Eunice: The Kennedy Who Changed the World

by Kitty Kelley

Eunice Kennedy Shriver longed to be Daddy’s little girl. “You are advising everyone else in that house on their careers, so why not me?” she wrote to her father. Joseph P. Kennedy did not ignore his daughter, but he directed his fiercest attention to his sons, determined to invest his millions in making one of them the first Irish Catholic president of the U.S. He accomplished his life goal in 1961 with the inauguration of John F. Kennedy.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver longed to be Daddy’s little girl. “You are advising everyone else in that house on their careers, so why not me?” she wrote to her father. Joseph P. Kennedy did not ignore his daughter, but he directed his fiercest attention to his sons, determined to invest his millions in making one of them the first Irish Catholic president of the U.S. He accomplished his life goal in 1961 with the inauguration of John F. Kennedy.

Still, “puny Eunie,” as her brothers called their gawky, skinny, sickly, big-toothed sister, refused to be ignored, and with determination and persistence, she finally forced her father’s admiration: “If that girl had been born with balls, she would have been a hell of a politician.”

Some might dispute any such lack as Eunice Kennedy Shriver barged into a man’s world and grabbed her rightful place alongside them, although she sometimes — but not always — considered them to be her betters.

She founded the Special Olympics, which spread to 50 countries, and because of her, those with physical and intellectual disabilities are no longer locked away. Society now educates them, employs them, and helps them thrive.

Eunice used her father’s vast connections and immense fortune to her best advantage. (She got admitted to Stanford because Joe Kennedy asked his friend Herbert Hoover to make it possible.) Through her father, she landed a job in the Justice Department as a special assistant to U.S. Attorney General Tom C. Clark. “Joe Kennedy had secured Eunice’s job the same way he had engineered a U.S. House seat for Jack,” McNamara writes, “with good connections and cold cash.”

During that time, Eunice and her brother Jack lived together in Georgetown, where they had an Irish cook and numerous friends, including Senator Joseph McCarthy and Congressman Richard M. Nixon of California. In her unpaid position, she developed interest and expertise in juvenile delinquency and appealed to her father for help in setting up a scholarship program.

Joe responded that the Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr. Foundation, established to honor his firstborn, killed in WWII, “would be glad to defray any expenses…in Boston.” Perceptively, McNamara notes “the random nature and mixed motives of the Kennedy Foundation’s early philanthropy. Solving social problems did not preclude advancing his children’s careers.”

Within a few years, Eunice commandeered the foundation and directed its resources into the field of mental retardation, perhaps in expiation for the plight of her sister Rosemary, the family’s special-needs child.

Recognizing Rosemary’s severe disabilities in London, when he was serving as U.S. ambassador, Joe Kennedy decided his daughter should undergo the experimental psychosurgery of a prefrontal lobotomy, which went horribly wrong, rendering Rosemary unable to function on her own.

Afraid that the stigma of mental retardation might affect the political ambitions he had for his sons, Kennedy sent Rosemary to be cared for by the Sisters of St. Francis of Assisi at St. Coletta School for Exceptional Children in Jefferson, Wisconsin. Her absence was not mentioned by her parents or her siblings for 30 years, until Eunice began “reintegrating her sister into the family that abandoned her.”

Like her mother, Eunice Kennedy Shriver was a zealous Catholic who accepted all the tenets of her church, including the sanctity of marriage and the abomination of abortion. Yet she turned a blind eye to the marital infidelities of her father and her brothers.

In 1980, when Gloria Swanson published an autobiography and revealed her long affair with Joe Kennedy, who took the Hollywood actress on family vacations with his wife and children, Eunice took umbrage. She fired off a blistering letter to the editor of the Washington Post, which McNamara does not mention. Extolling her mother as “a saint” and her father as “a great man,” Shriver lambasted Swanson’s revelation as “warmed-over, 50 year old gossip that accuses the dead [my father] and insults the living [my mother]…The closeness [my father] shared with my mother and her obvious devotion to him inspired his children to revere the values of home and family as well as public service and dedication to others.”

By that time, the sexual romping of the Kennedy men — father and sons — had become proven fact. The only marriage of Rose and Joe Kennedy’s nine children which still seemed intact was that of their fifth child, who adored the Blessed Virgin Mary and wanted to become a nun before she was persuaded, after a seven-year courtship, to marry R. Sargent Shriver.

That 1953 wedding was as grand as a coronation, with Francis Cardinal Spellman celebrating the nuptial Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, assisted by three bishops, four monsignors, and nine priests. The 32-year-old bride wore a white Christian Dior gown made in Paris, and 1,700 guests danced to a 15-piece orchestra on the Starlight Roof of the Waldorf Astoria.

But the wedding might not have occurred without the intervention of Theodore Hesburgh, the charismatic young priest from the University of Notre Dame who was prevailed upon by Joe Kennedy to persuade Eunice not to enter the convent, which Joe felt would be detrimental to JFK’s political career.

Because of Father Hesburgh’s high esteem for Sargent Shriver, he agreed to be Joe Kennedy’s heat-seeking missile, summoning Eunice for “a frank and honest exchange.” He told her that her vocation was not the convent but to marry Shriver, have his children, and continue the work she was doing with the mentally challenged.

He later told McNamara that Sarge “was the best, the very best of the bunch. I knew her not as well as I knew him, but she was a great gal. There are a lot of Kennedys. They come in all shapes and sizes. But who did the work she did? Who cared for Rosemary as she did? It took a lot of strength, I will tell you that. The men tend to outrank the women in that family, but she had as much or more to offer as any of them.”

