At the Leon Levy Center for Biography

Patrimony: A True Story

by Kitty Kelley

One of life’s toughest journeys is accompanying a loved one into old age or disability, for it is a trip that will inevitably lead to the grave, and that final farewell can bring crushing grief and an awful aloneness.

One of life’s toughest journeys is accompanying a loved one into old age or disability, for it is a trip that will inevitably lead to the grave, and that final farewell can bring crushing grief and an awful aloneness.

In Patrimony: A True Story, published in 1991, Philip Roth made that journey with his 86-year-old father, who had been struck by a virulent brain tumor, leaving him “utterly isolated within a body that had become a terrifying escape-proof enclosure, the holding pen in a slaughterhouse.”

With unsparing prose, Roth chronicles the last two years of his father’s life, which became a horrifying excursion into modern medicine — different doctors with various diagnoses and misdiagnoses, some which required crippling surgeries by men the author “wouldn’t trust to carve my Thanksgiving turkey.”

The questionable results and protracted recovery left father and son bewildered and frustrated as they tried to make wracking decisions about prolonging life and postponing death. In the end, they decide against all surgeries and try to deal with the effects of the growing tumor, which leave Herman Roth disfigured with facial paralysis, deaf in one ear, and blind in one eye.

Through the son, we come to know the father as “obsessively stubborn and stubbornly obsessive,” a “pitiless realist” who tossed out his wife’s clothes hours after she died. Philip Roth’s mother had been “a good-natured, even tempered, untroublesome partner whose faults and failings [his father] could correct unceasingly.”

We see “the poignant abyss” between the pair — the father, two generations removed from Galicia in Northern Spain with only an eighth-grade education, whose hard work as an insurance salesman for Metropolitan Life in Newark made it possible for the son to be educated, the elixir that would elevate him realms beyond his parents — socially, intellectually, and professionally.

“I had prematurely entered high school at the age of twelve, just about the age when [my father] had left for good to support his immigrant parents,” Roth writes.

Obviously gifted, Roth graduated college magna cum laude and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. Throughout, he felt guilty about outdistancing his father, and reflects that “every course I took and paper I wrote was expanding the mental divide that had been growing wider and wider.”

He earned his M.A. in literature from the University of Chicago, became a Distinguished Professor at Princeton, wrote 32 books of fiction and nonfiction, and won almost every literary prize imaginable.

For many years, Roth distanced himself from his hectoring father, who, he writes, “had no idea just how unproductive, how maddening, even, at times, cruel his admonishing could be.” Yet he pays him loving tribute for being a survivor: for surviving financial setbacks, for surviving an immigrant’s humiliations, for surviving a Jew’s discrimination in the claws of anti-Semitism.

Father and son finally bond over their shared passion for baseball, a bit reminiscent of Field of Dreams. One of the most affecting scenes in the book is Roth’s recollection of game five of the playoffs between the Mets and the Astros on October 14, 1986, when he was in London, six hours away from the game his father is watching in New Jersey.

Their transcontinental conversation sounds like a play-by-play between two exuberant boys until the father remembers his son is calling from England. “Hey…This is going to cost you a fortune.” Ecstatic that his father’s tumor has given him enough remission to enjoy the game, Roth urges him to continue. “Go ahead, Herm. I’m a rich man. Pitch by pitch. Who’s up?”

Roth found his father in advanced age to have become “annoyingly tight” about spending money on himself for a cleaning lady or for a subscription to his beloved New York Times. One wonders why the “rich” son did not step forward to provide those small luxuries, indicating perhaps that the leaf does not fall far from the tree.

Yet, as a good son, Roth stepped up to usher his father through his last 24 months of life, taking care of him as one might a newborn child. He drew his Epsom salt baths, tested the water, helped him in and out of the tub, and observed — only as the author of Portnoy’s Complaint would — that his father’s member “looked pretty serviceable. Stouter around, I noticed, than my own.”

Roth’s writing here is extraordinary but hardly elevating. As the New York Times proclaimed, Patrimony is “American storytelling at its least lyrical.” One of the “least lyrical” parts of this memoir, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award, is the breath-stopping scene of the father’s incontinence in his son’s home, where the old man dissolves into tears and shamefully admits, “I beshat myself.”

