six loving friends of the world-famous psychoanalyst finally convinced him to leave Austria in 1938 on the jack-boot heels of Hitler’s storm troopers as they invaded Vienna.

Even as the Nazis banged down the doors of his office and home at Berggasse 19, Sigmund Freud, then 81, still believed he’d be spared the catastrophe that had befallen other Viennese Jews. Without saying a word, he glared at the intruders looting his apartment. Hitler’s minions seemed visibly intimidated. They addressed him as “Herr Professor” and backed out of the apartment, loot in hand, stating they would return at another time.

When the Nazis then burned his confiscated books in the public square, Freud seemed unperturbed. “What progress we are making,” he told a patient. “In the Middle Ages they would have burned me. Now they are content with burning my books.”

Freud could’ve escaped years before, but he refused to join the hordes of Jews fleeing Vienna in the early 1930s. Referring to himself as a “Godless Jew” and an atheist, he maintained he was immune from persecution because he was not religious. His sole allegiance to Judaism, he said, was to not deny being born a Jew. He also considered himself apolitical and therefore safe from the upheaval thrashing around him.

Interestingly, while revolutionary in his thinking, Freud led a conventional life centered around hearth and home. “I’m all for sexual freedom,” he once remarked, “but not for myself.”

Nagorski admits that when it came to the Nazis, Herr Doktor Freud, a world-shaking intellect known for his revolutionary theories, was “naive…astonishingly naïve.” Others might say dumbfoundingly reckless given that he was determined to live out his days in Vienna even after the Anschluss in March 1938, when Germany annexed Austria.

At that point, Freud’s adoring circle whirled into action, determined to seek asylum for him and his family in London so he could realize his life’s wish “to die in freedom.” The group included Maria Bonaparte, princess of Greece and Denmark, who lived in Paris as a practicing psychoanalyst after seeking Freud’s help to achieve orgasm. She provided Freud with the protection money he needed to bribe his way to safety.

Another member was William Bullitt, U.S. ambassador to Russia and France, who’d sought Freud’s counsel when his marriage was falling apart. During their sessions, they discovered they both despised Woodrow Wilson and later collaborated on a biography of the former president that was published in 1966 to “overwhelmingly negative” reviews.

Also part of the group was Dorothy Tiffany Burlingham, granddaughter of the renowned jeweler who founded Tiffany & Co., who became the lifelong partner of Freud’s beloved daughter Anna. Next was Ernest Jones, a onetime patient and close friend of Freud’s, and president of the International Psychoanalytical Association. Jones flew to Vienna in 1938 to insist that Freud leave the country. “This is my home,” the psychoanalyst said. “Your home is the Titanic,” retorted Jones.

Max Schur, who became Freud’s physician and treated him for the throat cancer he suffered as a result of refusing to give up cigars, played a role, too. When Schur’s family emigrated to the U.S. to escape the Nazis, the doctor remained in Vienna until Freud’s departure for England. Only then, after arranging for Freud’s medical care in London, did Schur join his own family in America.

Dr. Anton Sauerwald, a Nazi bureaucrat, is the shocking thunderbolt in this rescue saga and the team’s unlikeliest member. He was assigned by Nazi high command to rifle through Freud’s financial documents and destroy his historic library, but as an admirer of the pioneer of psychoanalysis, he did neither. Instead, Sauerwald removed evidence of Freud’s foreign bank accounts and arranged for his massive collection of books, papers, and journals to be secretly stored in the Austrian National Library, where they remained hidden until after the war.

Each figure was crucial to the rescue because it took all six working in concert to get Freud to leave his home and office for England, where he spent the remaining 15 months of his life at 20 Maresfield Gardens, Hampstead, in North London. There, his rescuers had recreated his consulting room in faithful detail.

