Passionate Mothers, Powerful Sons

by Kitty Kelley

During the pandemic, Charlotte Gray scored a win for women. The Canadian author spent her lockdown days examining the lives of two American mothers previously disregarded by male historians as mere accessories to their world-conquering sons. The result is a feminist take on the women, who’ve been derided and diminished for decades: Jennie Jerome Churchill, once depicted as a fashion-crazed flibbertigibbet, and Sara Delano Roosevelt, dismissed as a wealthy harridan.

During the pandemic, Charlotte Gray scored a win for women. The Canadian author spent her lockdown days examining the lives of two American mothers previously disregarded by male historians as mere accessories to their world-conquering sons. The result is a feminist take on the women, who’ve been derided and diminished for decades: Jennie Jerome Churchill, once depicted as a fashion-crazed flibbertigibbet, and Sara Delano Roosevelt, dismissed as a wealthy harridan.

“They’ve been shoehorned into harmful stereotypes,” writes Gray, “and rarely been portrayed in a sympathetic light since their deaths. In fact, their sons’ biographers often disparage them — it is as though the Great Men of History must spring like Athena, fully formed from the head of Zeus, without tiresome interventions from their mothers.”

Most of those who’ve examined these so-called “great men” are themselves men, including respected biographers William Manchester, author of the three-volume The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill; Andrew Roberts (Churchill: Walking with Destiny); Alan Brinkley (Franklin Delano Roosevelt); and H.W. Brands (Traitor to His Class: The Privileged Life and Radical Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt).

Now comes a reassessment of both in Passionate Mothers, Powerful Sons: The Lives of Jennie Jerome Churchill and Sara Delano Roosevelt. Gray, who’s written 12 literary nonfiction books, is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. Relegated to mining secondary sources of previously published material, she nonetheless manages to bring a compelling view to the life stories of two mothers who influenced the world through their sons.

Both women were unicorns, each one of a kind but complete opposites of each other. Jennie Jerome, who wed Lord Randolph Churchill, was the most famous American heiress to cross the Atlantic and marry a title during the Gilded Age of 1870-1914. As Lady Churchill, she kept her status through three marriages while enjoying numerous dalliances with paramours said to include a Serbian prince, a German nobleman, several British aristocrats, and the prince of Wales, who admired American women because “they are livelier, better-educated, and less hampered by etiquette…not as squeamish as their English sisters.” Jennie became a favorite of the latter, the future King Edward VII, and used her golden contacts to enhance her son’s prospects. As Winston said, “She left no wire unpulled, no stone unturned, no cutlet uncooked.”

Once Winston married, his mother lost her premier place in his life. But whereas Jennie loathed the role of grandmother, Sara Delano Roosevelt reveled in it. On one occasion, when FDR’s two youngest sons were disciplined by having their pony taken away, Sara bought each little boy a horse. Naturally, all the Roosevelt grandchildren adored their grandmother, leaving their mother embittered. As Eleanor Roosevelt wrote years later, “As it turned out, Franklin’s children were more my mother-in-law’s children than they were mine.”

Also unlike Jennie Churchill, Sara Roosevelt enjoyed lifetime access to elite society and did not color outside the lines of proper protocol. Following her husband’s death, the dowager aristocrat donned widow’s weeds and never considered remarriage. Living like a vestal virgin, Sara dedicated herself to her only child, the future American president, following him to Harvard and living near campus so she could see him for dinner once a week. When Franklin married, his mother enlarged her homes at Campobello, in Manhattan, and at Hyde Park to accommodate his growing family, providing them with nannies, maids, laundresses, cooks, and drivers. She even advised her son professionally, counseling him after he won his first political appointment: “Try not to write your signature too small…so many public men have such awful signatures, and so unreadable.”

Spoiled and indulged by adoring mothers, Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt possessed galloping self-confidence that bordered on arrogance and made each insufferable to colleagues. As Churchill said when he returned from the Boer Wars a national hero, “We are all worms, but I do believe that I am a glow-worm.”

Not surprisingly, each of these two egoists had little regard for the other. As FDR told Joseph Kennedy after appointing him U.S. ambassador to the Court of St. James, “I have always disliked [Churchill] since I went to England in 1918 [as assistant secretary of the Navy]. He acted like a stinker then, lording it over all of us.”

Fortunately, their relationship changed when Churchill became prime minister of Great Britain, Roosevelt was commander-in-chief of the United States, and the world was at war. But their closeness — and, indeed, FDR’s prominent place in history — might never have evolved had it not been for the fierce intervention of Sara Delano Roosevelt.

Returning home from London in 1918, Franklin had come down with Spanish flu exacerbated by double pneumonia. His mother and his wife met his ship in New York and had him carried on a stretcher to Sara’s home on East 65th. Street. As the orderlies struggled to make Roosevelt comfortable, Eleanor began unpacking his suitcases and there found love letters from Lucy Mercer. Devastated, she marked that moment as life-changing: “The bottom dropped out of my world.”

Tearfully confronting her husband — as did his mother — Eleanor offered to grant him a divorce. Sara roared back in horror. Furious at her son’s moral lapse, yet fearing the shame a divorce might bring to the family, she declared that if he left his wife, he’d be leaving her as well — and that included Sara’s vast fortune, which supported him, his five children, and his future political prospects. Franklin made the pragmatic decision to remain in the marriage; Eleanor permanently moved out of their bedroom.

Back in London, after years of being chased by unscrupulous money-lenders and litigious creditors, Jennie Jerome Churchill died a grotesque death in 1921. At age 67, she fell down a staircase while wearing a new pair of high heels. “Life didn’t begin for her on a basis of less than forty pairs of shoes,” said Winston’s secretary about Jennie’s unchecked extravagances and staggering debts. Within days of breaking her ankle, gangrene set in, necessitating amputation of her leg above the knee. Lady Churchill soon slipped into a coma and expired, leaving Winston inconsolable. For the rest of his days, he kept a bronze cast of his mother’s hand on his desk.

Sara Roosevelt, however, lived a long and enviable life. She saw a beloved son crippled by polio rise to become president of the United States three times. At his third inauguration, she proudly proclaimed herself “a mother of history,” saying that few mothers ever lived to see their sons elected once. “Why, when you read history it seems as if most of the Presidents didn’t have mothers, the way they fail to appear in the accounts.” At the age of 86, Sara wrote to her son:

“Perhaps I have lived too long, but when I think of you and hear your voice I do not ever want to leave you.”

Alas, Roosevelt’s adoring mother took her final leave on September 7, 1941, and within four years, as he was starting an unprecedented fourth term as chief executive, her “precious son” would follow her at the age of 62 after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage at the Little White House in Warm Springs, Georgia.

In this provocative biography, Charlotte Gray bestows revisionist interest on two “passionate mothers” whose “powerful sons” proved themselves worthy of the maternal love and devotion showered on each.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Letters for the Ages

by Kitty Kelley

Nazi troops began studying English phrasebooks to prepare for their invasion of Great Britain. France had fallen under Germany’s Blitzkrieg in June 1940, following the capitulation of Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. Swastikas papered Paris to welcome Hitler.

Nazi troops began studying English phrasebooks to prepare for their invasion of Great Britain. France had fallen under Germany’s Blitzkrieg in June 1940, following the capitulation of Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. Swastikas papered Paris to welcome Hitler.