Eileen McNamara writes with grace, elegance, and diplomacy, never making moral judgments on harsh facts. If she were not doing laudable work as chair of the journalism program at Brandeis University, the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer would make an excellent secretary of state. Her fine biography of Eunice Kennedy Shriver champions the overlooked sister, who deserves as much, if not more, applause than her celebrated brothers in establishing the family’s monumental legacy.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World

by Kitty Kelley

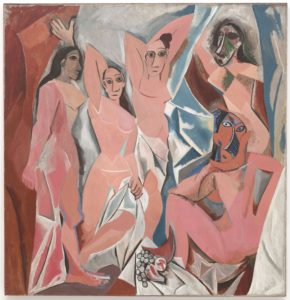

I had no idea until I read Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World by Miles J. Unger that Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” was so shocking. After visiting the Musée National Picasso in Paris last week, I would’ve pinned that ribbon on “Guernica” (1937), his mammoth evocation of the horrors of war. (Obviously, I missed the memo proclaiming sex more shocking than man’s inhumanity to man.)

I had no idea until I read Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World by Miles J. Unger that Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” was so shocking. After visiting the Musée National Picasso in Paris last week, I would’ve pinned that ribbon on “Guernica” (1937), his mammoth evocation of the horrors of war. (Obviously, I missed the memo proclaiming sex more shocking than man’s inhumanity to man.)

Strictly translated, “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” means the young, unmarried women of Avignon — the ancient town in southeast France in the Vaucluse, on the left bank of the Rhone. But elementary French does not capture Picasso’s revolutionary painting meant to rivet and revolt. As he said, “Art is not made to decorate apartments…It is an instrument of offensive and defensive war against the enemy.”

In 1907, Picasso’s enemy was “the centuries-old tradition” of art, which he attacked with his full artillery, producing a wall-size painting of five androgynous nudes with knife-sharp breasts, misshapen heads, and hollow eyes that looked fatigued and fed up with the sexual demands of their paying customers.

For Picasso, “Les Demoiselles” encompassed a narrative of lust and rage and repulsion and illicit desire. He stripped sex of all romance and displayed the brothel business as a basic transaction of cash for services rendered.

“Indeed, the dynamic interplay between the constructive and destructive principles, Freud’s Eros and Thanatos, was the key to the artist’s creativity,” states the author. At the time, those accustomed to the idealized nudes of Botticelli’s “Venus” and the soft Madonna curves of Raphael did not see Picasso’s masterpiece as creative, but rather as dark, disruptive, and dystopian.

In fact, he was shunned by his adoring bohemian disciples (aka, bande a’ Picasso), who were horrified when he pronounced the painting his glorious “exorcism.” Henri Matisse, his main rival among avant-garde artists in Paris, denounced “Les Demoiselles” as a crime against art, an elaborate hoax, and a personal affront. Dealers and collectors fled, showing only disgust for the painting.

One left Picasso’s studio practically in tears, telling Gertrude Stein, the artist’s biggest patron: “What a loss for French art!” Gertrude’s brother, Leo, once a Picasso patron, called the painting “a horrible mess.” Picasso so scandalized the art world by his depiction of these hard-edged prostitutes that, after one studio showing, he rolled up his canvas and stashed it under his bed for nine years until the world caught up with his vision that introduced the school of painting known as Cubism.

Given the heaving shelves of Picasso books, and the fourth and final volume of the artist’s life to be published soon by Sir John Richardson, one has to applaud Unger, an art historian, for carving his own niche in the adoration wall that surrounds Picasso’s genius.

While the author genuflects to the artist’s protean talents, he does not spare the man holding the paintbrush. Unger describes Picasso’s whorehouse as “the great battlefield of the human soul, an Armageddon of lust and loathing but also of liberation, the site where our conflicted nature reveals itself in all its anarchic violence.”

Some might wish Unger had grappled more vigorously with Picasso’s misogyny and his well-documented cruelty to women, but his savagery remains palpable on the page. “An unrepentant male chauvinist,” Unger calls him, Picasso used and abused women, discarding wives, mistresses, and lovers like a snake shedding its skin. His art was his first priority in life. Everything else — family, friends, children, even pets — was sacrificed on the altar of his raging ambition.

At one point, Picasso and Fernande Olivier, his first true love and mistress of many years, decided to adopt a 13-year-old girl from a Paris orphanage. Within weeks, we learn, “Picasso’s feelings veered dangerously far from the paternal.”

A sketch he titled “Raymonde Examining Her Foot” shows her spreading her legs to Picasso’s devouring gaze. “There’s no indication that Picasso ever abused Raymonde,” writes Unger, “but it’s clear she aroused feelings in him that might have led to disaster. His attraction to adolescent girls, at least later in life, is well-documented.”

The youngster lived with Picasso and Fernande for four months, during which time he was working on “Les Demoiselles.” Then they decided a child was too much of a strain on his art and their relationship, so they returned Raymonde to the orphanage, discarding her along with her dolls.

One of the artist’s most despicable acts occurred in 1944, when Picasso, a Spaniard living in Paris during World War II, was spared military service. Famous and influential at the time, he refused to help his lifelong colleague Max Jacob, Jewish and homosexual, who, the author tells us, “died at Drancy while awaiting transfer to Auschwitz, after Picasso failed to intervene on behalf of his old friend.”

