Blog

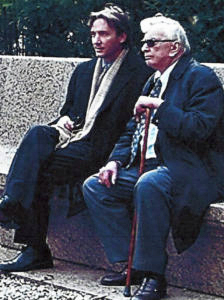

Kitty Kelley and Sy Hersh

Photo 9/4/21

Dust to Dust

by Kitty Kelley

“Never offend an enemy in a small way,” Gore Vidal once wrote. The prickly writer, who thrived on making enemies, may soon be spewing venom from six feet under. Eight years after his death, he is scheduled to cast shade on his nemesis, William F. Buckley, Jr., in a new play by Alexandra Petri, called Inherit the Windbag. The play is in virtual rehearsals right now, at Washington, D.C.’s Mosaic Theatre Company, but when a stage version opens, likely next spring, the groundskeeper at Rock Creek Cemetery would be well advised to keep an eye on Section E, Lot 293 ½, where Vidal’s ashes are buried. Vidal outlived Buckley by four years, but never forgave the man who called him a “queer” in a 1968 televised debate. When Buckley died, Vidal cheered, “RIP WFB—in hell.”

The odyssey that Vidal’s remains took before their interment was no less dramatic. The writer spent many hours negotiating the details of his grave. From his villa in Ravello, Italy, he stipulated that his ashes be placed near an Augustus Saint-Gaudens sculpture commissioned by the historian Henry Adams, in memory of his wife, who committed suicide. This monument is the most visited site in the eighty-acre park, just across the street from the former Old Soldiers’ Home, where President Lincoln summered during the Civil War. Vidal, who made millions in real estate, understood its first three commandments: location, location, location.

details of his grave. From his villa in Ravello, Italy, he stipulated that his ashes be placed near an Augustus Saint-Gaudens sculpture commissioned by the historian Henry Adams, in memory of his wife, who committed suicide. This monument is the most visited site in the eighty-acre park, just across the street from the former Old Soldiers’ Home, where President Lincoln summered during the Civil War. Vidal, who made millions in real estate, understood its first three commandments: location, location, location.

Vidal also instructed that he and Howard Austen, his partner of fifty-three years, be buried near the grave of Jimmie Trimble, a blond athlete whom Vidal met when both were students at St. Albans School. Trimble was killed at Iwo Jima, but he lived for the rest of Vidal’s life in fevered fantasies. By placing his own remains between those of Trimble and Adams—a descendant of two American Presidents, who was buried next to his wife—Vidal was, as he wrote, “midway between heart and mind, to put it grandly.”

Like a pharaoh gilding his tomb, Vidal continued making legacy preparations: he commissioned his biography to be written in his lifetime by Fred Kaplan, who accompanied Vidal and Austen to the cemetery in 1994, to complete their final interment papers. Kaplan signed as their witness and later published a well-received book (Gore Vidal: A Biography), but, when the Times dismissed Vidal as a “minor” writer in its review, Vidal fired off a letter to the editor, blaming Kaplan. He claimed, preposterously, that he thought he’d commissioned the biographer Justin Kaplan, not Fred Kaplan. (Kaplan was not the only writer to be pulverized by Vidal. The three saddest words in the English language, Vidal once said, were “Joyce Carol Oates.”)

Not long after Kaplan finished the book, Vidal moved his papers (almost four hundred boxes’ worth) from the University of Wisconsin’s Center for Film and Theater Research to Harvard University. Months before he died, at the age of eighty-six, he added a codicil to his will, leaving his entire thirty-seven-million-dollar estate to Harvard, which triggered a blizzard of lawsuits after his death and delayed his burial for years. “At the end, Gore was drinking bottles of Macallan Scotch around the clock, having hallucinations, in and out of hospitals and well into dementia,” his half sister Nina Straight said. She was the first to sue the Vidal estate, to recover a million dollars that she said she had loaned her brother to fund his lawsuit against Buckley.

“The end was awful, just awful,” her son Burr Steers said. “He was no longer Gore—just a deranged old man, killing himself with booze.” Steers, who had taken possession of his uncle’s ashes, filed suit, too, claiming ownership of Vidal’s house in Los Angeles, which had been left to him in a previous will. Later, Steers sued to have the estate trustee, Andrew Auchincloss, his third cousin, removed for “reckless misconduct,” claiming that Auchincloss had tried to defraud him.

