Book Review

Strong Passions

by Kitty Kelley

The title of this book is a clever double entendre. Strong Passions refers to the scandalous divorce of a 19th-century couple named Strong, whose ruptured marriage scars their families and sears their social standing. The first few pages offer a who’s who of high society à la Edith Wharton. In fact, Barbara Weisberg introduces her narrative by quoting from Wharton’s short story “A Cup of Cold Water,” tantalizing readers with the promise of prose from the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction (in 1921, for The Age of Innocence).

The title of this book is a clever double entendre. Strong Passions refers to the scandalous divorce of a 19th-century couple named Strong, whose ruptured marriage scars their families and sears their social standing. The first few pages offer a who’s who of high society à la Edith Wharton. In fact, Barbara Weisberg introduces her narrative by quoting from Wharton’s short story “A Cup of Cold Water,” tantalizing readers with the promise of prose from the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction (in 1921, for The Age of Innocence).

Caveat emptor: Wharton’s only connection to the story told in this book is that she is 2 years old and living in New York City at the time the marital travesty unfolds between Peter Remsen Strong and Mary Emeline Stevens Strong.

The first part of this melodrama reads like a social history of the mid-1800s, when travel by ship from New York to Le Havre took three weeks, and “gentlemen” of a certain class enjoyed gambling houses, cafes, and bordellos while a few — very few — “ladies” traveled abroad. (And when they did, they were always chaperoned and shopped in Paris for “fabulous wardrobes.”)

Such details anchor the story in its era, but without much access to diaries, journals, or letters, Weisberg tells her tale in unsatisfying hypotheticals: “[Mary] would have imagined herself in the roles of wife and mother”; “She might have been eager to hear”; “Her wedding night surely was revelatory”; “Her activities…in an affluent household most likely included”; “She most likely feared.”

Weisberg, whose first book was Talking to the Dead: Kate and Maggie Fox and the Rise of Spiritualism, informs readers in this work that breastfeeding reduced the chance of pregnancy and was considered in the 19th century a form of birth control, which, the author “supposes,” is why Mary refused to wean her third daughter a few months after she was born. That baby, Edith, dies of influenza at 14 months old. On the day of the baby’s funeral, Mary, in a distraught state, admits to her husband that she’d been having an affair with his widowed brother, Edward, who conveniently enlists to fight for the Union in the Civil War. Oh, and P.S.: Mary is five months pregnant, but neither she nor Peter knows by whom.

Determined to salvage his marriage, Peter insists that his wife terminate the pregnancy. To do so, he visits his “alleged” mistress, who happens to be a “mid-wife” renting one of his properties on Waverly Place, where she advertises herself as a “woman doctor.” The author explains this is “a euphemism for a woman who did abortions.” Readers are then treated to several pages on abortion in the 1800s, as well as on adultery, the only basis for divorce in New York until 1922.

Pages later, Peter moves back to his mother’s estate in Newtown, Queens, with his elder daughter, Mamie, and sues his wife for divorce on grounds of adultery. Mary counter-sues, claiming her husband forced her to have an abortion at the hands of an abortionist with whom he was having an affair. Mary then runs away with their younger daughter, Allie. The scoundrel brother of the humiliated husband remains at war, safe from the drama.

Weisberg has presented a legitimate scandal by 19th-century standards: adultery, abortion, and abduction. “Because of the social relations and the position of the parties, and the singular charges and counter charges,” reported the New York Times, “no case before our courts for many years has attracted greater attention.”

Unfortunately, the story becomes more tabloid pottage than Wharton-esque prose. An appropriate comparison might be Mark Twain’s definition of “the difference between the almost right word and the right word” as the difference between a lightning bug and lightning.

Without conclusive evidence of what happened, the author, like the 19th-century journalists covering the case, had more questions than answers: “Where was Mary? Had she kept her little one safe? Had she indeed committed the dreadful offenses of which she was accused? Was she a victim? A seductress?” And where was the errant brother, Edward, in this “near-biblical tale of fraternal betrayal”?

After a six-week trial — the author devotes a dense, detail-laden chapter to each week — the reader is exhausted. The jury does not reach a unanimous verdict, and so Mary, who never appears in court, remains Peter’s lawfully wedded wife. At this point, patience expires, along with sympathy for either party — the wronged husband seeking revenge and the adulterous wife who escapes with her younger child.

Months later, Mary’s attorneys sue for lawyers’ fees and alimony, and the court rules in her favor. Then, in a magnanimous change of heart, Peter, “desirous of…avoiding the scandal of a second public trial,” petitions the court to provide tuition and other money to care for Allie until her 18th birthday. After six years, the divorce is finalized. Peter resumes his life as a gentleman of society, while Mary, ostracized by that society, remains in France with her daughter.

Weisberg insists in her afterword that Strong v. Strong is relevant social history, and on that point, she may be correct. But her attempt to weave the Civil War, the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the Constitution, and the 1868 impeachment of President Andrew Johnson into her protracted narrative proves to be “more lightning bug than lightning.”

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

The Counterfeit Countess

by Kitty Kelley

I approach Holocaust memoirs with knee-bending respect: for the survivors who recall the atrocities they suffered during World War II so that we will never forget, and for the historians who document man’s inhumanity to man. In The Counterfeit Countess, Elizabeth B. White and Joanna Sliwa tell the story of a Polish mathematics professor who hid her identity as Janina Mehlberg (nee Pepi Spinner) when she fled the Jewish ghetto of Lwów, Poland, and reinvented herself as Countess Janina Suchodolska hundreds of miles away in Lublin, where she saved thousands of fellow Jews from annihilation.

I approach Holocaust memoirs with knee-bending respect: for the survivors who recall the atrocities they suffered during World War II so that we will never forget, and for the historians who document man’s inhumanity to man. In The Counterfeit Countess, Elizabeth B. White and Joanna Sliwa tell the story of a Polish mathematics professor who hid her identity as Janina Mehlberg (nee Pepi Spinner) when she fled the Jewish ghetto of Lwów, Poland, and reinvented herself as Countess Janina Suchodolska hundreds of miles away in Lublin, where she saved thousands of fellow Jews from annihilation.

Lublin was headquarters of Aktion Reinhard, the largest SS mass-murder operation of the Holocaust, during which 1.7 million Jews in Poland were slaughtered. German-occupied Poland was effectively ground zero for Hitler’s “final solution”; the place where the majority of the war’s Jewish victims perished; and home to some of the Third Reich’s most notorious concentration camps, including Auschwitz, Chelmno, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, and Majdanek. The latter, with its seven gas chambers, two wooden gallows, crematorium, and 227 outbuildings, was among the largest of Poland’s extermination factories — holding 250,000 prisoners — and is the focus of this book.