The young prodigy from Barcelona lived to be 91 years old. He became rich beyond his imaginings and made himself the most renowned artist of the 20th century, but he was hardly a man beloved. Like his art, Pablo Picasso never tried to please.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Robin

by Kitty Kelley

Shakespeare set the gold standard for honoring a beloved comedian no longer alive. In Act 5 of Hamlet, when the Prince of Denmark sees the skull of his father’s court jester, he nearly weeps: “Alas poor Yorick…A fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy…”

Shakespeare set the gold standard for honoring a beloved comedian no longer alive. In Act 5 of Hamlet, when the Prince of Denmark sees the skull of his father’s court jester, he nearly weeps: “Alas poor Yorick…A fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy…”

And now, in Robin, we come to another man of merriment — a comedic genius who has, unfortunately, been buried in a turgid biography. Melancholy suffuses this book like a shroud, but perhaps that’s because the 2014 suicide of Robin Williams still saddens those of us once dazzled by his ricocheting brilliance, his hilarious humor, his raucous one-man shows, and many of his movies, particularly Good Morning, Vietnam, Mrs. Doubtfire, Dead Poets Society, and Good Will Hunting, which earned him the Oscar for best supporting actor.

As his friend Billy Crystal said the first time he saw Robin Williams perform: “Oh, my god. What is this? It was like trying to catch a comet with a baseball glove.”

Alas, poor Robin. While your star shines, your biographer shambles.

Granted, the challenge of writing about someone of sparkling talent is daunting, but there’s no excuse for plodding prose from “a culture reporter for The New York Times,” which is how the author, Dave Itzkoff, identifies himself on the back of the book.

On page eight, Itzkoff describes a photograph of Williams’ mother: “Even in this black-and-white image, the soft sparkle of her blue eyes is unmistakable.” Later he writes: “Still, there were lessons that Juilliard could not teach Robin…itches it could not scratch.”

Itzkoff continues scratching in another chapter: “After all the extravagant ambitions he had chased in show business and all the self-indulgent itches he had been able to scratch, none of which had led to his finding fulfillment, maybe this was what he truly wanted in life — maybe becoming a father is what would finally make him happy.”

The first few times Itzkoff mentions Williams wearing “rainbow suspenders,” I noted the colorful detail and remembered he had made them a fashion trend in 1978 with his breakout performance in the sitcom Mork and Mindy on network television.

By the fifth and sixth mention of “rainbow suspenders,” I wondered what I was missing. Was Itzkoff perseverating? His editor dozing? Were “rainbow suspenders” supposed to be Robin’s Rosebud? Did he wear them for good luck? To support the LGBTQ movement? I still don’t know.

By the age of 35, Dave Itzkoff had written two memoirs about himself, recalling his father’s cocaine addiction, his own drug use, and his attempted suicide, which presumably sensitized him to the addictions that plagued Williams, who was open about his struggles with drugs and alcohol, and frequently used them to fuel his comedy. He told audiences:

“I believe that cocaine is God’s way of saying you’re making too much money.”

“The only difference between me and a leprechaun is I snorted my pot of gold.”

“An alcoholic is someone who violates their standards faster than they can lower them.”

By contrast, discussing his decision to finally get sober, which he was for the last eight years of his life, Williams said: “I had to stop drinking alcohol because I used to wake up nude on the hood of my car with my keys in my ass. Not a good thing.”

When his second wife divorced him because of his extra-marital affairs, Williams said, “I’ve learned this: There’s (sic) penalties for early withdrawal and depositing in another account.”

Itzkoff covers all the biographical bases: Williams’ lonely childhood, his family’s many moves, his imaginary playmates, aloof parents, different schools, bullying, and the fear of disapproval and rejection, plus a bottomless need to please and perform, to be noticed and applauded.

No surprise that the best lines in the book belong to Williams, who psychoanalyzed himself better than anyone could: “I don’t think I’ll ever be the type that goes, ‘I am now at one with myself’…therapy helps…it makes you reexamine your life, how you related to people. How far you can push the ‘like me’ desire before there’s nothing left of you to like.”

Williams joked that he had to work nonstop because divorce was expensive, but the book makes clear that he worked for the same reason a dervish whirls — he had to. As one friend said, “He operated on working. That was the true love of his life. Above his children, above everything. If he wasn’t working he was a shell of himself. When he worked, it was like a lightbulb was turned on.”

Robin Williams turned the lightbulb off on August 11, 2014, when he hung himself by a leather belt. Months before, he had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, leading many to assume that depression prompted his suicide. But three months later, the Marin County Sheriff’s office released the autopsy report, showing that Williams suffered from “diffuse Lewy body dementia,” a toxic, devastating brain disorder for which there is no cure or control.

“Robin was aware that he was losing his mind and there was nothing he could do about it,” said one of his doctors. Billy Crystal said: “My heart breaks that he suffered and only saw one way out.”

Williams left behind one widow, two ex-wives, three children, and an estate worth $20-$50 million, which was litigated by some of the above. He left the rest of us a legacy of laughter but feeling as desolate as Hamlet over Yorick: “Where be your gibes now? Your gambols? Your flashes of merriment that were wont to set the table in a roar?”

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Jackie, Janet & Lee

by Kitty Kelley

Nothing sells like sex, diets, and the Kennedys. A book entitled How JFK Made Love to Marilyn Monroe on 150 Calories a Day would zoom to instant success. Just ask J. Randy Taraborrelli, who’s been mining two of those veins for the last 20 years and claims “many New York Times best sellers” to his credit.

Nothing sells like sex, diets, and the Kennedys. A book entitled How JFK Made Love to Marilyn Monroe on 150 Calories a Day would zoom to instant success. Just ask J. Randy Taraborrelli, who’s been mining two of those veins for the last 20 years and claims “many New York Times best sellers” to his credit.

In 2000, he wrote Jackie, Ethel, Joan: The Women of Camelot, which became a two-part TV series on NBC in 2001. He wrote After Camelot in 2012, and he now offers Jackie, Janet & Lee: The Secret Lives of Janet Auchincloss and Her Daughters Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Lee Radziwill.

Spoiler alert: He adores Jackie and abhors Lee. The big reveal, according to his publisher’s press release, is that (supposedly) their mother performed do-it-yourself artificial insemination to get pregnant twice after she divorced their father and married her second husband, Hugh D. Auchincloss.

