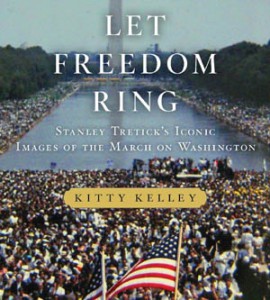

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

Bestselling author Kitty Kelley goes behind the lens of legendary Look photographer Stanley Tretick to capture a pivotal moment in our nation’s history: The March on Washington, August 28, 1963. Most of these extraordinary photos have never been seen before.

Bestselling author Kitty Kelley goes behind the lens of legendary Look photographer Stanley Tretick to capture a pivotal moment in our nation’s history: The March on Washington, August 28, 1963. Most of these extraordinary photos have never been seen before.

Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington will be published by Thomas Dunne Books in August 2013 in hardcover and ebook formats.

Preorder: Amazon Barnes & Noble Books-A-Million Apple IndieBound

Obama and the Legacy of Camelot

by Kitty Kelley

When Caroline Kennedy endorsed Barak Obama in 2008 as her father’s rightful heir she laid upon him the mantle of Camelot, and the enduring mystique of John F. Kennedy, who, according to polls, continues to be America’s most beloved president. Comparisons between the 35th and 44th presidents have been inevitable, and while there are striking similarities between the two men, there are also distinguishing differences.

Both rose to the nation’s highest office as junior U.S. Senators with scant legislative achievements to their credit. The man from Massachusetts served three terms in the House of Representatives before he won his Senate seat in 1952 and began campaigning for national office, running for Vice President in 1956 and for President in 1960. Obama, a state legislator in Illinois for seven years, began his run for the White House shortly after being elected to the Senate. Both men broke the barriers of bigotry to reach the highest office in the land–Kennedy as the first Roman Catholic; Obama as the first African American.

Erudite Ivy Leaguers, each seemed blessed with the gift of prose. Kennedy wrote three books, and won a Pulitzer Prize for Profiles in Courage; Obama made millions writing his best-selling memoir, Dreams from My Father. As a Boston scion and Harvard graduate, JFK. always smarted at being rejected for a seat on the Harvard Board of Overseers; Obama left Harvard with the distinction of having been the first person of color to be elected president of the Harvard Law Review.

Both men possessed extraordinary talents for oratory and inspired their generations with the poetry of hope–“the thing,” Emily Dickinson described, “with feathers that perches in the soul.” Their messages resounded for a nation grown restless after eight years of a Republican administration. Each man came to the presidency with their party in control of Congress, and each used that power to effect sweeping change. Kennedy introduced the most comprehensive and far-reaching civil rights bill, which was not passed on his watch, but became law under his successor. Obama signed the Affordable Care Act of 2010 which reformed health care to provide insurance for all Americans. Kennedy ordered federal departments and agencies to end discrimination against women in appointments and promotions; Obama signed the Lilly Ledbetter Act to provide fair pay in the work place. In addition, he succeeded in getting a measure passed to end discrimination against gays in the military.

Both men possessed extraordinary talents for oratory and inspired their generations with the poetry of hope–“the thing,” Emily Dickinson described, “with feathers that perches in the soul.” Their messages resounded for a nation grown restless after eight years of a Republican administration. Each man came to the presidency with their party in control of Congress, and each used that power to effect sweeping change. Kennedy introduced the most comprehensive and far-reaching civil rights bill, which was not passed on his watch, but became law under his successor. Obama signed the Affordable Care Act of 2010 which reformed health care to provide insurance for all Americans. Kennedy ordered federal departments and agencies to end discrimination against women in appointments and promotions; Obama signed the Lilly Ledbetter Act to provide fair pay in the work place. In addition, he succeeded in getting a measure passed to end discrimination against gays in the military.

Both Kennedy and Obama exuded a dash of glamour in their roles as Commander-in-Chief and became the darlings of Hollywood. As President, each brought to the White House a fashionable and accomplished First Lady, two adorable young children, and scene-stealing pets. Yet as beloved as each became, both men stirred ferocious passions and dangerous threats from extremists who accused them of treason.

As notable as their similarities are the differences which define and separate them. Kennedy grew up with immense wealth and the high expectations and powerful connections of his father, the former Ambassador to the Court of St. James, who was the 14th richest man in America in 1960, worth more than $400 million. Obama, a fatherless child, forged his way on the wings of a single working mother, who wandered the world and left her son to the loving care of her parents. As a young man he borrowed thousands of dollars to finance his education and was not able to repay his student loans until he was 43 years old.