The son goes down on his hands and knees, stifling disgust and nausea, to clean a bathroom floor full of his father’s excrement, which, he relates with mordant humor, is true patrimony. “And not because cleaning it up was symbolic of something else, but because it wasn’t, because it was nothing less or more than lived reality.”

Roth saw his patrimony not in inherited wealth or the accumulated treasures of a lifetime from his father, but in cleaning up his father’s befoulment.

On his last day of life, Herman Roth was rushed to the hospital, unable to breathe. The attending physician was prepared to take “extraordinary measures” to keep him alive when Philip Roth arrived and had to decide whether to follow his father’s living will, which stipulated no life support. He writes that he had to sit with his father a very long time before he could say, “Dad, I’m going to have to let you go.”

Only at the end of the book do we learn that “in keeping with the unseemliness of my profession,” Philip Roth had been writing this memoir all the time his father was ill and dying.

Many will be grateful that he did.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Life of David Hockney: A Novel

by Kitty Kelley

People who know art will recognize the name of David Hockney, and those who like the artist will enjoy this romp of a book, which purports to be “a novel and a biography,” a hybrid of sorts that cross-fertilizes fact with fiction. Brief and breezy at under 200 pages, the Life of David Hockney by Catherine Cusset reads like a fanzine about the man considered to be England’s most famous living artist.

People who know art will recognize the name of David Hockney, and those who like the artist will enjoy this romp of a book, which purports to be “a novel and a biography,” a hybrid of sorts that cross-fertilizes fact with fiction. Brief and breezy at under 200 pages, the Life of David Hockney by Catherine Cusset reads like a fanzine about the man considered to be England’s most famous living artist.

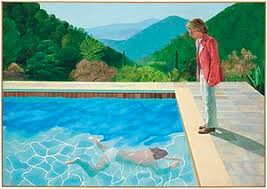

At the age of 35, Hockney made auction history in 2018 when his “Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures),” painted in 1972, sold for $90 million. He held that record for six months until Jeff Koons’ “Rabbit” sold for $91 million.

Cusset wrote this book as a love letter and said as much during an interview on NPR: “I hope he will consider it an homage.” She admitted she “was very scared” about his reaction. “The man…is very rich and he’s super well known. And he cares about his image. And he can hire very good lawyers.”

She needn’t have worried. Hockney has flicked off major art critics like Hilton Kramer and Clement Greenberg for disparaging his work as “superficial” and too pleasant to be taken seriously; then he’s laughed all the way to the bank. Upon publication of Cusset’s book, Hockney was gracious: “[It] caught a lot of me. I could recognize myself.”

The author had not known anything about the artist until she looked at his work on the Internet. Then, “I really liked him…I loved his incredible freedom at every level…always following his desire, his impulse, being true to himself.”

Having written 13 novels about “things that are connected to my life — my mother, my mother-in-law [and] sex,” Cusset also holds two Ph.D.s — one from Paris Diderot University, where she wrote a dissertation on Marquis de Sade, and one from Yale, where she wrote on the 18th-century libertine novel. So, she’s well-schooled on the subject of sex and the pain and pleasures of the flesh.

As a gay man, Hockney celebrates homosexuality in much of his art (“We Two Boys Together Climbing,” “Doll Boy,” “Adhesiveness”); with staccato sentences, Cusset dives into his personal life like a devotee of True Romance pot-boilers. She reports on his nude revels — filled with poppers, cocaine, and Quaaludes — the fraught years of AIDS, and the sad deaths of many friends.

She tracks his torrid five-year affair with Peter, who becomes his model and muse. (Most of the men mentioned in the book, including friends and lovers and assistants, are identified by first names only.)

Then — cue the drums — comes the traumatic break-up with Peter, when he leaves the artist for a younger man. In sob-sister style, Cusset writes how Hockney “was stricken with depression” and kept asking himself, “How could he get Peter out of his blood?”

Even three years later, “He would still cry when he thought of Peter.” This leads to second-guessing their relationship:

“Had Peter ever had any real feelings for him?”