The British press heralded his arrival with effusive coverage, and Freud’s new life of freedom gave him great pleasure. As he wrote to his brother in Switzerland: “Our reception was cordial beyond word. We were wafted up on wings of mass psychosis.” He was welcomed into the Royal Society of Medicine and visited by prominent guests like H.G. Wells and Salvador Dali.

Still, Freud missed Vienna. “The feeling of triumph on being liberated is too strongly mixed with sorrow,” he confided to a friend, “for in spite of everything I still greatly loved the prison from which I have been released.”

Freud’s life of freedom ended for good on September 23, 1939, when his pain became excruciating and, as he told his physician, “the torture makes no sense anymore.” Remembering his promise, Dr. Schur gave his patient an injection of morphine which led to Freud’s “peaceful sleep.” As his adored Anna later told a friend:

“I believe there is nothing worse than to see the people nearest to one lose the very qualities for which one loves them. I was spared that with my father, who was himself to the last minute.”

Saving Freud seems to have been written for the silver screen, and one can only hope that someone like Steven Spielberg finds his way to this book.

(Collage of press clippings from Freud Museum.)

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

My Place in the Sun

by Kitty Kelley

Sometimes, the sons of famous fathers are cursed. “They’re born on third base and think they’ve hit a triple,“ according to the adage. Seldom do they hit a home run. Not so the namesake of director, producer, screenwriter, and cinematographer George Stevens (1904-1975), who elevated films from entertainment to enlightenment with A Place in the Sun, Shane, Giant, The Diary of Anne Frank, and The Greatest Story Ever Told.

Sometimes, the sons of famous fathers are cursed. “They’re born on third base and think they’ve hit a triple,“ according to the adage. Seldom do they hit a home run. Not so the namesake of director, producer, screenwriter, and cinematographer George Stevens (1904-1975), who elevated films from entertainment to enlightenment with A Place in the Sun, Shane, Giant, The Diary of Anne Frank, and The Greatest Story Ever Told.

His son — “Young George,” “Georgie,” or “George, Jr.” — was born on third base, but now he’s nearly 90 years old and is proudly waving his scorecard in My Place in the Sun: Life in the Golden Age of Hollywood and Washington.

George Stevens Jr. is Tinsel Town royalty. He springs from five generations of stage actors, silent screen stars, and drama critics, including his father. Stevens père, a two-time Academy Award winner, was a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Signal Corps during WWII and  headed a film unit that documented the D-Day landings at Normandy, the liberation of Paris, and the Allied discoveries of the Duben labor camp and the concentration camp at Dachau.

headed a film unit that documented the D-Day landings at Normandy, the liberation of Paris, and the Allied discoveries of the Duben labor camp and the concentration camp at Dachau.

Stevens fils found these treasures and more in his late father’s storage bin and put them to good use in this work, a phenomenal history of Hollywood that’s as much a paean to a beloved father as it is an accomplished record of the adoring son, who propelled the family legacy forward into television (at 27, George Jr. was directing Alfred Hitchcock Presents for CBS) and prize-winning documentaries. In addition, he founded the American Film Institute (AFI) in 1966 and, for 38 years, produced The Kennedy Center Honors.

There are more names dropped in this memoir than in the Book of Jehovah. “Bobby and Ethel”; “My good friend, Tom Brokaw”; “Teddy”; “My rabbi, Vernon Jordan”; and “My buddy Art Buchwald.” One wonders if Stevens has ever known a no-name plumber or lowly key grip. Here’s just a sample of his life on the celebrity circuit:

“My calendar shows days filled with organizing a new [film] school and stimulating evenings during which I spread word about AFI to the Hollywood community; ‘Dinner at the [Gregory] Pecks — Mr. and Mrs. Jean Renoir, Omar Sharif and Barbra Streisand; dinner at home — John Huston and Shirley MacLaine; dinner at Danny Kaye’s with Pecks and Isaac Stern; dinner at George Englund’s w/Warren Beatty, Paul Newman, Robert Towne.’”