Across the Channel, Great Britain’s prime minister addressed his country on the radio and summoned them to what he pronounced would be their finest hour: “Hitler knows he will have to break us in these islands or lose the war. If we can stand up to him all Europe may be freed, and life for the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands.”

Over the airwaves, Winston Churchill spoke eloquently as he inspired his nation. Behind the scenes, he churned with rage, lashing out at everyone. In desperation, his privy council begged his wife to intercede.

Clementine Churchill knew that her husband would pay attention to a letter, and so she labored over one, rewriting her pages twice before she found the right words. “My Darling Winston,” she began, “I hope you will forgive me if I tell you something I feel you ought to know.” Then, with care and consideration, Mrs. Churchill, self-described as “loving devoted & watchful,” told her ferocious husband that he’d been “rough, sarcastic and over-bearing” to his colleagues and subordinates.

Prim as a schoolmarm disciplining an unruly student, Clementine instructed urbanity, kindness, “and if possible Olympic calm.” She further recommended that the prime minister, who had the power to “sack anyone & everyone,” except for the king, the archbishop of Canterbury, and the speaker of the House of Commons, curb his “irascibility & rudeness. They will breed either dislike or a slave mentality — (Rebellion in War time being out of the question!).”

Unfortunately, Letters for the Ages, a treasure trove of Churchill’s correspondence, doesn’t contain the lion’s response to the lioness, but its editors claim to “be fairly certain that he listened to his ‘devoted & watchful’ cat.” Clementine kept her letter as part of the historical record, as an insight into their relationship, and as an important glimpse into the pressures of wartime leadership.

Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (1874-1965) wrote 40 books in 60 volumes and won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1953. Trumpeted by YouTube as “Britain’s Greatest Prime Minister,” he served in that office from 1940-1945 and again from 1951-1955. His speeches, especially his wartime broadcasts, inspired a nation under German bombardment and are considered among the most powerful ever delivered in the English language.

So, a compilation of his correspondence promises to be a cornucopia of insights into the man who once introduced himself by saying, “We are all worms, but I do believe I am a glow worm.” The letters he wrote as a child to his mother, his nanny, and his stern father reveal young Winston to be stubborn, willful, and rebellious but utterly persuasive in getting his way — characteristics that would define him as a world leader.

At the age of 13, the adolescent wanted nothing more than to be sprung from boarding school in Brighton to return to London for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. Young Winston wrote home that he particularly longed to see “Buffalow [sic] Bill,” the Wild West show of William F. Cody. His teacher denied his request to be excused, so he drafted a letter for his mother, Lady Randolph (Jennie Spencer Churchill), to sign in order to release him from school.

“My dear Mamma,” he wrote without punctuation, “I shall be very disappointed, disappointed is not the word I shall be miserable, after you have promised me, and all, I shall never trust your promises again. But I know that Mummy loves her Winny much too much for that. Write to Mrs. [sic] Thomson and say that you have promised me and you want to have me home…I am quite well but in a ferment about coming home it would upset me entirely if you were to stop me.” He closed by signing: “Love & kisses I remain yours as ever Loving Son (Remember) Winny.”

The next day, “Winny” wrote another letter, again entreating his mother: “Please, as you love me, do as I have begged you.” Not surprisingly, “dear Mamma” agreed.

As fascinating as the letters in this book are the photographs, particularly the one showing 7-year-old Winston in a sailor suit, plucky and cocksure, with one hand on his hip and the other resting on an ornate chair. He looks directly at the camera as if to say, My presence is your privilege.

cocksure, with one hand on his hip and the other resting on an ornate chair. He looks directly at the camera as if to say, My presence is your privilege.

Interestingly, one of the most iconic Churchill photographs is not included here, although the photographer, Yousef Karsh, was Canadian and considered a British subject in 1941 when he took his famous photo during the prime minister’s wartime visit to Ottawa. Karsh was allowed only two minutes, and as he rushed to set up, his subject lit up. He asked Churchill to put down his cigar because the smoke interfered with the film, but Churchill refused. So, moments before Karsh snapped his lens, he grabbed the cigar out of the great man’s mouth.

“By the time I got back to the camera,” he recalled, “he looked so belligerent he could have devoured me.” Yet when Churchill later saw the forceful image, he complimented the photographer, “You can even make a roaring lion stand still to be photographed.”

This book of letters will find its audience within the International Churchill Society (which offers annual memberships for $100), as well as at the National Churchill Library and Center at George Washington University in Washington, DC, at Churchill College in Cambridge, at Churchill’s War Rooms in London, and at Churchill’s Chartwell estate in Kent. There and elsewhere, the lion still roars.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Kitty Kelley’s Endless Generosity

by Holly Smith

Bestselling biographer and all-around excellent literary citizen Kitty Kelley has done it again. Just a few months after her historic donation to Biographers International Organization, Kelley has now given $100,000 to the nonprofit Washington Independent Review of Books in furtherance of our mission to share a love of reading freely and widely, to support full access to books of all kinds, and to introduce readers to authors they might not otherwise meet.

Bestselling biographer and all-around excellent literary citizen Kitty Kelley has done it again. Just a few months after her historic donation to Biographers International Organization, Kelley has now given $100,000 to the nonprofit Washington Independent Review of Books in furtherance of our mission to share a love of reading freely and widely, to support full access to books of all kinds, and to introduce readers to authors they might not otherwise meet.

“Kitty’s is the largest single gift the Independent has ever received, and her generosity honors us beyond words,” says Jennifer Bort Yacovissi, president of the Independent’s board of directors, on which Kelley serves. “By providing a stable base for our current operations, Kitty has given us the gift of breathing room to successfully pursue both new programs and the long-term funding strategies that will carry us well into the future.”

Rather than viewing Kelley’s unrestricted gift as an excuse to ease up on our efforts to bring you the reviews, columns, Q&As, and other features you’ve come to expect, we see it as a challenge to be better, to work harder, and to earn the backing of additional like-minded readers who appreciate what we do.

“We hope Kitty’s belief and investment in our mission inspires others to follow her example,” says Yacovissi. In the meantime, we intend to use the funding we have to continue adding our voice to those championing books and reading — especially now, when so many forces have aligned to silence them.

Holly Smith is editor-in-chief of the Independent.

August Wilson

by Kitty Kelley

The celebrated playwright August Wilson (1945-2005) was born Frederick August Kittel Jr. to a Black mother and a white father who abandoned his wife and six children. The fourth child and namesake son was called Freddie, but when his father deserted the family, Freddie took his mother’s surname and became August Wilson. The fatherless child never discussed the scars of being abandoned, but the loss permeated his life’s work.

The celebrated playwright August Wilson (1945-2005) was born Frederick August Kittel Jr. to a Black mother and a white father who abandoned his wife and six children. The fourth child and namesake son was called Freddie, but when his father deserted the family, Freddie took his mother’s surname and became August Wilson. The fatherless child never discussed the scars of being abandoned, but the loss permeated his life’s work.

Wilson adored his mother, Daisy, and desperately sought her approval, but she wanted him to be a lawyer and remained unimpressed by his poetry or even his award-winning plays. “You be a writer when you get something on television,” she told him. The day his play “The Piano Player” aired on CBS’ Hallmark Hall of Fame, February 2, 1995, Wilson gazed up to heaven and thought, “Look, Ma. I did it.” Reflecting on his mother’s passing, the heartbroken son explained:

“It is only when you encounter a world that does not contain your mother that you begin to fully comprehend the idea of loss and the huge irrevocable absence that death occasions.”