The authors are unsparing in describing the unrelenting and unrelieved miseries inflicted by the Nazis in decimating the Jewish population of Poland, which had the largest concentration of Jews in Europe in 1939 — 3.5 million then, fewer than 20,000 today. It becomes almost numbing to read of the killing of so many Jews, Roma (gypsies), and others at the hands of the Germans and their minions.

Nor do the authors spare the survivors, including the countess and her husband, also a professor, who abandoned their Jewish family and friends and assumed new identities as Polish Christian aristocrats in order to escape the Nazis’ brutal plans. The countess understood the animal-like desperation of humans to survive, but it’s only at the end of the book that the authors share excerpts from her unpublished memoir, in which she writes:

“What would a mother do in the face of the impossible choices put to her? There was one who, with her daughter, hid in the wardrobes of her apartment during a raid. They found her daughter, but not her. The child sobbed and screamed for her mother to save her. The mother kept silent, and survived. I know this from the mother herself who, sobbing out her story, wished herself dead instead of condemned to live with this memory.

“Another mother hid with her son in a bunker…Her son ventured out at the wrong time; he was seized and shot right there. The mother heard and remained silent.”

The countess withholds judgment on these impulses to survive, “however grim and unbearable the knowledge may be…Because while physical and psychic tortures broke many, some reacted with what one can only call moral grandeur. I know some…who helped their fellow sufferers at the cost of their own lives, who confessed to others’ ‘crimes,’ who willingly chose death over a degrading life. So, the murder of goodness was not thorough, and this fact, too, must be reported.”

The voice of the countess is so powerful that one wishes the academic co-authors, accomplished as they may be in assembling statistics and geographical details, had allowed her to tell the story in her own words, and then, perhaps, buttressed her account with their prodigious research from Holocaust museums and libraries in the U.S., Canada, Argentina, Uruguay, Germany, and Poland. Although the countess’ memoir concentrates only on what she saw and learned about human nature within the terrible crucible of occupied Poland, her words, her thoughts, and her recollections are enough to lead her story.

A small, cropped photo on the cover of the book shows the countess as a young woman with dark, shiny hair parted in the middle and pulled tightly back behind her ears in the era’s fashionable buns. Yet her biographers barely mention her appearance until 200 pages in, when they quote someone describing her as “small, dark and bright-eyed with massive braids of black hair wound round her head.”

Only in the epilogue do we get her husband’s description of her as “more than ordinarily pretty, very feminine in her style.” Aha. Now we understand how the countess — with her imposing title and good looks — was able to entice so many Nazi guards into waving her through concentration-camp gates without always examining the truckloads of food and collapsible milk urns stuffed with contraband medicine she was delivering to prisoners.

After the war, she returned to her roots as mathematician Josephine Janina Bednarski Spinner Mehlberg and immigrated to Canada with her husband. In 1961, they moved to the U.S. and became American citizens. Before “the counterfeit countess” died in 1969, she returned to Majdanek, writing in her memoir:

“I had achieved less than I had hoped, but I tried, and my efforts had made a difference, so my life had made some difference…Then I thought of those who had been broken, physically and morally, who had betrayed other lives in the hope of saving their own. Of them I spoke…None of us has the right to sit in judgment on them…There is nothing left to do for them but to remember. And in the way of my ancestors intone ‘Yisgadal, v’yiskadash,’ the Kaddish for the dead, and like the real Countess Suchodolska, ‘Kyrie Eleison, Christe Eleison.’ We will remember.”

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

After Elizabeth

by Kitty Kelley

After Elizabeth purports to be the first life-saving buoy tossed to a drowning monarchy. “We’ve been conning ourselves,” writes author Ed Owens, a Brit now living in France. “Just as historians of the (royal-backed) Commonwealth have revealed it to be a hollow organization…the monarchy exists as a kind of screen on to which the UK public has been encouraged to project ideas of perpetual national greatness that simply don’t bear the weight of scrutiny.”

After Elizabeth purports to be the first life-saving buoy tossed to a drowning monarchy. “We’ve been conning ourselves,” writes author Ed Owens, a Brit now living in France. “Just as historians of the (royal-backed) Commonwealth have revealed it to be a hollow organization…the monarchy exists as a kind of screen on to which the UK public has been encouraged to project ideas of perpetual national greatness that simply don’t bear the weight of scrutiny.”

No knighthood for this young man, who announces he’s “under 40” and part of the generation most opposed to “a pampered royal elite.” In reassessing royalty, Owens writes:

“Given its loss of real-world economic and geopolitical power, Britain has comforted itself by focusing on a rear-view mirror that offers a romantic rose-tinted vision of past glories.”

Claiming that “opinion poll after opinion poll” revealed more than half of the country was uninterested in the coronation of King Charles III on May 6, 2023, Owens writes that peak viewership was “just 20 million, roughly two-thirds the size of the audience that tuned in for Queen Elizabeth’s funeral. This was less than one third of the entire UK population.” The author recognizes, as do the royals, that the greatest threat to the crown is not its loudest critics but rather its slow slide into irrelevance.

Despite the 2,300 guests invited to Westminster Abbey to witness Charles’ coronation, the ceremony may have disappointed the son who does not attract his mother’s masses. Swathed in an ermine-trimmed red velvet robe, satin sash, and diamond-encrusted crown, the 75-year-old king looked like he was playing dress-up in the queen’s closet. On that particular day, the St. Edward’s crown itself became a problem. “We practiced putting it on and securing it down twice a week over four months,” the archbishop of Canterbury told the New York Times recently. “It’s a wobbly old thing.”

While the Most Rev. Justin Welby addressed the literal problem of securing the crown on the king’s head, Owens addresses the figurative problem of getting rid of the “wobbly old thing.” But his arguments in this book are themselves too wobbly to be of much concern to the House of Windsor. Royalists will be relieved to learn that for all the author’s talk of “a new kind of democratic kingship,” Owens still intends to crack a knee to the king, whereas Republicans in the U.K., still a minority, seek to replace the monarchy with an elected head of state. No crowns, no curtsies.

For U.K. Republicans, this means a clean sweep of the British class system with its dukes, marquesses, earls (counts), viscounts, and barons. Sitting atop this stratification of British society today is Charles Philip Arthur George — king of the United Kingdom and 14 other commonwealth realms — whose net worth is conservatively estimated to be $747 million, with a real estate portfolio valued at $21 billion, most of which is tax-exempt and hidden from the public.