Vidal, who liked to say that, after fifty, litigation replaces sex, probably would have enjoyed the flurry of lawsuits. After numerous depositions and document dumps, Straight dropped her suit, Steers lost the L.A. house, and Auchincloss remained trustee of the estate. How the ashes made it from Los Angeles to Rock Creek Cemetery, where they were interred in 2016, in a small private ceremony, is a mystery. Steers’s attorney, Eric M. George, had no comment, citing “a strict confidentiality clause.” For someone who thrived on publicity to be buried with no fanfare seems pathetic, but a public Facebook page, GoreVidalNow.com, indicates that there is at least one keeper of the literary banshee’s flame. The site is managed by Michelle Gore, who is married to a third cousin of Vidal’s and who visited Vidal in Italy. “Gore, I miss you each day,” she writes. A sweet coda for a curmudgeon. ♦

Gore Vidal was interred in Rock Creek Cemetery on June 24, 2016 in a small private ceremony.

Posted by GoreVidalNow.com on Wednesday, July 20, 2016

Published in the print edition of the New Yorker, August 31, 2020 issue, with the headline “Dust to Dust.” Online “Can Gore Vidal Find Rest in His Final Resting Place?“

(See also “Gore Vidal’s Final Feud” by Kitty Kelley, Washingtoninan November 2015.)

Photo of Gore Vidal with nephew Burr Steers in Rock Creek Cemetery courtesy of Burr Steers

BIO Podcast

Kitty Kelley spoke with BIO member John A. Farrell in February 2020 in Washington, D.C.

Kitty Kelley spoke with BIO member John A. Farrell in February 2020 in Washington, D.C.

Part I (26:53):

Part II (26:26):

John A. Farrell’s website: http://www.jafarrell.com/

Biographers International Organization: https://biographersinternational.org/

BIO Podcasts: https://biographersinternational.org/podcasts/

Part I URL:

https://biographersinternational.org/news/podcast/podcast-episode-45-kitty-kelley-part-i/?fbclid=IwAR0N2CMGj5Fzg5bY4Rx1VsXkGCd2HHri1K0jOKHbgf8x4uJlIwGliZWGlFI

Part II URL:

https://biographersinternational.org/news/podcast/podcast-episode-46-kitty-kelley-part-ii/?fbclid=IwAR1xJI97oOu5YbQSP2_4M6dl1DABV7g12Wnzcjp2MpdbU4fr5tHY3683kOg

BIO Board of Directors

- Linda Leavell, President (2019-2021)

- Sarah S. Kilborne, Vice President (2020-2022)

- Marc Leepson, Treasurer (2019-2021)

- Billy Tooma, Secretary (2020-2022)

- Kai Bird (2019-2021)

- Deirdre David (2019-2021)

- Natalie Dykstra (2020-2022)

- Carla Kaplan (2020-2022)

- Kitty Kelley (2019-2021)

- Heath Lee (2019-2021)

- Steve Paul (2020-2022)

- Anne Boyd Rioux (2019-2021)

- Marlene Trestman (2019-2021)

- Eric K. Washington (2020-2022)

- Sonja Williams (2019-2021)

Christmas at the White House

by Kitty Kelley

Christmas at the White House this year dazzles with gold ribbons and sparking lights, fir boughs, fir wreaths and the delicious scent of 33 fir trees. Crystal stars sparkle above the red-carpet colonnade in the East Wing to welcome the 7,000 lucky people who received invitations from the president and first lady.

Once guests present their credentials and pass through security — which entails three Secret Service stops, two police dog sniffs and one pat-down with a metal wand — they walk to the driveway to enter the people’s palace, where everything shines and glistens in the public rooms.

Topiary trees are festooned in big red velvet bows, mantels are banked in red roses and doorways lead into rooms of wonder. The gold Vermeil Room pays homage to first lady Jacqueline Kennedy, who established the White House as a museum. Her portrait by Aaron Shikler hangs on the wall, a lovely elusive image.

Over the fireplace is a smiling Lady Bird Johnson and across the hall is the White House library, containing 2,700 books. It appears to have been decorated by elves who know that Reading Is Fundamental. Tiny books are tasseled to trees and wrapped in ribbons around the mantel is a beguiling tribute to literacy. Miniature books, leather-bound with tiny gold titles, hang from the room’s Christmas tree.

Visitors gasp aloud as they wander into the East Room, pose in the Green Room, exclaim over the China Room, sigh in the Blue Room. The Red Room delights with its creative décor of children’s games — playing cards cascade from the trees with dice, jacks, tiddlywinks and Scrabble squares spelling the message of the season: “PEACE … LOVE … JOY.”

The State Dining Room pays tribute to America with a gigantic gingerbread White House (200 pounds of dough slathered with 25 pounds of frosting) surrounded by the country’s landmarks. The display showcases the genius of White House chefs, who have conjured confectionary creations of the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, the Space Needle in Seattle, Mount Rushmore in Keystone, South Dakota, the Alamo in San Antonio, the Gateway Arch in St. Louis, the Statue of Liberty in New York and the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia.