Although biracial, Wilson identified as Black and resented any attempt to be defined otherwise. He became irate when Henry Louis Gates Jr. questioned his Blackness in the New Yorker by writing, “He neither looks nor sounds typically Black — had he the desire he could easily pass — and that makes him Black first and foremost by self-identification.” As a playwright, however, Wilson subscribed to the creed of W.E.B. Du Bois, who promoted the four fundamental principles of “real Negro theater”: 1) About us 2) By us 3) For us 4) Near us.

In each of the 10 plays that comprise the Pittsburgh Cycle, Wilson — hailed as “theater’s poet of Black America” — portrays the African-American experience in a different decade of the 20th century. They all opened on Broadway, two of them posthumously:

“Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” 1984

“Fences” 1987

“Joe Turner’s Come and Gone” 1988

“The Piano Lesson” 1990

“Two Trains Running” 1992

“Seven Guitars” 1996

“King Headley II” 2001

“Gem of the Ocean” 2004

“Radio Golf” 2007

“Jitney” 2017

Wilson insisted his plays be produced and performed only by Black artists and denounced “color-blind casting,” asserting that “Blacks have always, historically, been the custodians for America’s hope.” Yet as Patti Hartigan writes — gloriously — in August Wilson: A Life, the first major biography of the man, Wilson’s genius was singular and his work universal, winning him two Pulitzer Prizes and 29 Tony Awards.

While Hartigan, a former theater critic for the Boston Globe, genuflects to Wilson’s monumental talent, she does not spare him his faults. Hypersensitive to slights and given to explosive rages unleashed on waitresses or workmen below him in status, Wilson was an errant husband who married three times and took countless lovers. His first priority in life — above family and friends — was his work. “For him,” Hartigan states, “writing was a force necessary for survival.”

As a high-school dropout with an IQ of 143, young Wilson haunted the aisles of Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Library, where he was relegated to the “Negro section.” He spent hours reading Langston Hughes, Ralph Ellison, and Paul Laurence Dunbar. He described the neighborhood in which he grew up as “an amalgam of the unwanted,” filled with a mishmash of Greeks, Jews, Syrians, Italians, Irish, and Blacks, “each ethnic group seeking to cast off the vestiges of the old country, changing names, changing manners…bludgeoning the malleable parts of themselves. Melting into the pot. Becoming and defining what it means to be an American.”

While Wilson described himself as a “race man,” and all his characters are Black, their stories of pain and sorrow and joy and resentment resonate as shared human verities. “There are always and only two trains running,” he once said. “There is life and there is death. Each of us rides them both.”

Wilson believed that African Americans needed to keep their history alive and cherish their heritage — complete with all its ancestors and all its ghosts. Maintaining that Black culture is unique and worthy of celebration, he sought out Black directors and dramaturges who understood his mission: to celebrate the lives of ordinary Black people.

This was lost on Bill Moyers when he interviewed Wilson in 1988 for the PBS series A World of Ideas. Moyers claimed that Blacks in America needed to embrace the mores of the dominant white culture in order to succeed and suggested that Blacks ought to aspire to the kind of bland middle-class life depicted on The Cosby Show. Those familiar with Wilson’s hair-trigger temper expected him to lay into the obtuse host, but knowing he was on national television, Wilson remained calm and simply remarked that Cosby’s show “does not reflect Black America to my mind.”

Moyers further humiliated himself by asking, “Don’t you grow weary of thinking Black, writing Black, being asked questions about Blacks?” Again, Wilson responded with restraint:

“How could one grow weary of that? Whites don’t get tired of thinking white or being who they are. I’m just who I am. You never transcend who you are. Black is not limiting. There’s no idea in the world that is not contained by Black life. I could write forever about the black experience in America.”

When Cosby gave a speech castigating Black youth for “stealing Coca-Cola” and “getting shot in the back of the head over a piece of pound cake,” Wilson blasted him. “A billionaire attacking poor people for being poor,” he told Time Magazine. “Bill Cosby is a clown. What do you expect? I thought it was unfair of him.”

Hartigan mentions in her author’s note that she had to paraphrase many of Wilson’s intimate letters, early plays, and poems because his estate declined to authorize their use in this book. Still, thanks to prodigious research and significant interviews, including notes from the days she spent with Wilson in 2005 for a Boston Globe Magazine profile, she has crafted a spectacular biography of “a truth teller” whom she eloquently describes as “a griot who accurately depicted the ordinary lives of honorable people whose stories were ignored by the mainstream culture.”

As William Styron once wrote, “A great book should leave you with many experiences and slightly exhausted at the end. You live several lives while reading.” Patti Hartigan has written just such a book about an illustrious playwright.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Taking Things Hard

by Kitty Kelley

Success is said to be a bitch goddess who sprays splendor like a shooting star in the night sky. Many writers spend their lives chasing her, most to no avail. John Keats, Franz Kafka, Henry David Thoreau, Emily Dickinson, Herman Melville, Edgar Allan Poe — all died without ever experiencing her starshine.

Success is said to be a bitch goddess who sprays splendor like a shooting star in the night sky. Many writers spend their lives chasing her, most to no avail. John Keats, Franz Kafka, Henry David Thoreau, Emily Dickinson, Herman Melville, Edgar Allan Poe — all died without ever experiencing her starshine.

Not so F. Scott Fitzgerald. The goddess wrapped him in riches, recognition, and renown at the age of 24 with his first novel, This Side of Paradise. Two years later, in 1922, he published The Beautiful and the Damned, and she showered him with international fame and prestige. Fitzgerald became the trumpeter of the Roaring Twenties, an era of champagne wealth and flapper frivolity that lasted as long as a bubble before it burst and plunged the country into years of depression. The bitch goddess took flight just as the trumpeter was embarking on the novel that would eventually become his legacy. He would not live long enough to savor its rewards.

Fitzgerald’s life has been chronicled in numerous biographies, letters, essays, scrapbooks, memoirs, notebooks, documentaries, and films, a challenging cornucopia facing any modern-day author who aspires to examine the life that produced what many claim is the United States’ greatest novel. “If you want to know what America’s like, you read The Great Gatsby,” said Professor John Kuehl of New York University. “Fitzgerald is the quintessential American writer.”

Most scholars sniff at Fitzgerald’s short stories, but Robert R. Garnett, professor emeritus of English at Gettysburg College, has chosen to limn the writer’s life through some of those 180 tales in Taking Things Hard: The Trials of F. Scott Fitzgerald. The title springs from Fitzgerald’s assessment of himself as a scribe. In a letter to Ernest Hemingway, he wrote, “Taking things hard…That’s [the] stamp that goes into my books so that people can read it blind like brail.”

Hemingway agreed. “We are all bitched from the start, and you especially have to be hurt like hell before you can write seriously.”

Garnett concurs. “For Fitzgerald, the emotions of love and loss were far more compelling than any idea,” he writes. “[He] was not an intellectual.”

Starting with one of “the worst things F. Scott Fitzgerald ever wrote for publication,” Garnett pulls out a “deservedly unknown” 1935 short story published in Redbook, which he describes as “wooden, simplistic, puerile, awash in cliché and banality, with ninth-century colloquial rendered in a hodgepodge of cowboy-movie, hillbilly, and detective novel.” (Here, one is tempted to steer the professor to The Elements of Style, in which Strunk and White advise using nouns and verbs rather than adjectives and adverbs.)