Trying to straddle the royalist-Republican divide, Owens proposes a “Monarchy Act” that would put in writing the role of the crown in constitutional politics. This is how he attempts to explain his convoluted proposition:

“Although the Monarchy Act could be introduced as part of a much wider codification of the constitution if there was support for it, it could just as easily exist as part of the hybrid constitution (partly written, partly unwritten) that currently exists in Britain, where some parts of government have their function articulated clearly in writing.”

Whew!

Presently, Britain has no fully written constitution, and getting one in the aftermath of Brexit seems as likely as blue birds flying over the white cliffs of Dover. Yet the author suggests that King Charles III, who’s waited decades to wear the crown, might voluntarily initiate a public discussion on the future of the monarchy and seek to diminish his own imperial role.

This challenges credulity — somewhat like expecting a death-row prisoner to willingly oil the coils of the electric chair — yet Owens insists that if the monarchy doesn’t radically reinvent itself, which “will require root-and-branch reform,” Britain will devolve into a republic. The author leaves no doubt about how distasteful that would be.

Readers of this dense book full of rambling run-on sentences might be well advised to catch the final six episodes of The Crown and dwell in the bubble of fashion and money and gossip and intrigue that defines the same House of Windsor young Ed Owens seeks to reform and rehabilitate.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

The Postcard

by Kitty Kelley

An “un-put-down-able” book is like a double rainbow — rare and oh so magical. Titles like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles, Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter, The Godfather by Mario Puzo, The Thorn Birds by Colleen McCullough, Strange Fruit by Lillian Smith, and The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton are just a few such double rainbows that stir the soul much like the spine-tingling stories of Stephen King, John le Carré’s Cold War spy thrillers, and the works of Walt Whitman, America’s poet emeritus.

An “un-put-down-able” book is like a double rainbow — rare and oh so magical. Titles like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles, Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter, The Godfather by Mario Puzo, The Thorn Birds by Colleen McCullough, Strange Fruit by Lillian Smith, and The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton are just a few such double rainbows that stir the soul much like the spine-tingling stories of Stephen King, John le Carré’s Cold War spy thrillers, and the works of Walt Whitman, America’s poet emeritus.

Now comes another un-put-down-able book, The Postcard, by French writer Anne Berest, who defines her Holocaust work as an “auto-hybrid,” an “autobiography of sorts,” and “a true novel” that she’s wrapped in bits of fiction to protect the grandchildren, still alive, who had nothing to do with the unconscionable crimes committed by their relatives during World War II.

Berest begins her story with a mysterious postcard featuring Paris’ Palais Garnier opera house sent to her mother. On the back are the names of her mother’s grandfather, grandmother, aunt, and uncle — all annihilated in Auschwitz in 1942. No note. No signature. No return address. Most disturbing to Berest was the image of the Opéra Garnier — the central locale of the Nazis during their occupation of France.

“We were terrified [when we received that postcard],” Berest told the New York Post. “For us French people that’s a very strong symbol.” The surge in antisemitism and xenophobia throughout Europe added layers of menace to the card. “All the signs on the postcard were signs of a threat.”

First published in France in 2021 as La carte postale, Berest’s book tells the story of her grandmother, Myriam (nee Rabinovitch) Picabia, who escaped the round-up of Jews in Paris by hiding in the woods. She was later rescued, hidden in the trunk of a car, and driven 50 miles north of Marseilles, where she and her fiancé — and her lover — joined the Resistance, ran messages, and translated illicit BBC broadcasts.

“This [ménage à trois] is actually the part of the book that my mother didn’t really want me to write,” Berest says. “But this sort of love triangle, this three-person romantic arrangement, was one of the most striking things to me…After writing so many difficult pages about dark, dark times [this romance] was a kind of light in the book.”

The Postcard takes readers on the author’s painful journey toward her roots. Having been raised in a secular household, Berest was unfamiliar with Jewish rituals. Yet she was surprised by the frisson of familiarity she felt attending a Passover Seder at the home of her boyfriend. During the evening, he mentioned to guests that Berest’s daughter had recently been wounded by an antisemitic remark at school. When asked what she did about it, Berest admitted that she hadn’t addressed the matter. One of the guests snapped, “The truth, as far as I can tell, is that you’re only Jewish when it suits you.”

The remark stung but eventually pushed Berest into “the dark, dark times” of excavating her roots and claiming her heritage. At the end of her search, she writes:

“All I can tell you is that I’m the child of a survivor. That is, someone who may not be familiar with the Seder rituals, but whose family died in the gas chambers. Someone who has the same nightmares as her mother and is trying to find her place among the living.”

The book, translated flawlessly into English by Tina Kover, became an international bestseller and was longlisted for the Prix Goncourt, France’s most distinguished literary prize. But one of the judges, Camille Laurens, pilloried Berest’s book in Le Monde as “the Holocaust for Dummies.” Laurens slammed the author, young and pretty, as “an expert on Parisian chic” who entered a gas chamber with “her big red sole [Christian Louboutin] clogs.” France’s public radio station rebuked the reviewer for “unheard-of brutality,” and the Left Bank started buzzing.

It turned out that Laurens’ romantic partner, too, was being considered for the Prix Goncourt, also for a book about the Holocaust. He had dedicated his work to a certain “C.L.” who, when criticized for her cruelty, claimed she’d sledgehammered Berest’s book “before” she knew it was longlisted for the prestigious prize. Putride. Vireux. Nauseabond.

The Goncourt immediately dropped both works from consideration and revised its rules, now stating that no lover, relative, spouse, or partner of a member of the jury can be considered for the prize once awarded to Marcel Proust, André Malraux, Simone de Beauvoir, Romain Gary, and Marguerite Dumas.

After that literary storm, The Postcard was blessed with its own double rainbow — widespread critical praise and commercial sales. Both richly deserved.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Passionate Mothers, Powerful Sons

by Kitty Kelley

During the pandemic, Charlotte Gray scored a win for women. The Canadian author spent her lockdown days examining the lives of two American mothers previously disregarded by male historians as mere accessories to their world-conquering sons. The result is a feminist take on the women, who’ve been derided and diminished for decades: Jennie Jerome Churchill, once depicted as a fashion-crazed flibbertigibbet, and Sara Delano Roosevelt, dismissed as a wealthy harridan.

During the pandemic, Charlotte Gray scored a win for women. The Canadian author spent her lockdown days examining the lives of two American mothers previously disregarded by male historians as mere accessories to their world-conquering sons. The result is a feminist take on the women, who’ve been derided and diminished for decades: Jennie Jerome Churchill, once depicted as a fashion-crazed flibbertigibbet, and Sara Delano Roosevelt, dismissed as a wealthy harridan.