“Where was the boy whom he had loved so passionately?”

“Would the pain ever go away?”

“Weren’t three years enough?”

Cue the violins.

For those unfamiliar with Hockney’s art, this book will disappoint, as it contains no reproductions or illustrations. Cusset cites several works by name but describes few, probably figuring that fans will have read at least one of the artist’s 27 books and be able to recall images such as “A Bigger Grand Canyon,” “My House Montacalm Avenue Los Angeles,” and “Model with Unfinished Self Portrait.”

Still, to write about David Hockney without showing his paintings is like writing about Winston Churchill without quoting his speeches.

In discussing Hockney’s art, Cusset notes that the color blue suffuses many of his paintings, from the aqua swimming pools that first made him famous to his “Self Portrait with Blue Guitar,” inspired by Wallace Stevens’ poem “The Man with the Blue Guitar.”

This poem spoke to Hockney, who saw himself as a man who can’t play things as they are, but through his talent — his blue guitar — he summons the power to recreate the world from his imagination. The guitar is the artist’s talisman and can only be strummed by the gifted.

Life of David Hockney begins with a young, happy-go-lucky man who moves from the north of England to Los Angeles to pursue his passion for painting and music and beautiful boys. He bleaches his hair blonde, wears red polka dots with purple stripes, and, with a flair for friendship, surrounds himself with an adoring coterie that accompanies his rocket to success.

He achieves great wealth and global recognition. He travels the world, collecting all its tributes, and seems surely headed for happily-ever-after. But age and disability intrude, leaving the last image of David Hockney as a deaf 82-year-old man, sitting alone on his porch, smoking a joint that he buys with a medical marijuana license “to calm his anxiety.”

Fugit irreparabile tempus.

[Correction: This posting originally gave an incorrect date for the record-breaking sale of “Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)” ]

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Reconciliation

by Kitty Kelley

Mélisande Short-Colomb knows her begats. Three years ago, she received a Facebook message from a genealogist, asking if she was related to the Mahoney family of Baton Rouge. Like a Biblical scholar ticking off Old Testament lineage, she typed out a list of her forebears—enslaved and free—going back seven generations. The genealogist had struck gold. For months, she’d been searching for descendants of the roughly three hundred slaves who had been sold by the Maryland Jesuits who owned Georgetown College, in 1838, for a hundred and fifteen thousand dollars, to save the school from bankruptcy. With the help of Short-Colomb and her begats, more than eight thousand descendants of these slaves were located. Now Georgetown University is trying to make it up to them. Last month, the student body voted to pay reparations to the heirs.

Short-Colomb, who is sixty-five, with gray hair, is a rising junior at Georgetown. “I’m not just one of the oldest students here and one of the few African-Americans,” she said the other day. “I’m also part of the reconciliation program.” In 2016, the university began offering legacy status—a preference for admission, not a scholarship—to descendants of slaves owned by the Maryland Jesuits. One descendant has graduated, two are in graduate school, and three—including Short-Colomb—are undergraduates. “I’m here to help the Jesuits atone for their sins,” she said, smiling.

and one of the few African-Americans,” she said the other day. “I’m also part of the reconciliation program.” In 2016, the university began offering legacy status—a preference for admission, not a scholarship—to descendants of slaves owned by the Maryland Jesuits. One descendant has graduated, two are in graduate school, and three—including Short-Colomb—are undergraduates. “I’m here to help the Jesuits atone for their sins,” she said, smiling.

Short-Colomb was hanging out in her dorm, Copley Hall. Her room, which she calls her “tiny condo,” has a single bed, a large bathroom with grab rails, and a desk piled with papers, books, and a few crystals. She’s comfortable now, after what she calls the “trauma” of her first semester. “I was overwhelmed by everything that the young white students seemed to take in stride, if not for granted,” she said. “The kids all had the same look—leggings, puffy jackets, athletic shoes, and ponytails.” Short-Colomb, who had worked as a chef for twenty-two years, was used to wearing a uniform. “I didn’t know how to dress for college,” she said. “I looked strange walking around in my blue suède pumps.” That day, she had on a sweatshirt, sandals, and ripped, wide-legged jeans.