Despite the marquee names (and there are pages of them), there is no braggadocio. In fact, there’s a bit of the fanboy in this man who once asked President Clinton to sign their scorecard after playing golf together. George Stevens Jr. displays the self-deprecating style of someone enthralled by his work, engaged by his politics, and enriched by his friends. His memoir, gracefully written, shows a man who knows that blessings accrue to those who take the high road.

Accustomed to flying smooth skies, Stevens was not prepared for the turbulence he encountered when David M. Rubenstein, chair of the Kennedy Center, forced him out as producer of The Kennedy Center Honors. Stevens writes that Rubenstein came to his office on a Good Friday in what “proved to be a disturbing and somewhat bizarre meeting…[Rubenstein] seemed to apologize, saying this was his most difficult meeting since the time he fired George H.W. Bush and James A. Baker from his Carlyle enterprise.” He continues:

“Again, insufficient paranoia had let me down. David’s riches, after all, had come from hostile takeovers of corporations — ousting existing management, cutting costs and reaping windfalls. On reflection, my response was less tempered than I would have liked. ‘I think you’ll have to look around for a long time to find producers who will give you five consecutive Emmys.’”

Since parting ways with the Stevens Company in 2014, The Kennedy Center Honors has won a few Emmys but not yet “five consecutive” ones. For his part, Stevens writes, “It’s too bad it ended the way it did, but the passage of time now allows me to look back on the somewhat indecorous circumstances of my departure with what Wordsworth called ‘emotion recollected in tranquility.’”

Just when the reader is floating on the sweet vapors of a golden life among the good and the great, Stevens brings you to your knees with the worst that can befall a parent. In 2015, he and his wife, Elizabeth, lost their 49-year-old son, Michael, to stomach cancer. This chapter, entitled “Courage,” is a chapter no parent ever wants to write. Stevens keeps it short:

Just when the reader is floating on the sweet vapors of a golden life among the good and the great, Stevens brings you to your knees with the worst that can befall a parent. In 2015, he and his wife, Elizabeth, lost their 49-year-old son, Michael, to stomach cancer. This chapter, entitled “Courage,” is a chapter no parent ever wants to write. Stevens keeps it short:

“Not a day goes by that I do not think of Michael Stevens.”

He ends his book as he began it — by extolling the work that has defined his life for decades. He quotes Bertrand Russell, who wrote about the same subject at the same age in “The Pros and Cons of Reaching Ninety”: “A long habit of work with some purpose that one believes is important is a hard habit to break.”

Last seen, Stevens was heading for his office “to ponder stories that might become films, though an awareness that each new film is a commitment of years makes me a little less keen to toss my cap over the wall. However, now that the storytelling juices that have been devoted to this book are freed up, who knows what lies ahead.”

We can only hope.collection

(Photos: George Stevens Sr. with George Stevens Jr., Michael Stevens from Stevens Family Collection, Margaret Herrick Library and the Academy Film Archive https://www.oscars.org/collection-highlights/stevens-family-collection/?)

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Undelivered

by Kitty Kelley

“For all sad words of tongue and pen,

The saddest are these, ‘It might have been.’”

These woeful words from Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier might apply to politicians and lovers and horses who’ve never made the winner’s circle. Those losses are particularly painful for politicians who are expected to concede gracefully and congratulate the fiend who just walloped them. As Rep. Morris Udall said after losing the 1976 Democratic nomination for president, “It’d be less painful to get mowed down by an 18-wheeler.”

These woeful words from Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier might apply to politicians and lovers and horses who’ve never made the winner’s circle. Those losses are particularly painful for politicians who are expected to concede gracefully and congratulate the fiend who just walloped them. As Rep. Morris Udall said after losing the 1976 Democratic nomination for president, “It’d be less painful to get mowed down by an 18-wheeler.”