“They’ve been shoehorned into harmful stereotypes,” writes Gray, “and rarely been portrayed in a sympathetic light since their deaths. In fact, their sons’ biographers often disparage them — it is as though the Great Men of History must spring like Athena, fully formed from the head of Zeus, without tiresome interventions from their mothers.”

Most of those who’ve examined these so-called “great men” are themselves men, including respected biographers William Manchester, author of the three-volume The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill; Andrew Roberts (Churchill: Walking with Destiny); Alan Brinkley (Franklin Delano Roosevelt); and H.W. Brands (Traitor to His Class: The Privileged Life and Radical Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt).

Now comes a reassessment of both in Passionate Mothers, Powerful Sons: The Lives of Jennie Jerome Churchill and Sara Delano Roosevelt. Gray, who’s written 12 literary nonfiction books, is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. Relegated to mining secondary sources of previously published material, she nonetheless manages to bring a compelling view to the life stories of two mothers who influenced the world through their sons.

Both women were unicorns, each one of a kind but complete opposites of each other. Jennie Jerome, who wed Lord Randolph Churchill, was the most famous American heiress to cross the Atlantic and marry a title during the Gilded Age of 1870-1914. As Lady Churchill, she kept her status through three marriages while enjoying numerous dalliances with paramours said to include a Serbian prince, a German nobleman, several British aristocrats, and the prince of Wales, who admired American women because “they are livelier, better-educated, and less hampered by etiquette…not as squeamish as their English sisters.” Jennie became a favorite of the latter, the future King Edward VII, and used her golden contacts to enhance her son’s prospects. As Winston said, “She left no wire unpulled, no stone unturned, no cutlet uncooked.”

Once Winston married, his mother lost her premier place in his life. But whereas Jennie loathed the role of grandmother, Sara Delano Roosevelt reveled in it. On one occasion, when FDR’s two youngest sons were disciplined by having their pony taken away, Sara bought each little boy a horse. Naturally, all the Roosevelt grandchildren adored their grandmother, leaving their mother embittered. As Eleanor Roosevelt wrote years later, “As it turned out, Franklin’s children were more my mother-in-law’s children than they were mine.”

Also unlike Jennie Churchill, Sara Roosevelt enjoyed lifetime access to elite society and did not color outside the lines of proper protocol. Following her husband’s death, the dowager aristocrat donned widow’s weeds and never considered remarriage. Living like a vestal virgin, Sara dedicated herself to her only child, the future American president, following him to Harvard and living near campus so she could see him for dinner once a week. When Franklin married, his mother enlarged her homes at Campobello, in Manhattan, and at Hyde Park to accommodate his growing family, providing them with nannies, maids, laundresses, cooks, and drivers. She even advised her son professionally, counseling him after he won his first political appointment: “Try not to write your signature too small…so many public men have such awful signatures, and so unreadable.”

Spoiled and indulged by adoring mothers, Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt possessed galloping self-confidence that bordered on arrogance and made each insufferable to colleagues. As Churchill said when he returned from the Boer Wars a national hero, “We are all worms, but I do believe that I am a glow-worm.”

Not surprisingly, each of these two egoists had little regard for the other. As FDR told Joseph Kennedy after appointing him U.S. ambassador to the Court of St. James, “I have always disliked [Churchill] since I went to England in 1918 [as assistant secretary of the Navy]. He acted like a stinker then, lording it over all of us.”

Fortunately, their relationship changed when Churchill became prime minister of Great Britain, Roosevelt was commander-in-chief of the United States, and the world was at war. But their closeness — and, indeed, FDR’s prominent place in history — might never have evolved had it not been for the fierce intervention of Sara Delano Roosevelt.

Returning home from London in 1918, Franklin had come down with Spanish flu exacerbated by double pneumonia. His mother and his wife met his ship in New York and had him carried on a stretcher to Sara’s home on East 65th. Street. As the orderlies struggled to make Roosevelt comfortable, Eleanor began unpacking his suitcases and there found love letters from Lucy Mercer. Devastated, she marked that moment as life-changing: “The bottom dropped out of my world.”

Tearfully confronting her husband — as did his mother — Eleanor offered to grant him a divorce. Sara roared back in horror. Furious at her son’s moral lapse, yet fearing the shame a divorce might bring to the family, she declared that if he left his wife, he’d be leaving her as well — and that included Sara’s vast fortune, which supported him, his five children, and his future political prospects. Franklin made the pragmatic decision to remain in the marriage; Eleanor permanently moved out of their bedroom.

Back in London, after years of being chased by unscrupulous money-lenders and litigious creditors, Jennie Jerome Churchill died a grotesque death in 1921. At age 67, she fell down a staircase while wearing a new pair of high heels. “Life didn’t begin for her on a basis of less than forty pairs of shoes,” said Winston’s secretary about Jennie’s unchecked extravagances and staggering debts. Within days of breaking her ankle, gangrene set in, necessitating amputation of her leg above the knee. Lady Churchill soon slipped into a coma and expired, leaving Winston inconsolable. For the rest of his days, he kept a bronze cast of his mother’s hand on his desk.

Sara Roosevelt, however, lived a long and enviable life. She saw a beloved son crippled by polio rise to become president of the United States three times. At his third inauguration, she proudly proclaimed herself “a mother of history,” saying that few mothers ever lived to see their sons elected once. “Why, when you read history it seems as if most of the Presidents didn’t have mothers, the way they fail to appear in the accounts.” At the age of 86, Sara wrote to her son:

“Perhaps I have lived too long, but when I think of you and hear your voice I do not ever want to leave you.”

Alas, Roosevelt’s adoring mother took her final leave on September 7, 1941, and within four years, as he was starting an unprecedented fourth term as chief executive, her “precious son” would follow her at the age of 62 after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage at the Little White House in Warm Springs, Georgia.

In this provocative biography, Charlotte Gray bestows revisionist interest on two “passionate mothers” whose “powerful sons” proved themselves worthy of the maternal love and devotion showered on each.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Letters for the Ages

by Kitty Kelley

Nazi troops began studying English phrasebooks to prepare for their invasion of Great Britain. France had fallen under Germany’s Blitzkrieg in June 1940, following the capitulation of Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. Swastikas papered Paris to welcome Hitler.

Nazi troops began studying English phrasebooks to prepare for their invasion of Great Britain. France had fallen under Germany’s Blitzkrieg in June 1940, following the capitulation of Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. Swastikas papered Paris to welcome Hitler.