Both elusive men, Kennedy and Obama cared mightily about their public image, not an insignificant concern for politicians. Kennedy, who worried about being portrayed as a rich man’s dilettante son, would not allow photographs inside Air Force One, saying it would look like a playboy’s luxury. Obama made sure cameras never caught him smoking cigarettes. Each understood the mesmerizing power of appearances and knew as the actor Melvyn Douglas says in the film Hud, “Little by little the look of the country changes just by looking at the men we admire.”

Both presidents tangled with corporate America and drew the ire of big business. Kennedy blasted the steel industry in 1962, saying their price increase was “unjustifiable and irresponsible.” Obama, a community organizer, championed the middle class, challenging Wall Street when he enacted financial regulatory reform, and demanded that the richest Americans to pay their full share of taxes.

Each had to find his way through military quagmires left by their predecessors. Kennedy was haunted by the Bay of Pigs invasion but carried the country through the Cuban Missile crisis. He later increased the number of US military advisers to South Vietnam to more than 16,000. Obama came to the White House determined to end the Iraq War which he did by December 2011. After sending 33,000 more U.S. soldiers to Afghanistan as part of a strategy to downsize the American commitment there, he vowed to end that war by 2014.

Politically, both men made judicious choices in their running mates, but Kennedy never gave Lyndon Baines Johnson the full partnership that Obama accorded to Joe Biden.

Kennedy left behind the Peace Corps, the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty and the promise of a man on the moon within the decade. Obama’s legacy must be left to the historians of tomorrow but at the dawn of his second term, following an inauguration that coincided with the fiftieth anniversary of President Kennedy’s last year in office, it is reassuring to believe that each man dedicated his presidency to setting the country’s course true north.

(Photo: President Barack Obama looks at a portrait of John F. Kennedy by Aaron Shikler, taken by official White House photographer Pete Souza)

Cross-posted from Huffington Post

The Patriarch

by Kitty Kelley

The Patriarch (Penguin Press) is the perfect title for the life story of Joseph Patrick Kennedy. It resounds with the drama of rolling drums to introduce a paterfamilias who created one of America’s most powerful political dynasties. The author, David Nasaw, was hand-picked by the Kennedys and given access to all the family’s personal papers, including the senior Kennedy’s letters, which comprise the ballast of this biography.

The Patriarch (Penguin Press) is the perfect title for the life story of Joseph Patrick Kennedy. It resounds with the drama of rolling drums to introduce a paterfamilias who created one of America’s most powerful political dynasties. The author, David Nasaw, was hand-picked by the Kennedys and given access to all the family’s personal papers, including the senior Kennedy’s letters, which comprise the ballast of this biography.

Such access is no surprise for an historian on the faculty of the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, where he is the Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. Distinguished Professor of American History. As President Kennedy’s in-house historian and the devoted biographer of Robert F. Kennedy, Schlesinger was no incidental contributor to the myths of Camelot, but this is not to say that Nasaw’s biography is hagiography. He covers the light as well as the dark corners of Joseph P. Kennedy’s complicated persona. But having written biographies of William Randolph Hearst and Andrew Carnegie, Nasaw prefers to describe himself “as an academic historian, not a biographer,” which may be why his narrative reads like an orange squeezed dry. For 896 pages he follows the chronology of Joseph P. Kennedy’s life (1888-1969) as methodically as a metronome, and documents all the facts with footnotes. Yet one wishes there had been a little more poet in the professor.

Joseph Patrick Kennedy was born to all the prosperity that East Boston allowed Irish-Catholics in the 19th-century, which was fathoms below the social acceptance accorded “proper Bostonians,” as Kennedy referred to his Protestant peers. Blessed with charm and intelligence, he was determined to break down the wall that separated former “bog-dwellers” from their Brahmin “betters.” This became his life’s ambition and drove him to make his son the country’s first Irish-Catholic president.

After attending Boston Latin, then the best public school in the country, young Joe was accepted at Harvard. There he excelled in athletics and networking, which, he impressed upon his sons in frequent letters, was the purpose of Harvard. “You will have a great start on any of your contemporaries and you should be able to keep up very important contacts,” he wrote. Befriending “the topmost people,” as he called them, became a lifetime priority.