Janet was 37; Hugh was 58, and he had had three children by two previous wives. Yet we’re told to believe that Mr. Auchincloss was incapable of impregnating Mrs. Auchincloss in 1945 and again in 1947. And — hang on — we’re told why: “Even though Hugh was not able to sustain an erection, he was able to produce sperm…[and Janet] used a kitchen utensil along the lines of a turkey baster — though it would be incorrect to say that this was the specific instrument she used; no one can quite remember…”

With eyes popping, I turned to the chapter notes for documentation on this “never before revealed secret.” Under source notes for “Janet’s Unconventional Pregnancy,” Taraborrelli writes: “Because of the sensitive nature of this chapter, my interviewed sources asked to remain anonymous.”

Huh?

With Mr. and Mrs. Auchincloss deceased for many years, I wondered what possible “sources” could’ve been interviewed about the intimacies of their bedroom. No documentation is provided, other than the author’s note that he recycles sources from his previous books. Then, like a bird feathering its nest, he snatches twigs and wisps from newspapers, magazines, and tabloids while plucking from the vast trove of other published lore, which Jill Abramson, in the New York Times, once estimated to be 40,000 Kennedy books.

In this book, some readers might be troubled by the lack of attribution for “she felt,” “he thought,” “said an intimate,” “revealed an associate,” “confided an employee,” and “reported someone with knowledge of the situation.”

Others might be puzzled by the personal quotes Taraborrelli does attribute, particularly a story about Janet giving Lee a check for $650,000, saying: “For any time I ever let you down, I’m very sorry. Maybe this small gift will make your life a little easier. I love you, Lee.”

Taraborrelli follows with: “We don’t know Lee’s reaction; she’s never discussed it and only she and Janet were in the room at the time the gift was presented.” So how is it that Taraborrelli, who was not in the room, can gives us Janet’s exact words?

Perhaps the quotes come secondhand from Taraborrelli’s main source for this book: James “Jamie” Auchincloss, the 71-year-old son of the aforementioned parents and the half-brother of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Lee Radziwill, although Taraborrelli tells us: “[H]e never refers to Jackie and Lee as ‘halfs.’”

Full disclosure: I interviewed Jamie Auchincloss several times in 1975 when I was writing a biography of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. That book, Jackie Oh!, received attention because my interview with former Florida senator George Smathers was the first time a Kennedy intimate had gone on the record to discuss the president’s extra-marital affairs.

During our three-hour interview in his law office, Smathers also confirmed that Jacqueline Kennedy had received electroshock therapy for depression after losing her first child, Arabella, in 1956. Published 20 years later, my book also revealed for the first time the prefrontal lobotomy performed on the Kennedys’ eldest daughter, Rosemary, who was severely diminished by the surgery, and, as a result, spent the rest of her life in the care of the nuns at St. Coletta’s in Wisconsin.

While Jamie Auchincloss was not the source for those revelations, he did speak openly about his famous relatives and, unfortunately, he paid a price. Appearing on Charlie Rose’s local DC talk show a few years later, he said that Jackie stopped speaking to him after my book was published, much as she had with others whom she felt had shared too much personal information about the late president, including Ben Bradlee, who wrote Conversations with Kennedy, and Paul “Red” Fay, JFK’s Navy buddy, author of The Pleasure of His Company. When Fay sent his royalty check to the Kennedy Library, Jackie sent it back.

A few years ago, Jamie Auchincloss plunged from the height of being the 6-year-old page boy who carried the wedding train of his sister’s gown when she married John F. Kennedy to the scandal of being jailed at age 67 for the possession of child pornography. In 2009, he pleaded guilty to distributing what prosecutors called lewd and lascivious images, and was charged with two felony counts for encouraging child sexual abuse.

He spent Christmas 2010 in jail. Failing to cooperate with his court-ordered sex offender treatment program, he was sentenced to eight months in jail, serving just over half the time behind bars and the rest in home detention. He was put on probation for three years and ordered to stay away from children for the rest of his life and to register as a sex offender.

Taraborrelli writes that “this unfortunate turn in Jamie’s life in no way impacts his standing in history or his memories of growing up with his parents…and siblings…Or his brothers-in-law, Jack, Bobby, and Ted Kennedy. The times I spent with Jamie were memorable; I appreciate him so much. He also provided many photographs for this book.”

If you’re a reader who requires corroborated information and credible sourcing in your nonfiction, this book may give you pause. Then again, if your requirements are less stringent, you might enjoy the photographs.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

“Martin’s Dream Day” Chosen for ILA Teachers’ Choices Reading List

The International Literacy Association (ILA) on May 1, 2018 announced the winning titles of the 2018 Choices reading lists: an annual selection of outstanding new children’s and young adults’ books, curated by students and educators themselves. These lists are issued during Children’s Book Week each year.

The International Literacy Association (ILA) on May 1, 2018 announced the winning titles of the 2018 Choices reading lists: an annual selection of outstanding new children’s and young adults’ books, curated by students and educators themselves. These lists are issued during Children’s Book Week each year.

This year, Martin’s Dream Day by Kitty Kelley was included as a Teachers’ Choice for Intermediate Readers (ages 8-11).

Each year, thousands of children, young adults, and educators around the United States select their favorite recently published books for the International Literacy Association’s Choices reading lists. These lists are used in classrooms, libraries, and homes to help readers of all ages find books they will enjoy.

The International Literacy Association (ILA) is a global advocacy and membership organization dedicated to advancing literacy for all through its network of more than 300,000 literacy educators, researchers and experts across 78 countries. With over 60 years of experience, ILA has set the standard for how literacy is defined, taught and evaluated. ILA collaborates with partners across the world to develop, gather and disseminate high-quality resources, best practices and cutting-edge research to empower educators, inspire students and inform policymakers. ILA publishes The Reading Teacher, Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy and Reading Research Quarterly.