Across the Channel, Great Britain’s prime minister addressed his country on the radio and summoned them to what he pronounced would be their finest hour: “Hitler knows he will have to break us in these islands or lose the war. If we can stand up to him all Europe may be freed, and life for the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands.”

Over the airwaves, Winston Churchill spoke eloquently as he inspired his nation. Behind the scenes, he churned with rage, lashing out at everyone. In desperation, his privy council begged his wife to intercede.

Clementine Churchill knew that her husband would pay attention to a letter, and so she labored over one, rewriting her pages twice before she found the right words. “My Darling Winston,” she began, “I hope you will forgive me if I tell you something I feel you ought to know.” Then, with care and consideration, Mrs. Churchill, self-described as “loving devoted & watchful,” told her ferocious husband that he’d been “rough, sarcastic and over-bearing” to his colleagues and subordinates.

Prim as a schoolmarm disciplining an unruly student, Clementine instructed urbanity, kindness, “and if possible Olympic calm.” She further recommended that the prime minister, who had the power to “sack anyone & everyone,” except for the king, the archbishop of Canterbury, and the speaker of the House of Commons, curb his “irascibility & rudeness. They will breed either dislike or a slave mentality — (Rebellion in War time being out of the question!).”

Unfortunately, Letters for the Ages, a treasure trove of Churchill’s correspondence, doesn’t contain the lion’s response to the lioness, but its editors claim to “be fairly certain that he listened to his ‘devoted & watchful’ cat.” Clementine kept her letter as part of the historical record, as an insight into their relationship, and as an important glimpse into the pressures of wartime leadership.

Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (1874-1965) wrote 40 books in 60 volumes and won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1953. Trumpeted by YouTube as “Britain’s Greatest Prime Minister,” he served in that office from 1940-1945 and again from 1951-1955. His speeches, especially his wartime broadcasts, inspired a nation under German bombardment and are considered among the most powerful ever delivered in the English language.

So, a compilation of his correspondence promises to be a cornucopia of insights into the man who once introduced himself by saying, “We are all worms, but I do believe I am a glow worm.” The letters he wrote as a child to his mother, his nanny, and his stern father reveal young Winston to be stubborn, willful, and rebellious but utterly persuasive in getting his way — characteristics that would define him as a world leader.

At the age of 13, the adolescent wanted nothing more than to be sprung from boarding school in Brighton to return to London for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. Young Winston wrote home that he particularly longed to see “Buffalow [sic] Bill,” the Wild West show of William F. Cody. His teacher denied his request to be excused, so he drafted a letter for his mother, Lady Randolph (Jennie Spencer Churchill), to sign in order to release him from school.

“My dear Mamma,” he wrote without punctuation, “I shall be very disappointed, disappointed is not the word I shall be miserable, after you have promised me, and all, I shall never trust your promises again. But I know that Mummy loves her Winny much too much for that. Write to Mrs. [sic] Thomson and say that you have promised me and you want to have me home…I am quite well but in a ferment about coming home it would upset me entirely if you were to stop me.” He closed by signing: “Love & kisses I remain yours as ever Loving Son (Remember) Winny.”

The next day, “Winny” wrote another letter, again entreating his mother: “Please, as you love me, do as I have begged you.” Not surprisingly, “dear Mamma” agreed.

As fascinating as the letters in this book are the photographs, particularly the one showing 7-year-old Winston in a sailor suit, plucky and cocksure, with one hand on his hip and the other resting on an ornate chair. He looks directly at the camera as if to say, My presence is your privilege.

cocksure, with one hand on his hip and the other resting on an ornate chair. He looks directly at the camera as if to say, My presence is your privilege.

Interestingly, one of the most iconic Churchill photographs is not included here, although the photographer, Yousef Karsh, was Canadian and considered a British subject in 1941 when he took his famous photo during the prime minister’s wartime visit to Ottawa. Karsh was allowed only two minutes, and as he rushed to set up, his subject lit up. He asked Churchill to put down his cigar because the smoke interfered with the film, but Churchill refused. So, moments before Karsh snapped his lens, he grabbed the cigar out of the great man’s mouth.

“By the time I got back to the camera,” he recalled, “he looked so belligerent he could have devoured me.” Yet when Churchill later saw the forceful image, he complimented the photographer, “You can even make a roaring lion stand still to be photographed.”

This book of letters will find its audience within the International Churchill Society (which offers annual memberships for $100), as well as at the National Churchill Library and Center at George Washington University in Washington, DC, at Churchill College in Cambridge, at Churchill’s War Rooms in London, and at Churchill’s Chartwell estate in Kent. There and elsewhere, the lion still roars.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

August Wilson

by Kitty Kelley

The celebrated playwright August Wilson (1945-2005) was born Frederick August Kittel Jr. to a Black mother and a white father who abandoned his wife and six children. The fourth child and namesake son was called Freddie, but when his father deserted the family, Freddie took his mother’s surname and became August Wilson. The fatherless child never discussed the scars of being abandoned, but the loss permeated his life’s work.

The celebrated playwright August Wilson (1945-2005) was born Frederick August Kittel Jr. to a Black mother and a white father who abandoned his wife and six children. The fourth child and namesake son was called Freddie, but when his father deserted the family, Freddie took his mother’s surname and became August Wilson. The fatherless child never discussed the scars of being abandoned, but the loss permeated his life’s work.

Wilson adored his mother, Daisy, and desperately sought her approval, but she wanted him to be a lawyer and remained unimpressed by his poetry or even his award-winning plays. “You be a writer when you get something on television,” she told him. The day his play “The Piano Player” aired on CBS’ Hallmark Hall of Fame, February 2, 1995, Wilson gazed up to heaven and thought, “Look, Ma. I did it.” Reflecting on his mother’s passing, the heartbroken son explained:

“It is only when you encounter a world that does not contain your mother that you begin to fully comprehend the idea of loss and the huge irrevocable absence that death occasions.”

Although biracial, Wilson identified as Black and resented any attempt to be defined otherwise. He became irate when Henry Louis Gates Jr. questioned his Blackness in the New Yorker by writing, “He neither looks nor sounds typically Black — had he the desire he could easily pass — and that makes him Black first and foremost by self-identification.” As a playwright, however, Wilson subscribed to the creed of W.E.B. Du Bois, who promoted the four fundamental principles of “real Negro theater”: 1) About us 2) By us 3) For us 4) Near us.