Last year, her window looked out on the school’s Jesuit cemetery. She would sometimes end her day watching the sun set over it. “I took a perverse pleasure in having survived the struggle of my ancestors,” she said. “I looked out at those Jesuit tombstones and was unapologetically grateful that they are dead and I am alive.” She admitted feeling bitter when she sees the African-American groundskeepers, knowing that the university had built over the former burial sites of slaves. “No brothers weeding and mowing their grounds,” she said.

The university isn’t bound by the student referendum to pay reparations, but the board of directors is expected to consider the recommendation in June. If it votes in favor, a reconciliation fee of twenty-seven dollars and twenty cents will be added to each undergraduate’s tuition bill. Short-Colomb helped rally the votes. Standing in a grassy quad, she’d announced, into a megaphone, “The dollar amount, symbolic of the two hundred and seventy-two Jesuit slaves sold, is only one-tenth of one per cent of the average tuition per semester.”

The result of the student vote is controversial on campus. Some students say that the university should pay its own reparations rather than make students fund them. International students have objected to paying for a crime that they didn’t commit. To the skeptics, Short-Colomb responds, “You came here voluntarily, and you’ll leave with the prestige of a degree from an esteemed university that would not exist but for the enslaved people who built it.”

Later that day, Short-Colomb cooked a gumbo dinner for her friend Richard Cellini, the founder of the Georgetown Memory Project. Cellini’s venture, which receives no financial support from Georgetown, has identified eight thousand four hundred and twenty-five descendants, more than four thousand of whom are alive. He hopes to locate even more and reunite fifteen hundred families who were separated by the 1838 sale.

Cellini, who describes himself as a “mustard-seed Catholic,” said that he knew very little about slavery or African-American history until a couple of years ago, when students began protesting after a story about the Georgetown slave auction ran in the student paper. “I could not stop thinking about the families ripped apart by that sale whose names had been in the university archives for years,” he said. Ironically, written records exist only because the Jesuits insisted that their slaves be baptized.

“We’ll save your soul while we sell your ass,” Short-Colomb joked.

Originally published in “Talk of the Town” in New Yorker print edition May 20, 2019

10/29/2019 Update on reparations at Georgetown University here.

The Drama of Celebrity

by Kitty Kelley

The Drama of Celebrity by Sharon Marcus is a hybrid of biography and sociological treatise on one of the most important phenomena of modern times. Marcus, the Orlando Harriman Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, sets the table with seven years of scholarly research to show why we are attracted to — or, conversely, repulsed by — celebrity culture.

The Drama of Celebrity by Sharon Marcus is a hybrid of biography and sociological treatise on one of the most important phenomena of modern times. Marcus, the Orlando Harriman Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, sets the table with seven years of scholarly research to show why we are attracted to — or, conversely, repulsed by — celebrity culture.

She begins by defining a celebrity as someone known around the world who has mastered the media and deliberately engaged the public. The aspiring celebrity must connect with the media to reach “the publics,” as Marcus calls them, and ignite the fuse that explodes into fame. All must dance together in a three-way waltz. Without that triangle, Marcus maintains, there can be no celebrity.

Celebrity culture began in the 18th century, when the public began to take an interest in authors, artists, performers, scientists, and politicians. Before then, only kings and conquerors were celebrities, which, by Marcus’ definition, were people known during their lifetimes to more people than could possibly know one another.

In profiling the life of the French actress Sarah Bernhardt, “the world’s greatest celebrity,” Marcus shows how a contrarian created celebrity culture by toppling tradition and breaking all the rules of conventional behavior. Bernhardt embraced the bizarre by posing in a coffin long before Lady Gaga publicly wore a gown of raw beef (which, by the way, made it to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, where it is preserved as jerky).

From the beginning of her career in 1870 until the day she died in 1923, “the divine Sarah” presented herself as the quintessential outsider. She was skinny when fashion prized full figures. French newspapers belittled her for being bony, much as today’s tabloids chide Lena Dunham for being chubby.

Born Jewish, and abandoned by her mother, Bernhardt was baptized Christian and raised in a convent. Yet, in an anti-Semitic world, she insisted on being seen as Jewish and changed her birth name from Rosine to Sarah to emphasize her Hebrew roots, which she knew would make her appear more exotic.