The International Literacy Association (ILA) is a global advocacy and membership organization dedicated to advancing literacy for all through its network of more than 300,000 literacy educators, researchers and experts across 78 countries. With over 60 years of experience, ILA has set the standard for how literacy is defined, taught and evaluated. ILA collaborates with partners across the world to develop, gather and disseminate high-quality resources, best practices and cutting-edge research to empower educators, inspire students and inform policymakers. ILA publishes The Reading Teacher, Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy and Reading Research Quarterly.

“Martin’s Dream Day” is Woodson Honor Winner

National Council for the Social Studies “established the Carter G. Woodson Book Awards for the most distinguished books appropriate for young readers that depict ethnicity in the United States. First presented in 1974, this award is intended to ‘encourage the writing, publishing, and dissemination of outstanding social studies books for young readers that treat topics related to ethnic minorities and race relations sensitively and accurately.’”

2018

Elementary Level Honoree

Martin’s Dream Day

by Kitty Kelley

Atheneum Books for Young Readers

Avedon: Something Personal

by Kitty Kelley

If you’re into pop culture, you’ll inhale Avedon: Something Personal by Norma Stevens and Steven M.L. Aronson, which drops more names in 700 pages than a prison rollcall.

If you’re into pop culture, you’ll inhale Avedon: Something Personal by Norma Stevens and Steven M.L. Aronson, which drops more names in 700 pages than a prison rollcall.

If you recognize Kate and Naomi and Veruschka and Christy as first-name fashion models, you might pay $40 for the book, but you won’t see any of Richard Avedon’s acclaimed work for Bazaar or Vogue in it. You’ll read about “his iconic image of Dovima and the elephants,” but you won’t see why the image is iconic.

You’ll learn that Calvin Klein paid Avedon “three million in 1980 dollars” ($9.6 million in 2018 dollars) for the famous ad campaign showing a young Brooke Shields in an unbuttoned blouse and blue jeans saying, “Nothing comes between me and my Calvins.”

But, again, no photo.

Astonishingly, this biography of a world-renowned photographer contains none of his photographs.

Avedon was as celebrated for his black-and-white portraits as his fashion photography, but unless you know his work, you won’t understand why these portraits raised the ire of some of his subjects, like Truman Capote, whose “puffy-faced” image is described but not shown.

And neither are Avedon’s “vaunted picture of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor,” described as “two people without a country and without a soul,” and the photographer’s “highly controversial” and “fraught” portraits taken “relentlessly” of his terminally ill father during the months he was dying.

There are snapshots by others throughout the book, but none by Avedon himself. Apparently, this omission is because his images are controlled by the Avedon Foundation, which did not bless the book. In fact, the foundation issued a statement blasting the biography as filled with factual errors (some 200) and fantastical stories, which it claimed could damage Avedon’s legacy.

His son, John, called the book “a collection of half-truths or outright falsehoods,” particularly the last scene in which he prepared a meal and mistakenly sprinkled his deceased father’s ashes, rather than oregano, on the food.

A high school dropout who gravitated to intellectuals, Avedon was the beloved only son of an adoring Jewish mother. He loved theater and film and appeared to have read widely, as was evidenced by the nameplate on his building, which identified him as Dr. Aziz, the emotional character in E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India, whose quicksilver moods lifted him to heights of exuberance and cast him into the depths of despair.

“Avedon chafed at being defined a ‘fashion photographer,’ and longed to reign in the pantheon of artistes. To this end he published heavy books of his portraiture, staged gallery exhibitions and mounted museum openings, his proudest being twice honored at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Yet by the age of 75, he felt burned out creatively. He agonized over losing his focus, drive and energy, despite daily infusions of amphetamines and sleeping pills. Still, he never lost sight of his financial worth, saying: ‘Money is the only power in the world, and that’s my belief.’

“He once billed the New Yorker for over $1 million in expenses and sent his collected receipts in a large Tiffany box. He considered Qatar’s Sheikh Saud bin Mohammed bin Ali al-Thani to be his own ‘ATM on legs,’ and charged him ‘many millions’ for personal photography.”

The book’s most startling revelation is the 10-year love affair between Avedon and the director Mike Nichols. Despite their marriages to women (two wives for Avedon; four for Nichols, including his widow, Diane Sawyer), the men once considered leaving their spouses and running away together.

Avedon later confided to author Stevens that he could not publicly declare himself as gay because his self-proclaimed stature as “the world’s greatest photographer” would be diminished, and there was nothing he cared more about than his star in the stratosphere. “You do it, after I’m gone,” he told her. Stevens obliged — and then some. She retold his stories about “innocent kissing” with James Baldwin and youthful sexual encounters with his sister and his cousin.

This intimate biography draws on the recollections of Stevens and her 30 years with Avedon as his studio director and confidante, as well as oral histories from friends, associates, and a few disgruntled employees, all of whom acknowledge his creative genius as well as his relentless drive for national recognition.

Despite the bad blood between the foundation and the authors, which comes across clearly in the former’s public statement, nothing contested by the foundation rises to the level of libel, even allowing for no chapter notes indicating where the facts in the narration come from — no diaries, journals, or correspondence are cited as documentation.

Consumed by his legacy, Avedon counted the words in the death notices of his rivals and wondered if he’d get more or fewer. Particularly sad was his obsession over how the New York Times would cover his final exit. “Will I make the front page…Will I be above the fold?” To this end, he sent the newspaper annual but unbidden obituary updates listing his latest shows and exhibits.