The year 1935 is crucial to Garnett’s book — and to Fitzgerald’s life — because it marks “the crack-up,” when the magic had drained from the writer’s golden world and everything turned to dross. He was institutionalized for alcoholism, and his descent was chronicled in a 150-page, single-spaced journal that Garnett feels “is the most valuable single source for any period of his life.” The journal was written by Laura Guthrie, who met Fitzgerald when both were recuperating in Ashville, North Carolina. During that time, she became his confidant, advisor, and crying towel.

Fitzgerald later wrote three Esquire articles about his “crack-up,” which one biographer described as “sheer brilliance.” Garnett dismisses this as sheer nonsense. “Far from brilliantly written, the articles are littered with the cliches and tired metaphors of slipshod writing — ‘the dead hand of the past,’ ‘up to the hilt,’ ‘a place in the sun,’ ‘not a pretty picture,’ ‘burning the candle at both ends,’ ‘sleight of hand,” and ‘beady-eyed men.’” Garnett further fillets Fitzgerald’s series as “filled with vagueness, obscurity, facile generalizing, non sequiturs, and padding (a random diatribe against Hollywood, for example).”

Tinseltown was hell for Fitzgerald, who’d moved there in 1937, hoping to resuscitate his career and recapture vanished glory. Still married to Zelda, at the time institutionalized with schizophrenia, he moved in with Sheilah Graham, the nationally syndicated Hollywood gossip columnist, and lived with her until he died of a heart attack in 1940.

On the subject of Graham, Garnett sounds a bit puritanical, alluding to her “amorous past” and dismissing her as “ambitious, enterprising, attractive, hardworking, shrewd, and not over-scrupulous, she had climbed from…poverty to become a chorus girl, then journalist.” The professor judges her as “too conventional, vin ordinaire, to generate much emotion [from Fitzgerald] beyond comfort and gratitude.”

How interesting it might’ve been for an accomplished scholar such as Garnett to have examined Graham and her ascent in the world in comparison to that of Jay Gatsby in Fitzgerald’s masterpiece. Both working-class characters of questionable backgrounds and no education came to represent the American Dream. An analysis of such by an English professor could’ve added insight and scholarship to the corpus of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Alas, a missed opportunity.

Chances are, the bitch goddess will not be spraying splendor on Garnett’s treatise, but the professor can take comfort in the legion of Fitzgerald aficionados who will find some nuggets within Taking Things Hard to be worthy of gold.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

BIO Award Winner Kitty Kelley’s Speech

Kitty Kelley won the 2023 Biographers International Organization Award. On Saturday, May 20, at the 2023 BIO Conference, it was also announced that Kelley will make a gift of $1 million to BIO, to be given over the course of five years. You can read more about that here.

The following is Kitty’s keynote address:

If I get run over tonight, please make sure that this BIO award leads my obit, because it’ll be the only time that my name shares the same space with Ron Chernow and Robert Caro and Stacy Schiff. But I don’t want to think about obituaries right now. I want to share with you a little bit about the writing life that brings me here today.

I love books and as much as I enjoy fiction, I bend my knee to nonfiction, particularly biography—the art of telling a life story. All kinds of life stories—memoir, authorized and unauthorized biography, historical narrative, or contemporary profiles.

In the last few decades, I’ve written biographies about living icons, a genre that is sometimes dismissed as “unauthorized biography” and, unfortunately, the term is sometimes said as if you’re emptying a bedpan or cleaning up the dog’s mess. Unauthorized biographies are not approved by everyone and rarely appreciated by their subjects. One exception, of course, is the New Testament, which was written by disciples who never knew their subject.

About 40 years ago, I thought I’d died and gone to biography heaven when Bantam Books offered me a grand advance to write the unauthorized biography of Frank Sinatra. I’d written two previous biographies and been robbed on both. On the first one, I didn’t have an agent—which is like driving a car without a steering wheel. On the second, I had an agent straight out of Oliver Twist. You may remember the woman who advised Linda Tripp to advise Monica Lewinsky to save her blue dress. Well, that same woman was once a literary agent who caused about $70,000 in foreign sales to go missing on my Elizabeth Taylor biography. My lawyer was incensed and insisted I sue. I told him to write the agent, say I’d misplaced records, and ask for another accounting. I figured that way she could correct herself and repay the missing monies.

I’m embarrassed to admit that I let this go on for over a year because I just couldn’t believe a literary agent would steal from a client. My lawyer said, “Try to get it into your fat head: She’s not Max Perkins. She’s Ma Barker.”

After 17 months, I finally filed suit. Depositions were taken and the case went to federal court in Washington, D.C. I fully expected her to settle because the evidence was so overwhelming. Instead, the case went to trial and the jury found Ma Barker guilty on all six counts, including fraud. They demanded she make payment on the courthouse steps and even asked for punitive damages.

I suppose the lawsuit was a great victory, because I unloaded a bad agent and got a good one, but I was in no hurry to do another biography. I’d just learned the hard way that there’s no education in the second kick of a mule. I’d undertaken the Elizabeth Taylor biography, hoping to write about the Hollywood studio system that had shaped our fantasies for most of the 20th century. I envisioned weaving that theme into the life story of Elizabeth Taylor, who grew up as a little girl at MGM, and went to school at MGM and . . . married many MGM men. But my plan for this historical narrative soon got buried in Ms. Taylor’s Technicolor life of husbands and hospitals and jewelry stores.

My agent asked, if I were to consider writing another life story, who would be of interest? I said, “Well, the gold ring on the merry-go-round would be Frank Sinatra, because no one’s really done it, and he epitomizes the American dream.” She agreed and that was the end of the subject until a couple weeks later when she called and said she had a generous offer from Bantam Books.

Soon I was back in the biography business, thinking I’d paid my hard luck dues. I’d had a bandit publisher on my first book and a thieving agent on my second. Now was third time lucky. And for a few weeks it was . . . until I was served a subpoena from Frank Sinatra, announcing that he was suing me for $2 million dollars for usurping the rights to his life story. He claimed that he and he alone (or someone he authorized) was entitled to write his life story, and I certainly had not been authorized.

I immediately called my publisher, and Bantam’s legal counsel informed me that I was on my own. “Mr. Sinatra has not sued us,” she said. “He’s sued you, and since you’ve not given us a manuscript, we’re not involved. So, I’d advise you to get legal counsel in California, which is where you’ve been sued and do keep us informed.”

“But I haven’t written a word. I’ve only just begun. My manuscript is years away.”

“We’ll talk then,” she said, before hanging up.

Now, getting sued by a billionaire with Mafia ties concentrates the mind, especially after your publisher leaves the scene. I called my friend, the president of Washington Independent Writers, to commiserate. “I wish we could help you, Kitty, but we’re almost broke,” she said. I assured her that I wasn’t looking for money—just moral support. “Well, in that case, let me get on the horn.” She contacted several writers’ groups, including the Authors Guild and PEN and the American Society of Journalists and Authors, and Sigma Delta Chi, and the National Writers Union. Days later, they held a press conference at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., to denounce Sinatra for using his power and influence to intimidate a writer before she’d written a word. They denounced his lawsuit and his assault on the First Amendment. As journalists, they understood what was at stake if Sinatra prevailed.