She was the first actress to stare directly at the camera when posing for photographs, an outrageous act for the 19th century, when even the most famous women did not dare to appropriate the self-entitled directness of men.

But Bernhardt did, making defiance the first commandment of becoming a celebrity. As Marcus writes, “She dared to show down her beholder.” She also dared to become famous on her own without benefit of a father or husband, unheard of for a woman at that time.

Throughout her life, Bernhardt shocked on stage and off; in doing so, she ruled as the most famous person on earth for five decades. She was so popular that theaters had to turn people away at the door of her performances. Touring the globe, she became an international sensation. She was Madonna squared, J-Lo times 10. As Mark Twain said, “There are five kinds of actresses: bad actresses, fair actresses, good actresses, great actresses, and Sarah Bernhardt.”

Bernhardt initiated celebrity endorsements when a rice powder (and then a cigar) was named for her. Women imitated her by wearing bunches of flowers the way she did, which paved the way for Audrey pants, Jackie dresses, and Farrah’s feathered flip. Bernhardt even became the subject of minstrel acts in which slim men impersonated her as “Sarah Heartburn” and “Sarah Barnyard,” setting the stage for Marilyn lookalikes and Elvis imitators.

The week after Bernhardt’s death, the queen of England ordered a Mass to be said for her at London’s Westminster Cathedral. One obituary noted: “The death of the most famous actress in the world is a fresh reminder that the stage still opens the widest door to the richest realm in which women win honor, fortune and popularity by their own talents and genius.”

A million mourners witnessed her funeral procession travel from her home in Paris to the cemetery. Her name and image dominated international newspaper headlines and magazine covers for weeks after her death, much like Diana, Princess of Wales.

Until the late 20th century, the word “celebrity” was a compliment, a term of genuine praise reserved for those who had accomplished something considered worthwhile, like Helen Keller, Muhammed Ali, Nina Simone, and Harry Belafonte, who used their celebrity to fight discrimination against minorities, and others, like Paul Newman and U2’s Bono, who used theirs to further humanitarian causes.

Marcus traces the accolade known as “celebrity” through the centuries to the Kardashian era, when the term became a pejorative of sorts. She ends her book with the example of a man known for his flamboyant headgear, his public boasts about sleeping with other men’s wives, his vast riches, and his provocative crudeness, which made him popular with white Americans who felt alienated from the country’s East Coast elites.

She refers, of course, to Davy Crockett (1786-1836), who opened the door for a 21st-century reality star to sit in the White House. Warns the author: “The history and theory of celebrity teach us that we get the celebrities we deserve.”

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

All That You Leave Behind

by Kitty Kelley

“The gods giveth and the gods taketh away.” So goes a biblical tenet from the Book of Job, which Erin Lee Carr confirms in her new book, All That You Leave Behind. With piercing honesty, she writes a dazzling drunk-a-log about her on-again, off-again struggle with sobriety, and examines which genes the gods gave her and which they took away.

“The gods giveth and the gods taketh away.” So goes a biblical tenet from the Book of Job, which Erin Lee Carr confirms in her new book, All That You Leave Behind. With piercing honesty, she writes a dazzling drunk-a-log about her on-again, off-again struggle with sobriety, and examines which genes the gods gave her and which they took away.

Her book is also a love letter to her father, David Carr, who wrote his own addiction memoir, The Night of the Gun, in 2008. He died seven years later at his desk at the New York Times. He was only 58, and his daughter, then 27, was inconsolable. She obviously wrote this book to find a way out of her grief, but even a year later, she writes that she could not bear to be “around women and their fathers.”

Erin was a daddy’s girl because Daddy was the only parent she had, even when he left her and her twin sister in a car in the dead of a Minnesota winter to get high in a crack house. Their mother, still alive and still drug-addicted, has not been in their lives since they were 14.

“Sorry Mom,” Erin writes in her acknowledgements, “I know this is hard for you.”

I came to this book because I admired David Carr’s reportage on film, media, and culture in the Times. I was riveted by his harrowing life story of down-and-out addiction, steel bracelets, and jail cells followed — heroically — by AA recovery, which, coupled with monumental talent, finally rocketed him to success as a journalist.