Richard Avedon, 81, died of a cerebral hemorrhage while on assignment in San Antonio, Texas. The Times reported his death on the front page — below the fold.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Just a Journalist

by Kitty Kelley

If Linda Greenhouse is “just a journalist,” then Secretariat is just a horse. With a Phi Beta Kappa key from Radcliffe (1968) and a Pulitzer Prize (1998) “for her consistently illuminating coverage of the United States Supreme Court” for the New York Times, Greenhouse is the gold standard of journalism.

If Linda Greenhouse is “just a journalist,” then Secretariat is just a horse. With a Phi Beta Kappa key from Radcliffe (1968) and a Pulitzer Prize (1998) “for her consistently illuminating coverage of the United States Supreme Court” for the New York Times, Greenhouse is the gold standard of journalism.

(Full disclosure: Greenhouse is a friend, and I admire her — personally and professionally. She’s the woman so many would like to be: smart, accomplished, and principled.)

Her book, Just a Journalist: On the Press, Life, and the Spaces Between, not so much memoir as treatise, took root from a set of lectures she delivered in 2015 at her alma mater about the role of a journalist as a public person and a private citizen. She used herself as an example to pose provocative questions about the shifting boundaries in journalism and whether the old shibboleths remain effective in the 21st century, especially prescient now that we’re in the era of Donald J. Trump and his “fake news” and “alternative facts.”

Sparking her reflections on the subject was her personal experience following a speech she gave after receiving her college’s highest honor, the Radcliffe Medal. It was 2006, during the second term of George W. Bush, when, she told her audience, “Our government had turned its energy and attention away from upholding the rule of law and creating law-free zones at Guantanamo Bay, Abu Ghraib…and let’s not forget the sustained assault on women’s reproductive freedom and the hijacking of public policy by religious fundamentalism.”

She also talked about how the world had in some important ways gotten better, especially in the workplace for women and through the Supreme Court’s recognition of gay men and lesbians’ rights to “dignity” and “respect.”

Greenhouse took heat for expressing herself on these matters of verifiable fact, all part of the public record and covered in depth by the media. She did not reveal state secrets or endanger national security. She simply offered her opinion on the world at that time. Still, her peers pounced.

National Public Radio’s website ran a story headlined “Critics Question Reporter’s Airing of Personal Views.” Among the critics was the Washington bureau chief of the Los Angeles Times, who was shocked — shocked! (Like Claude Raines in “Casablanca.”) The dean of the journalism school at the University of Maryland pronounced her remarks “ill-advised.”

The former chair of the Pulitzer Prize board executive committee said, “The reputation of Greenhouse’s newspaper is at stake when the reporter expresses her strong beliefs publicly.”

The coup de grace was delivered by her own newspaper, whose public editor recommended she not cover the Supreme Court on topics she addressed in her speech. “Ms. Greenhouse has an over-riding obligation to avoid publicly expressing these kinds of personal opinions…[and] giving the paper’s critics fresh opportunities to snipe at its public policy coverage.”

They all sounded like Chicken Little, convinced the sky was going to fall on the New York Times because one of its reporters had expressed herself on public policy. Actually, the sky had fallen two years before, when Jayson Blair was forced to resign from the newspaper for fabricating or plagiarizing half of the 72 stories he had written.

The newsroom was still reeling from that debacle, which may have been why no one stepped forward to defend Greenhouse for telling the truth. She was like the child in the Hans Christian Andersen fairytale who called out the emperor for not wearing clothes. (To the Times’ credit, she continued covering the court until she retired in 2008, when she accepted an offer to teach at the Yale Law School.)

Greenhouse blows holes through the current theory of objectivity that journalists are expected to maintain — to have no private opinions or support any private causes. According to these old rules, journalists should not contribute to their community because it might reflect negatively on their employer or tempt others to see bias in their work. Leonard Downie took this to pious extremes when he was executive editor of the Washington Post and announced that he would not vote and would stop having “private opinions about politicians or issues.”

He felt that would give him a completely open mind in supervising the newspaper’s coverage, and I suppose it would in Brigadoon. But what about the real world, where journalists might want to participate in parent-teacher associations, volunteer for community organizations, contribute to nonprofits, and — God help us — register to vote?

Greenhouse asks how journalists can be objective in their coverage by adhering to “he said, she said” reporting, as if there are only two sides to every story, when, in fact, there are usually several. Under deadline, reporters, trying to be neutral, frequently run to official sources to get their quotes for “on the one hand, on the other hand” presentations. The advocates’ words could be lies or, to use the newspaper euphemism, “factual untruths,” or benign lobbying for their particular causes.

If their words come to the reader without context or correction, they gain credibility for simply being quoted in the news. Hardly neutral reporting. In fact, just the opposite, as these journalists, striving to be fair and balanced, are, according to Greenhouse, doing what they most dread —deferring to power.

Normally, a journalist writing about journalism is like a golfer writing about golf; interesting only to those who play the game. In this case, though, we’ve got a Babe Didrikson Zaharias holding forth on a subject for which she holds the field, and her subject is not “just” journalism, as if journalism is a mere incidental that can be shrugged off with indifference.

In arguing for more context in reporting, Greenhouse echoes the wisdom of Felix Frankfurter, who said: “The responsibility of those in power is not to reflect inflamed public feeling but to help form its understanding.”

While her questions are provocative and meant to be pondered, her style is cool, analytical, and without hyperbole. She writes with restraint and offers no harsh criticism of her former employer. To the contrary, she recognizes the premier position the New York Times holds and wants nothing more than for the paper of record to excel in its mission to inform.