After graduating from Harvard, Kennedy was unable to get a white-shoe job on Wall Street, so he became a bank examiner in Massachusetts and mastered the intricacies of an unregulated stock market, eventually earning a reputation as a “rapacious plunger.” He pounced on bankruptcies, foreclosures and receiverships, and used insider knowledge to buy and sell stock, all of which would later become illegal. As president of an East Boston bank he borrowed heavily from the bank to finance his trades, and borrowed even more to invest in commercial real estate. In 1945 he bought the Merchandise Mart in Chicago for $13 million. The family sold the Mart in 1998 for $630 million.

Kennedy also made huge profits from reorganizing and refinancing several Hollywood studios. During this time he managed the career of the film star Gloria Swanson, who became his mistress and traveled with him on his family vacations. A practicing Catholic, he also traveled with his own confessor. Nasaw reports that Kennedy spent little of his married life with his wife, Rose, who ignored his pursuit of other women just as her mother had done when her husband, Honey Fitz, the mayor of Boston, was caught with a cigarette girl named “Toodles.”

Making multimillions during the bull market of the 1920s, Kennedy had become one of the 14 richest men in America by 1957. By then he had established trust funds (each worth $90 million in 1960) for his nine children and each of their children. He provided his family with a luxe life of Rolls Royces, yachts, villas on the French Riviera, Hollywood mansions, an estate in Palm Beach, a summer compound in Cape Cod and a suite in the Carlyle Hotel.

In addition, Kennedy bought his own publicity machine. His legion of press agents included the respected New York Times columnist Arthur Krock, who was put on a secret annual retainer to do Kennedy’s bidding whenever he wanted positive coverage for himself or his family in the nation’s most influential newspaper.

Nasaw explores in detail Joseph Kennedy’s virulent anti-Semitism and his role as U.S. Ambassador to the Court of St. James when he aligned himself with Neville Chamberlain to appease Hitler. His isolationist views forced him to resign as ambassador and made him anathema to most Americans, but Kennedy never apologized. Even after the allied victory Kennedy told Winston Churchill that the war had not been worth the lives lost, including Kennedy’s first-born son and namesake, and the destroyed European economy.

Those familiar with Kennedy lore might be amused to learn that J.F.K. was considered by his father to be “the family’s problem child.” So concerned was Kennedy about his second son’s messy appearance, dilatory study habits and poor grades that he beseeched the headmaster at Choate to intervene and “do something about Jack.” Yet it was Joe Kennedy, not Rose, who cancelled vacations to stay home to nurse J.F.K. through many of his childhood illnesses.

What emerges from this biography is that the anti-Semitic, pro-Nazi, philandering wheeler-dealer was — first, last and always — a ferociously loving father who put his sons and daughters above all else. As he told President Roosevelt: “I did not want a position in the government unless it really meant some prestige to my family.”

Cross-posted from Washington Independent Review of Books.

Camelot

by Kitty Kelley

John F. Kennedy continues to reign as the most popular president of the twentieth century, according to recent Gallup polls. (Richard Nixon and George W. Bush remain the most unpopular). Most historians agree that Abraham Lincoln was the most important man to ever occupy the White House because he abolished slavery and kept the states united through a bloody civil war. Yet for most Americans, Kennedy, whose presidential accomplishments were slight, continues to glisten like a shamrock after a spring rain.

For those alive in 1963 this month casts a shadow of sadness as we recall where we were on November 22 when we heard about the president’s assassination. We remember the weekend binge of television coverage — the stalwart widow in her black veil, the riderless horse, the little boy’s salute to his father’s coffin and the eternal flame, which draws over 500,000 visitors a year to Arlington National Cemetery.

Beginning last year we mark the 50th anniversary of the Kennedy administration — the thousand days which J.F.K. defined as the New Frontier, a time when he said the torch was passed to a new generation. We were told to ask not what our country could do for us but what we could do for our country, and he showed us how by establishing the Peace Corps so Americans could do something positive and lasting. Since 1961 more than 210,000 volunteers have served in 139 countries.

Yet it is for something far less tangible that John F. Kennedy continues to be revered. Elected fifteen years after the end of WWII, he captured the spirit of those times. He radiated the excitement of change and the optimism of expectation. He broke the barriers of religious bigotry by becoming the first Catholic to be elected president, thereby making us believe that anything was possible, even sending a man to the moon and back within a decade. He moved further than his predecessors on civil rights by declaring that equality under the law was a moral issue “as old as the Scriptures and as clear as the Constitution.” He believed in horizons without limits. “No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings,” he said, speaking about the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty which was signed in August 1963.