I retained the law firm of O’Melveny and Myers in Los Angeles and tried to keep working on the book, but was interrupted a few weeks later when I was in New York doing interviews and my lawyer called to tell me to get back to D.C. because the LA lawyers were coming to Washington for a meeting that would also be attended by my publisher. The LA lawyers said they’d received a tape recording from Sinatra’s lawyers of me supposedly misrepresenting myself as Sinatra’s authorized biographer, and this tape recording was the proof that they were going to present in court.

Now I was scared, even though I knew I hadn’t made such a telephone call. But I began to second-guess myself, wondering if maybe under the pressure I’d snapped my cap. By the time the lawyers arrived that Monday morning I was ready for handcuffs.

Three teams of lawyers sat down in my living room and put the tape in the recorder. No one said a word for the first two minutes because what we heard sounded like Porky Pig flying high on helium. In a squeaky voice, Porky said he was me and Frank Sinatra told me to call for an interview. The lawyers played that tape three times and we all listened to Porky Pig again and again before anyone said a word. Then all the lawyers laughed, clearly relieved, knowing the tape was a phony. I didn’t laugh.

“This lawsuit has gone on for almost a year and now someone is willing to lie under oath to say that I misrepresented myself to get an interview.”

“Don’t worry. We’ll send this to the tape labs at U.S.C., they’ll send the report to Sinatra’s team, and we’ll file for a dismissal. Meantime, just tape all your interviews.”

I tried to explain to the lawyers that you couldn’t always tape interviews, especially in the early 1980’s, when the technology wasn’t sophisticated. Taping in restaurants was difficult over the clinking of glasses, and taping phone interviews wasn’t legal in every state, even with two-party permission.

I finally decided that the best way to protect myself was to write a thank-you note to everyone I interviewed. That turned out to be 800 notes. They were polite and also protective. I’d thank them for the time they gave me in their home or their office or their favorite bar—wherever we’d done the interview; I’d compliment them on the polka dot bow tie they wore or the pretty pink blouse or their red tennis shoes; I’d mention the fabulous décor, or a particular piece of art, or our great salad in such-and-such a restaurant—any detail that set the time or place. Then I’d send it off and keep a copy in my files, because three or four years later when the book was finally published, they might very well have forgotten that interview or, more likely, wish they had.

That happened with Frank Sinatra Jr. He’d agreed to be interviewed when he was performing in Washington, D.C. His representative asked if I’d be bringing a camera crew, and I said no crew, just a still photographer. Then I quickly called my friend Stanley Tretick, one of President Kennedy’s favorite photographers who had worked for UPI and then LOOK magazine.

Stanley and I arrived at the Capitol Hill Hilton in the afternoon and went to Sinatra’s suite. His publicist met us and then disappeared when Frank Jr. entered the room. Sinatra’s only son sat down and asked me to sit close to him because he didn’t want to strain his voice. He was performing that night. So, I moved over, notebook in hand. The first 30 minutes of the interview went well as Sinatra Jr. talked about accompanying his father on tour and hanging out in Vegas with his father’s friends. Then he leaned over and said, “Hon, I know what happened to Jimmy Hoffa.”

I didn’t move. Because no one knew what happened to Jimmy Hoffa. They knew he was dead, but they didn’t know how or by whom. And now the son of a mob-connected man was going to tell me.

For a split second I wondered what I should wear when I got the Pulitzer Prize.

Just as Frank Sinatra Jr. leaned over to whisper in my ear, Stanley dropped his camera bags on the floor, and said, “Well out with it, man. What the hell happened to Hoffa?”

Frank Sinatra Jr. reared back as if he’d been clubbed. He looked at me, then he bolted from his chair and ran into the bedroom, slamming the door. His publicist came running out and said we had to leave. I begged for more time, saying the interview wasn’t finished, but the publicist was physically pushing us out the door.

Up to that point, Stanley Tretick had been one of my closest friends. Now I looked at him as if he’d just been possessed by the Tasmanian devil.

“Aw, hell. He doesn’t know what happened to Jimmy Hoffa.”

“Really?” I said. “And since when are photographers clairvoyant? And what kind of a lunkhead photographer throws a hissy in the middle of a reporter’s interview? Did it ever occur to you that what the son of a mob-connected man has to say about the disappearance of Jimmy Hoffa might be of interest?”

By now I was down the steps and storming the street to hail a cab. I refused to ride in the same car with a crazy person when I was homicidal. I didn’t speak to Stanley for some time, but he became my best pal again when the Sinatra biography was published. By then Frank Sinatra had dropped his lawsuit but his son now decided to sue, denying he’d ever given me an interview. His lawyers contacted my publisher and everyone braced for another lawsuit. But Stanley produced one of the photos he’d taken during our interview that showed me sitting next to Frank Sinatra Jr. with a notebook in [my] hand and a tape recorder on the table.

That photograph certainly trumped all of my little thank-you notes. Yet I can’t tell you how many times those notes saved me. When I wrote the Nancy Reagan biography, letters rained down on Simon & Schuster from corporate tycoons and all manner of political operatives, who took offense with the words attributed to them or to their wives or secretaries or associates, and at the bottom of every letter was a “cc” to President Ronald Reagan. Each time the publisher’s lawyer would call me to go over my notes and my tapes, and then he’d send a courteous reply, saying the publisher stands by the book and its accuracy.

At first, I wanted the publisher to “cc: President Reagan” just like all the letter writers had done, but the lawyer said no reason to stir the beast. “Those are weasel letters. They’re sent simply to show the flag.” He was right, and there were no retractions and no lawsuits.

That controversial biography became the cover of Time, Newsweek, People, Entertainment Weekly, and The Columbia Journalism Review, and [was] presented on the front pages of The New York Times, The New York Post, and the New York Daily News.

On the day of publication, President and Mrs. Reagan held a press conference to denounce the book, saying that I had—quote—“clearly exceeded the bounds of decency.” And three days later, President Richard Nixon agreed. President Nixon wrote a letter to President Reagan to commiserate. President Reagan responded, saying that everyone he knew had denied talking to the author. Reagan even named the minister of his church, who’d been cited as a source, and the minister had written a denial to all his parishioners in the Bel Air Presbyterian Church bulletin.

Now, I really tried not to respond to every accusation, but this one from a man of the cloth got to me, and I wrote to remind him of the 45 minute interview he’d given in his office. I enclosed a transcript of his taped remarks and asked him to please send around another church bulletin—with a correction. Of course, he didn’t, which proves the wisdom of Winston Churchill, who said that a lie flies halfway around the world before the truth gets its pants on.

Having rankled President Reagan and President Nixon, I later rattled President George Herbert Walker Bush. I’d written to him as a matter of courtesy, when I was under contract to Doubleday to write a historical retrospective of the Bush family, and said I’d appreciate an interview sometime at his convenience.

President Bush never responded to me but he directed his aide to write my publisher, saying:

“President Bush has asked me to say that he and his family are not going to cooperate with this book because the author wrote a book about Nancy Reagan that made Mrs. Reagan unhappy.” First Lady Barbara Bush had been so incensed when she saw my books displayed in the First Ladies Exhibit at the Smithsonian that she directed the curator to remove the display, which he did the next day. In fact, I might not have known about it had I not taken my niece to the Smithsonian a few weeks before and we’d seen the display and took a picture of it.