Hillary Clinton felt the same way in 2016 after winning the popular vote for president by over 4 million votes but losing the Electoral College by 306-232, and thus the presidency. The former secretary of state/U.S. senator/first lady was poised to claim victory with prepared remarks thanking “my fellow Americans” for “reaching for unity, decency and what President Lincoln called ‘the better angels of our nature.’”

But those better angels flew away as Clinton acknowledged her loss to Donald J. Trump with civility and just a  couple of tears. After thanking her family, staff, volunteers, and contributors, she apologized to them, becoming the first presidential candidate in history to say “I’m sorry” in a concession speech.

couple of tears. After thanking her family, staff, volunteers, and contributors, she apologized to them, becoming the first presidential candidate in history to say “I’m sorry” in a concession speech.

Now we’re finding out what Clinton would’ve said as president-elect had she won the campaign that cost over $581 million. Her six-page victory speech, never given, is reported in full by Jeff Nussbaum in his creative new book, Undelivered: The Never-Heard Speeches that Would Have Rewritten History.

Some of the unspoken speeches unearthed by Nussbaum’s dogged research and informative text spark jump-up-and-down joy, particularly those in the section entitled “The Fog of War, The Path to Peace.” Each of its three segments is noteworthy, beginning with the words of apology General Dwight D. Eisenhower would’ve delivered if the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944, had failed.

“The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do,” he wrote in a brief, four-sentence statement. “If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone.” Nussbaum, a speechwriter for Democrats, recognizes Eisenhower’s words as “an object lesson in the language of leadership and responsibility.”

Knowing that “victory has a hundred fathers and defeat is an orphan,” President John F. Kennedy prepared a never-delivered speech to the nation in 1962 to announce airstrikes on Cuba “to remove a major nuclear weapons build up.” The president had gathered his top cabinet officers — hawks and doves alike — to debate the issue and discuss what to do.

“Each one of us was being asked to make a recommendation which would affect the future of all mankind,” wrote Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy of the Cuban Missile Crisis, “a recommendation which, if wrong and if accepted, could mean the destruction of the human race.” For 13 days, the U.S. teetered on the edge of war with the Soviet Union, until Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev blinked and removed his missiles.

The third example of an undelivered speech that might’ve changed history is Emperor Hirohito’s apology for Japan’s role in World War II, which he wrote in 1948, lamenting the “countless corpses…[left]…on the battlefield [and] the countless people [who] lost their lives…Our heart is seared with grief. We are deeply ashamed…for our lack of virtue.”

Now to the bits that don’t stir jump-up-and-down joy. Much of Nussbaum’s book reads like a garrulous guy on a binge while his editor is A.W.O.L. The author meanders back and forth from a third-person narrative to first-person asides, political anecdotes, pesky footnotes, and lame jokes (see the one about St. Peter and speechwriters). He jams his book to the brim with historical information, proving that he’s read widely, and is hellbent on sharing every bit of his findings, which he piles into 374 pages of main text, 38 pages of notes, a 30-page bibliography, and a 28-page appendix. (Dear Santa: Please put a copy of Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style in Nussbaum’s Christmas stocking.)

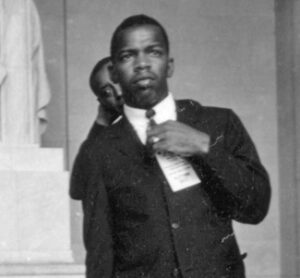

An example of what might be described as logorrhea begins in the first chapter and deals with late congressman John Lewis’ proposed speech at the 1963 March on Washington. Lewis’ original remarks were deemed too fiery for Archbishop Patrick O’Boyle, who refused to make the morning’s invocation if Lewis didn’t tone down his rhetoric. March organizers pressured Lewis, saying that without the Irish Catholic prelate, they might lose support from the Irish Catholic president, which would influence Congress and doom Civil Rights legislation. So, Lewis compromised.

