Kitty Kelley and Sy Hersh

Photo 9/4/21

First Friends

by Kitty Kelley

Imagine you are a contestant on “Jeopardy!” and you select “Presidents and Their Female Friends” for $200. The host says: “This 20th-century president was known for his close relationships with women.” You hit the buzzer and choose either John F. Kennedy or Bill Clinton, both of whom had well-documented extra-marital affairs.

Imagine you are a contestant on “Jeopardy!” and you select “Presidents and Their Female Friends” for $200. The host says: “This 20th-century president was known for his close relationships with women.” You hit the buzzer and choose either John F. Kennedy or Bill Clinton, both of whom had well-documented extra-marital affairs.

Unfortunately, you don’t make it to Final Jeopardy because the correct answer, according to Gary Ginsberg’s First Friends, is, “Who is Franklin Delano Roosevelt?”

In Ginsberg’s enchanting hybrid work of history and biography, he describes FDR’s enduring relationship with Margaret “Daisy” Suckley in delightful detail as the person FDR held “closer to his heart than anyone.” Although Ginsberg doubts an affair between the distant cousins, he cites Roosevelt as the only president to have had a woman as his best friend.

Previously, readers have been treated to books on first families, first ladies, first butlers, first chefs, first photographers, first dogs, and first cats. For his first book, Ginsberg, who served in the Clinton Administration, ingeniously presents bite-size biographies of U.S. presidents and their best friends — and how those friendships influenced presidential legacies and affected the country.

The author wraps history and humanity in a sparkling package, concentrating on nine U.S. chief executives and their closest friends, from Thomas Jefferson and James Madison through Bill Clinton and Vernon Jordan. It’s an inspired idea that will thrill anyone who loves life stories woven into presidential history.

Given the current age of tweets and texts, plus the nation’s diminished attention span, Ginsberg has devised a unique way to engage readers, fashioning 18 lives within 359 pages of narrative and perhaps sweeping into the dustbin the turgid 1,000-plus-page tomes of such as Robert Caro, who’s written four volumes to date on Lyndon Baines Johnson, with one more hulking in the wings.

If Mies van der Rohe was right, then less is more, and brevity is to be celebrated, as is exemplified by:

The 23rd Psalm (118 words)

The Magna Carta (650 words)

Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address (272 words)

The Great Emancipator’s friendship with Joshua Speed, who became a slave owner years after meeting Lincoln, is included in Ginsberg’s book and illustrates the bond between two men whose differing principles put a decade’s worth of distance between them before they mended their breach.

Probably the most bizarre first friendship in the book is the one shared by Richard Nixon and Charles “Bebe” Rebozo, a Cuban exile who got branded as Nixon’s bagman during the Watergate scandal. Pat Nixon called Rebozo “Dick’s sponge.” In 42 years, the two men never talked politics but shared long silences together, drinking copious amounts of alcohol.

By far the strongest chapter in Ginsberg’s book — and the chronicle of a relationship that changed history — was Harry Truman’s friendship with Eddie Jacobson, the son of a Jewish shoemaker and Truman’s former business partner in Missouri. It was Jacobson who prevailed on the president in 1948 to go against revered Secretary of State George Marshall and recognize the new state of Israel as the Jewish homeland.

Since, according to the Bard, “Brevity is the soul of wit and tediousness the limbs and outward flourishes,” I will be brief in my conclusion: Gary Ginsberg has written in First Friends a romp of a read. Enjoy!

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Blind Man’s Bluff

by Kitty Kelley

Some memoirs flicker like fireflies on a summer night. Others pierce your psyche with their subjects’ tortured experiences, consequent miseries, and — finally — their oh-so-glorious survival. The Story of My Life by Helen Keller, Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt, The Liars’ Club by Mary Karr, Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou are among the memoirs that leave you breathless; they’re books you keep and don’t pawn off on your neighbor’s yard sale.

Some memoirs flicker like fireflies on a summer night. Others pierce your psyche with their subjects’ tortured experiences, consequent miseries, and — finally — their oh-so-glorious survival. The Story of My Life by Helen Keller, Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt, The Liars’ Club by Mary Karr, Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou are among the memoirs that leave you breathless; they’re books you keep and don’t pawn off on your neighbor’s yard sale.

Now comes another keeper: Blind Man’s Bluff by James Tate Hill. With his pluperfect title, Hill winningly recounts his life after he was declared legally blind. “I was ready for a change, ready to be changed, but the loss of my sight that month before turning sixteen wasn’t what I had in mind,” he writes.

After being diagnosed with Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, a genetic condition that causes gradual blindness mostly in men, Hill burrows into denial and bluffs his way through blindness until his mid-30s. Armed with a basketful of euphemisms for his affliction — “sightlessness,” “print disabled,” “limited seeing,” “bad eyes,” “blurred vision” — he forges ahead, psychologically unable to accept a world of white canes and seeing-eye dogs.

He refuses to admit to himself, his teachers, his friends, and even his first wife that he is blind. “Not speaking of it, not reminding others of it, not letting it hang like a banner above my head let me almost forget, and to almost forget was to make it almost untrue.”

Some days in school, he lets himself be docked for absence rather than risk signing his name over another student’s on the attendance sheet. In classes, he pretends to take notes, scrawling pages of gibberish that he later throws away. Poignantly, he lines the shelves in his apartment with books he can’t read while hiding his Talking Books under the bed:

“I was aware of the stigma associated with books on tape. Jokes on sitcoms implied audiobooks were to physical books what flag football is to the NFL.”

Reading this memoir makes you realize how much you take sight for granted. Just being passed a plate of food can be fraught for a blind person. “So many things can go wrong,” Hill explains, “not limited to my thumb and forefinger landing in the wrong section of the plate; touching, defacing or possibly knocking onto the floor a brownie or precariously arranged cheese on a cracker, or, the Grand Guignol of canapes, a chip that must be sent on a recon mission into a dip of unknown depth or viscosity.”