In each of the 10 plays that comprise the Pittsburgh Cycle, Wilson — hailed as “theater’s poet of Black America” — portrays the African-American experience in a different decade of the 20th century. They all opened on Broadway, two of them posthumously:

“Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” 1984

“Fences” 1987

“Joe Turner’s Come and Gone” 1988

“The Piano Lesson” 1990

“Two Trains Running” 1992

“Seven Guitars” 1996

“King Headley II” 2001

“Gem of the Ocean” 2004

“Radio Golf” 2007

“Jitney” 2017

Wilson insisted his plays be produced and performed only by Black artists and denounced “color-blind casting,” asserting that “Blacks have always, historically, been the custodians for America’s hope.” Yet as Patti Hartigan writes — gloriously — in August Wilson: A Life, the first major biography of the man, Wilson’s genius was singular and his work universal, winning him two Pulitzer Prizes and 29 Tony Awards.

While Hartigan, a former theater critic for the Boston Globe, genuflects to Wilson’s monumental talent, she does not spare him his faults. Hypersensitive to slights and given to explosive rages unleashed on waitresses or workmen below him in status, Wilson was an errant husband who married three times and took countless lovers. His first priority in life — above family and friends — was his work. “For him,” Hartigan states, “writing was a force necessary for survival.”

As a high-school dropout with an IQ of 143, young Wilson haunted the aisles of Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Library, where he was relegated to the “Negro section.” He spent hours reading Langston Hughes, Ralph Ellison, and Paul Laurence Dunbar. He described the neighborhood in which he grew up as “an amalgam of the unwanted,” filled with a mishmash of Greeks, Jews, Syrians, Italians, Irish, and Blacks, “each ethnic group seeking to cast off the vestiges of the old country, changing names, changing manners…bludgeoning the malleable parts of themselves. Melting into the pot. Becoming and defining what it means to be an American.”

While Wilson described himself as a “race man,” and all his characters are Black, their stories of pain and sorrow and joy and resentment resonate as shared human verities. “There are always and only two trains running,” he once said. “There is life and there is death. Each of us rides them both.”

Wilson believed that African Americans needed to keep their history alive and cherish their heritage — complete with all its ancestors and all its ghosts. Maintaining that Black culture is unique and worthy of celebration, he sought out Black directors and dramaturges who understood his mission: to celebrate the lives of ordinary Black people.

This was lost on Bill Moyers when he interviewed Wilson in 1988 for the PBS series A World of Ideas. Moyers claimed that Blacks in America needed to embrace the mores of the dominant white culture in order to succeed and suggested that Blacks ought to aspire to the kind of bland middle-class life depicted on The Cosby Show. Those familiar with Wilson’s hair-trigger temper expected him to lay into the obtuse host, but knowing he was on national television, Wilson remained calm and simply remarked that Cosby’s show “does not reflect Black America to my mind.”

Moyers further humiliated himself by asking, “Don’t you grow weary of thinking Black, writing Black, being asked questions about Blacks?” Again, Wilson responded with restraint:

“How could one grow weary of that? Whites don’t get tired of thinking white or being who they are. I’m just who I am. You never transcend who you are. Black is not limiting. There’s no idea in the world that is not contained by Black life. I could write forever about the black experience in America.”

When Cosby gave a speech castigating Black youth for “stealing Coca-Cola” and “getting shot in the back of the head over a piece of pound cake,” Wilson blasted him. “A billionaire attacking poor people for being poor,” he told Time Magazine. “Bill Cosby is a clown. What do you expect? I thought it was unfair of him.”

Hartigan mentions in her author’s note that she had to paraphrase many of Wilson’s intimate letters, early plays, and poems because his estate declined to authorize their use in this book. Still, thanks to prodigious research and significant interviews, including notes from the days she spent with Wilson in 2005 for a Boston Globe Magazine profile, she has crafted a spectacular biography of “a truth teller” whom she eloquently describes as “a griot who accurately depicted the ordinary lives of honorable people whose stories were ignored by the mainstream culture.”

As William Styron once wrote, “A great book should leave you with many experiences and slightly exhausted at the end. You live several lives while reading.” Patti Hartigan has written just such a book about an illustrious playwright.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Taking Things Hard

by Kitty Kelley

Success is said to be a bitch goddess who sprays splendor like a shooting star in the night sky. Many writers spend their lives chasing her, most to no avail. John Keats, Franz Kafka, Henry David Thoreau, Emily Dickinson, Herman Melville, Edgar Allan Poe — all died without ever experiencing her starshine.

Success is said to be a bitch goddess who sprays splendor like a shooting star in the night sky. Many writers spend their lives chasing her, most to no avail. John Keats, Franz Kafka, Henry David Thoreau, Emily Dickinson, Herman Melville, Edgar Allan Poe — all died without ever experiencing her starshine.

Not so F. Scott Fitzgerald. The goddess wrapped him in riches, recognition, and renown at the age of 24 with his first novel, This Side of Paradise. Two years later, in 1922, he published The Beautiful and the Damned, and she showered him with international fame and prestige. Fitzgerald became the trumpeter of the Roaring Twenties, an era of champagne wealth and flapper frivolity that lasted as long as a bubble before it burst and plunged the country into years of depression. The bitch goddess took flight just as the trumpeter was embarking on the novel that would eventually become his legacy. He would not live long enough to savor its rewards.

Fitzgerald’s life has been chronicled in numerous biographies, letters, essays, scrapbooks, memoirs, notebooks, documentaries, and films, a challenging cornucopia facing any modern-day author who aspires to examine the life that produced what many claim is the United States’ greatest novel. “If you want to know what America’s like, you read The Great Gatsby,” said Professor John Kuehl of New York University. “Fitzgerald is the quintessential American writer.”

Most scholars sniff at Fitzgerald’s short stories, but Robert R. Garnett, professor emeritus of English at Gettysburg College, has chosen to limn the writer’s life through some of those 180 tales in Taking Things Hard: The Trials of F. Scott Fitzgerald. The title springs from Fitzgerald’s assessment of himself as a scribe. In a letter to Ernest Hemingway, he wrote, “Taking things hard…That’s [the] stamp that goes into my books so that people can read it blind like brail.”

Hemingway agreed. “We are all bitched from the start, and you especially have to be hurt like hell before you can write seriously.”

Garnett concurs. “For Fitzgerald, the emotions of love and loss were far more compelling than any idea,” he writes. “[He] was not an intellectual.”

Starting with one of “the worst things F. Scott Fitzgerald ever wrote for publication,” Garnett pulls out a “deservedly unknown” 1935 short story published in Redbook, which he describes as “wooden, simplistic, puerile, awash in cliché and banality, with ninth-century colloquial rendered in a hodgepodge of cowboy-movie, hillbilly, and detective novel.” (Here, one is tempted to steer the professor to The Elements of Style, in which Strunk and White advise using nouns and verbs rather than adjectives and adverbs.)