His daughter tells us it was his raging ambition to write his way to national recognition, and possibly a Pulitzer, that pushed him into the sobriety that finally saved him. The Pulitzer eluded him, but he attracted a huge following on Twitter and died at the crest of an accomplished career.

“Sort of a mic drop, really,” Erin writes. This might not seem like salvation to many but, given Carr’s epic battles with addiction, his five-plus decades on this planet were a triumph over lifespan logic.

David Carr bequeathed his talents and his torments to his daughter, who writes bravely about her struggles with sobriety and bracingly about the father she adored, who once told her: “Looking at you is like looking into a dirty mirror.”

She recalls that the comment stung in the moment and stung again when she wrote it. “It shows that he wanted me to be a mirror image of himself, but was disturbed when it actually looked like him.”

He was her father and mentor, “one relationship always in conflict with the other.” In both roles, he needed her to be successful to be part of his legacy: “You can either be a big deal in your own right or have a drinking problem for the next ten years and be of little significance,” she quotes him as saying. He prided himself on his golden Rolodex filled with famous names, “People I read about in my battered copies of Entertainment Weekly. He liked to name drop.”

Erin Lee Carr’s writing is filled with tiger-stalking courage. In fact, she writes so well that when she falls off the wagon, you can almost taste the tingling pleasure of her first forbidden sip of cold white wine; how the second and third sips loosen her tightly braided psyche; and then, how the wine slides her into sociability.

“I craved the easy intimacy that came with alcohol,” she writes.

But then, as night follows day, one bottle follows another unto the thundering descent of a drunken abyss. You plummet with her, tumbling to the edge of demon hell when you suddenly freeze and want to scream at her: “No. no. Stop now. Before it’s too late.”

But she can’t turn back. She’s soldered herself to one more bottle that is plunging her into black-out oblivion. As Mark Twain said, “Too much of anything is bad, but too much good whiskey is barely enough.” For alcoholics, Twain’s humor is a shattering truth.

As a millennial writing a memoir, Erin Lee Carr sits at her father’s desk, “hoping some magical transference will take place and I’ll be gifted, if only for a moment, with his way with words.” The magic worked. She’s more than gifted, and she writes beyond her years — yet frequently shows the charm of her youth.

She refers to “my newish boyfriend,” and comments, “I felt instantly crushy toward Bryan,” and marvels about how “I rocked a Rolling Stone t-shirt.” She admits, “I tend to crowdsource everything,” and, about her career as a documentary-film maker, says, “I’m very much grooving along in that path.”

One wishes the best for this talented young woman who almost lost her moorings when her father died, but who, instead, turned her grief inside out to write a gift-giving book about survival — one day at a time.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

L.E.L.

by Kitty Kelley

L.E.L.: The Lost Life and Scandalous Death of Letitia Elizabeth Landon, the Celebrated “Female Byron” is the titillating title of Lucasta Miller’s biography of a 19th-century poet few people remember, if they’d ever heard of her. The title teases, as does the scarlet banner on the cover once used for X-rated magazines sold under the counter.

L.E.L.: The Lost Life and Scandalous Death of Letitia Elizabeth Landon, the Celebrated “Female Byron” is the titillating title of Lucasta Miller’s biography of a 19th-century poet few people remember, if they’d ever heard of her. The title teases, as does the scarlet banner on the cover once used for X-rated magazines sold under the counter.

The cover features a gauzy sketch of a sweet-faced young woman with old eyes and rosebud lips that barely smile. Her long, brown hair is swept up into an intricate arrangement of silken folds and a braid that, if unloosened, promises to tumble to her waist.

The impression is soft but suggestive. In fact, if the book did not carry the august imprint of Knopf, you might expect a Harlequin romance novel. The book cover introduces the life story of an unfortunate woman with talent born in an unfortunate time when, as she wrote:

“None among us dares to say

What none will choose to hear.”

