Blog

Kitty Kelley Dissertation Fellowship

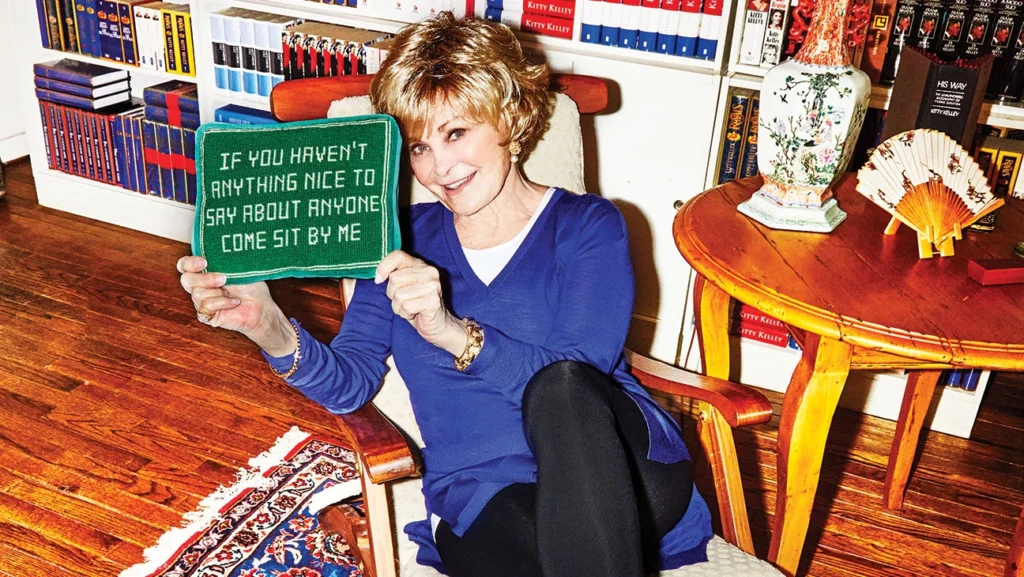

The Kitty Kelley Dissertation Fellowship in Biography will provide $25,000 to a doctoral student who is writing a dissertation in English focused on the life of another person or upon the lives of two or more individuals. This generous fellowship is endowed by Kitty Kelley, a founding member BIO and long-time advocate for biography and biographers, as well as the bestselling author of multiple biographical works where she has displayed courage and deftness in writing unvarnished accounts of some of the most powerful figures in politics, media, and popular culture, including Oprah Winfrey, the Bush Family, the Royal Family, Nancy Reagan, Frank Sinatra, Elizabeth Taylor, and Jackie Kennedy Onassis.

The Kitty Kelley Dissertation Fellowship in Biography will provide $25,000 to a doctoral student who is writing a dissertation in English focused on the life of another person or upon the lives of two or more individuals. This generous fellowship is endowed by Kitty Kelley, a founding member BIO and long-time advocate for biography and biographers, as well as the bestselling author of multiple biographical works where she has displayed courage and deftness in writing unvarnished accounts of some of the most powerful figures in politics, media, and popular culture, including Oprah Winfrey, the Bush Family, the Royal Family, Nancy Reagan, Frank Sinatra, Elizabeth Taylor, and Jackie Kennedy Onassis.

Reflecting on the impact of this new fellowship, BIO Committee Chair Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina remarks, “BIO is delighted to offer this exciting opportunity for a Ph.D. student writing a biography as their dissertation. Kitty Kelley’s generosity in funding a biographical project at the dissertation level will go a long way to encourage the writing of biography at the final stages of academic training. We hope that the fellowship will inspire universities to endorse such projects, which combine the rigor of doctoral research with the art of storytelling.”

Kitty Kelley said of her decision to create this fellowship, “Biography is the art of telling a life story. By exploring the past, we illuminate the present, and enlarge the future. I hope this dissertation fellowship opens a wide world of ideas and imagination coupled with potential and purpose.”

The Kitty Kelley Dissertation Fellowship in Biography will provide $25,000 in financial support so that a doctoral candidate may devote a year to completing a dissertation in the field of biography. A fellow is expected to pursue the dissertation project on a full-time basis during the funding period and must be writing a dissertation in English focused upon the life of another person or upon the lives of two or more individuals. It cannot be fictionalized nor should the focus be primarily autobiographical. It need not cover the entire life of its subject or subjects. Applicants must have completed all course work, passed all preliminary examinations and received approval for a dissertation proposal. Students who have already received a dissertation fellowship are not eligible. The fellowship is open to students in all fields and academic departments, provided that the dissertation is biographical in its methods and focus.

For the fellowship starting September 1, 2025, the deadline to apply will be January 15, 2025, and the winner of the $25,000 scholarship will be announced no later than May 1, 2025. The request for applications is now open. For more information, please visit this link.

Thinkin’ in the Bardo

by Kitty Kelley

George Saunders did not want his tombstone to read, “Here lies a guy who never did what he wanted to do.” So, in 2017, at the age of 59, having mastered the art of the dystopian short story, Saunders secretly began writing his first novel. Four years later, he burst into the literary stratosphere with Lincoln in the Bardo, which earned him the Man Booker Prize. Colson Whitehead, already in that stratosphere, called Saunders’ book “a luminous feat of generosity and humanism.”

In The Tibetan Book of the Dead, the bardo is the interim space between life and afterlife where spirits who’ve not yet reconciled their deaths must remain until they resolve lingering issues with their lives and can proceed to their next incarnation.

“I was raised Catholic, where purgatory is like the DMV,” said Saunders, now a practicing Buddhist, who made his literary bona fides as a comic sci-fi writer and published frequently in the New Yorker. During that time, he was named a MacArthur Fellow (aka a “Genius Grant” recipient), garnered a Guggenheim Fellowship, and won the PEN/Malamud Award for Excellence in the Short Story. In addition, he became a full professor at Syracuse University, where he teaches in the MFA program.

Those prestigious awards seem to hang lightly on Saunders, whose scruffy beard and rumpled jeans make him look a bit impish, rather like a choirboy gone rogue. Politically, he admits to being a liberal (“left of Gandhi, actually”) and acts as comfortable behind a lectern as he is conversing with Stephen Colbert on late-night television.

Saunders recently returned to Washington, DC, to speak at the Library of Congress, where he’d received its 2023 prize for best American fiction. The following day, he led a small troupe of admirers to the marble crypt in Oak Hill Cemetery where Abraham Lincoln’s 11-year-old son, Willie, who died of typhoid fever on February 20, 1862, once lay. Willie became pivotal among the 166 characters Saunders created in his prizewinning novel.

Saunders recently returned to Washington, DC, to speak at the Library of Congress, where he’d received its 2023 prize for best American fiction. The following day, he led a small troupe of admirers to the marble crypt in Oak Hill Cemetery where Abraham Lincoln’s 11-year-old son, Willie, who died of typhoid fever on February 20, 1862, once lay. Willie became pivotal among the 166 characters Saunders created in his prizewinning novel.

Leading the group through the 150-year-old cemetery at the top of Georgetown, Saunders related how the grief-ravaged president rode his horse late at night from the White House to sit in the gated crypt belonging to William Thomas Carroll, where he held the casket of his beloved son. The Carroll mausoleum is the most visited gravesite in the cemetery. In addition to sharing his family’s crypt with the president, Carroll, clerk of the U.S. Supreme Court, also loaned the commander-in-chief his family Bible to be sworn in on as president in 1861. President-elect Barack Obama used that same Bible for his own 2009 swearing-in.