An example of what might be described as logorrhea begins in the first chapter and deals with late congressman John Lewis’ proposed speech at the 1963 March on Washington. Lewis’ original remarks were deemed too fiery for Archbishop Patrick O’Boyle, who refused to make the morning’s invocation if Lewis didn’t tone down his rhetoric. March organizers pressured Lewis, saying that without the Irish Catholic prelate, they might lose support from the Irish Catholic president, which would influence Congress and doom Civil Rights legislation. So, Lewis compromised.

At this point, the author-in-need-of-an-editor interrupts his story of Lewis’ speech to relate his own stories of being a speechwriter at the Democratic National Convention from 2000 through 2020. He rambles on about Melania Trump, who lifted from Michelle Obama’s speech, Al Sharpton’s refusal to use a teleprompter, and Barney Frank’s speech impediment, and includes brief mentions of 2012 Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney, his wife, Anne, and the GOP convention’s keynote speaker, New Jersey governor Chris Christie. (P.S. to Santa: Please add Arthur Plotnik’s Spunk & Bite: A Writer’s Guide to Bold, Contemporary Style to that stocking.)

Eventually, Nussbaum circles back to the dilemma facing Lewis, but only for a few pages before he interrupts the narrative again with more reflections on his own speechwriting. Then, and only then (thank you, Jesus), does he return to finish the story of Lewis and his 1963 speech.

Note to readers: Lewis’ undelivered speech is just the book’s first chapter. You’ve got 14 more to go. (P.P.S. to Santa: Forget your sleigh. Use FedEx.)

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

(Photos: John Lewis at the Lincoln Memorial, 1963 © Estate of Stanley Tretick; Hillary Clinton conceding, 2016, PBS/YouTube)

The Summer Friend

by Kitty Kelley

The spectacular cover of Charles McGrath’s The Summer Friend deserves its own trophy. It shows a photograph of an apricot sun setting on gentle waves that lap a sandy beach. Sea grasses sway in a breeze that has blown away footprints, never meant to last too long. The sand-dune fencing beyond the shore also bends to the wind, a force of nature that will not be denied. The elegiac scene could just as easily be an early morning sunrise, but since it wraps around a book of memories, a setting sun seems more appropriate.

The spectacular cover of Charles McGrath’s The Summer Friend deserves its own trophy. It shows a photograph of an apricot sun setting on gentle waves that lap a sandy beach. Sea grasses sway in a breeze that has blown away footprints, never meant to last too long. The sand-dune fencing beyond the shore also bends to the wind, a force of nature that will not be denied. The elegiac scene could just as easily be an early morning sunrise, but since it wraps around a book of memories, a setting sun seems more appropriate.

The Summer Friend celebrates a seasonal bond between two men, both nicknamed “Chip,” who favor khaki pants and meet every summer to share their passion for fishing and sailing and golf. Still, the title puzzles. Why “the” instead of “my” friend? Is it because “the” imposes a certain emotional distance, as if the author is referring to a casual acquaintance, whereas “my” speaks to a closer relationship promising something more intimate?

In this case, “the” seems to represent the surface level of many male friendships compared to the deeper bonds that women establish. The Summer Friend peeks inside the psyche of one such male friendship between not-quite bros forever but seasonal pals. As such, this memoir is pitch-perfect for outdoorsy dads, sons, brothers, uncles, nephews, and the like.

McGrath, a scholarship student at Yale (class of ’68), made his way as a man of letters, having been deputy editor of the New Yorker and a former editor of the New York Times Book Review. Currently, he’s editor of Golf Stories and an occasional contributor to Golf Digest.

Despite his literary credentials, there’s a bit of whoopee cushion in the writer, who recalls with glee the cigarette load, a practical-joke device he and his brother inserted into the tip of one of their mother’s Old Gold cigarettes. When she lit up, it exploded.

“Childish, I know,” writes McGrath, now 76, “but the memory of my mother standing there, wide-eyed, with an exploded cigarette in her mouth still makes me tear up with laughter.”