Crossing the street becomes a potential dance with death:

“In daylight, you can’t rely on headlights and traffic lights to know when it’s safe…Sometimes other pedestrians are waiting on the curb, and you can cross behind them…At night when there are no pedestrians to whom you can pin your safety and no traffic lights or stop signs to part traffic, you can listen for cars.”

One day, Hill nearly loses his life when he changes his route and crosses on what he thinks is a green light, and then “a car horn punches a hole in the morning,” as he stumbles to a concrete island, escaping “almost death.”

Hill’s story is funny and sad at the same time, and raw in its honesty as he recounts the rejection by his first wife, who initiates divorce proceedings after six years of marriage. Both had cultivated facades: His was having vision; hers was having an outgoing personality. Alone with him, she clams up and resents his dependence as much as he hates being dependent. Despite having earned three master’s degrees, he cannot earn a living as a writer, and only barely as a teacher, forcing her to become the primary breadwinner.

“I wished I were a man capable of leaving a bad relationship,” he recalls, “but I barely found the courage to leave the apartment.”

After his second novel is rejected, Hill identifies with Paul Giamatti’s character — a divorced, unpublished novelist — in the film “Sideways.” But then Hill rallies, reactivates his online-dating account, and somersaults into a relationship that finally makes him feel secure enough to stop bluffing. Once he drops his pretense and admits his disability, he finds happily-ever-after endings as a person, a teacher, and a husband.

In the book’s last chapter, entitled “Basketball,” Hill and his new wife are in a gym playing hoops. They chase down rebounds and launch wild jumpers and crooked free throws, laughing as they miss nearly every shot.

“Every once in a while a three-pointer rattles in, and we scream our heads off,” Hill writes, “champions after a last-second shot.”

Champions, indeed.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

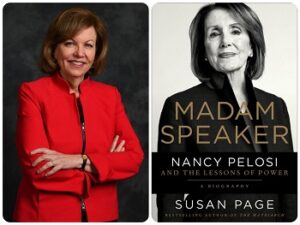

An Interview with Susan Page

by Kitty Kelley

Susan Page, Washington bureau chief for USA Today, has covered 11 presidential elections and interviewed 10 presidents. She appears regularly with Brian Williams on MSNBC and moderated the 2020 vice presidential debate between Mike Pence and Kamala Harris. Page has won several awards for her journalism, including the Merriman Smith Award and the Gerald R. Ford Prize for Distinguished Reporting on the President. Her first book was The Matriarch: Barbara Bush and the Making of an American Dynasty, and now she’s just written her second, Madam Speaker: Nancy Pelosi and the Lessons of Power.

Susan Page, Washington bureau chief for USA Today, has covered 11 presidential elections and interviewed 10 presidents. She appears regularly with Brian Williams on MSNBC and moderated the 2020 vice presidential debate between Mike Pence and Kamala Harris. Page has won several awards for her journalism, including the Merriman Smith Award and the Gerald R. Ford Prize for Distinguished Reporting on the President. Her first book was The Matriarch: Barbara Bush and the Making of an American Dynasty, and now she’s just written her second, Madam Speaker: Nancy Pelosi and the Lessons of Power.

Nancy Pelosi has been speaker of the House two times: 2007-2011 and again 2019 to the present. She’s indicated she’ll give up her gavel in 2022. Difficult to see her stepping down from the pinnacle of power to simply represent the 12th District of San Francisco, although she’s dean of the California delegation, having served in Congress since 1987. Do you see President Biden appointing her to be U.S. ambassador to Italy or the Holy See?

I do think this is likely to be Nancy Pelosi’s valedictory term in Congress. She indicated this would be her last term in the leadership when there was a challenge to her re-election as speaker after the 2018 elections.

You quote many Democratic reps and senators on the record saying positive things about the speaker. Considering we’re all God’s children, with a mixture of mischief and mayhem, do you feel you got to the essence of Pelosi, personally and professionally?

She’s a tough interview. She’s disciplined and guarded, when what an interviewer craves is someone who is exactly the opposite. But she became more candid and more open as I did more interviews with her (10 in all).

The speaker’s deep Catholic faith resonates throughout your book, but there’s not much evidence of humor. Is Pelosi all politics and no play?

Nancy Pelosi is close to her nine grandchildren, with whom she has relationships that can be whimsical. In the family chat, she’ll text heart emojis that can make them roll their eyes. When she was 76 years old, she took two grandsons to a Metallica concert. Pelosi and heavy metal: That’s a side to her that folks in Washington haven’t seen.

From your book, we see Pelosi demanding deference from Rep. Alexandria Ocasio Cortez following tweeted insults at the speaker from AOC’s administrative assistant. Soon after AOC met with the speaker, that assistant left AOC’s staff. Describe the current dynamic between the 80-year-old speaker and her 31-year-old colleague from the Bronx. Do you see any similarities between the two?

Pelosi told me that she sees similarities, especially with the younger Nancy Pelosi, who was demonstrating for single-payer healthcare and complaining about the compromises elected officials made to get half a loaf. Both women are smart and strategic, tough, and comfortable being disruptive. But there are big differences between them: Pelosi [today] is one of those elected officials who argues that getting half a loaf is better than none.

Do you think Pelosi’s corrosive relationship with President Trump disadvantaged Democrats and/or any legislation during the four years of Trump’s term?

One big example: A covid relief bill that was endlessly negotiated in 2020 and never enacted. It then passed soon after President Biden was inaugurated. She says she was holding out on principle. Even some Democrats complained that a deal could have been struck [earlier], and Republicans said she just didn’t want to give President Trump the political benefits of passage during [the campaign].

How did you get Newt Gingrich to endorse your book with the “advance praise” cited on the back cover? He praises Pelosi as “a professional…and a pirate.”

My secret strategy: I sent him the galleys.

Another Pelosi biography (Pelosi by Molly Ball) published last year described how President Obama refused to entertain Pelosi’s request to appear at her 25th-anniversary celebration. Did you interview Obama for this book about the woman who gave him his biggest legislative accomplishment by getting the Affordable Care Act passed?