“The thing about a place like Oak Hill…walking through it always makes me feel more alive and more urgent about…whatever it is I’m supposed to be doing down here,” Saunders wrote on his Substack account of the visit. “There’s no ‘we’ and no ‘them.’ There’s just life and then that grand waterfall we all will have to go over.”

During the tour, the cemetery archivist presented Saunders with a circa-1862 key of the type Lincoln would have used to gain entry to the cemetery. (“Do I love this kind of thing?” Saunders wrote later. “You know I do.”) He recalled being transported the first time he visited the gravesite:

“Wow. This really happened. Lincoln, really, for sure, stood here…somehow that made me feel I could and must write the book.”

The publication of Lincoln in the Bardo has bound Saunders to the Georgetown burial ground in ways he never imagined while writing. In addition to the novel’s prizes and plaudits — which include the 2018 Audie Award for audiobook of the year — the Metropolitan Opera has commissioned Missy Mazzoli, an American composer, to create an opera based on Saunders’ book to debut in 2026. A movie is also in the works. “This connects me forever to Oak Hill,” said Saunders.

Later that evening, he spoke in the cemetery’s Renwick Chapel, where Willie’s funeral was held. Standing in front of the huge stained-glass window featuring a giant angel uplifted by iridescent wings, the professor talked about the creative process and how he met the challenge of conjuring spirits to communicate with the anguished Lincoln, who finds the strength amid the graveyard’s clamoring lost souls to rise above his personal sorrow and lead the country through the Civil War. Saunders believes it was that graveside evolution within Lincoln that enabled him to write the Emancipation Proclamation.

“When a writer has a problem, the reader feels it, and then, when the writer identifies and addresses that problem — presto — this feels like originality and innovation,” he told the chapel crowd.

Some writers never get to “presto,” but for those who do, exhilaration awaits. In conveying the magic of creativity, Saunders echoed William Faulkner’s 1950 Nobel Prize address about the writer’s responsibility to create “out of the materials of the human spirit something which did not exist before.” George Saunders did exactly that with Lincoln in the Bardo.

Photo by Laura Thoms

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

1974 All Over Again

Maureen Dowd refers to “Death and the All-American Boy”

New York Times February 24, 2024, Maureen Dowd, “Sex and the Capital City”

June 1974 Washingtonian, Kitty Kelley, “Death and the All-American Boy” (link):

Kitty Kelley’s Endless Generosity

by Holly Smith

Bestselling biographer and all-around excellent literary citizen Kitty Kelley has done it again. Just a few months after her historic donation to Biographers International Organization, Kelley has now given $100,000 to the nonprofit Washington Independent Review of Books in furtherance of our mission to share a love of reading freely and widely, to support full access to books of all kinds, and to introduce readers to authors they might not otherwise meet.

Bestselling biographer and all-around excellent literary citizen Kitty Kelley has done it again. Just a few months after her historic donation to Biographers International Organization, Kelley has now given $100,000 to the nonprofit Washington Independent Review of Books in furtherance of our mission to share a love of reading freely and widely, to support full access to books of all kinds, and to introduce readers to authors they might not otherwise meet.

“Kitty’s is the largest single gift the Independent has ever received, and her generosity honors us beyond words,” says Jennifer Bort Yacovissi, president of the Independent’s board of directors, on which Kelley serves. “By providing a stable base for our current operations, Kitty has given us the gift of breathing room to successfully pursue both new programs and the long-term funding strategies that will carry us well into the future.”

Rather than viewing Kelley’s unrestricted gift as an excuse to ease up on our efforts to bring you the reviews, columns, Q&As, and other features you’ve come to expect, we see it as a challenge to be better, to work harder, and to earn the backing of additional like-minded readers who appreciate what we do.

“We hope Kitty’s belief and investment in our mission inspires others to follow her example,” says Yacovissi. In the meantime, we intend to use the funding we have to continue adding our voice to those championing books and reading — especially now, when so many forces have aligned to silence them.

Holly Smith is editor-in-chief of the Independent.

BIO Award Winner Kitty Kelley’s Speech

Kitty Kelley won the 2023 Biographers International Organization Award. On Saturday, May 20, at the 2023 BIO Conference, it was also announced that Kelley will make a gift of $1 million to BIO, to be given over the course of five years. You can read more about that here.

The following is Kitty’s keynote address:

If I get run over tonight, please make sure that this BIO award leads my obit, because it’ll be the only time that my name shares the same space with Ron Chernow and Robert Caro and Stacy Schiff. But I don’t want to think about obituaries right now. I want to share with you a little bit about the writing life that brings me here today.

I love books and as much as I enjoy fiction, I bend my knee to nonfiction, particularly biography—the art of telling a life story. All kinds of life stories—memoir, authorized and unauthorized biography, historical narrative, or contemporary profiles.

In the last few decades, I’ve written biographies about living icons, a genre that is sometimes dismissed as “unauthorized biography” and, unfortunately, the term is sometimes said as if you’re emptying a bedpan or cleaning up the dog’s mess. Unauthorized biographies are not approved by everyone and rarely appreciated by their subjects. One exception, of course, is the New Testament, which was written by disciples who never knew their subject.

About 40 years ago, I thought I’d died and gone to biography heaven when Bantam Books offered me a grand advance to write the unauthorized biography of Frank Sinatra. I’d written two previous biographies and been robbed on both. On the first one, I didn’t have an agent—which is like driving a car without a steering wheel. On the second, I had an agent straight out of Oliver Twist. You may remember the woman who advised Linda Tripp to advise Monica Lewinsky to save her blue dress. Well, that same woman was once a literary agent who caused about $70,000 in foreign sales to go missing on my Elizabeth Taylor biography. My lawyer was incensed and insisted I sue. I told him to write the agent, say I’d misplaced records, and ask for another accounting. I figured that way she could correct herself and repay the missing monies.

I’m embarrassed to admit that I let this go on for over a year because I just couldn’t believe a literary agent would steal from a client. My lawyer said, “Try to get it into your fat head: She’s not Max Perkins. She’s Ma Barker.”

After 17 months, I finally filed suit. Depositions were taken and the case went to federal court in Washington, D.C. I fully expected her to settle because the evidence was so overwhelming. Instead, the case went to trial and the jury found Ma Barker guilty on all six counts, including fraud. They demanded she make payment on the courthouse steps and even asked for punitive damages.

I suppose the lawsuit was a great victory, because I unloaded a bad agent and got a good one, but I was in no hurry to do another biography. I’d just learned the hard way that there’s no education in the second kick of a mule. I’d undertaken the Elizabeth Taylor biography, hoping to write about the Hollywood studio system that had shaped our fantasies for most of the 20th century. I envisioned weaving that theme into the life story of Elizabeth Taylor, who grew up as a little girl at MGM, and went to school at MGM and . . . married many MGM men. But my plan for this historical narrative soon got buried in Ms. Taylor’s Technicolor life of husbands and hospitals and jewelry stores.

My agent asked, if I were to consider writing another life story, who would be of interest? I said, “Well, the gold ring on the merry-go-round would be Frank Sinatra, because no one’s really done it, and he epitomizes the American dream.” She agreed and that was the end of the subject until a couple weeks later when she called and said she had a generous offer from Bantam Books.

Soon I was back in the biography business, thinking I’d paid my hard luck dues. I’d had a bandit publisher on my first book and a thieving agent on my second. Now was third time lucky. And for a few weeks it was . . . until I was served a subpoena from Frank Sinatra, announcing that he was suing me for $2 million dollars for usurping the rights to his life story. He claimed that he and he alone (or someone he authorized) was entitled to write his life story, and I certainly had not been authorized.