That photograph now hangs in my guest bathroom next to autographed cartoons from Jules Feiffer and Garry Trudeau. Over the years, that loo has become crowded with cartoons from all of my various books. My sister was very impressed when she saw them. She said to my husband, “I think it’s great that Kitty has put up all the bad ones.” My husband said, “There were no good ones.”

My biography on the Bush family dynasty was published in 2004, in the midst of a contentious presidential campaign. Bush Jr. was running for a second term, and I was lambasted by his White House press secretary, the White House deputy press secretary, the White House communications director, the Republican National Committee, and the house majority leader, Tom DeLay. Mr. DeLay even wrote a colorful letter to my publisher, saying that I was—quote—“in the advanced stage of a pathological career” and the publisher was in—quote—“moral collapse for publishing such a scandalous enterprise.”

When the Bush book became number one on the New York Times bestseller list, I was dropped from the masthead of The Washingtonian Magazine, where I’d been a contributing editor for 30 years. The new owner of the magazine was a Bush presidential appointee. The editor told me, “Your book was too personal. Too revealing.”

“But that’s what a biography is,” I said. “It’s an intimate examination of a person in his times, and in this case a powerful person in the public arena. The President of the United States influences our society, with actions that affect our lives.”

I quoted the actor Melvyn Douglas from the movie Hud. He talked about the mesmerizing power of a public image: “Little by little the look of the country changes because of the men we admire.” And Colum McCann, in his novel Let the Great World Spin, wrote: “Repeated lies become history, but they don’t necessarily become the truth.”

This is why biography is so vital to a healthy society. Whether authorized or unauthorized, biography presents a life story—sometimes it’s an x-ray of a manufactured image, sometimes it’s a gauzy bandage. The best biographers try to penetrate dross and drill for gold. As President Kennedy said, “The great enemy of the truth is very often not the lie—deliberate, contrived and dishonest—but the myth, persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic.”

I do not relish living in a world where information is authorized, sanitized, and homogenized. I read banned books. I applaud whistleblowers and I reject any suppression by church or state. To me, the unauthorized biography, which requires a combination of scholarly research and investigative reporting, is best directed at those figures still alive and able to defend themselves, who exercise power over our lives. . . . I firmly believe that unauthorized biography can be a public service and a boon to history.

The most solid support I’ve received over the years has come from writers—journalists and historians and biographers—who believe in the First Amendment. Who champion the public’s right to know.

These are principles that feed my soul and fill my heart, which is why I’m so grateful to be honored by you today with this award.

Thank you.

King: A Life

by Kitty Kelley

They said one to another

Behold here cometh the Dreamer

Let us slay him

And we shall see what will become of his dreams.

– Genesis 37:19-20

These words are carved into the cement plaque that rests outside room 306 of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. They mark the place where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. The dreamer’s death transformed his murder site into a shrine that now houses the National Civil Rights Museum, where King’s life continues to inspire, drawing thousands of visitors every year.

These words are carved into the cement plaque that rests outside room 306 of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. They mark the place where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. The dreamer’s death transformed his murder site into a shrine that now houses the National Civil Rights Museum, where King’s life continues to inspire, drawing thousands of visitors every year.

Scholars and historians have long explored the legacy of the Baptist minister from Georgia who preached a gospel of nonviolence. Deservedly, many King biographies have won prestigious prizes, among them Taylor Branch’s magisterial trilogy: Parting the Waters, Pillar of Fire, and At Canaan’s Edge. Additional tributes to King include I May Not Get There with You by Michael Eric Dyson; Bearing the Cross by David J. Garrow; Let the Trumpet Sound by Stephen B. Oates; Death of a King by Tavis Smiley; The Promise and the Dream by David Margolick; and The Sword and the Shield by Peniel E. Joseph.

Now comes Jonathan Eig with King: A Life, which promises “to recover the real man from the gray mist of hagiography.” Regrettably, says the author, “In the process of canonizing King, we’ve defanged him…[but] King was a man, not a saint, not a symbol.” In removing the mantle, Eig presents here an orator of soaring rhetoric who unapologetically plagiarized his speeches, saying his goal was to move audiences. Even King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech seems to have had its origins in Langston Hughes’ poems “I Dream a World” and “Dream Deferred.”

Misappropriating others’ work is a grievous sin for scholars, a “bad habit,” Eig writes, that King started in high school and continued as a graduate student at Crozier and later at Boston University, where he earned his Ph.D. with a dissertation that contained more than 50 sentences lifted from someone else’s work. By contrast, readers will note how generous Eig is to his own sources, giving previous biographers their due and quoting many by name in his text, not simply relegating them to chapter notes in the back of the book. Just as noteworthy is Eig’s appreciation for all who contributed to King: A Life; he lists each name under “Acknowledgements: Beloved Community.”

In this biography, his sixth book, Eig writes like an Olympic diver who jackknifes off the high board, slicing the water without a ripple. He performs with sheer artistry, like Picasso paints and Astaire dances. In unspooling the life of King, Eig presents a complicated man who attempted suicide twice; who was plagued by clinical depression so deep it required hospitalization; who chewed his nails; and who gave up the “true love” of his life, a white woman named Betty Moitz, because he realized, with her, he would never be accepted as a preacher in Black churches. The late Harry Belafonte, who himself married a white woman, told Eig that King never stopped talking about Moitz, and King’s mentor in graduate school described him after the break-up as “a man with a broken heart,” adding, “he never recovered.”

Although he married Coretta Scott and had four children with her, King pursued many women throughout his life. While Eig is unsparing about those extramarital affairs, he writes gently: “King’s busy schedule of travel also afforded him opportunities to spend time with women other than Coretta.”

The author also draws interesting similarities between King and John F. Kennedy, both of whom indelibly marked their era:

- Both were influenced by powerful (and philandering) fathers.

- Both enjoyed a privileged lifestyle above their contemporaries.

- Both were accused of plagiarism.

- Both experienced discrimination (JFK as an Irish Catholic; King as a Black man).

- Both excelled as public speakers.

- Both were assassinated.

King was particularly threatened by the never-made-public tape recordings FBI director J. Edgar Hoover ordered, turning federal agents into bloodhounds and instructing them to install bugs wherever King traveled. Hoover distributed copies of the recordings, which contained evidence of “unnatural sexual acts,” to President Lyndon Johnson, White House officials, and journalists in order to undermine King’s credibility. To further ensure his ruin, Hoover met with a group of woman journalists and declared King the country’s “most notorious liar.”

King reportedly wept over the slur to his life’s work but managed a masterful response to the press:

“I cannot conceive of Mr. Hoover making a statement like this without being under extreme pressure. He has apparently faltered under the awesome burden, complexities and responsibilities of his office. Therefore, I cannot engage in a public debate with him. I have nothing but sympathy for this man who has served his country well.”

By opposing the “immoral” war in Vietnam, King, who’d received the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, drew the unremitting ire of Johnson. As Eig writes, King’s “conscience would not allow him to cooperate with an advocate and purveyor of war.” Infuriated, Johnson never forgave the man who’d given his presidency its three greatest legislative achievements: the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

While Eig reveals the flawed man behind the myth, Martin Luther King Jr. still stands tall and strong enough to shoulder Shakespeare’s words from “Measure for Measure”:

They say best men are molded out of faults,

And, for the most, become much more the better

For being a little bad

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

(Color photo of Martin Luther King Jr. by Stanley Tretick, 1966, from Let Freedom Ring.)