I did have the opportunity to interview President Obama…[He and Pelosi] are bound in history. The Affordable Care Act, the biggest expansion of healthcare since Medicare and Medicaid, wouldn’t have passed without both Obama in the Oval Office and Pelosi in the speaker’s chair. He acknowledged that, even though the two sometimes clashed.

You mention the feud between Pelosi and former Rep. Jane Harman (D-Ca.), who, you write, felt that Pelosi was settling a personal score by denying Harman chairmanship of the House Intelligence Committee in 2011. What was the “personal score” that caused the rift between the two women, both Democrats from California?

That’s the subject of a lot of speculation. Some think it was policy; Harman was more hawkish on national security issues than Pelosi was. Some think it was personal, that they just didn’t get along. Whatever the truth, it delivered an unmistakable message to other House Democrats about the potential perils of being at odds with Nancy Pelosi.

From the public record, readers know about the strained relations between Pelosi and House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer (D-Md.). Have they ironed out their push-pull differences?

I detail the long and sometimes bitter campaign between [them] for Democratic whip — an insider campaign that lasted three years, involved millions of dollars in campaign contributions, and put Pelosi on the path to becoming speaker. This was a legislative battle waged largely behind the scenes that political scientists described as “titanic” and “unprecedented.”

Please relate your own experience with the speaker, which you describe in your book as “the full Pelosi” — that sent you home to recover over a glass or two of wine.

The Pelosi treatment! In my ninth interview…I was asking about an episode that she didn’t think warranted being in the book. I explained why I thought it did. She explained why she thought it didn’t. She never raised her voice, and she didn’t threaten me. But she somehow seemed to get taller than her five-five height, and her questions were so probing and pressing that I could feel the sweat popping on my forehead. In the end, I didn’t relent, and neither did she. But it gave me a better understanding of what it must be like to be a member of Congress she’s lobbying to vote for or against a bill.

Pelosi seems to have it all — a fabulous marriage, great children, loving grandkids, and good health, all while holding a world-shaking gavel. What’s her secret?

Success in the two worlds — personal and professional — may not be so different. Pelosi says that running a household of five children was the best possible training for running a House of disparate pols. You have to impose order amid chaos. Convince people to do what you want them to do, ideally by persuading them it was their idea. Deal with grievances, real and imagined. Forge alliances that are constantly shifting.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

The Age of Acrimony

by Kitty Kelley

The Age of Acrimony is an apt title for the combustible years of 1865-1915 when, according to the book’s subtitle, “Americans Fought to Fix Their Democracy.” That 50-year battle during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age bruised the country and left wounds we feel to this day. Jon Grinspan, curator of political history at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, creatively tells the story by wrapping the incendiary era around the lives of a Philadelphia congressman and his activist daughter.

The Age of Acrimony is an apt title for the combustible years of 1865-1915 when, according to the book’s subtitle, “Americans Fought to Fix Their Democracy.” That 50-year battle during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age bruised the country and left wounds we feel to this day. Jon Grinspan, curator of political history at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, creatively tells the story by wrapping the incendiary era around the lives of a Philadelphia congressman and his activist daughter.

The congressman, Rep. William Darrah Kelley (1814-1899), a lifelong abolitionist, abhorred slavery. In fact, Kelley’s opposition to slavery forced him to leave the 19th-century Democratic Party and travel to Ripon, Wisconsin, where he and other Northern congressmen formed the Republican Party.

His enemies called him “Pig Iron Kelley” because he represented the iron and steel districts of Pennsylvania as a fierce protectionist who always voted in favor of tariffs to shield the industry from foreign competition. His enemies called his daughter, Florence Kelley (1859-1932), a labor activist of stern demeanor, “that fire-eater in the black dress.”

Rep. Kelley arrived in Washington, DC, at the same time Abraham Lincoln moved into the White House. The  new president enjoyed meeting the new congressman because he could look him in the eye. The men, both long, lean, and lanky, became friends. Both were part of a new breed of “low-born but driven politicos,” replacing “the elite antebellum statesmen who had been born to be senators.”

new president enjoyed meeting the new congressman because he could look him in the eye. The men, both long, lean, and lanky, became friends. Both were part of a new breed of “low-born but driven politicos,” replacing “the elite antebellum statesmen who had been born to be senators.”

Both also belonged to an era when most Americans could get on a train “and tell, at a glance, how their fellow passengers would vote. Race, class, region, religion, occupation, ethnicity, even a style of hat or preference for [alcohol] all indicated Republican or Democrat.”

In those years, rural evangelical Yankees, Protestants, and upwardly mobile professionals who sipped whiskey in bars and wore snap-brim hats were Republicans, while Democrats were immigrant Catholics from the South who wore newsboy caps and drank ale in beer joints. They were the “stupider” party, “half Ku-Kluxer, half Irish-rioter.” Republicans were “moralistic crooks.”

Congressman Kelley, the abolitionist, represented Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where Blacks enjoyed the same nonexistent voting rights as their counterparts in Philadelphia, Mississippi. He also supported industrial laborers and women’s rights, but became famous for “speechifying,” the ticket to his national recognition.

He didn’t simply make speeches; he played bass, trumpet and trombone in his own orchestra of oration, riveting audiences with his “graveyard eloquence” and “cemetery roar.” Having been born into poverty, “He shouted his way to wealth” and built a mansion for his family called the Elms. Ironically, the man whose mesmerizing voice had roused thousands died from cancer of the jaw, tongue, and throat.

Kelley grew up with little formal education, having had to work all of his young life for wealth and position. His daughter grew up with all those privileges but, while she embraced her father’s progressive politics, she lacked his charisma.

When Florence was accepted for advanced study at Cornell, she bragged that she’d been “relieved of the burden  of the stupids.” An intense young woman, she intimidated guests when she accompanied her father to Washington parties. One journalist wrote, “The young girls in society were just a little afraid of her; the young men were not entirely at ease in her presence, and old legislators were very careful about statistics when talking to her.”

of the stupids.” An intense young woman, she intimidated guests when she accompanied her father to Washington parties. One journalist wrote, “The young girls in society were just a little afraid of her; the young men were not entirely at ease in her presence, and old legislators were very careful about statistics when talking to her.”