I immediately called my publisher, and Bantam’s legal counsel informed me that I was on my own. “Mr. Sinatra has not sued us,” she said. “He’s sued you, and since you’ve not given us a manuscript, we’re not involved. So, I’d advise you to get legal counsel in California, which is where you’ve been sued and do keep us informed.”

“But I haven’t written a word. I’ve only just begun. My manuscript is years away.”

“We’ll talk then,” she said, before hanging up.

Now, getting sued by a billionaire with Mafia ties concentrates the mind, especially after your publisher leaves the scene. I called my friend, the president of Washington Independent Writers, to commiserate. “I wish we could help you, Kitty, but we’re almost broke,” she said. I assured her that I wasn’t looking for money—just moral support. “Well, in that case, let me get on the horn.” She contacted several writers’ groups, including the Authors Guild and PEN and the American Society of Journalists and Authors, and Sigma Delta Chi, and the National Writers Union. Days later, they held a press conference at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., to denounce Sinatra for using his power and influence to intimidate a writer before she’d written a word. They denounced his lawsuit and his assault on the First Amendment. As journalists, they understood what was at stake if Sinatra prevailed.

I retained the law firm of O’Melveny and Myers in Los Angeles and tried to keep working on the book, but was interrupted a few weeks later when I was in New York doing interviews and my lawyer called to tell me to get back to D.C. because the LA lawyers were coming to Washington for a meeting that would also be attended by my publisher. The LA lawyers said they’d received a tape recording from Sinatra’s lawyers of me supposedly misrepresenting myself as Sinatra’s authorized biographer, and this tape recording was the proof that they were going to present in court.

Now I was scared, even though I knew I hadn’t made such a telephone call. But I began to second-guess myself, wondering if maybe under the pressure I’d snapped my cap. By the time the lawyers arrived that Monday morning I was ready for handcuffs.

Three teams of lawyers sat down in my living room and put the tape in the recorder. No one said a word for the first two minutes because what we heard sounded like Porky Pig flying high on helium. In a squeaky voice, Porky said he was me and Frank Sinatra told me to call for an interview. The lawyers played that tape three times and we all listened to Porky Pig again and again before anyone said a word. Then all the lawyers laughed, clearly relieved, knowing the tape was a phony. I didn’t laugh.

“This lawsuit has gone on for almost a year and now someone is willing to lie under oath to say that I misrepresented myself to get an interview.”

“Don’t worry. We’ll send this to the tape labs at U.S.C., they’ll send the report to Sinatra’s team, and we’ll file for a dismissal. Meantime, just tape all your interviews.”

I tried to explain to the lawyers that you couldn’t always tape interviews, especially in the early 1980’s, when the technology wasn’t sophisticated. Taping in restaurants was difficult over the clinking of glasses, and taping phone interviews wasn’t legal in every state, even with two-party permission.

I finally decided that the best way to protect myself was to write a thank-you note to everyone I interviewed. That turned out to be 800 notes. They were polite and also protective. I’d thank them for the time they gave me in their home or their office or their favorite bar—wherever we’d done the interview; I’d compliment them on the polka dot bow tie they wore or the pretty pink blouse or their red tennis shoes; I’d mention the fabulous décor, or a particular piece of art, or our great salad in such-and-such a restaurant—any detail that set the time or place. Then I’d send it off and keep a copy in my files, because three or four years later when the book was finally published, they might very well have forgotten that interview or, more likely, wish they had.

That happened with Frank Sinatra Jr. He’d agreed to be interviewed when he was performing in Washington, D.C. His representative asked if I’d be bringing a camera crew, and I said no crew, just a still photographer. Then I quickly called my friend Stanley Tretick, one of President Kennedy’s favorite photographers who had worked for UPI and then LOOK magazine.

Stanley and I arrived at the Capitol Hill Hilton in the afternoon and went to Sinatra’s suite. His publicist met us and then disappeared when Frank Jr. entered the room. Sinatra’s only son sat down and asked me to sit close to him because he didn’t want to strain his voice. He was performing that night. So, I moved over, notebook in hand. The first 30 minutes of the interview went well as Sinatra Jr. talked about accompanying his father on tour and hanging out in Vegas with his father’s friends. Then he leaned over and said, “Hon, I know what happened to Jimmy Hoffa.”

I didn’t move. Because no one knew what happened to Jimmy Hoffa. They knew he was dead, but they didn’t know how or by whom. And now the son of a mob-connected man was going to tell me.

For a split second I wondered what I should wear when I got the Pulitzer Prize.

Just as Frank Sinatra Jr. leaned over to whisper in my ear, Stanley dropped his camera bags on the floor, and said, “Well out with it, man. What the hell happened to Hoffa?”

Frank Sinatra Jr. reared back as if he’d been clubbed. He looked at me, then he bolted from his chair and ran into the bedroom, slamming the door. His publicist came running out and said we had to leave. I begged for more time, saying the interview wasn’t finished, but the publicist was physically pushing us out the door.

Up to that point, Stanley Tretick had been one of my closest friends. Now I looked at him as if he’d just been possessed by the Tasmanian devil.

“Aw, hell. He doesn’t know what happened to Jimmy Hoffa.”

“Really?” I said. “And since when are photographers clairvoyant? And what kind of a lunkhead photographer throws a hissy in the middle of a reporter’s interview? Did it ever occur to you that what the son of a mob-connected man has to say about the disappearance of Jimmy Hoffa might be of interest?”

By now I was down the steps and storming the street to hail a cab. I refused to ride in the same car with a crazy person when I was homicidal. I didn’t speak to Stanley for some time, but he became my best pal again when the Sinatra biography was published. By then Frank Sinatra had dropped his lawsuit but his son now decided to sue, denying he’d ever given me an interview. His lawyers contacted my publisher and everyone braced for another lawsuit. But Stanley produced one of the photos he’d taken during our interview that showed me sitting next to Frank Sinatra Jr. with a notebook in [my] hand and a tape recorder on the table.

That photograph certainly trumped all of my little thank-you notes. Yet I can’t tell you how many times those notes saved me. When I wrote the Nancy Reagan biography, letters rained down on Simon & Schuster from corporate tycoons and all manner of political operatives, who took offense with the words attributed to them or to their wives or secretaries or associates, and at the bottom of every letter was a “cc” to President Ronald Reagan. Each time the publisher’s lawyer would call me to go over my notes and my tapes, and then he’d send a courteous reply, saying the publisher stands by the book and its accuracy.

At first, I wanted the publisher to “cc: President Reagan” just like all the letter writers had done, but the lawyer said no reason to stir the beast. “Those are weasel letters. They’re sent simply to show the flag.” He was right, and there were no retractions and no lawsuits.

That controversial biography became the cover of Time, Newsweek, People, Entertainment Weekly, and The Columbia Journalism Review, and [was] presented on the front pages of The New York Times, The New York Post, and the New York Daily News.

On the day of publication, President and Mrs. Reagan held a press conference to denounce the book, saying that I had—quote—“clearly exceeded the bounds of decency.” And three days later, President Richard Nixon agreed. President Nixon wrote a letter to President Reagan to commiserate. President Reagan responded, saying that everyone he knew had denied talking to the author. Reagan even named the minister of his church, who’d been cited as a source, and the minister had written a denial to all his parishioners in the Bel Air Presbyterian Church bulletin.

Now, I really tried not to respond to every accusation, but this one from a man of the cloth got to me, and I wrote to remind him of the 45 minute interview he’d given in his office. I enclosed a transcript of his taped remarks and asked him to please send around another church bulletin—with a correction. Of course, he didn’t, which proves the wisdom of Winston Churchill, who said that a lie flies halfway around the world before the truth gets its pants on.