The sumptuous tour culminates in the Grand Foyer, where carolers sing amid a crush of fir trees — 20 feet tall — all dusted with snow and gold bulbs and sparkling lights. Emblazoned high on the wall is the Great Seal of the United States with the words, “E Pluribus Unum,” Latin for “Out of many, one.”

As everyone leaves the White House, aides hand each guest a small red package filled with Hershey’s kisses and a lovely laminated pamphlet entitled “The Spirit of America Christmas at the White House 2019.”

Originally published in The Georgetowner December 18, 2019

A London Theater Tour

by Kitty Kelley

Molly Smith, artistic director of Arena Stage, led a troupe of D.C. theater hounds to London recently to see British theater — inside and out. “Since Arena is celebrating its 70th anniversary as the largest theater company in the U.S. dedicated to American plays and playwrights, this seemed like a good time to see what the Brits are doing,” she said.

Arena’s weeklong tour offered a full course of culture: six plays, two operas, three art galleries, a private tour of Tate Modern, coffee with an international art collector in his Cadogan Square flat, lunch in the House of Lords, fish and chips at a gastropub, a trip to Shakespeare’s birthplace at Stratford-upon-Avon and many flutes of champagne. Throughout, there were nannies the equal of Mary Poppins and brainiac guides, who seemed to have earned six degrees apiece from Oxford.

We were chauffeured to and from Brown’s Hotel in the heart of Mayfair to see plays that baffled the imagination and gripped the heart. We walked the City of London on a magical tour to see the original Roman settlement that became the famous “Square Mile,” where residences “now cost a minimum of $8 million.”

From the Old Vic to the Young Vic, we explored behind the scenes, touching the props (see Martha Dippell kissing a stuffed rhino), pulling the curtains and walking the boards. We even discovered a “non-religious church” in Islington, not far from the Almeida Theatre,that “believes not in God, but in good.” (For proof, visit new-unity.org.)

A highlight of the tour was meeting Kwame Kwei-Armah, artistic director of the Young Vic, who many theatergoers will remember from his years at Center Stage in Baltimore, from 2011 to 2018.

“Now I’m back home in England and a bit of an anomaly — a black man in British theater,” he said. “In 2005, I became only the second black Brit to have a play staged in the West End, and until 18 months ago I was the only black artistic director in the western hemisphere … We have a long way to go.”

From his experience living in the U.S. and the U.K., Kwei-Armah said the British are obsessed with class distinctions and refuse to discuss racial issues, whereas Americans are decades ahead of the British on race but avoid the subject of class. “You are in denial, and out of fear of talking about the working class and the underclasses, you put all your college-educated into the middle class.”

Because British theater is partially subsidized by the government, ticket prices in the U.K. are lower than in the U.S. ($15 to $50 in the U.K. compared to $100 and above in the U.S.) and attract younger audiences. “But in both the U.S. and the U.K., 70 percent of all theatergoers are women,” said Kwei-Armah. “Because of our government subsidy, we can take plays to prisons and refugee centers where they’d never have access to high-quality theater or any theater at all. We go to them.”

Kwei-Armah turned deadly serious on the subject of Brexit. “We are in the midst of a rather profound nervous breakdown here, and Brexit will nearly collapse theater in London and eviscerate all our touring companies,” he said. “We are living in suspense and don’t know what’s going to happen, but we do know it’s going to be nasty, very nasty.”

The Arena Stage troupe returned to Washington, D.C., thoroughly energized by their London theater adventure, which all pronounced “ab fab” (Brit-speak for “absolutely fabulous”).

Originally published in The Georgetowner December 4, 2019

What It’s Like to Be Kitty Kelley

Originally published in Washingtonian October 2019

I’ve been in DC since, let’s see . . . since Abraham Lincoln was President! I came to help with Senator Eugene McCarthy’s Foreign Relations Committee mail for a six-week stint, but I ended up in his Senate office and stayed four years. I remember that his personal secretary, who looked like she had been on the job 102 years, took one look at me and said, ‘Can she type or take shorthand?’ McCarthy replied, ‘We don’t ask the impossible of anyone around here.’ I thought, This guy has got a great sense of humor.

When I left the Hill in 1968, I became the researcher for the Washington Post editorial page. After two fabulous years at the paper, I got a book contract to investigate the beauty-spa industry. Since I weighed three pounds less than a horse, I signed fast and saddled up to visit every fat farm in the country. I got myself down to pony size, and the book probably sold 14 copies—all to my mother.