In April of 1865, President Lincoln asked Rep. Kelley to join the delegation to Fort Sumter to mark the end of the Civil War. “All was bright and beautiful and cheerful,” the congressman recalled of the trip. Then, en route to Washington, his ship passed a small boat whose captain shouted: “Why is not your flag at half-mast? Have you not heard of the President’s death?”

Grinspan describes the nation’s capital during those years as “a town of neighborhoods named Swampoodle and Murder Bay, centered on a National Mall fringed by a filthy canal, which stank like ‘the ghosts of twenty thousand drowned cats.’” Despite its stench, Washington, DC, held an allure no other city could match:

“New York had finer food, Boston had wittier writers and San Francisco had superior saloons, but Washington had power. And that power attracted, if not the wealthiest or the wisest, those most burning for place.”

Among those with aching ambition was William Jennings Bryan, renowned for his “Cross of Gold” speech; Lincoln Steffens, who revolutionized journalism; and Theodore Roosevelt, the first activist president, who most changed America in the years 1913-1920.

Not all historians write with the verve and dash of Grinspan, whose titles snap, crackle, and pop: “Where do all those cranks come from?” and “Reformers who Eat Roast Beef” and “Investigate, Agitate, Legislate.” For the most part, the chapters flow with narrative flair. For example, “Streetcar Number 126 wobbles its way up Lancaster Avenue into West Philadelphia” starts his foray into the central issue of the Gilded Age, which was not class, race, industrialization, or immigration, but rather the political paralysis that made addressing those issues impossible.

Sound a bit familiar?

It’s disheartening to read that the endemic voter suppression of 1892 lives on into 2021. (See current news coverage of the white, male legislators in Georgia who signed a bill behind closed doors to restrict Black voters.) The social and economic upheavals of more than 100 years ago, plus the searing political partisanship that undermined faith in democracy at that time, are all too recognizable today.

Yet Grinspan’s history of the era does not despair for democracy. In fact, he pummels Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), the English writer born in India who visited America and left with disdain, saying democracy was rotten and the U.S. was doomed by bars full of “strong, coarse, lustful men.” Grinspan, marshaling arguments to the contrary, proves Kipling’s facts unfounded and concludes: “America digested the famous writer and expelled him out its other end.”

Grinspan contends that 20th-century democracy has grown more reasonable, more enlightened, and more transparent. “The tribal, nearly biological view of partisanship, and demonization of the rival party as ‘enemies of the human race’ has weakened.”

Hmm. Reading that in 2021 while still feeling the whiplash of Donald Trump’s presidency, one might wonder but still take hope in the author’s conclusion that our democracy is elastic, “with plenty of room for ugliness without apocalypse, and for reform without utopia.”

Crossposted with Washngton Indedependent Review of Books

The Barbizon

By Kitty Kelley

By Kitty Kelley

Back in the day (circa 1930-1960), small-town girls with big-city dreams headed for New York and checked into the Barbizon Hotel for Women at 63rd and Lexington. Upon arrival, they were greeted by doorman Oscar Beck, welcomed by Connor, the hotel manager, and scrutinized by the front desk matron, Mrs. Sibley, who allotted the best of the sliver-sized rooms to “the Daisy Chain,” those who attended one of the Seven Sisters: Barnard, Smith, Mount Holyoke, Vassar, Bryn Mawr, Wellesley, and Radcliffe. Everyone else had to provide social references and three letters of recommendation.

As Paulina Bren writes in The Barbizon: The Hotel That Set Women Free: “In the national imagination it was understood that the East Coast was the country’s intellectual hub while the rest of the country remained its backwater.”

During the era of white gloves, pillbox hats, and hose and high heels, the Barbizon (rhymes with bygone) offered 22 floors of “gracious living” in “utmost security” (no men allowed above the lobby), plus a rooftop garden terrace, a swimming pool, artists’ studios, a coffeeshop, formal dining room, solarium, library, and the Corot Room for Thursday teas, complete with a pianist.

From 1927 to 2005, the Barbizon was the ne plus ultra for young women seeking careers as artists, writers, dancers, singers, and actresses. For those without such talents, there was the Katherine Gibbs Secretarial School, which reserved several floors at the hotel with imposed curfews, house mothers, and skirt police, who barred wearing slacks in public.

Mademoiselle magazine also reserved Barbizon rooms for their “Millies,” as guest editors were called. These competitively selected coeds (15-20) from colleges around the country arrived every June for glamorous month-long internships to produce the magazine’s August back-to-school issue. The modeling agencies of John Powers and Eileen Ford booked several floors of the hotel for their aspirants, as did the Parsons School of Design, the Tobe-Coburn School of Fashion Careers, and the Junior League.

Over the years, the Barbizon burnished its image as a dormitory for debutantes. During World War II, when General “Wild Bill” Donovan put out a call for women to come to work for the Office of Strategic Services, precursor to the CIA, he said his ideal would be “a cross between a Smith College graduate, a Powers model, and a Katie Gibbs secretary.”

The list of Barbizon alumnae includes Grace Kelly, Gene Tierney, Lauren Bacall, Joan Didion, Ali MacGraw, Tippi Hedren, Joan Crawford, Jaclyn Smith, Gael Greene, Nora Ephron, Ann Beattie, Betsey Johnson, Candice Bergen, Liza Minelli, Cybill Shepherd, Elaine Stritch, Cloris Leachman, and Molly Brown, the Titanic’s most famous survivor. Even Edith “Little Edie” Bouvier, star of the documentary “Grey Gardens” and the cousin of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, lived at the hotel from 1947-52, until she was called home by her mother, Big Edie, to take care of her and the cats.