Having rankled President Reagan and President Nixon, I later rattled President George Herbert Walker Bush. I’d written to him as a matter of courtesy, when I was under contract to Doubleday to write a historical retrospective of the Bush family, and said I’d appreciate an interview sometime at his convenience.

President Bush never responded to me but he directed his aide to write my publisher, saying:

“President Bush has asked me to say that he and his family are not going to cooperate with this book because the author wrote a book about Nancy Reagan that made Mrs. Reagan unhappy.” First Lady Barbara Bush had been so incensed when she saw my books displayed in the First Ladies Exhibit at the Smithsonian that she directed the curator to remove the display, which he did the next day. In fact, I might not have known about it had I not taken my niece to the Smithsonian a few weeks before and we’d seen the display and took a picture of it.

That photograph now hangs in my guest bathroom next to autographed cartoons from Jules Feiffer and Garry Trudeau. Over the years, that loo has become crowded with cartoons from all of my various books. My sister was very impressed when she saw them. She said to my husband, “I think it’s great that Kitty has put up all the bad ones.” My husband said, “There were no good ones.”

My biography on the Bush family dynasty was published in 2004, in the midst of a contentious presidential campaign. Bush Jr. was running for a second term, and I was lambasted by his White House press secretary, the White House deputy press secretary, the White House communications director, the Republican National Committee, and the house majority leader, Tom DeLay. Mr. DeLay even wrote a colorful letter to my publisher, saying that I was—quote—“in the advanced stage of a pathological career” and the publisher was in—quote—“moral collapse for publishing such a scandalous enterprise.”

When the Bush book became number one on the New York Times bestseller list, I was dropped from the masthead of The Washingtonian Magazine, where I’d been a contributing editor for 30 years. The new owner of the magazine was a Bush presidential appointee. The editor told me, “Your book was too personal. Too revealing.”

“But that’s what a biography is,” I said. “It’s an intimate examination of a person in his times, and in this case a powerful person in the public arena. The President of the United States influences our society, with actions that affect our lives.”

I quoted the actor Melvyn Douglas from the movie Hud. He talked about the mesmerizing power of a public image: “Little by little the look of the country changes because of the men we admire.” And Colum McCann, in his novel Let the Great World Spin, wrote: “Repeated lies become history, but they don’t necessarily become the truth.”

This is why biography is so vital to a healthy society. Whether authorized or unauthorized, biography presents a life story—sometimes it’s an x-ray of a manufactured image, sometimes it’s a gauzy bandage. The best biographers try to penetrate dross and drill for gold. As President Kennedy said, “The great enemy of the truth is very often not the lie—deliberate, contrived and dishonest—but the myth, persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic.”

I do not relish living in a world where information is authorized, sanitized, and homogenized. I read banned books. I applaud whistleblowers and I reject any suppression by church or state. To me, the unauthorized biography, which requires a combination of scholarly research and investigative reporting, is best directed at those figures still alive and able to defend themselves, who exercise power over our lives. . . . I firmly believe that unauthorized biography can be a public service and a boon to history.

The most solid support I’ve received over the years has come from writers—journalists and historians and biographers—who believe in the First Amendment. Who champion the public’s right to know.

These are principles that feed my soul and fill my heart, which is why I’m so grateful to be honored by you today with this award.

Thank you.

Kitty Kelley Wins 2023 BIO Award

Kitty Kelley has won the 14th BIO Award, bestowed annually by the Biographers International Organization to a distinguished colleague who has made major contributions to the advancement of the art and craft of biography.

Widely regarded as the foremost expert and author of unauthorized biography, Kelley has displayed courage and deftness in writing unvarnished accounts of some of the most powerful figures in politics, media, and popular culture. Of her art and craft, Kelley said, in American Scholar, “I do not relish living in a world where information is authorized, sanitized, and homogenized. I read banned books, I applaud whistleblowers, and I reject any suppression by church or state. To me, the unauthorized biography, which requires a combination of scholarly research and investigative reporting, is best directed at those figures still alive and able to defend themselves, who exercise power over our lives. . . . I firmly believe that unauthorized biography can be a public service and a boon to history.”

Among other awards, Kelley was the recipient of: the 2005 PEN Oakland/Gary Webb Anti-Censorship Award; the 2014 Founders’ Award for Career Achievement, given by the American Society of Journalists and Authors; and, in 2016, a Lifetime Achievement Award, given by The Washington Independent Review of Books. Her impressive list of lectures and presentations includes: leading a winning debate team in 1993, at the University of Oxford, under the premise “This House Believes That Men Are Still More Equal Than Women;” and, in 1998, a lecture at the Harvard Kennedy School for Government on the subject “Public Figures: Are Their Private Lives Fair Game for the Press?” In addition, Kelley was named by Vanity Fair to its Hall of Fame as part of the “Media Decade” and she has been a New York Times bestseller multiple times.

For over 30 years, Kelley has been a full-time freelance writer. In addition to the American Scholar, her writing has appeared in The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Newsweek, Ladies’ Home Journal, The Chicago Tribune, The Washington Times, The New Republic, and McCall’s. She is also a frequent contributor to The Washington Independent Review of Books.

Heather Clark, chair of the BIO Awards Committee, said: “The Awards committee is thrilled to recognize Kitty Kelley for her outstanding contributions to biography over nearly six decades. We admire her courage in speaking truth to power, and her determination to forge ahead with the story in the face of opposition from the powerful figures she holds accountable. The committee would also like to recognize Kitty’s many years of service to BIO, especially her fundraising prowess and commitment to growing BIO’s membership ranks. Kitty is a force of nature and a deeply inspiring figure who deserves the highest recognition from BIO for her contributions to advancing the art and craft of biography.”

Of her award, Kelley said, “I’m dazzled by the BIO honor and feel like Cinderella when the glass slipper fit. Please don’t wake me up from this dream.”

Previous BIO Award winners are Megan Marshall, David Levering Lewis, Hermione Lee, James McGrath Morris, Richard Holmes, Candice Millard, Claire Tomalin, Taylor Branch, Stacy Schiff, Ron Chernow, Arnold Rampersad, Robert Caro, and Jean Strouse.

Kelley will give the keynote address at the 2023 BIO Conference, on Saturday, May 20.

2023 BIO Award Winner Kitty Kelley interviewed by Heath Hardage Lee, March 28, 2023

David Bruce Smith’s Grateful American Book Award Honors Michelle Coles

by Kitty Kelley

No one hosts a more spectacular dinner party for a better cause than David Bruce Smith. His heavy parchment invitations of exquisite calligraphy arrive each fall to announce his Grateful American Foundation’s Book Award for the best children’s book of the year. The 2022 recipient was Michelle Coles for her first novel, Black Was the Ink. Coles joined previous winners, such as Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayer for her 2021 children’s book, The Beloved World of Sonia Sotomayer, and Child of the Dream: A Memoir of 1963 by Sharon Robinson, daughter of Jackie Robinson, the first African American to play in Major League Baseball.

The Grateful American Book Award comes with a check for $13,000, “a patriotic nod to the 13 original colonies,” says Smith — plus a lifetime pass to the New York Historical Society because, he says, “It’s hallowed objective is to celebrate knowledge,” and a medal, “designed by my mother, Clarice,” a noted artist who died a few months ago. Smith’s late father, Robert H. Smith, donated hundreds of millions to educational and cultural organizations throughout the Washington area, and his son and heir now continues his family’s philanthropy. David said his father, an immigrant’s son, “described himself as a ‘grateful American,’ which seemed a perfect name for my dream.”