Journalism affects all of us — locally, nationally, internationally. For it’s through journalists that we learn what’s happening in our world and how to traverse its shoals. Journalists are our eyes and ears, and without seeing and hearing, we’d be blind and deaf, unable to function. Linda Greenhouse’s little 192-page book is a big contribution and deserves our attention.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

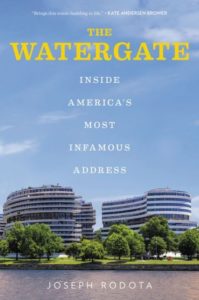

The Watergate: Inside America’s Most Infamous Address

by Kitty Kelley

Hotels can intrigue, even captivate. In the pantheon of places, nothing tantalizes so much as a good story situated in a hotel, particularly a luxury hotel with hot- and cold-running bellhops, genuflecting valets, and chandeliers that drip with crystal. (Think the Metropol in A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles.)

Hotels can intrigue, even captivate. In the pantheon of places, nothing tantalizes so much as a good story situated in a hotel, particularly a luxury hotel with hot- and cold-running bellhops, genuflecting valets, and chandeliers that drip with crystal. (Think the Metropol in A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles.)

Built on superstition, few hotels have a 13th floor — most elevators go from 12 to 14 — but each floor can hold secrets, whether dreadful or delightful. As such, hotels have been the subject of movies (“Grand Hotel” with Greta Garbo; “The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel” with Judi Dench); novels (Hotel Du Lac by Anita Brookner); children’s books (Eloise at the Plaza by Kay Thompson); a rollicking BBC television series (“The Duchess of Duke Street,” the story of the king’s mistress, who owned the Cavendish Hotel in London); and even an Elvis Presley classic (“Heartbreak Hotel”).

Hotel sites beguile, possibly because they provide escapes from the real world and adventures for the escapees, which translates into vicarious pleasure for the rest of us.

Whether fact or fiction, the standard recipe for a good hotel story contains basic ingredients:

1 lb. Scandal

1 c. Sex

2 c. Eccentric guests

1 dash Crime

1 pinch Skullduggery

For added spice, mix in two cups of chopped celebrity and bake for 350 pages. Voila. You’ve got the perfect hotel-story soufflé.

Joseph Rodota followed this recipe to write his first book, The Watergate: Inside America’s Most Infamous Address. For scandal, crime, and skullduggery, he provides the 1972 burglary of the Democratic National Committee, which led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon, which, in turn, spawned a great film, “All the President’s Men.”

For eccentricity, Rodota showcases Martha Mitchell, wife of Nixon’s attorney general, and her midnight phone calls. Freshly sprung from a psychiatric ward in New York to move to Washington with her husband after Nixon’s inauguration, Martha soon gave hilarious definition to drinking and dialing. Belting back bourbon late at night, she frequently called Helen Thomas, UPI’s White House correspondent, to unload on “Mr. President.”

For eccentric good measure and a smidge of sex, Rodota also tosses in the Chinese hostess (cue Anna Chennault) who served “concubine chicken” at her Watergate dinner parties.

From John F. Kennedy to John Mitchell to the johns who paid for prostitutes, this book drops more names than a prison roll call. With the exception of Monica Lewinsky, who lived in her mother’s Watergate apartment in the 1990s, where she hung the blue dress that led to the impeachment of President Bill Clinton, most of the dropped names are Nixon-era Republicans (Senators Elizabeth and Bob Dole), Rosemary Woods, and cabinet members like Maurice Stans, John Volpe, and Emil “Bus” Mosbacher.

With skillful research from old newspapers and magazines, oral histories from presidential libraries, and a few interviews, Rodota has fashioned an interesting story about the white concrete edifice that looks like a giant clamshell. With three buildings of wrap-around co-op apartments terraced with egg-carton balustrades, the Watergate, facing the Potomac River, sits adjacent to the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

To tell his story from the beginning, Rodota burrows into the complicated bureaucracy that surrounds any major construction in the nation’s capital. He whacks through the weeds of proposals and counter-proposals from the financiers, architects, and developers to the National Capital Planning Commission, the DC Zoning Commission, the National Park Service, the Commission on Fine Arts, the committee overseeing the National Cultural Center (later to be named the Kennedy Center), the U.S. Congress, and, finally, the White House. All had to reach agreement before a shovel broke ground.

Beginning in 1962, numerous hearings were held to discuss plans for Watergate Towne, a complex that would include a gourmet restaurant, spa, beauty salon, grocery store, liquor store, cleaners, florist, bakery, and a boutique of designer clothes for women. Still, there was concern, especially over the project’s financing and what the Kennedy White House called “the Catholic problem.”

As the first Catholic to be elected president — and only by 100,000 votes — John F. Kennedy knew his religion was problematic to many. As president, he genuinely wanted to make Washington “a more beautiful and functional city,” which the Watergate project promised to do. But he would not sign off on the $50 million proposal because it was largely underwritten by the Vatican, then the principal shareholder in the developing company Società Generale Immobiliare.

The formidable columnist Drew Pearson stoked controversy over “popism” with a syndicated column headlined: “Vatican Seeks Imposing Edifice on Potomac.” A group called Protestants and Other Americans United for Separation of Church and State mobilized its members.

Within weeks, the White House received more than 3,000 letters opposing construction of the Watergate and, according to one, “having Miami Beach come to Washington.” Most voiced outrage that Kennedy would be under clerical pressure to do the bidding of “the world’s richest church.” The Vatican soon divested its interest in the project, and, by November 22, 1963, most objections were muted.

Probably because there is no breaking news in Rodota’s book, his publisher sent a letter to editors and producers trying to burnish the fact that “The Vatican, the coal miners of Britain, and Ronald Reagan have something in common: They each owned a piece of the Watergate. Ronald Reagan held a financial stake in the Watergate complex shortly before becoming president, a fact that has never been made public before this book.”