The Barbizon has been featured in novels like Mary McCarthy’s The Group, The Best of Everything by Rona Jaffe, Searching for Grace Kelly by Michael Callahan, and, most famously, The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath, a 1953 “Millie” who used the experience to write her only novel. Authors Jacqueline Susann, Jackie Collins, and Judith Krantz followed suit by placing characters in women-only residences like the Barbizon — now a condominium listed in the National Register of Historic Places and designated a city landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Given its history and colorful residents, the Barbizon deserves bookshelf space alongside other high-profile-building biographies: Life at the Dakota: New York’s Most Unusual Address by Stephen Birmingham; 1185 Park Avenue by Anne Roiphe; House of Outrageous Fortune: Fifteen Central Park West, The World’s Most Powerful Address by Michael Gross; and The Plaza: The Secret Life of America’s Most Famous Hotel by Julie Satow.

As a Vassar College professor of gender and media studies, Bren brings impressive academic credentials to her history of the Barbizon. Unfortunately, her book’s subject, at least in her telling, does not live up to its billing as “the hotel that set women free.”

Rather, the Barbizon that Bren presents seems to have been primarily a secure waystation for young women who wanted to experience living in Manhattan before they got married. According to (and reiterated endlessly by) the author, marriage was always the end goal: the brass ring on life’s merry-go-round. Anyone residing at the Barbizon past her sell-by date of four years without a marriage proposal was headed for a lifetime of misery (i.e., spinsterhood).

“As bold as one might be, however big one might dream, as a young woman you knew that the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow was marriage,” Bren writes. “[It] had to be marriage. Even if part of you longed to be actress, writer, a model or artist…[A]ll the women at the Barbizon shared the ultimate goal — marriage.”

Bren bangs that drum throughout, writing of the young women staying at the hotel: “Their time at the Barbizon  [was] a short window of opportunity that would usher them toward the ultimate goal of marriage.” To the regrettable exclusion of the hotel’s dozens of other notable residents, the author seems transfixed by the morbid memory of Plath, who committed suicide in 1963 at the age of 30, while separated from her husband.

[was] a short window of opportunity that would usher them toward the ultimate goal of marriage.” To the regrettable exclusion of the hotel’s dozens of other notable residents, the author seems transfixed by the morbid memory of Plath, who committed suicide in 1963 at the age of 30, while separated from her husband.

“It was her final, successful suicide attempt, with the first right after June 1953, and others most probably in between,” writes Bren. Readers might wonder if her editor was AWOL, searching for “others most probably in between,” because the author provides no documentation in her text or chapter notes.

The threnody of Plath’s suicide haunts many of the chapters of this book, as The Bell Jar was an homage to the Barbizon, which Plath the novelist renamed the Amazon. As one of the “Millies” wrote after a 2003 reunion at the hotel: “Do you find it as unpleasant as I that the reunion would not have taken place had Sylvia not stuck her head in the oven?”

One could say the same about this book.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

I Am, I Am, I Am

by Kitty Kelley

Before Maggie O’Farrell wrote Hamnet, her award-winning 2020 novel that reimagines the life and death of Shakespeare’s only son, she examined her own life and death in a memoir entitled I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death.

Before Maggie O’Farrell wrote Hamnet, her award-winning 2020 novel that reimagines the life and death of Shakespeare’s only son, she examined her own life and death in a memoir entitled I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death.

While most people fear what W.C. Fields called “the man in the bright nightgown,” O’Farrell claims to be sanguine about death, and she makes her case as someone who has outwitted the scythe 17 times in 49 years. Still, if not for her luminous writing, the book might not beckon.

O’Farrell takes her title from Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, a fictional descent into madness in which the protagonist survives suicide and lives to feel her brave heart beat evenly: “I took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart: I am, I am, I am.” That regular rhythm signals life, and O’Farrell’s book offers an affirming message about escaping death.

In 17 short chapters about the 17 body parts affected by her own near-fatal experiences, O’Farrell hopscotches across time to recount her gambols with the Grim Reaper, including “Neck (1990),” “Body and Bloodstream (2005),” and “Cerebellum (1980).” Each essay is introduced with a sketch of the part — neck or body and bloodstream or brain — to be discussed.

She thinks there is nothing unique about a near-death experience and claims they’re not rare:

“[E]veryone, I would venture, has had them…perhaps without even realizing it. The brush of a van too close to your bicycle, the tired medic who realizes that a dosage ought to be checked one final time, the driver who has drunk too much…the aeroplane not caught, the virus never inhaled.”

As a child, she writes, she was an escapologist. “I ran, scarpered, dashed off, legged it whenever I had the chance…I wanted to know, wanted to see, what was around the next corner, beyond the bend.”

At the age of 8, the super-charged little girl’s life changed forever: She woke up with a headache and could not walk. She had contracted encephalitis. She was close to death and hospitalized for weeks with fever, pain, and immobility. Suddenly, she was a child who could barely hold a pen, who had lost the ability to run, ride a bike, catch a ball, feed herself, swim, climb stairs, and skip. She was a child who traveled everywhere in a humiliating, outsized buggy.

From the hospital, O’Farrell was blanketed like a baby and carried home to spend many more months in bed, and then a wheelchair, followed by hydrotherapy and physiotherapy, and finally recovery. She recalls that searing experience as “the hinge on which my childhood swung”:

“Until that morning I woke up with a headache, I was one person, and after it, I was quite another. No more bolting along pavements for me, no more running away from home, no more running at all. I could never go back to the self I was before.”

Without self-pity, she recites the illness’ devastating aftereffects: As an adult, she loses her balance and can’t walk a straight line or stand on one foot. She frequently falls over, drops silverware, and cannot cycle long distances.

The self she became — her after-self — was dogged by disappointment, dashed dreams, and near death. She loses her track to a Ph.D. and an academic career at the age of 21 because of inadequate grades; she nearly drowns in a riptide; she is held up at knife point; and she bolts from a live-in boyfriend after finding a flesh-colored bra under the bed that is not hers.

After the latter incident, she waits “the requisite time” for a virus to appear, grabs her gay friend, and insists they go to a clinic to get tested. The receptionist gives each a page to fill in about previous sexual encounters. Her friend looks at the form and delivers the only risible line in this book: “Do you think you’re allowed to ask for extra paper?” he asks “a little too aloud.” (Needing comic relief from O’Farrell’s unremitting woes, I, too, laughed a little too aloud.)