“I started the Grateful American Foundation in 2014 because I heard an NPR report which indicated that Americans had a low level of historic literacy,” Smith said. “My friend, Bruce Cole, then Chairman of the National Endowment of the Humanities, suggested I create a book prize. So, with help and advice, I did just that. I selected 7th to 9th graders as my target because that age is probably one of the most difficult times for adolescents…. It’s my feeling that if a kid doesn’t want therapy, a book can — at least — be a paper psychiatrist.”

Smith, who’s dedicated to building youthful enthusiasm for American history, and co-authors a lively blog entitled “History Matters,” has written and published 13 books, many about his family, including his grandfather, Charles E. Smith, whose legacy remains the life communities he built during the 1960s in Washington and Maryland.

For this year’s celebration, Smith chose the Perry Belmont House, a magnificent Beaux Arts mansion, near Dupont Circle on New Hampshire Avenue NW, built in 1909. Guests were agog as they arrived. “Sublime, isn’t it,” said John Danielson, walking up the baroque marble steps and gesturing to the sculptured décor and channeled stonework. “A stunning home from a bygone era to celebrate David’s triumph in creating the Grateful American Book Prize.”

A man of immense charm, Danielson is chairman of the Education Advisory Council for the financial services firm of Alvarez and Marsal. He lives in Georgetown and seems to know everyone in the city, as he graciously introduces Douglas Bradburn, CEO of Mount Vernon and his wife, Nadene; Matthew Hiktzik, producer of the 2004 Holocaust documentary film, Paper Clips; Mindy Berry, Senior Executive at the National Endowment for the Humanities; Teddi Marshall, C-suite business executive; Doreen Cole, whose late husband was the longest serving chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities; writer Michael Bishop; Neme Alperstein, teacher with the NYC Dept. of Education; Courtney Chapin, Executive Director of Ken Burns’s Better Angels Society; Scott Stephenson, director of the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia, Elizabeth Robelen, long-time editor for the Washington Independent Review of Books and her husband, Carter Reardon, instructor with the Dog Tag Fellowship Program for veterans at Georgetown University.

“Helping those who bring history to young people is an important purpose of this evening,” said David O. Stewart, who’s written several prize-winning books, including George Washington: The Political Rise of America’s Founding Father.

Knight A. Kiplinger opened the award presentation by introducing himself as a history nerd. “I come from a long line of history nerds,” said the publishing mogul. “My late father, Austin Kiplinger, and I (both of us journalists, too) have been passionate supporters of local history.” The results of that family passion — the Kiplinger Collection and the Kiplinger Research Library — now reside in the renovated Carnegie Library on Mt. Vernon Square, which has morphed into the D.C. History Center.

All history nerds and grateful Americans gave the evening rounds of rousing applause.

Originally published in The Georgetowner, November 9, 2022

A Trail of Tears and Triumph

by Kitty Kelley

“April is the cruelest month,” wrote the poet T.S. Eliot, and for followers of Martin Luther King Jr., April 4, 1968, was the cruelest day. At 6:01 p.m. on that Thursday, the beloved preacher of nonviolence was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee.

“April is the cruelest month,” wrote the poet T.S. Eliot, and for followers of Martin Luther King Jr., April 4, 1968, was the cruelest day. At 6:01 p.m. on that Thursday, the beloved preacher of nonviolence was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee.

Hours later, riots erupted throughout the country as angry mobs smashed windows, trashed stores, and blew up cars, leaving dozens dead and more than 100 cities smoldering. President Lyndon Johnson finally summoned the National Guard to restore order.

More than five decades later, some scars remain, but Dr. King’s dream of a beloved community still shines, even in the poorest pockets of the country. I recently joined Stanford University’s “Following King: Atlanta to Memphis” tour, led by Professor Clayborne Carson, senior editor of The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Vols. I-VII. Traveling by bus for a week — masked, in the era of covid — we patronized only minority-owned hotels and restaurants.

We began in Atlanta with a visit to Dr. King’s last home, the one he purchased after winning the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize. We toured the National Center for Civil and Human Rights and learned from a freshman at Morehouse College why he values his education on the 61-acre campus of one of America’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU), which is close to Spelman College, an HBCU for women:

“We both fall under the umbrella of Atlanta University Center, so we can attend classes on either campus…Our slogan here at Morehouse is ‘Let There be Light,’ and while it’s prevalent in my generation [Class of 2025] not to speak your mind lest you be canceled, here, people are not making fun of you or out to cancel you. They tell us: ‘Say your ignorance in class so you don’t say it in the world.’”

Before leaving Atlanta, we visit the Ebenezer Baptist Church, the spiritual home of Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, where the Rev. Raphael G. Warnock now serves every Sunday as pastor. The rest of the week, he serves as Georgia’s junior senator in the U.S. Senate.

Boarding the bus, we headed for Montgomery, Alabama, home of the Confederacy, where we visit the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, created by Bryan Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), the nonprofit that guarantees the defense of any prisoner in Alabama sentenced to death. For many of us, this is the most upsetting museum on the tour because it forces you to see the terrible connection between 1865 and today.

The EJI has identified more than 4,000 Black men, women, and children who were lynched. At the site’s center hang 800 rusted steel monuments, one for each county in the U.S. where documented lynchings took place. Entering the museum, we were confronted with replicas of slave pens, where we saw and heard first-person accounts from enslaved people describing what it was like to be ripped from their families and await sale at the nearby auction block. We learned what “sold down the river” means: Many enslaved people were punished with a transfer from the North to harsher conditions in the South. Etched in bronze is Harriet Tubman’s quote, “Slavery is the next thing to hell.”

On a nearby street corner, we meet the artist Michelle Browder, who showed us her outdoor gallery honoring “Mothers of Gynecology”; her 15-foot-high sculptures depict three enslaved women subjected to brutal experiments for “supposed” medical advancement.

From Montgomery, we were bused to Birmingham (aka “Bombingham”) and the 16th Street Baptist Church, where four little girls were killed by a bomb as they prepared to sing in their choir on September 15, 1963. The pastor’s undelivered sermon that Sunday was entitled “A Love that Forgives.”

Weeks before, 300,000 people had gathered peacefully on the National Mall in Washington, DC, to hear Dr. King’s soaring “I Have a Dream” speech. Later, he was jailed in Alabama. While there, he wrote his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail” on scraps of paper and bits of toilet tissue that his lawyer smuggled out piece by piece on each visit. Dr. King’s message berated white moderates “devoted to order, not to justice,” particularly those white church leaders “more cautious than courageous.”

From Montgomery, we traveled to Selma to meet our no-nonsense guide in the projects. “We’re in the ‘hood now, so if you hear a pop-pop, duck,” she said. People on the bus squirmed as she delivered her blunt commentary:

“Selma is a city of barely 20,000, and 80 percent of us are African American, still living in the poorest wards…Voting registration has shrunk because folks ask, ‘What’s voting done for us?’ We’re a broken economy, a broken community…Hate groups study us as a failed model of Democratic policies.”

Rain fell as we walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, named for a Confederate general and Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan and the site of “Bloody Sunday,” March 7, 1965, when police attacked Civil Rights marchers with horses, clubs, and tear gas.

We later stopped in Meridian and Jackson, Mississippi, enroute to Memphis, where we visited the Lorraine Motel, with its white plastic wreath of blood red roses marking the spot on the second-floor balcony where Dr. King was assassinated. The plaque beneath reads:

“They said one to another,

Behold, here cometh the dreamer,

Let us slay him

And we shall see what will become of his dream.”