Wowza! Stop the presses!

Yet the author does a good job of mixing historical facts with personal anecdotes to tell the story of what was both the most famous and most infamous hotel in Washington, DC, until the presidential election of 2016. Perhaps Rodota will follow this book with another hotel story entitled Tales from the Trump International, which might indeed provide some needed wowza.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Remembering Marianne Means

by Kitty Kelley

I’d much rather be hoisting a glass with Marianne Means, and hearing her rant about “that vulgarian” in the White House than writing this valedictory, but she went to the angels a few days ago, and her death leaves me with an empty glass, albeit a full heart.

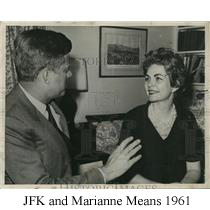

You may have noticed The Washington Post gave her a large obituary, and applauded her as a “trailblazing White House correspondent,” which led to 50 successful years as a syndicated columnist for Hearst newspapers. The obit mentioned that Marianne made a crucial connection as a college student with then-Sen. John F. Kennedy, when he was campaigning for President in Nebraska. In the White House he sought to help her make her way amidst a predominantly male press corps.

You may have noticed The Washington Post gave her a large obituary, and applauded her as a “trailblazing White House correspondent,” which led to 50 successful years as a syndicated columnist for Hearst newspapers. The obit mentioned that Marianne made a crucial connection as a college student with then-Sen. John F. Kennedy, when he was campaigning for President in Nebraska. In the White House he sought to help her make her way amidst a predominantly male press corps.

“Give her some stories,” the President told one aide. “Give her all the help you can.”

For anyone who knew Marianne then as a pretty blue-eyed blonde—“farm fresh,” recalled one photographer—and JFK as an inveterate chaser, certain assumptions were made, and those assumptions were to Marianne’s advantage, although her romance then was not with Kennedy, but with his deputy press secretary.

I met her many years later in Georgetown, where she lived all of her life since moving from her parents’ farm. She graduated from the University of Nebraska with a Phi Beta Kappa key, and later earned a law degree from George Washington University. We lived near each other, shared the same hairdresser and many mutual friends. Marianne was great fun, wonderfully opinionated, and breezily direct about everything—except for her husbands and lovers. By the end of her life she’d collected five of the former and lots of the latter, but she did not kiss and tell. She would’ve been appalled by #MeToo.

Before Pamela Harriman arrived in Washington, Marianne Means was entertaining presidents, vice presidents, senators and congressmen. “Not all at once, mind you. I saved Lyndon Johnson for a special group of people,” she told me in 1973 when I was writing an article about dinner parties. “As President he came to my house two times. Both times Lady Bird was out of town and both times he approved the guest list in advance.” I asked if she catered an elaborate menu for her illustrious guest. “Can you believe it? I actually cooked it myself,” she said. “The President was not a fussy eater, thank God, so I could get away with a simple dinner of roast beef, which was good because I’m just a plain old meant-and-potatoes girl.”

In the article I mentioned her cat had jumped on President Johnson’s lap. After publication Marianne corrected me: the cat had jumped on the roast beef.

When I was thinking about writing a book on Georgetown as the nexus of power and influence in Washington, D.C., Marianne was my go-to source. She knew that few places in the U.S. carried the panache of instant recognition like the 12 square blocks in the middle of the nation’s capital, which have been home to presidents and prostitutes, senators and scalawags, congressmen and convicts. Even when I decided not to write the book, we’d still meet for dinner at La Chaumiere, where she would be wheel-chaired in by one of her devoted caregivers.

One night she began talking about LBJ, and I gave her the girlfriend-to-girlfriend look. She laughed, but wouldn’t say another word. I mentioned the many references to her in President Johnson’s daily White House diaries from 1964-1967.

“Okay,” she said. She paused for a long minute. “Yes, it was an affair and, no, I won’t share it with people, not even you. It was mine and he was mine.” She was serious, almost fierce, and I realized that Lyndon Baines Johnson had been enormous in her life. Later that was confirmed when I read John Seigenthaler’s oral history in the John F. Kennedy Library regarding the 1964 Democratic National Convention when Robert Kennedy was given a monumental ovation The rancor between then-President Johnson and former Attorney General Kennedy was visceral. Seigenthaler, administrative assistant to Kennedy in the Justice Department, was a close personal friend. Flying back to Washington on the press plane after the convention, he recalled: “I remember Marianne Means who loved Lyndon and really worked on Bob. She was always a friend of mine. [But] I was cold to her on the flight that night.”

During out last dinner Marianne said to me: “I think it’s terrible Johnson has not gotten his due as a great president and he was a great president. Look at all he did for civil rights.”

I agreed, then whispered, “Vietnam.”

“Pew,” she said. (Yes, “pew” was her exact quote.) “Vietnam was started by another president…. Johnson made sure both his sons-in-law [Patrick Nugent and Charles Robb] served—in safe positions, of course, but both went to Vietnam…. Ben Barnes [former Lt. Gov. of Texas] is now the leading guy for helping us try to restore Johnson’s place in history.”

She talked about inviting President Johnson to one of her weddings. “I think it was my second or third…. It was in my small house on 32nd Street. Johnson came. My relatives still remember how they had left something in the car and had to run outside to get it but couldn’t get back in because of the Secret Service.”

“Must be nice to have a lover who is protected at all times,” I said.

“Nice try, Kitty Poo, but I still won’t tell you.”

We both laughed at my clumsy effort to get more information, and now she, God bless her, gets the last laugh.

Photo: Kitty Kelley (seated); Standing, left to right: Barbara Dixon, Susan Tolchin, Marianne Means and Sandra MacElwaine.

Crossposted with The Georgetowner