The year 1935 is crucial to Garnett’s book — and to Fitzgerald’s life — because it marks “the crack-up,” when the magic had drained from the writer’s golden world and everything turned to dross. He was institutionalized for alcoholism, and his descent was chronicled in a 150-page, single-spaced journal that Garnett feels “is the most valuable single source for any period of his life.” The journal was written by Laura Guthrie, who met Fitzgerald when both were recuperating in Ashville, North Carolina. During that time, she became his confidant, advisor, and crying towel.

Fitzgerald later wrote three Esquire articles about his “crack-up,” which one biographer described as “sheer brilliance.” Garnett dismisses this as sheer nonsense. “Far from brilliantly written, the articles are littered with the cliches and tired metaphors of slipshod writing — ‘the dead hand of the past,’ ‘up to the hilt,’ ‘a place in the sun,’ ‘not a pretty picture,’ ‘burning the candle at both ends,’ ‘sleight of hand,” and ‘beady-eyed men.’” Garnett further fillets Fitzgerald’s series as “filled with vagueness, obscurity, facile generalizing, non sequiturs, and padding (a random diatribe against Hollywood, for example).”

Tinseltown was hell for Fitzgerald, who’d moved there in 1937, hoping to resuscitate his career and recapture vanished glory. Still married to Zelda, at the time institutionalized with schizophrenia, he moved in with Sheilah Graham, the nationally syndicated Hollywood gossip columnist, and lived with her until he died of a heart attack in 1940.

On the subject of Graham, Garnett sounds a bit puritanical, alluding to her “amorous past” and dismissing her as “ambitious, enterprising, attractive, hardworking, shrewd, and not over-scrupulous, she had climbed from…poverty to become a chorus girl, then journalist.” The professor judges her as “too conventional, vin ordinaire, to generate much emotion [from Fitzgerald] beyond comfort and gratitude.”

How interesting it might’ve been for an accomplished scholar such as Garnett to have examined Graham and her ascent in the world in comparison to that of Jay Gatsby in Fitzgerald’s masterpiece. Both working-class characters of questionable backgrounds and no education came to represent the American Dream. An analysis of such by an English professor could’ve added insight and scholarship to the corpus of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Alas, a missed opportunity.

Chances are, the bitch goddess will not be spraying splendor on Garnett’s treatise, but the professor can take comfort in the legion of Fitzgerald aficionados who will find some nuggets within Taking Things Hard to be worthy of gold.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

King: A Life

by Kitty Kelley

They said one to another

Behold here cometh the Dreamer

Let us slay him

And we shall see what will become of his dreams.

– Genesis 37:19-20

These words are carved into the cement plaque that rests outside room 306 of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. They mark the place where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. The dreamer’s death transformed his murder site into a shrine that now houses the National Civil Rights Museum, where King’s life continues to inspire, drawing thousands of visitors every year.

These words are carved into the cement plaque that rests outside room 306 of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. They mark the place where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. The dreamer’s death transformed his murder site into a shrine that now houses the National Civil Rights Museum, where King’s life continues to inspire, drawing thousands of visitors every year.

Scholars and historians have long explored the legacy of the Baptist minister from Georgia who preached a gospel of nonviolence. Deservedly, many King biographies have won prestigious prizes, among them Taylor Branch’s magisterial trilogy: Parting the Waters, Pillar of Fire, and At Canaan’s Edge. Additional tributes to King include I May Not Get There with You by Michael Eric Dyson; Bearing the Cross by David J. Garrow; Let the Trumpet Sound by Stephen B. Oates; Death of a King by Tavis Smiley; The Promise and the Dream by David Margolick; and The Sword and the Shield by Peniel E. Joseph.

Now comes Jonathan Eig with King: A Life, which promises “to recover the real man from the gray mist of hagiography.” Regrettably, says the author, “In the process of canonizing King, we’ve defanged him…[but] King was a man, not a saint, not a symbol.” In removing the mantle, Eig presents here an orator of soaring rhetoric who unapologetically plagiarized his speeches, saying his goal was to move audiences. Even King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech seems to have had its origins in Langston Hughes’ poems “I Dream a World” and “Dream Deferred.”

Misappropriating others’ work is a grievous sin for scholars, a “bad habit,” Eig writes, that King started in high school and continued as a graduate student at Crozier and later at Boston University, where he earned his Ph.D. with a dissertation that contained more than 50 sentences lifted from someone else’s work. By contrast, readers will note how generous Eig is to his own sources, giving previous biographers their due and quoting many by name in his text, not simply relegating them to chapter notes in the back of the book. Just as noteworthy is Eig’s appreciation for all who contributed to King: A Life; he lists each name under “Acknowledgements: Beloved Community.”

In this biography, his sixth book, Eig writes like an Olympic diver who jackknifes off the high board, slicing the water without a ripple. He performs with sheer artistry, like Picasso paints and Astaire dances. In unspooling the life of King, Eig presents a complicated man who attempted suicide twice; who was plagued by clinical depression so deep it required hospitalization; who chewed his nails; and who gave up the “true love” of his life, a white woman named Betty Moitz, because he realized, with her, he would never be accepted as a preacher in Black churches. The late Harry Belafonte, who himself married a white woman, told Eig that King never stopped talking about Moitz, and King’s mentor in graduate school described him after the break-up as “a man with a broken heart,” adding, “he never recovered.”

Although he married Coretta Scott and had four children with her, King pursued many women throughout his life. While Eig is unsparing about those extramarital affairs, he writes gently: “King’s busy schedule of travel also afforded him opportunities to spend time with women other than Coretta.”

The author also draws interesting similarities between King and John F. Kennedy, both of whom indelibly marked their era:

- Both were influenced by powerful (and philandering) fathers.

- Both enjoyed a privileged lifestyle above their contemporaries.

- Both were accused of plagiarism.

- Both experienced discrimination (JFK as an Irish Catholic; King as a Black man).

- Both excelled as public speakers.

- Both were assassinated.

King was particularly threatened by the never-made-public tape recordings FBI director J. Edgar Hoover ordered, turning federal agents into bloodhounds and instructing them to install bugs wherever King traveled. Hoover distributed copies of the recordings, which contained evidence of “unnatural sexual acts,” to President Lyndon Johnson, White House officials, and journalists in order to undermine King’s credibility. To further ensure his ruin, Hoover met with a group of woman journalists and declared King the country’s “most notorious liar.”