– Genesis 37.19-20

The motel site has been expanded into a complex of buildings incorporated as the National Civil Rights Museum in 1991, the first in the U.S. dedicated to telling the Black Civil Rights story. It’s also been called “The Conspiracy Museum” because its second floor, entitled “Lingering Questions,” chronicles the capture and arrest of James Earl Ray and explores myriad conjectures about whether Dr. King’s killer acted alone.

Outside on the street, a tiny woman named Jacqueline Smith protests the $27 million museum complex. She weighs no more than 90 pounds, but her outrage is ferocious. She’s been standing on the corner every day since 1988, when she was evicted from the motel to make way for the museum’s construction.

“What’s the point of all this?” she asks. “What does this rich museum offer the needy, the homeless, the poor, the hungry, the displaced, and the disadvantaged? Dr. King said: ‘Spend the necessary money to get rid of slums, eradicate poverty.’ This museum was built with non-unionized labor. Dr. King was all for unionized workers. This museum celebrates his murderer… does the John F. Kennedy Library celebrate Lee Harvey Oswald?”

Someone starts to speak, but Jackie brooks no interruption. “Why don’t you white people do what’s right for a change?”

Quietly, we return to our bus, edified by Dr. King’s vocal disciple.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Queen of the Unauthorized Biography Spills Her Own Secrets

By Seth Abramovitch

There was, not that long ago, a name whose mere invocation could strike terror in the hearts of the most powerful figures in politics and entertainment.

That name was Kitty Kelley.

If it’s unfamiliar to you, ask your mother, who likely is in possession of one or more of Kelley’s best-selling biographies — exhaustive tomes that peer unflinchingly (and, many have claimed, nonfactually) into the personal lives of the most famous people on the planet.

“I’m afraid I’ve earned it,” sighs Kelley, 79, of her reputation as the undisputed Queen of the Unauthorized Biography. “And I wave the banner. I do. ‘Unauthorized’ does not mean untrue. It just means I went ahead without your permission.”

That she did. Jackie Onassis, Frank Sinatra, Nancy Reagan — the more sacred the cow, the more eager Kelley was to lead them to slaughter. In doing so, she amassed a list of enemies that would make a despot blush. As Milton Berle once cracked at a Friars Club roast, “Kitty Kelley wanted to be here tonight, but an hour ago she tried to start her car.”

Only a handful of contemporary authors have achieved the kind of brand recognition that Kelley has. At the height of her powers in the early 1990s, mentions of the ruthless journo with the cutesy name would pop up everywhere from late night monologues to the funny pages. (Fully capable of laughing at herself, her bathroom walls are covered in framed cartoons drawn at her expense.)

Kelley is hard to miss around Washington, D.C. She drives a fire-engine red Mercedes with vanity plates that read “MEOW.” The car was a gift from former Simon & Schuster chief Dick Snyder, who was determined to land Kelley’s Nancy Reagan biography.

“Simon & Schuster said, ‘Kitty, Dick really wants the book. What will it take to prove that?’ ” she recalls. “I said,  ‘A 560 SL Mercedes, bright red, Palomino interior.’ ‘We’ll be back to you.’ ” She insists she was only kidding. But a few days later, Kelley answered the phone and was directed to walk to the nearest corner: “Your bright red 560 SL is sitting there waiting for you.” Sure enough, there it was. The “MEOW” plates were a surprise gift from the boyfriend who would become her second husband, Dr. John Zucker.

‘A 560 SL Mercedes, bright red, Palomino interior.’ ‘We’ll be back to you.’ ” She insists she was only kidding. But a few days later, Kelley answered the phone and was directed to walk to the nearest corner: “Your bright red 560 SL is sitting there waiting for you.” Sure enough, there it was. The “MEOW” plates were a surprise gift from the boyfriend who would become her second husband, Dr. John Zucker.

Ask Kelley how many books she has sold, and she claims not to know the exact number. It is many, many millions. Her biggest sellers — 1986’s His Way, about Frank Sinatra, and 1991’s Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography, began with printings of a million each, which promptly sold out. “But they’ve gone to 12th printings, 14th printings,” she says. “I really couldn’t tell you how many I’ve sold in total.” She does recall first breaking into The New York Times‘ best-seller charts, with 1978’s Jackie Oh! “I remember the thrill of it. I remember how happy I was. It’s like being prom queen,” she says. “Which I actually was about 100 years ago.”

Regardless of one’s opinions about Kelley, or her methodology, there can be no denying that her brand of take-no-prisoners celebrity journalism — the kind that in 2022 bubbles up constantly in social media feeds in the form of TMZ headlines and gossipy tweets — was very much ahead of its time.

In fact, a detail from Kelley’s 1991 Nancy Reagan biography trended in December when Abby Shapiro, sister of conservative commentator Ben Shapiro, tweeted side-by-side photos of Madonna and the former first lady. “This is Madonna at 63. This is Nancy Reagan at 64. Trashy living vs. Classic living. Which version of yourself do you want to be?” read the caption. Someone replied with an excerpt from Kelley’s biography that described Reagan as being “renowned in Hollywood for performing oral sex” and “very popular on the MGM lot.” The excerpt went viral and launched a wave of memes. “It doesn’t fit with the public image. Does it? It just doesn’t. And the source on that was Peter Lawford,” says Kelley, clearly tickled that the detail had resurfaced.

While amplifying those kinds of rumors might not suggest it, in many eyes, Kelley is something of a glass-ceiling shatterer. “Back when she started in the 1970s, it was a largely male profession,” says Diane Kiesel, a friend of Kelley’s who is a judge on the New York Supreme Court. “She was a trailblazer. There weren’t women writing the kind of hard-hitting books she was writing. I’m sure most of her sources were men.”

But what of her methodology? Kelley insists she never sets out to write unauthorized biographies. Since Jackie Oh!, she has always begun her research by asking her subjects to participate, often multiple times. She is invariably turned down, then continues about the task anyway. She’s also known to lean toward blind sourcing and rely on notes, plus tapes and photographs, to back up the hundreds of interviews that go into every book.

“Recorders are so small today, but back then it was very hard to carry a clunky tape recorder around and slap it on the table in a restaurant and not have all of that ambient noise,” she says. To prove the conversations happened, Kelley devised a system in which she would type up a thank-you note containing the key details of their meeting — location, date and time — and mail it to every subject, keeping a copy for herself. If a subject ever denied having met with her, she would produce the notes from their conversation and her copy of the thank-you note.

So far, the system has worked. While many have tried to take her down, the ever-grinning Kelley has never been successfully sued by a source or subject.

Now 79, she lives in the same Georgetown townhouse she purchased with her $1.5 million advance (that’s $4 million adjusted for inflation) for His Way, which the crooner unsuccessfully sued to prevent from even being written.

Among the skeletons dug up by Kelley in that 600-page opus: that Ol’ Blue Eyes’ mother was known around  Hoboken, New Jersey, as “Hatpin Dolly” for a profitable side hustle performing illegal abortions. Sinatra’s daughter Nancy Sinatra said the family “strangled on our pain and anger” over the book’s release, while her sister, Tina, said it caused her father so much stress, it forced him to undergo a seven-and-a-half-hour surgical procedure on his colon.

Hoboken, New Jersey, as “Hatpin Dolly” for a profitable side hustle performing illegal abortions. Sinatra’s daughter Nancy Sinatra said the family “strangled on our pain and anger” over the book’s release, while her sister, Tina, said it caused her father so much stress, it forced him to undergo a seven-and-a-half-hour surgical procedure on his colon.