Then I backed into writing biographies, beginning with Jackie Oh! I love the genre, but writing an unauthorized biography brings its challenges. The subjects I’ve chosen are extremely powerful public figures who’ve had a vast impact on our lives and are fully invested in their images. Consequently, the blowback can be considerable.

I remember when my Nancy Reagan book came out in 1991, my late husband, John, who was courting me at the time, took me to Bice, then a real hot spot in DC. As we walked in, a man stood up and started yelling, ‘Booooo! Get that bitch out of here! Boo! Boo!’ John turned around to see who the guy was yelling at. I knew and looked straight ahead, praying not to cry. The man kept yelling, everyone turned to look, and then a woman on the other side of the restaurant started yelling, ‘No, no—she’s brave!’ The two of them went at each other, and the restaurant suddenly looked like tennis at Wimbledon, turning from one side to the other. The maître d’ brought us to a table, and John buried himself in the wine list. Then a guy from the middle of the room threw his napkin on the floor and headed for our table. I thought for sure we were goners. He spread out his arms and embraced me: ‘Kitty, you don’t know me, but I’m going to stand here until this stops.’ It was Tony Coehlo, the majority whip in the House of Representatives. I introduced him to John, who said, ‘Congressman, you go in the will.’ John told me later he was going to propose over dinner but was so flummoxed by what happened, he put it off for 24 hours.

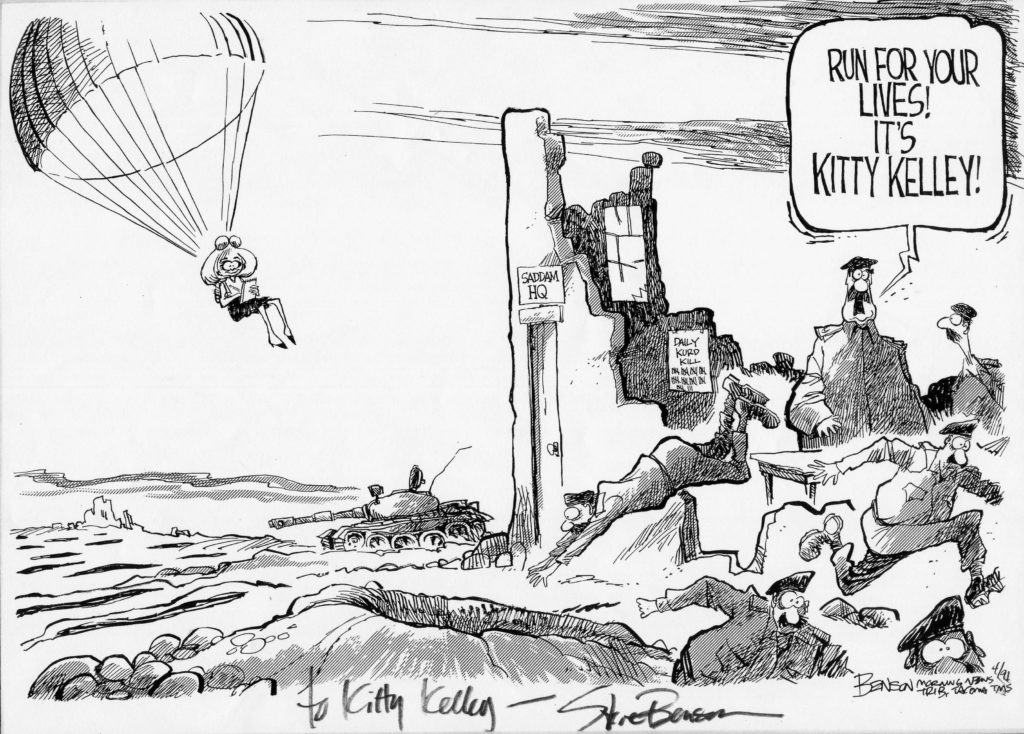

My Bush-family book drew fire from the White House, the Republican National Committee, and the GOP leader in the House of Representatives. I framed all the cartoons and hung them where they belong—in the loo. My favorite is the bubble-headed blonde in Chanel shoes parachuting into Saddam Hussein’s bunker, scattering the armed guards, who yell, ‘Run for your lives! It’s Kitty Kelley!’

I don’t write about just anybody. I only choose huge figures who have manufactured a public image. I’m fascinated to find out what they’re really like. I’m not doing another great big bio simply because, at this moment in time, I don’t want to know what anyone out there is really like. Certainly not Trump. Melania? Oh, definitely not.

I’ve already done seven New York Times bestsellers. I can’t say that I loved doing them, but I sure loved finishing them.