O’Farrell writes luscious sentences about grim subjects, particularly her attempts to conceive, only to have to cope with a wretched miscarriage:

“Something is moving within me, deep in the coiled channels of my stomach, something with claws, with fangs, and evil intent…It is as though I have swallowed a demon, a restive one that turns and fidgets, scraping its scales against my innards.”

She suffers so many miscarriages that she and her husband refer to the doctor’s office as “the bad-news room.” Later, when she finally carries a pregnancy to term, she spends three agonizing days in labor — an excruciating experience considering the average labor for a first-time mother is six to 15 hours.

She faults “the highly politicized arena of elective Caesareans in the U.K.” and excoriates as a butcher the British doctor who kept denying her a C-section. She describes the surgery in such visceral detail that you cringe, almost feeling the surgeon slice across her stomach and the nurses wrestling and grappling and clutching and heaving, until finally her body ruptures, spraying blood everywhere. Another near-death experience, but one that produces her first child.

All the literary reading that O’Farrell poured into her doctoral studies is on fine display in these pages. Among others, she references Shakespeare, Thomas Hardy, Seamus Heaney, Arthur Miller, Hilary Mantel, Robert Frost, Mark Twain, and Andrew Marvell’s “winged chariot,” which carries her into elegant riffs with a scholar’s vocabulary:

“The wave turns me over…like St. Catherine in her wheel”; “like Brueghel’s Icarus falling into the waves”; “the stifling anhydrous scent of sawdust”; “with a tiny rhomboid of garden”; “watched from the ceiling by a leucistic gecko…”

In I Am, I Am, I Am, Maggie O’Farrell rings all the bells for impressive prose, albeit on a subject of little poetry.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Widowish

by Kitty Kelley

Death never knocks gently except for those lucky few who’ve lived long, full lives and go to bed one night to wake up with the angels. For everyone else, the knock on the door is fraught, and particularly devastating for those who are young and in the happy throes of living.

Death never knocks gently except for those lucky few who’ve lived long, full lives and go to bed one night to wake up with the angels. For everyone else, the knock on the door is fraught, and particularly devastating for those who are young and in the happy throes of living.

Death began stalking Joel Gould shortly after he arrived at the emergency room with flu-like symptoms. He and his wife, Melissa, had been dealing with his multiple sclerosis for a few years, as the autoimmune disease gradually affected his balance and muscular control, leaving him unable to play basketball, ride his bike, or even walk to work.

They’d told their young daughter he had MS — withholding the frightening specifics — but kept the diagnosis secret from the rest of their family and friends in order to avoid questions with morose answers.

Three days after Joel entered that hospital, he was put in the intensive care unit and placed on life support while doctors told Melissa that he was “gravely ill.” She screamed at them. “We’re in a hospital. You’re all doctors. If Joel is sick, make him better…We have a thirteen year old daughter.”

Upon the recommendation of their family doctor, Melissa moved her husband to a teaching hospital where specialists tried to determine his worsening condition. “He had another MRI. A brain angiogram. A spinal tap. Several EEGs to monitor brain activity. More blood work. More cultures.” Finally, they diagnosed West Nile virus, which had decimated Joel’s compromised immune system, leaving him paralyzed and brain dead.

One of the doctors asked Melissa what she’d meant when she’d said quality of life was important to her husband. “Having just turned fifty years old, he did not want to end up in diapers,” she writes.

The doctor then asked if that meant Joel wanted to be someone capable of living independently.

“Yes, absolutely,” she said.

“Well…it looks that as of now, the kind of recovery we can hope for is that he may be able to hold a comb one day. But he wouldn’t know what to do with it.”

Death had just rammed open the door of Melissa Gould’s life, leaving her bereft and crazed with grief. Knowing her husband would never recover, she allowed him to be taken off life support, but, at the age of 46, refused to be defined as a widow. The word revolted her:

“Widow once described a much older woman. Old, wrinkled, tragic. Wearing black. Maybe even a veil…[I was] a mom with blonde highlights going to yoga, picking up her daughter from school, buying groceries at Trader Joe’s…I didn’t look like a widow.”

To her, “widow” was an ugly word hanging from the mottled neck of a woman with grey hair and yellow teeth. Even now, years after her husband’s death, she called fellow widows and widowers “wisters” — widow sisters and widow misters. Hence, she titled her memoir Widowish, as if a little suffix can soften the whiplash.

Perhaps this is understandable for a pop-culture princess from Southern California like Melissa, who writes about regular hikes on a hill she calls “the Clooney,” because it’s near an L.A. house owned by George Clooney. Sometimes she makes the climb with her “bestie,” who’s “the Gayle to my Oprah.”

She defines herself as “simply Jew-ish,” writing: “Outside of my liberal and cultural connection to Judaism, I just didn’t connect.” Her Jewish husband connected completely, however, which is why she’d called a rabbi to his bedside. “I knew Joel would have welcomed a visit without hesitation.”

Her devotion to her spouse is undeniable as she weaves the story of their marriage into surviving without it. She writes that when they met, she felt like she’d hit the trifecta. “He was cool. He was funny. He was Jewish.”

He was also in a committed relationship, but they bonded over their shared passion for music. When she told him she was leaving for Seattle to write for a television show, he summoned his best impersonation of Daniel Day-Lewis in “The Last of the Mohicans”: “Stay alive, no matter what occurs! I will find you!”

She became enthralled with Seattle as “the epicenter of the biggest shift the music business had seen in decades — grunge — Kurt Cobain was still alive…I was in heaven.” A few months later, Joel, also in the music business and recently separated, showed up. “We didn’t stop kissing the entire few days he was in Seattle.”

They married, moved back to California, and had one child, although they’d hoped to have many. Melissa writes seamlessly about caring for their daughter after Joel’s death, keeping to the youngster’s schedule, getting her to school on time, making her meals, helping with homework, and curling up in bed with her every night “to talk about Daddy.”

Few people forge through the miasma of grief without help, which is why believers light candles and liquor stores open early. Melissa found her way by watching “Real Housewives” religiously, listening to TV evangelist Joel Osteen preach his “attitude of gratitude” gospel, and embracing New Thought guru Iyanla Vanzant as her life coach.