Giggly, vivacious and 5-foot-3, Kelley presents more like a kindly neighbor bearing blueberry muffins than the most infamous poison-pen author of the 20th century. “I seem to be doing more book reviewing than book writing these days,” she says in one of our first correspondences and points me to a review of a John Lewis biography published in the Washington Independent Review of Books.

She has not tackled a major work since 2010’s Oprah — a biography of Oprah Winfrey touted ahead of its release by The New Yorker as “one of those King Kong vs. Godzilla events in celebrity culture” but which fizzled in the marketplace, barely moving 300,000 copies. Among its allegations: that Winfrey had an affair early in her career with John Tesh — of Entertainment Tonight fame — and that, according to a cousin, the talk show host exaggerated tales of childhood poverty because “the truth is boring.”

“We had a falling out because I didn’t want to publish the Oprah book,” says Stephen Rubin, a consulting publisher at Simon & Schuster who grew close to Kelley while working with her at Doubleday on 2004’s The Family: The Real Story of the Bush Dynasty.

“I told her that audience doesn’t want to read a negative book about Saint Oprah. I don’t think it’s something she should have even undertaken. We have chosen to disagree about that.”

The book ended up at Crown. It would be nine months before Kelley would speak to Rubin again. They’ve since reconciled. “She’s no fun when she’s pissed,” Rubin notes.

Adds Kelley of Winfrey’s reaction to the book: “She wasn’t happy with it. Nobody’s happy with [an unauthorized] biography. She was especially outraged about her father’s interview.” She is referencing a conversation she had, on the record, with Winfrey’s father, Vernon Winfrey, in which he confirmed the birth of her son, who arrived prematurely and died shortly after birth.

But Kelley says the backlash to Oprah: A Biography and the book’s underwhelming sales had nothing to do with why she hasn’t undertaken a biography since. Rather, her husband, a famed allergist in the D.C. area who’d give a daily pollen report on television and radio, died suddenly in 2011 of a heart attack. “John was the great love of her life,” says Rubin. “He was an irresistible guy — smart, good-looking, funny and mad for Kitty.”

“Boy, I was knocked on my heels,” she says of Zucker’s death. “He hated the cold weather. He insisted we go out to the California desert. We were in the desert, and he died at the pool suddenly. I can’t account for a couple of years after that. It was a body blow. I just haven’t tackled another biography since.”

A decade having passed, Kelley does not rule out writing another one — she just hasn’t yet found a subject worthy of her time. “I can’t think of anyone right now who I would give three or four years of my life to,” Kelley says. “It’s like a college education.”

For fun, I throw out a name: Donald Trump. Kelley shakes her head vigorously. “I started each book with real respect for each of my subjects,” she says. “And not just for who they were but for what they had accomplished and the imprint that they had left on society. I can’t say the same thing about Donald Trump. I would not want to wrap myself in a negative project for four years.”

“You know,” I interrupt, “I’m imagining people reading that quote and saying, ‘Well, you took ostensibly positive topics and turned them into negative topics.’ How would you respond to that?”

“I would say you’re wrong,” Kelley replies. “That’s what I would say. I think if you pick up, I don’t know — the Frank Sinatra book, Jackie Oh!, the Bush book — yes, you’re going to see the negatives and the positives, which we all have. But I think you’ll come out liking them. I mean, we don’t expect perfection in the people around us, but we seem to demand it in our stars. And yet, they’re hardly paragons. Each book that I’ve written was a challenge. But I would think that if you read the book, you’re going to come out — no matter what they say about the author — you’re going to come out liking the subject.”

***

Kelley arrived in the nation’s capital in 1964. She was 22 and, through the connections of her dad, a powerful attorney from Spokane, Washington, she landed an assistant job in Democratic Sen. Eugene McCarthy’s office. She worked there for four years, culminating in McCarthy’s 1968 presidential bid. It was a tumultuous time. McCarthy’s Democratic rival, Robert F. Kennedy, was gunned down in Los Angeles at a California primary victory party on June 5. When Hubert Humphrey clinched the nomination that August amid the DNC riots in Chicago, Kelley’s dreams of a future in a McCarthy White House were dashed, and she decided a life in politics was not for her.

“But I remain political,” Kelley clarifies. “I am committed to politics and have been ever since I worked for Gene McCarthy. I was against the war in Vietnam. I don’t come from that world. I come from a rich, right-wing Republican family. My siblings avoid talking politics with me.”

In 1970, she applied for a researcher opening in the op-ed section at The Washington Post. “It was a wonderful job,” she recalls. “I’d go into editorial page conferences. And whatever the writers would be writing, I would try and get research for them. Ben Bradlee’s office was right next to the editorial page offices. And if he had both doors open, I would walk across his office. He was always yelling at me for doing it.”

According to her own unauthorized biography — 1991’s Poison Pen, by George Carpozi Jr. — Kelley was fired for taking too many notes in those meetings, raising red flags for Bradlee, who suspected she might be researching a book about the paper’s publisher, Katharine Graham. Kelley says the story is not true.

“I have not heard that theory, but I will tell you I loved Katharine Graham, and when I left the Post, she gave me a gift. She dressed beautifully, and when the style went from mini to maxi skirts —because she was tall and I am not, I remember saying, ‘Mrs. Graham, you’re going to have to go to maxis now. And who’s going to get your minis?’ She laughed. It was very impudent. But then I was handed a great big box with four fabulous outfits in them — her miniskirts.”

Kelley says she left the Post after two years to pursue writing books and freelancing. She scored one of the bigger scoops of 1974 when the youngest member of the upper house — newly elected Democratic Sen. Joe Biden of Delaware, then 31 — agreed to be profiled for Washingtonian, a new Beltway magazine.

Biden was still very much in mourning for his wife and young daughter, killed by a hay truck while on their way to buy a Christmas tree in Delaware on Dec. 18, 1972. The future president’s two young sons, Beau and Hunter, survived the wreck; Biden was sworn into the Senate at their hospital bedsides.

After the accident, Biden developed an almost antagonistic relationship to the press. But his team eventually softened him to the idea of speaking to the media. That was precisely when Kelley made her ask.

Biden would come to deeply regret the decision. The piece, “Death and the All-American Boy,” published on June 1, 1974, was a mix of flattery (Kelley writes that Biden “reeks of decency” and “looks like Robert Redford’s Great Gatsby”), controversy (she references a joke told by Biden with “an antisemitic punchline”) and, at least in Biden’s eyes, more than a little bad taste.

The piece opens: “Joseph Robinette Biden, the 31-year-old Democrat from Delaware, is the youngest man in the Senate, which makes him a celebrity of sorts. But there’s something else that makes him good copy: Shortly after his election in November 1972 his wife Neilia and infant daughter were killed in a car accident.”

Later, Kelley writes, “His Senate suite looks like a shrine. A large photograph of Neilia’s tombstone hangs in the inner office; her pictures cover every wall. A framed copy of Milton’s sonnet ‘On His Deceased Wife’ stands next to a print of Byron’s ‘She Walks in Beauty.’ “

But it was one of Biden’s own quotes that most incensed the future president.

She writes: ” ‘Let me show you my favorite picture of her,’ he says, holding up a snapshot of Neilia in a bikini. ‘She had the best body of any woman I ever saw. She looks better than a Playboy bunny, doesn’t she?’ “

“I stand by everything in the piece,” says Kelley. “I’m sorry he was so upset. And it’s ironic, too, because I’m one of his biggest supporters. It was 48 years ago. I would hope we’ve both grown. Maybe he expected me to edit out [the line about the bikini], but it was not off the record.” Still, she admits her editor, Jack Limpert, went too far with the headline: “I had nothing to do with that. I was stunned by the headline. ‘Death and the All-American Boy.’ Seriously?”