At the Leon Levy Center for Biography

Reconciliation

by Kitty Kelley

Mélisande Short-Colomb knows her begats. Three years ago, she received a Facebook message from a genealogist, asking if she was related to the Mahoney family of Baton Rouge. Like a Biblical scholar ticking off Old Testament lineage, she typed out a list of her forebears—enslaved and free—going back seven generations. The genealogist had struck gold. For months, she’d been searching for descendants of the roughly three hundred slaves who had been sold by the Maryland Jesuits who owned Georgetown College, in 1838, for a hundred and fifteen thousand dollars, to save the school from bankruptcy. With the help of Short-Colomb and her begats, more than eight thousand descendants of these slaves were located. Now Georgetown University is trying to make it up to them. Last month, the student body voted to pay reparations to the heirs.

Short-Colomb, who is sixty-five, with gray hair, is a rising junior at Georgetown. “I’m not just one of the oldest students here and one of the few African-Americans,” she said the other day. “I’m also part of the reconciliation program.” In 2016, the university began offering legacy status—a preference for admission, not a scholarship—to descendants of slaves owned by the Maryland Jesuits. One descendant has graduated, two are in graduate school, and three—including Short-Colomb—are undergraduates. “I’m here to help the Jesuits atone for their sins,” she said, smiling.

and one of the few African-Americans,” she said the other day. “I’m also part of the reconciliation program.” In 2016, the university began offering legacy status—a preference for admission, not a scholarship—to descendants of slaves owned by the Maryland Jesuits. One descendant has graduated, two are in graduate school, and three—including Short-Colomb—are undergraduates. “I’m here to help the Jesuits atone for their sins,” she said, smiling.

Short-Colomb was hanging out in her dorm, Copley Hall. Her room, which she calls her “tiny condo,” has a single bed, a large bathroom with grab rails, and a desk piled with papers, books, and a few crystals. She’s comfortable now, after what she calls the “trauma” of her first semester. “I was overwhelmed by everything that the young white students seemed to take in stride, if not for granted,” she said. “The kids all had the same look—leggings, puffy jackets, athletic shoes, and ponytails.” Short-Colomb, who had worked as a chef for twenty-two years, was used to wearing a uniform. “I didn’t know how to dress for college,” she said. “I looked strange walking around in my blue suède pumps.” That day, she had on a sweatshirt, sandals, and ripped, wide-legged jeans.

Last year, her window looked out on the school’s Jesuit cemetery. She would sometimes end her day watching the sun set over it. “I took a perverse pleasure in having survived the struggle of my ancestors,” she said. “I looked out at those Jesuit tombstones and was unapologetically grateful that they are dead and I am alive.” She admitted feeling bitter when she sees the African-American groundskeepers, knowing that the university had built over the former burial sites of slaves. “No brothers weeding and mowing their grounds,” she said.

The university isn’t bound by the student referendum to pay reparations, but the board of directors is expected to consider the recommendation in June. If it votes in favor, a reconciliation fee of twenty-seven dollars and twenty cents will be added to each undergraduate’s tuition bill. Short-Colomb helped rally the votes. Standing in a grassy quad, she’d announced, into a megaphone, “The dollar amount, symbolic of the two hundred and seventy-two Jesuit slaves sold, is only one-tenth of one per cent of the average tuition per semester.”

The result of the student vote is controversial on campus. Some students say that the university should pay its own reparations rather than make students fund them. International students have objected to paying for a crime that they didn’t commit. To the skeptics, Short-Colomb responds, “You came here voluntarily, and you’ll leave with the prestige of a degree from an esteemed university that would not exist but for the enslaved people who built it.”

Later that day, Short-Colomb cooked a gumbo dinner for her friend Richard Cellini, the founder of the Georgetown Memory Project. Cellini’s venture, which receives no financial support from Georgetown, has identified eight thousand four hundred and twenty-five descendants, more than four thousand of whom are alive. He hopes to locate even more and reunite fifteen hundred families who were separated by the 1838 sale.

Cellini, who describes himself as a “mustard-seed Catholic,” said that he knew very little about slavery or African-American history until a couple of years ago, when students began protesting after a story about the Georgetown slave auction ran in the student paper. “I could not stop thinking about the families ripped apart by that sale whose names had been in the university archives for years,” he said. Ironically, written records exist only because the Jesuits insisted that their slaves be baptized.

“We’ll save your soul while we sell your ass,” Short-Colomb joked.

Originally published in “Talk of the Town” in New Yorker print edition May 20, 2019

10/29/2019 Update on reparations at Georgetown University here.