Kitty Kelley Wins 2023 BIO Award

Kitty Kelley has won the 14th BIO Award, bestowed annually by the Biographers International Organization to a distinguished colleague who has made major contributions to the advancement of the art and craft of biography.

Widely regarded as the foremost expert and author of unauthorized biography, Kelley has displayed courage and deftness in writing unvarnished accounts of some of the most powerful figures in politics, media, and popular culture. Of her art and craft, Kelley said, in American Scholar, “I do not relish living in a world where information is authorized, sanitized, and homogenized. I read banned books, I applaud whistleblowers, and I reject any suppression by church or state. To me, the unauthorized biography, which requires a combination of scholarly research and investigative reporting, is best directed at those figures still alive and able to defend themselves, who exercise power over our lives. . . . I firmly believe that unauthorized biography can be a public service and a boon to history.”

Among other awards, Kelley was the recipient of: the 2005 PEN Oakland/Gary Webb Anti-Censorship Award; the 2014 Founders’ Award for Career Achievement, given by the American Society of Journalists and Authors; and, in 2016, a Lifetime Achievement Award, given by The Washington Independent Review of Books. Her impressive list of lectures and presentations includes: leading a winning debate team in 1993, at the University of Oxford, under the premise “This House Believes That Men Are Still More Equal Than Women;” and, in 1998, a lecture at the Harvard Kennedy School for Government on the subject “Public Figures: Are Their Private Lives Fair Game for the Press?” In addition, Kelley was named by Vanity Fair to its Hall of Fame as part of the “Media Decade” and she has been a New York Times bestseller multiple times.

For over 30 years, Kelley has been a full-time freelance writer. In addition to the American Scholar, her writing has appeared in The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Newsweek, Ladies’ Home Journal, The Chicago Tribune, The Washington Times, The New Republic, and McCall’s. She is also a frequent contributor to The Washington Independent Review of Books.

Heather Clark, chair of the BIO Awards Committee, said: “The Awards committee is thrilled to recognize Kitty Kelley for her outstanding contributions to biography over nearly six decades. We admire her courage in speaking truth to power, and her determination to forge ahead with the story in the face of opposition from the powerful figures she holds accountable. The committee would also like to recognize Kitty’s many years of service to BIO, especially her fundraising prowess and commitment to growing BIO’s membership ranks. Kitty is a force of nature and a deeply inspiring figure who deserves the highest recognition from BIO for her contributions to advancing the art and craft of biography.”

Of her award, Kelley said, “I’m dazzled by the BIO honor and feel like Cinderella when the glass slipper fit. Please don’t wake me up from this dream.”

Previous BIO Award winners are Megan Marshall, David Levering Lewis, Hermione Lee, James McGrath Morris, Richard Holmes, Candice Millard, Claire Tomalin, Taylor Branch, Stacy Schiff, Ron Chernow, Arnold Rampersad, Robert Caro, and Jean Strouse.

Kelley will give the keynote address at the 2023 BIO Conference, on Saturday, May 20.

2023 BIO Award Winner Kitty Kelley interviewed by Heath Hardage Lee, March 28, 2023

Master Slave Husband Wife

by Kitty Kelley

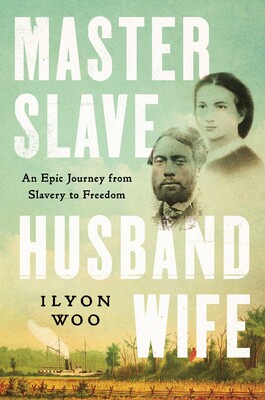

The morning after Martin Luther King Day 2023 marked the release of Ilyon Woo’s extraordinary Master Slave Husband Wife: An Epic Journey from Slavery to Freedom. Reviewers received advance proofs from the publisher with a note from Bob Bender, executive editor of Simon & Schuster, extolling the book and wondering why the story of Ellen and William Craft was not yet a staple of American history.

The morning after Martin Luther King Day 2023 marked the release of Ilyon Woo’s extraordinary Master Slave Husband Wife: An Epic Journey from Slavery to Freedom. Reviewers received advance proofs from the publisher with a note from Bob Bender, executive editor of Simon & Schuster, extolling the book and wondering why the story of Ellen and William Craft was not yet a staple of American history.

Soon, Mr. Bender. Soon.

The Crafts’ story is no ordinary slave narrative, although “ordinary” hardly describes the harrowing attempts that desperate human beings made in 18th- and 19th-century America to flee slavery’s choke-hold. Hordes of bounty hunters laid in wait to capture fugitives and drag them back to their owners in chains. Few made it to freedom, which is why the Crafts are so extraordinary: They took white supremacy and turned it upside down and sideways in order to escape in plain sight, executing one of the boldest feats of self-emancipation in U.S. history.

Ellen Craft was born to a white father, James Smith, who also enslaved Ellen’s 18-year-old mother. Smith’s wife gave Ellen — a living, daily reminder of her husband’s infidelity — as a wedding present to their daughter, Eliza, when she married Robert Collins of Macon, Georgia. Being half-sisters, the girls had grown up together, and Ellen, looking as white as Eliza, was trusted as a “house slave” to sew and cook and take care of the children. While in Macon, Ellen fell in love with William Craft, an enslaved man who lived nearby. Together, they schemed to run away at the end of 1848, more than a decade before the Civil War.

They plot every detail of their escape with strategic precision. Ellen, an expert seamstress, begins sewing the costume she will wear to disguise herself as a white man in failing health traveling to Philadelphia for medical treatment, accompanied by “his” slave. She makes baggy plus-fours — the stylish men’s trousers of the day — a white silk shirt, a black cravat, and a custom-designed jacket that only a gentleman of means could afford. Traveling as “Mr. Johnson,” she wears dark green glasses and a “double-story” black silk hat “befitting how high it rises, and the fiction it covers.”

She applies poultices to her face and wraps her right hand in bandages and a sling to explain why she can’t sign travel documents at several stops. (Being enslaved, Ellen was not allowed to learn how to read or write.) The dark-skinned William, acting like an obsequious slave, helps Ellen on and off trains and buses and boats, attending to “his” every need during their journey. At each stop, William ushers his infirm “master” to “his” first-class cabin before retiring to the colored quarters, where he eats from a slop bowl and sleeps standing up.

From Macon, the train rolls into Savannah, “City of Shade and Silence,” and site of the largest slave market in America, known as “the Weeping Time.” With staggering audaciousness, master and slave continue by steamship to Charleston, South Carolina, where, Woo writes:

“All along the harbor were tall ships and steamers, weighing the waves with their cargo; golden crops of rice, bales of cotton, chinoiserie — and chained below decks, the enslaved, a major commodity in this international port. There were slave sales near the docks, in shops, closer inland, and by the Custom House, which hosted the city’s largest open-air slave market on its north side, as Ellen knew. The sight was so disturbing to foreigners (and therefore bad for business) that, in a few years, the city would pass laws to hustle the trade indoors.”