“Grief is personal and private,” Melissa writes, but hers never was. She shared it with her friends, her family, a man at the car wash, her hairdresser, and all the cashiers at the supermarket. “I was in midlife, barefoot in shiva clothes and a blowout. I felt compelled to tell people I was a widow because I didn’t look like one.” She wrote about her grief in the New York Times and the Huffington Post, which led finally to this book.

Searching for guidance, she went to a “highly recommended” psychic named Candy. Melissa presented Joel’s watch and photograph because “it helps channel or receive information.” Within minutes, Candy claimed she was connecting with Melissa’s dead husband. She said there would be a new man in her life soon with a son, and that Joel approved of the relationship.

“That’s what he wants me to tell you,” said Candy.

Melissa writes that she laughed off the prediction until she met Marcos — and then his son — a few weeks later. Six months after kissing her husband goodbye, Melissa begins “to live again” by dating Marcos. At this point, some “wisters” might be envious, while others may tsk-tsk, but Melissa Gould is a Hollywood writer who has read Cinderella. She knows the value of a happily-ever-after ending.

She and Marcos and their children now live together near Simi Valley, where Melissa runs a writing workshop at Camp Widow, part of a nonprofit called Soaring Spirits International, where she guides people in healing by exploring the unexpected realities of being a widow. Yes, she can finally face that word without the “ish.”

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Robert E. Lee and Me

by Kitty Kelley

Early in the Civil War, the Union Army seized “Arlington” — Robert E. Lee’s 1,100-acre estate across the Potomac from Washington, DC — and used it to headquarter federal troops. Lee never returned to his home, but he sued his country for damages after the war and collected more than $4 million.

Early in the Civil War, the Union Army seized “Arlington” — Robert E. Lee’s 1,100-acre estate across the Potomac from Washington, DC — and used it to headquarter federal troops. Lee never returned to his home, but he sued his country for damages after the war and collected more than $4 million.

When debate about the property seizure reached the U.S. Senate, Charles Sumner, who led that body’s anti-slavery forces, railed against the slaveholding Confederate general, saying: “I hand him over to the avenging pen of history.” That pen has now been wielded to dazzling effect by Ty Seidule in Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner’s Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause.

Few others could write this book with such sterling credibility. Only a man of the South, a Virginian, and a soldier with a Ph.D. in history could so persuasively mount the case against a national hero, and label him a traitor. For even today, the image of Lee, who fought against his country to preserve slavery, is revered with monuments, parks, military bases, counties, roads, schools, ships, and universities named in his honor. Yet, armed with years of documented research, Seidule demonstrates that Lee, like Judas, was guilty of base betrayal.

“It’s an easy call,” he writes at the end of his stunning book, “because Lee resigned his commission, fought against his country, killed U.S. Army soldiers, and violated Article III, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution. Lee committed treason.”

It wasn’t always an easy call for Seidule, a retired U.S. Army brigadier general who taught at West Point for 16 years and spent many of those years trying to understand why America’s premier service academy had so many monuments honoring Lee. “I went to the archives and spent years studying…that process changed me. The history changed me. The archives changed me. The facts changed me.”

As a boy, Seidule read Meet Robert E. Lee, “my childhood bible.” And “growing up in Virginia I worshipped Lee, the Confederate general.” Seidule attended Washington and Lee University in Lexington City, Virginia, where Lee Chapel features a statue of the general lying on the altar, but nothing else: no hymnals, no Book of Common Prayer, and no Ten Commandments (as the first one is: “I Am the Lord Thy God and Thou Shalt Not Have False Gods Before Me”).

“My school worshipped Robert E. Lee, literally,” Seidule writes. “[He] was God, and his Confederate cause was the one true religion.” He admits, somewhat shamefully, that he, too, once believed “all the lies and tropes.”

Lee’s body lies in a white marble sarcophagus under Lee Chapel alongside the remains of his faithful steed, Traveller. Visitors place carrots and apples on the horse’s grave, along with pennies — “Always heads down. No one wanted to have the hated Lincoln’s face visible to Lee’s grave.”

While slavery was abolished in 1863, Seidule learned that slaveholders continue to be honored to this day. He reports that Confederate monuments at 34 cemeteries in the U.S. are kept up by the government at taxpayer expense. “Over the last ten years federal and state governments have paid more than $40 million to maintain memorials to Confederate treason and racism with only a pittance going to African American cemeteries from the slave era.” As an Army officer, he’s particularly irate about the monument at Arlington National Cemetery:

“That angers me the most because every year the President of the U.S. sends a wreath ensuring the Confederate monument there receives all the prestige of the U.S. government…among the 400,000 soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines buried on those hallowed grounds are my friends, colleagues and family.”

Most Confederate monuments, including those honoring Lee, were erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in the early 20th century to preserve the glorious myth of the Lost Cause — a Southern euphemism for inglorious defeat:

“[Those monuments have] the same purpose as lynching: to enforce white supremacy. It is no coincidence that most Confederate monuments went up between 1890-1920, the same period that lynching peaked in the South. Lynching and Confederate monuments served to tell African Americans they were second-class citizens.”

The United Daughters of the Confederacy sprayed perfume on the stench of slavery and fluttered swan’s-down fans as they fashioned the Civil War as “the war of Northern aggression.” Seidule rightly calls it the war over slavery, and most responsible historians agree. But the author admits that while the South lost the war, they won the battle for the narrative.

No one did more to promote that narrative — moonbeams and magnolias, happy slaves and beloved masters — than Margaret Mitchell, who wrote Gone with the Wind, which has sold over 30 million copies to become the second most-popular book in America, next to the Bible. As the poet Melvin Tolson (1895-1966) wrote, “[That book] is such a subtle lie that it will be swallowed as the truth by millions of whites and blacks alike.”