King reportedly wept over the slur to his life’s work but managed a masterful response to the press:

“I cannot conceive of Mr. Hoover making a statement like this without being under extreme pressure. He has apparently faltered under the awesome burden, complexities and responsibilities of his office. Therefore, I cannot engage in a public debate with him. I have nothing but sympathy for this man who has served his country well.”

By opposing the “immoral” war in Vietnam, King, who’d received the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, drew the unremitting ire of Johnson. As Eig writes, King’s “conscience would not allow him to cooperate with an advocate and purveyor of war.” Infuriated, Johnson never forgave the man who’d given his presidency its three greatest legislative achievements: the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

While Eig reveals the flawed man behind the myth, Martin Luther King Jr. still stands tall and strong enough to shoulder Shakespeare’s words from “Measure for Measure”:

They say best men are molded out of faults,

And, for the most, become much more the better

For being a little bad

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

(Color photo of Martin Luther King Jr. by Stanley Tretick, 1966, from Let Freedom Ring.)

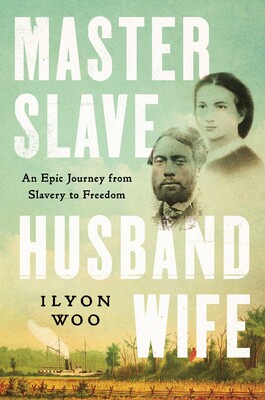

Master Slave Husband Wife

by Kitty Kelley

The morning after Martin Luther King Day 2023 marked the release of Ilyon Woo’s extraordinary Master Slave Husband Wife: An Epic Journey from Slavery to Freedom. Reviewers received advance proofs from the publisher with a note from Bob Bender, executive editor of Simon & Schuster, extolling the book and wondering why the story of Ellen and William Craft was not yet a staple of American history.

The morning after Martin Luther King Day 2023 marked the release of Ilyon Woo’s extraordinary Master Slave Husband Wife: An Epic Journey from Slavery to Freedom. Reviewers received advance proofs from the publisher with a note from Bob Bender, executive editor of Simon & Schuster, extolling the book and wondering why the story of Ellen and William Craft was not yet a staple of American history.

Soon, Mr. Bender. Soon.

The Crafts’ story is no ordinary slave narrative, although “ordinary” hardly describes the harrowing attempts that desperate human beings made in 18th- and 19th-century America to flee slavery’s choke-hold. Hordes of bounty hunters laid in wait to capture fugitives and drag them back to their owners in chains. Few made it to freedom, which is why the Crafts are so extraordinary: They took white supremacy and turned it upside down and sideways in order to escape in plain sight, executing one of the boldest feats of self-emancipation in U.S. history.

Ellen Craft was born to a white father, James Smith, who also enslaved Ellen’s 18-year-old mother. Smith’s wife gave Ellen — a living, daily reminder of her husband’s infidelity — as a wedding present to their daughter, Eliza, when she married Robert Collins of Macon, Georgia. Being half-sisters, the girls had grown up together, and Ellen, looking as white as Eliza, was trusted as a “house slave” to sew and cook and take care of the children. While in Macon, Ellen fell in love with William Craft, an enslaved man who lived nearby. Together, they schemed to run away at the end of 1848, more than a decade before the Civil War.

They plot every detail of their escape with strategic precision. Ellen, an expert seamstress, begins sewing the costume she will wear to disguise herself as a white man in failing health traveling to Philadelphia for medical treatment, accompanied by “his” slave. She makes baggy plus-fours — the stylish men’s trousers of the day — a white silk shirt, a black cravat, and a custom-designed jacket that only a gentleman of means could afford. Traveling as “Mr. Johnson,” she wears dark green glasses and a “double-story” black silk hat “befitting how high it rises, and the fiction it covers.”

She applies poultices to her face and wraps her right hand in bandages and a sling to explain why she can’t sign travel documents at several stops. (Being enslaved, Ellen was not allowed to learn how to read or write.) The dark-skinned William, acting like an obsequious slave, helps Ellen on and off trains and buses and boats, attending to “his” every need during their journey. At each stop, William ushers his infirm “master” to “his” first-class cabin before retiring to the colored quarters, where he eats from a slop bowl and sleeps standing up.

From Macon, the train rolls into Savannah, “City of Shade and Silence,” and site of the largest slave market in America, known as “the Weeping Time.” With staggering audaciousness, master and slave continue by steamship to Charleston, South Carolina, where, Woo writes:

“All along the harbor were tall ships and steamers, weighing the waves with their cargo; golden crops of rice, bales of cotton, chinoiserie — and chained below decks, the enslaved, a major commodity in this international port. There were slave sales near the docks, in shops, closer inland, and by the Custom House, which hosted the city’s largest open-air slave market on its north side, as Ellen knew. The sight was so disturbing to foreigners (and therefore bad for business) that, in a few years, the city would pass laws to hustle the trade indoors.”

Days later, the Crafts arrive in Richmond, Virginia, a veritable police state since Nat Turner’s Rebellion in 1831, still considered the most significant slave uprising in American history. “Mr. Johnson” and “his” slave rumble over Aquia Creek to Washington, DC, and through a dark channel to Fort McHenry in Baltimore, where Francis Scott Key, himself an enslaver, wrote “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Three more stops, and the couple finally cross the Mason-Dixon Line and reach Philadelphia, the so-called City of Brotherly Love, where even the Quakers drew lines to separate the “colored” benches in their meetinghouses.

Master Slave Husband Wife hits all the marks of a masterpiece: unforgettable characters, stirring conflicts, breathtaking courage, and a pulsating plot wrapped around an unforgiveable sin. Author Woo is a rare breed of writer — a scholar with a Ph.D. who’s nevertheless mastered the art of narrative nonfiction. She tells this story with incomparable skill, following the Crafts from Philadelphia to Boston, where they become icons of the abolitionist movement, traveling the antislavery lecture circuit. But the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 forces them to keep on the run. By law, they’re still enslaved and deeply in danger, especially once Robert Collins, Ellen’s owner back in Georgia, hires bounty hunters to track them down.

No longer safe in the U.S., the Crafts move to England for several years, where they bring up six children and publish an account of their escape, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom. When Abraham Lincoln signs the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, the Crafts feel safe enough to return home, first to South Carolina and then to Georgia, where they start a school and live out the remainder of their days.

Ellen and William Craft embody the human drive to relentlessly pursue freedom. Ilyon Woo, in Master Slave Husband Wife, honors their story with grace and humanity, and presents her publisher with a phenomenon.

Stand by, Mr. Bender. Stand by.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books