It would be 15 years before Biden gave another interview, this time to the Washington Post‘s Lois Romano during his first presidential bid, in 1987. Biden, by then remarried to Jill Biden, recalled to Romano, “[Kelley] sat there and cried at my desk. I found myself consoling her, saying, ‘Don’t worry. It’s OK. I’m doing fine.’ I was such a sucker.”

Kelley’s first book wasn’t a biography at all. “It was a book on fat farms,” she says, which was based on a popular article she’d written for Washington Star News on San Diego’s Golden Door — one of the country’s first luxury spas catering to celebrity clientele like Natalie Wood, Elizabeth Taylor and Zsa Zsa Gabor.

“On about the third day, the chef came out, and he said, ‘Would you like a little something?’ ” says Kelley. “He was Italian. I said, ‘Yes, I’m so hungry.’ And he kind of laughed. Turns out he wasn’t talking about tuna fish. I said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me.’ He said, ‘I have sex all the time with the people here.’ I said, ‘I should tell you, I’m here writing a book.’ He said, ‘I’ll tell you everything!’ I warned him, ‘OK — but I’m going to use names.’ And I did.”

The book, a 1975 paperback called The Glamour Spas, sold “14 copies, all of them bought by my mother,” she says. But the publisher, Lyle Stuart, dubbed in a 1969 New York Times profile as the “bad boy of publishing,” was impressed enough with Kelley’s writing that he hired her in 1976 to write a biography of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

The crown jewel of the book that would become Jackie Oh! was Kelley’s interview with Sen. George Smathers, a Florida Democrat and John F. Kennedy’s confidant. (After they entered Congress the same year and quickly became close friends, Kennedy asked Smathers to deliver two significant speeches: at his 1953 wedding and his 1960 DNC nomination.)

“It was quite explosive,” Kelley recalls of her three-hour dinner with Smathers. “He was very charming, very Southern and funny. And he said, ‘Oh, Jack, he just loved women.’ And he went on talking, and he said, ‘He’d get on top of them, just like a rooster with a hen.’ I said, ‘Senator, I’m sorry, but how would you know that unless you were in the room?’ He said, ‘Well, of course I was in the room. Jack loved doing it in front of people.’

“The senator, to his everlasting credit, did not deny it,” Kelley continues. “A reporter asked him, ‘Did you really say those things?’ And the senator replied, ‘Yeah, I did. I think I was just run over by a dumb-looking blonde.’ “

She followed that one, which landed on the New York Times best-seller list, with 1981’s Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star, which underwhelmed. Her next two, however — His Way and Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography (for which she earned a $3.5 million advance, $9 million in 2022 adjusted for inflation) — were best-sellers, moving more than 1 million copies each in hardcover.

She followed that one, which landed on the New York Times best-seller list, with 1981’s Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star, which underwhelmed. Her next two, however — His Way and Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography (for which she earned a $3.5 million advance, $9 million in 2022 adjusted for inflation) — were best-sellers, moving more than 1 million copies each in hardcover.

Her 1997 royal family exposé, The Royals — which presaged The Crown, the Lady Di renaissance and Megxit mania by several decades — contained allegations that the British royal family had obfuscated their German ancestry.

“Sinatra was huge and Nancy was huge, but The Royals gave me more foreign sales than I’ve ever had on any book,” Kelley beams, adding that the recent headlines about Prince Andrew settling with a woman who accused him of raping her as a teenager at Jeffrey Epstein’s compound “really shows the rotten underbelly of the monarchy, in that someone would be so indulged, really ruined as a person, without much purpose in life.”

“Looking around,” I ask Kelley, “is society in decline?”

“What a question,” she replies. “Let’s say it’s being stressed on all sides. I think it’s become hard to find people that we can look up to — those you can turn to to find your better self. We used to do that with movie stars. People do it with monarchy. Unfortunately, there are people like Kitty Kelley around who will take us behind the curtain.”

Contrary to her public persona, Kelley is known in D.C. social circles for her gentility. Judge Kiesel, a part-time author, first met her eight years ago when Kelley hosted a reception for members of the Biographers International Organization at her home.

“What amazed me was she was such the epitome of Southern hospitality, even though she isn’t from the South,” says Kiesel. “I remember her standing on the front porch of her beautiful home in Georgetown and personally greeting every member of this group who had showed up. There had to be close to 200 of us.”

Kelley hosts regular dinner parties of six to 10 people. “She likes to mix people from publishing, politics and the law,” says Kiesel. When Kiesel, who lives in New York City, needed to spend more time in D.C. caring for a sister diagnosed with cancer, Kelley insisted she stay at her home. “She threw a little dinner party in my honor,” Kiesel recalls. “I said, ‘Kitty — why are you doing this?’ She said, ‘You’re going to have a really rough couple of months and I wanted to show you that I’m going to be there for you.’ People look at her as this tough-as-nails, no-holds-barred writer — but she’s a very kind, sweet, generous woman.”

For Kelley, life has grown pretty quiet the past few years: “It’s such a solitary life as a writer. The pandemic has turned life into a monastery.” Asked whether she dates, she lets out a high-pitched chortle. “Yes,” she says. “When asked. No one serious right now. Hope springs eternal!”

I ask her if there is anything she’s written she wishes she could take back. “Do I stand by everything I wrote? Yes. I do. Because I’ve been lawyered to the gills. I’ve had to produce tapes, letters, photographs,” she says, then adds, “But I do regret it if it really brought pain.”

Says Rubin: “People think she’s a bottom-feeder kind of writer, and that’s totally wrong. She’s a scrupulous journalist who writes no-holds-barred books. They’re brilliantly reported.”

Before I bid her adieu, I can’t resist throwing out one more potential subject for a future Kelley page-turner.

“What about Jeff Bezos?” I say.

She pauses to consider, and you can practically hear the gears revving up again.

“I think he’s quite admirable,” she says. “First of all, he saved The Washington Post. God love him for that. And he took on someone who threatened to blackmail him. He stood up to it. I think there’s much to admire and respect in Jeff Bezos. He sounds like he comes from the most supportive parents in the world. You don’t always find that with people who are so successful.”

“So,” I say. “You think you have another one in you?”

“I hope so,” Kelley says. “I know you’re going to end this article by saying … ‘Look out!’ “

This story first appeared in the March 2 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine.

https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/lifestyle/arts/kitty-kelley-interview-unauthorized-biographies-1235101933/

Photo credits: top of page, Amy Lombard; Kitty Kelley in Merc, Amy Lombard; Kitty Kelly with His Way, Bettmann/Getty Images; Kitty Kelley with Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star, Harry Hamburg/NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images

Dishing With Kitty

by Judith Beerman

Originally published by The Georgetown Dish December 13, 2021

Internationally acclaimed writer and long-time Georgetown resident, Kitty Kelley is renowned for her bestselling biographies of the most influential and powerful personalities of the last 50 years.

Having captivated my friends with her insights into Frank Sinatra, Oprah and the Kennedys, the always charming and witty author graciously dishes with us!

1. Favorite spot in Georgetown?

The gardens and grounds of Dumbarton Oaks.

2. What place to visit next?

I dream about returning to Provence.

3. What’s last book you read that you recommend?

Not last book read but two of recent best: A Gentleman of Moscow by Amor Towles and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

4. What or who is greatest inspiration?

Those who reach outside themselves to help others like First Responders, Doctors Without Borders, MADD (Mothers Against Drunk Drivers), et. al.

5. Whom would you invite to next dinner party?

Dr. Fauci—to thank him.

6. What did you discover re: self during pandemic?

I look better masked!!

7. Spirit animal?

A cat, of course.