The most damning indictment against Robert E. Lee is found in his own letters, which refer to the Emancipation Proclamation as “a savage and brutal policy,” words that aptly describe Lee’s treatment of his slaves, as verified in testimony given by one enslaved worker who had tried to escape from “Arlington” with his sisters. They were captured and punished:

“[Lee] ordered his constable to lay [the whip] on well with fifty lashes for [the man] and twenty for his sisters. After the whippings on their bare backs, Lee ordered salt water poured over their lacerated flesh.”

Ty Seidule writes with the passion of a convert who’s seen the light and needs to shine it for other to save them from “the lies and tropes” that blinded him for so many years. Robert E. Lee and Me is a cri de coeur, one man’s journey to humanity and his salvation from the pernicious lies of white supremacy.

Crosssposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

(Kitty Kelley interview with Ty Seidule here.)

Henry Adams in Washington

by Kitty Kelley

If an academic book is one that can be taught in college, then Henry Adams in Washington: Linking the Personal and Public Lives of America’s Man of Letters succeeds. In fact, this book by Ormond Seavey, an English professor at George Washington University, reads like a semester’s course on why Henry Adams ought to be elevated to the pantheon of 19th-century writers alongside Mark Twain, Henry James, Edith Wharton, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau.

If an academic book is one that can be taught in college, then Henry Adams in Washington: Linking the Personal and Public Lives of America’s Man of Letters succeeds. In fact, this book by Ormond Seavey, an English professor at George Washington University, reads like a semester’s course on why Henry Adams ought to be elevated to the pantheon of 19th-century writers alongside Mark Twain, Henry James, Edith Wharton, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau.

Seavey maintains that Adams (1838-1918) has been deprived of his rightful place in the literary stratosphere and proposes restoration. He starts by stating that the writer’s nine volumes entitled History of the United States of America (1801-1817) “belong alongside the greatest works of American creative writers.”

Further, he asserts the books comprise “the greatest work of history composed by an American…yet…unacknowledged in its own country,” and he intends to bring Adams the recognition he feels he deserves in the U.S. The professor concedes some literary critics might disagree with him, but he presents his case with pedagogical fervor and a few too many convoluted sentences:

“[Adams’] Washington turns out to be an essentially imaginative construct whose dimensions and appearances correspond to what others experience except that he has converted those details into a complex notion somehow independent of the seemingly solid realities experienced, for example, by James Madison, John Randolph, Ulysses S. Grant, Henry Cabot Lodge, or Theodore Roosevelt.”

Seavey scores high on presenting Adams as a man of letters but falls short on illuminating the personal side of the man. Publicly, Adams was known as a Boston Brahmin with a prestigious lineage: President John Adams (1735-1826) was his great-grandfather, and President John Quincy Adams (1767-1848), his grandfather. He made his own mark as a noted historian and novelist.

Yet even 100 years after his death, the personal man remains elusive because, for reasons Seavey doesn’t explain or explore, Adams resisted transparency. Other than his multi-volume history, he refused to publish under his own name and sometimes went to great lengths to camouflage his authorship. Why remains unknown.

When Adams worked for his father, Charles Francis Adams Sr., in the House of Representatives, he wrote anonymously as the Washington correspondent for Charles Hale’s Boston Daily Advertiser. Later, when his father became Abraham Lincoln’s ambassador to the Court of St. James, Adams worked as his father’s private secretary and wrote anonymously as the London correspondent for the New York Times.

Was he anonymous because of conflicts of interest between working in politics while working as a journalist? Seavey doesn’t say; he simply describes Adams as “that master of conspiracies and disguises.”

After Adams married and moved to Washington, he wrote two novels, each one blanketed in secrecy: Democracy, which Seavey describes as “a novel disguised as autobiography,” was published anonymously, and Esther, which was published under the female pseudonym Frances Snow Compton.

Why the camouflage? Seavey suggests that Adams hid behind a skirt because he was unwilling to have his DC neighbors know he was the one exposing the city’s deficiencies. If his novels, based on real people, were published under his name, he may have jeopardized his social status in Washington, where he and his wife, Clover, John Hay and his wife, Clara, and Clarence King, a pioneering geologist and entrepreneur, formed an elite little club they called “The Five of Hearts,” the title of Patricia O’Toole’s spectacular 1990 biography, which was subtitled “An Intimate Portrait of Henry Adams and His Friends, 1880-1918.”

That loving quintet splintered on December 6, 1885, when Clover Adams, 42, committed suicide by swallowing potassium cyanide. The evening newspaper reported she had dropped dead from paralysis of the heart, which may have been strangely accurate, because the writings of others indicate she knew her husband had fallen in love with another woman, Elizabeth Sherman Cameron.

That Christmas, days after his wife’s death, Adams sent Cameron a piece of Clover’s favorite jewelry, requesting she “sometimes wear it, to remind you of her.” He had been writing Cameron passionate letters since 1883, two years before his wife took her life, and continued for the next 35 years of his life, although, according to Eugenia Kaledin’s The Education of Mrs. Henry Adams, their relationship was never consummated.

These personal details are ignored by Seavey, although available in the biography of Adams written by Ernest Samuels (1903-1996), who received the Parkman Prize, the Bancroft Prize, and the 1965 Pulitzer Prize for his three-volume study. Yet Samuels is not listed in Seavey’s bibliography and is only cited once in passing, a strange omission in a book purporting to link “the personal and public lives of America’s man of letters.”

These personal details are ignored by Seavey, although available in the biography of Adams written by Ernest Samuels (1903-1996), who received the Parkman Prize, the Bancroft Prize, and the 1965 Pulitzer Prize for his three-volume study. Yet Samuels is not listed in Seavey’s bibliography and is only cited once in passing, a strange omission in a book purporting to link “the personal and public lives of America’s man of letters.”

The most intriguing monument to the mystery of Adams is the bronze sculpture he commissioned in memory of his wife, frequently called “Grief.” “Henry Adams left it to August St. Gaudens to preserve forever the experience of [his] loss. Visitors to Rock Creek Cemetery [in Washington, DC] can see it for themselves. And that is all I am going to say about that,” Seavey writes.

The professor ends his book a few pages later, having shown in full the public life of Henry Adams but leaving his personal side in shadows, still detached and disparate.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books