Yet it is for something far less tangible that John F. Kennedy continues to be revered. Elected fifteen years after the end of WWII, he captured the spirit of those times. He radiated the excitement of change and the optimism of expectation. He broke the barriers of religious bigotry by becoming the first Catholic to be elected president, thereby making us believe that anything was possible, even sending a man to the moon and back within a decade. He moved further than his predecessors on civil rights by declaring that equality under the law was a moral issue “as old as the Scriptures and as clear as the Constitution.” He believed in horizons without limits. “No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings,” he said, speaking about the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty which was signed in August 1963.

John F. Kennedy brought style and charisma to the White House and a first family that captivated the country: a handsome, witty president, an elegant first lady, and two adorable young children. While his image was later tarnished by revelations of marital infidelity and reckless behavior, polls show that he still holds the public in thrall. Herbert Parmet, one of his many biographers, claimed he was nothing but glamour and gloss, and dismissed him as an “interim president who had promised but not performed.” Yet there is no way to diminish the nation’s nostalgia for this man who was felled in his prime, and became an enduring legend. No other president has left a larger footprint on his country than John F. Kennedy, who to date is honored by 149 institutions which carry his name — schools, hospitals, clinics, concert halls, arts centers and an international airport, proving perhaps that promise is as inspiring as performance.

John F. Kennedy brought style and charisma to the White House and a first family that captivated the country: a handsome, witty president, an elegant first lady, and two adorable young children. While his image was later tarnished by revelations of marital infidelity and reckless behavior, polls show that he still holds the public in thrall. Herbert Parmet, one of his many biographers, claimed he was nothing but glamour and gloss, and dismissed him as an “interim president who had promised but not performed.” Yet there is no way to diminish the nation’s nostalgia for this man who was felled in his prime, and became an enduring legend. No other president has left a larger footprint on his country than John F. Kennedy, who to date is honored by 149 institutions which carry his name — schools, hospitals, clinics, concert halls, arts centers and an international airport, proving perhaps that promise is as inspiring as performance.

Photos © Estate of Stanley Tretick, LLC, used with permission.

Cross-posted from Huffington Post

Capturing Camelot on Morning Express

Kitty Kelley appeared on HLN Morning Express to talk about Capturing Camelot on November 25, 2012.

Capturing Camelot on Starting Point

Kitty Kelley appeared on Starting Point on November 14, 2012 to talk about Capturing Camelot.

Capturing Camelot on Jansing & Co.

Kitty Kelley appeared on Jansing & Co. on November 14, 2012.

Capturing Camelot on the Today Show

Kitty Kelley appeared on the Today Show to talk about Capturing Camelot.

November 13, 2012

The Today Show also posted a slide show of photos from the book.

Review of American Lady

By Kitty Kelley

The jacket copy makes your mouth water with tantalizing promises of wealth, glamour and power. Even the title bespeaks upper-class gentility: American Lady: The Life of Susan Mary Alsop (Viking). This biography by Caroline de Margerie is the story of “the second lady of Camelot.” Many of us thought in the Kennedy administration that title belonged to the vice president’s wife, Lady Bird Johnson. While we’re never told who bestowed the honorific on Mrs. Alsop, we are assured that she is “an American aristocrat,” who “reigned over Georgetown society for four decades, her house a gathering place for everyone of importance, including John F. Kennedy, Katharine Graham and Robert McNamara.”

The jacket copy makes your mouth water with tantalizing promises of wealth, glamour and power. Even the title bespeaks upper-class gentility: American Lady: The Life of Susan Mary Alsop (Viking). This biography by Caroline de Margerie is the story of “the second lady of Camelot.” Many of us thought in the Kennedy administration that title belonged to the vice president’s wife, Lady Bird Johnson. While we’re never told who bestowed the honorific on Mrs. Alsop, we are assured that she is “an American aristocrat,” who “reigned over Georgetown society for four decades, her house a gathering place for everyone of importance, including John F. Kennedy, Katharine Graham and Robert McNamara.”

As someone who lives in Georgetown and enjoys reading about the myths of Camelot and American aristocrats, I could hardly wait to gobble up this book.