Days later, the Crafts arrive in Richmond, Virginia, a veritable police state since Nat Turner’s Rebellion in 1831, still considered the most significant slave uprising in American history. “Mr. Johnson” and “his” slave rumble over Aquia Creek to Washington, DC, and through a dark channel to Fort McHenry in Baltimore, where Francis Scott Key, himself an enslaver, wrote “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Three more stops, and the couple finally cross the Mason-Dixon Line and reach Philadelphia, the so-called City of Brotherly Love, where even the Quakers drew lines to separate the “colored” benches in their meetinghouses.

Master Slave Husband Wife hits all the marks of a masterpiece: unforgettable characters, stirring conflicts, breathtaking courage, and a pulsating plot wrapped around an unforgiveable sin. Author Woo is a rare breed of writer — a scholar with a Ph.D. who’s nevertheless mastered the art of narrative nonfiction. She tells this story with incomparable skill, following the Crafts from Philadelphia to Boston, where they become icons of the abolitionist movement, traveling the antislavery lecture circuit. But the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 forces them to keep on the run. By law, they’re still enslaved and deeply in danger, especially once Robert Collins, Ellen’s owner back in Georgia, hires bounty hunters to track them down.

No longer safe in the U.S., the Crafts move to England for several years, where they bring up six children and publish an account of their escape, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom. When Abraham Lincoln signs the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, the Crafts feel safe enough to return home, first to South Carolina and then to Georgia, where they start a school and live out the remainder of their days.

Ellen and William Craft embody the human drive to relentlessly pursue freedom. Ilyon Woo, in Master Slave Husband Wife, honors their story with grace and humanity, and presents her publisher with a phenomenon.

Stand by, Mr. Bender. Stand by.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Shine

by Kitty Kelley

Tis the season, and January is the time for New Year’s resolutions. So, in that spirit, Larry Thompson, a Hollywood magnate, offers his book, SHINE: A Powerful 4-Step Plan for Becoming a Star in Anything You Do. Published in 2005, Thompson’s manual is an evergreen, he claims, and even more relevant for the new year of 2023. “If you’ll give me a few hours of your time,” he writes, “I will give you the knowledge to help you fulfill your dreams, and to rise and shine to meet your true destiny.” Snake oil sales pitch or road map to fulfilling dreams? You decide.

Tis the season, and January is the time for New Year’s resolutions. So, in that spirit, Larry Thompson, a Hollywood magnate, offers his book, SHINE: A Powerful 4-Step Plan for Becoming a Star in Anything You Do. Published in 2005, Thompson’s manual is an evergreen, he claims, and even more relevant for the new year of 2023. “If you’ll give me a few hours of your time,” he writes, “I will give you the knowledge to help you fulfill your dreams, and to rise and shine to meet your true destiny.” Snake oil sales pitch or road map to fulfilling dreams? You decide.

Thompson begins with his own story, growing up in Clarksdale, Mississippi, with a mother who urged him to leave home. “When you get educated,” Annie Thompson advised her son, “you’ve got to get out of this town ’cause [it’s] nothing but a graveyard with streetlights.” Like a stage mother (see the life stories of Gypsy Rose Lee, Shirley Temple, Elizabeth Taylor, Drew Barrymore, Brooke Shields, Dorothy Dandridge, Judy Garland, Groucho Marx), Larry Thompson’s mother pushed him. Pointing to the movie stars in Photoplay magazine, she said: “Now, they’re important. They have respect. I want you to go to Hollywood and be important like them.”

As further inspiration, Mama Thompson went to Memphis and bought a new dress, which she put in a box under her bed. “I’m saving that dress to wear when you invite me out to Hollywood to meet the Stars and to take me to the Academy Awards — on the night you win one.” Her dreams seeded his dreams. “I became driven,” he writes. “I developed the focus and the ambition and the high-level energy required to get there.”

Annie Thompson’s son left Mississippi at the age of 24 to live in California, where stars shine brightest. “Not only had I never been to California, but I had never met anyone who had ever been to California,” he recalls. Driving three days in a black Oldsmobile with maroon interior, Thompson arrived in Hollywood at 10 p.m. on a rainy night, exited the freeway onto Sunset Boulevard and reached the corner of Hollywood and Vine, where “I cried and cried and cried. I had arrived!”

Before beginning your ascent to stardom, Thompson recommends making a list of the great moments you’ve already had. He begins with his own, “The 150 Things I’ve done,” some of which are enviable, maddening and a couple gaspingly unbelievable:

No. 1: Sat on the deck of the Starship Enterprise with Captain Kirk.

No. 46: Made love in a royal balcony box at the La Scala Opera House in Milan.

No. 57: Witnessed the vision of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Medjugorje in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

No. 114: Helped President Gerald Ford become a mule. (Webster’s defines a mule as a cross between a donkey and a horse. The urban dictionary defines a mule as a carrier of things for someone else, usually illegal drugs. Thompson doesn’t explain.)

No. 140: Was ticketed on the way to Palm Springs doing 117 miles per hour in a Corniche.

No. 150: Became a multimillionaire along the way.

As you might expect of a Hollywood agent who’s managed the careers of “more than 200 stars,” there’s a heap of name-dropping: Elvis, Mama Cass, David Bowie, Peter Fonda, Tanya Tucker, Orson Welles, Drew Barrymore, Farrah Fawcett, Rene Russo, Mira Sorvino, Sylvester Stallone. You get the picture.

“Like wisdom and grace, Star quality is something you acquire,” Thompson writes. “A skill you can learn.” He defines and dissects the four elements of Stardom: Talent, Rage, Team, Luck, and provides a primer to each, complete with lists and exercises to do to become a Star. Using his own experience, he writes that Stardom is not an accident: “A drive will motivate you to move to L.A. or New York or Nashville. An Ambition will get you an agent. A passion will get you an acting job. A RAGE will make you a Star!”

Anyone who grows up feeling like an “outsider” or a “weirdo” has an edge. “There’s no one more likely to be a Star (Thompson always capitalizes Star) than someone who doesn’t fit in with the crowd.” Adversity helps. Growing up poor and impoverished in a broken family or learning to dodge bullets in New York’s Hell’s Kitchen ghetto, or being shuttled around foster homes with a begging bowl — each crippling experience bakes into the psyche the inspiration and resilience needed for Stardom.

Before beginning your ascent, the “Shine” meister advises: “Finding Your Team.” By this, he means deciding whether you’re a dog or a cat because you’re either one or the other. Cats, hard to get, are a bit mysterious with hidden agendas, and not totally forthcoming about anything and everything, and they let you get only so close. Dogs are uncomplicated. They adore you, they follow you. You tell them to sit, they sit. You tell them to heel, they heel.

Some in Thompson’s Star Kennel:

Star Dogs — Star Cats

George W. Bush — Bill Clinton

Jay Leno — David Letterman

Tom Hanks — Angelina Jolie

Billy Crystal — Warren Beatty

For some, Shine: A Powerful 4-Step Plan for Becoming a Star in Anything You Do might seem like a book of bromides — “Learn, Yearn, Burn, Discern.” “Dream Big” and “Don’t Give Up.” To others, it will become a bible that sits alongside Psycho-Cybernetics by Maxwell Maltz, M.D., who proved you can program your mind to achieve success and happiness, and Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way: A Spiritual Path to Higher Creativity.

Whether you’re a star dog or a star cat, the New Year of 2023 is yours to SHINE.

Originally published by The Georgetowner as an installment of “The Kitty Kelley Book Club”