Not surprisingly, the prankster grew up to love fireworks; even today, as a grandfather, he spends hundreds of dollars on July Fourth celebrations, where he shoots off poppers, rockets, salutes, and crackers by the brick and half-brick. In fact, he devotes an entire chapter to “Blowing Stuff Up.”

The chapter that most defines McGrath, however, is “The Camp,” and his memories of the month-long vacations his family took to the type of log-built lodge familiar to many households across the country back then. For the McGraths, it was “a temporary sun-dappled idyll, a glimpse of another kind of life,” where kids bought penny candy, red hots and little wax bottles filled with sweet, syrupy liquid:

“Part of what made the Camp important to all of us — even to my mother — was that it was a toehold on specialness, a perch on the middle class, where we really had no business belonging. People like us didn’t have summer places. None of our neighbors at home did.”

Growing up in the 1950s with miniature golf, drive-in movies, and souped-up cars, McGrath learned about sex from eavesdropping on “hot rodders” tinkering under their rides. “I concluded that sex, like auto mechanics, must be largely a matter of know-how. You had to understand what went on under the hood.”

By now, you’ve deduced that this memoir is more about the author than his subject, and parts are achingly sad, particularly when McGrath writes about his parents. His mother, who married beneath her social status, appears to have been overly fond of Manhattanites and frequently berated his father for his failings:

“Social class and [his] insufficiency as a provider were ongoing themes in my parents’ marriage.”

It was a sentiment shared by McGrath himself. Looking back, he regrets that his father died “before we could get over being disappointed in each other.” He fantasizes about grabbing his dad’s arm and going for a sail, which is reminiscent of “Field of Dreams,” the film about a son who builds a baseball diamond and bleachers to reconnect with his father: “Build it and they will come.”

Here enters the other Chip, the cheerful summer friend who never disappoints. Together, the two men while away their days golfing and fishing and sailing. They make regular trips to the dump to scavenge discarded clubs; in the evenings, they barbecue and drink “brewskis” with their wives. In 30 years, there’s never a cross word between them.

McGrath goes long and deep on sailing and devotes pages to his beloved Beetle, the last mass-produced wooden boat still being sold in America. “The joy of this never gets old for me,” he writes, “the flutter of the sail, the slap of the bow wave, the burbling of the wake, the tug of the tiller, the lift of the stern quarter as it catches a swell.”

The details of sailing are numerous, sensual even, though he also waxes poetic about birds:

“Gulls everywhere; the cormorants loitering, shrug-shouldered, on rocks and pilings; and the egrets, which perch motionless in trees when they’re not mincing through the shallows.”

McGrath vividly recollects, too, the days he and Chip would meet at the crack of dawn, dragging their used clubs, and drive to five different courses to play 90 holes of golf by 9 p.m., when it was too dark to continue. They did this in tennis shoes because they considered cleats an affectation. The author reflects on these excursions with the pride of Hannibal crossing the Alps with 37 elephants. But personal details of his friendship? Not so much. “It was as if [Chip] had inside him a vast cellar where he could shove away all sorts of worries and bothers,” McGrath writes. “I’m not much better.”

Even when Chip is dying of cancer, in and out of hospitals, unable to walk, relegated to using a cane, then a walker, and finally incontinent and strapped to a bed — even then — the two men talk about the weather and the prospects for the Red Sox.

Shortly before Chip dies, McGrath reaches inside himself and writes a letter, saying for the first time how much their bond has meant:

“I said he was what Romantics used to call a genius loci — the spirit of a place, its embodiment in a person…I wrote down things I had been wanting to say for years…it was too late. And possibly I said too little. This book is what I should have given him.”

Yes, it’s too late for the summer friend, but certainly not for readers.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Ma and Me

by Kitty Kelley

In accepting the 1950 Nobel Prize for Literature, William Faulkner (1897-1962) mourned the state of young writers, who’d “forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself, which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about.”