Perhaps the author, a member of the Conseil d’Etat, the highest administrative court in France, and once a diplomat, could not shake her silk stocking background long enough to probe beneath the surface. Or maybe she drew too close to Mrs. Alsop’s family, who gave her access to letters, papers and diaries that she barely quotes. Perhaps it was the author’s intercontinental collaboration with her sister, whom she credits with helping her complete the book. Then again, it might be the translation from French to English that makes this book (at 256 pages) read like biography lite.

“Slim” is the word de Margerie uses to describe Mrs. Alsop, an understatement for the stick-thin woman I met in Washington, D.C. (we went to the same Georgetown hairdresser). At 5’7” she was almost skeletal and appeared to weigh no more than 95 pounds, with blue-veined skin tissued over protruding bones. Even her son, William S. Patten, described his mother as “anorexic.” Yet her biographer chooses a polite characterization that is fathoms from the destructive disease of anorexia.

“Slim” seems to be the operative word for this book, whose euphemisms keep readers removed from knowing the woman whose life intersected with many charismatic figures of her era — Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, Greta Garbo, Noel Coward, Edith Wharton, Brooke Astor, Ho Chi Minh, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, and President and Mrs. John F. Kennedy.

Susan Mary Jay Patten Alsop (1918-2004) was the great-great-great-granddaughter of John Jay, one of the Founding Fathers, who signed the Treaty of Paris in 1783 and became the first chief justice of the United States. Born into a revered American family, she declared she saw “no future in being an ordinary person.” She didn’t even like associating with ordinary people. According to her biographer, “She had always preferred lords to cowboys.”

Born in Rome, Susan Mary, as she was called, grew up in South America, traveled in Europe, lived in Washington and New York, and summered in Maine. She graduated from the Foxcroft School, took a few courses at Barnard College and married at the age of 21 after meeting Bill Patten (Harvard, Class of 1932), nine years her senior. He was severely asthmatic, like her father, declared 4F and unfit for military service. So his mother-in-law, Mrs. Jay, got him hired by the U.S. State Department to work for Sumner Welles, undersecretary to Cordell Hull. Patten’s first assignment was Paris, where he and Susan Mary lived from 1945 to 1960, when he died of emphysema.

Susan Mary soon fell out of love with her “sickly but sweet” husband and became besotted with their close friend, Duff Cooper, the British ambassador to France (1890-1954), the great love of her life. Her biographer maintains that Bill Patten “never showed signs of torment or bother” over his wife’s affair, and Susan Mary “was convinced he did not know.” She gave birth to Cooper’s son in 1946 and kept the paternity secret from her husband. She finally told her son when he was 47 who his real father was.

Three months after Bill Patten Sr. died, his Harvard roommate, Joseph Alsop, proposed. A powerful (and pompous) political columnist, he was syndicated in over 300 newspapers. After the election of John F. Kennedy, Alsop decided he needed a hostess to entertain the president and first dady so he wrote to Susan Mary, saying they could become a part of history if she married him. He admitted he was homosexual, said he did not expect her to be in love with him and that she could take a lover at any time. Reckoning that her son and daughter needed a stepfather and she needed a place in Washington society, Susan Mary accepted. The marriage did not last, but their friendship endured to the end of their lives.

Following her separation from Alsop, she asked him for permission to continue using his name. At the age of 56 she became a writer and published her first book, To Marietta from Paris: 1945-1960, a compilation of her letters to her best friend, Marietta Peabody Fitzgerald Tree. She published three more books and then became a contributing editor to Architectural Digest for many years.

Toward the end of her life she was plagued by near blindness, drug addiction and alcoholism. She died at the age of 86 in the Georgetown house she had inherited from her mother. Her obituaries barely mentioned her career as a writer, celebrating her instead as a “socialite,” “hostess” and “Washington doyenne.” Most assuredly she would have been pleased by the social plaudits because her first priority as an American lady was maintaining her place in society. Readers accustomed to hearty biography will go away hungry from this little morsel, feeling deprived of the banquet promised on the book jacket.

Cross-posted from The Washington Independent Review of Books

Becoming an Independent Writer

Video of Kitty Kelley being interviewed by Stephen Hess, author of Whatever Happened to the Washington Reporters, 1978-2012:

http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/up-front/posts/2012/09/11-kitty-kelley-hess