In accepting the 1950 Nobel Prize for Literature, William Faulkner (1897-1962) mourned the state of young writers, who’d “forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself, which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about.”

If only Faulkner, a white man from Mississippi who never renounced his own racism, could meet Putsata Reang, a gay American woman born in Cambodia whose memoir, Ma and Me, contains all that Faulkner championed in writing — “the old verities and truths of the heart, the universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed.”

Faulkner created a fictional universe (Yoknapatawpha County) to find the truths of “love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice”; Reang finds those truths in the nonfiction she writes about coming to America as a refugee.

“Put,” as her family calls her, was bundled in her mother’s arms at the age of 1 as her parents and six older siblings escaped from Phnom Penh in 1975 before Cambodia fell to the Communist Khmer Rouge. Making the trip to America aboard a ship, Put’s mother carried her malnourished, half-dead baby on deck, frantic to find a doctor who might speak Khmer. Instead, she ran into the ship’s captain, who crisply informed her that, if her child died during the voyage, she’d have to throw the dead body overboard because “we are so over-crowded here…[and] the corpse will spread disease to everyone else.”

Such a burial was abhorrent to a Buddhist mother, so Ma re-consecrated herself to keeping her baby alive, telling Put years later how many times she had come so close to dying. “Out of all my kids, you were the weakest. You were the smallest of all. You were the hardest to take care of.”

Sponsored by two local churches, the Reangs found their way to Corvallis, Oregon, where they arrived with an extended family of 15 — two parents, seven children, one grandparent, and various cousins, aunts, and uncles:

“We were the talk of the town — the first Cambodians to settle amid the city’s corn and fruit fields and its thirty-five thousand mostly white residents.”

Life in America became a series of painful accommodations for the family: to a new language, to new people, to poor-paying migrant jobs picking berries every season. For the children, there was the obligation “to show gratitude to our parents for their quiet sacrifice.”

Reang felt an even greater debt than her siblings because her mother had saved her life. She writes starkly that “I hate my father” because of his cruelty, which may be why she poured so much love into her mother. “[M]y need for Ma was vast…I felt…as if my mother and I were one. Her dreams were my dreams. Her fears were my fears…I refused to go anywhere far from Ma.”

Growing up as a tomboy wearing her brothers’ clothes, Reang was in her 40s before she could publicly acknowledge her sexual identity, once described by Lord Alfred Douglas in a letter to Oscar Wilde as “the love that dare not speak its name.” Ma was horrified when her daughter confessed to being queer, and Reang was heartsick, knowing she “had become the thing I was most afraid of: a disappointment in my mother’s eyes.”

When Reang decided to marry April, the woman she loved, she had the full support of her siblings, but her parents, deeply shamed by what they viewed as an abomination, refused to attend the wedding. The family’s honor within their Cambodian community had been sullied, their reputation ruined.

In this memoir, Reang writes like a flower blooms — beautifully. She describes “sun-plumped blueberries” and “mud-caked knees” and someone who “limp walks” to see “seaplanes splash-land.” Flying into Cambodia on her first return to her country of birth, she’s mesmerized by what she sees:

“Endless acres of rice paddies spread out like squares of carpet patched with seams of irrigation ditches, and the golden spires of pagodas jutted up from between palm trees with fronds dancing in the breeze, lighting and rising like helicopter blades — a land cut through with the purest light.”

While Reang remains psychologically divided as a Cambodian living in America, a homosexual living in a heterosexual world, and a daughter disowned by her beloved mother, she finds peace. “I had believed that Ma and I were so close that we were fused together,” she writes. “I did not know I could exist separate from her, that I could have dreams of my own rather than live out the dreams she had for me.”

William Faulkner would tip his hat to such a writer. He hoped that his Nobel acceptance “might be listened to by the young men and young women already dedicated to the same anguish and travail, among whom is already that one who will someday stand where I am standing.” Putsata Reang, born decades after Faulkner’s speech, might just be a contender.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books