Women of her era dared not put themselves forward on an equal footing with men and appear unladylike. So, to circumvent the strictures of society, many female writers used male pseudonyms to get published: George Sand (Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin), George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans), and Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell (the Brontë sisters — Charlotte, Emily, and Anne, respectively, who preserved their initials). Even Louisa May Alcott wrote her dark love stories under the name of A.M. Barnard.

Letitia Elizabeth Landon became L.E.L. and, as such, she published novels, criticism, and reams of poetry, becoming the toast of literary London.

To ensure her success, she hitched her bright star to a male mentor, the married editor of the Literary Gazette, who published her poetry and paid her a pittance. He promoted her career, reveled in her celebrity, and became her lover, at one point moving her into his home with his wife and children.

Letitia bore him three children, all of whom had to be given up for adoption, such were the mores of the time for an unmarried woman. L.E.L.’s affair with the libertine editor remained secret until 1826, when the Sunday Times published a story headlined “Sapphics and Erotics,” and quoted the editor’s charwoman, who recounted in explicit detail seeing the adulterous couple “in flagrante.”

Author Miller, a British literary critic, contends the reason most people have never heard of L.E.L. is because she was ahead of her time and, not to put too fine a point, was “a fallen woman” whose life was considered so scandalous that her friends tried to shield her from her own infamy.

L.E.L. poured her life into her poems and, after the Times’ exposé, the public read them as confessionals of lust, love, and shame. Her flowery verses dwelled on gothic death, breathless passion, and unrequited love, all a part of her sad existence.

Others suggest that L.E.L.’s talents were more limited than those of Byron, Shelley, and Keats, her male contemporaries, and, thus, didn’t deserve their posterity. Some scholars maintain that L.E.L. got lost in “the strange pause” between the Romantic Age of Byron and the pre-Victorian era of Dickens, who ridiculed L.E.L.’s literary salons and her “rickety sentimental poetry” in The Pickwick Papers.

In her acknowledgements, Miller states that she spent nine years “entangled on and off” in researching and writing this book. The extensive research shows, but so does the entanglement in writing that is dense and academic.

Throughout, she sprinkles her prose with droplets of French: au fait, raison d’etre, cri de couer, de rigueur, cordon sanitaire, femme libre, succes de scandale. After plowing through 320 pages of small type, plus 54 pages of notes and bibliography, one wonders if the author was trying to refashion her Ph.D. thesis for the commercial market.

Like a student bewitched by her research, Miller provides every exhaustive detail about L.E.L. and her lovers, friends, neighbors, and, in one section, a farflung Irish relative, whose “most significant love affair was with the French courtesan-actress Hyacinthe Varis, which produced an illegitimate daughter, Hyacinthe-Gabrielle Roland, who also appeared on the stage, before becoming the mistress of the Duke of Wellington’s brother, the Earl of Mornington.”

Whew.

Miller then bangs on about L.E.L.’s abandoned children, dependent clergyman brother, envious contemporaries (all men), cowardly first fiancé, who bailed on account of the Times story, and the Pygmalion editor who traded her in for a teenage Galatea.

No wonder poor L.E.L., having been exiled from London society and living her last few weeks with an abusive, slave-trading husband on the coast of West Africa, swallowed poison at the age of 36 to end her misery. And ours.

Merde!

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Conversations with Abner Mikva

by Kitty Kelley

The Land of Lincoln has produced giant oaks in the political forest, none more majestic than Abraham himself. But other impressive Illinois timbers have continued to flourish throughout the years: Governor and U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson; Senator Paul Douglas; Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg, also secretary of labor and U.N. ambassador; President Barack Obama; Senator Dick Durbin; and the man fondly referred to in this book as “Ab.”

The Land of Lincoln has produced giant oaks in the political forest, none more majestic than Abraham himself. But other impressive Illinois timbers have continued to flourish throughout the years: Governor and U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson; Senator Paul Douglas; Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg, also secretary of labor and U.N. ambassador; President Barack Obama; Senator Dick Durbin; and the man fondly referred to in this book as “Ab.”

For those lucky enough to have known Abner Mikva during his long and productive life — Illinois State House (1959-1969), U.S. House of Representatives (1969-1973 and 1975-1979), U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia (1979-1994), and White House counsel to President Bill Clinton (1994-1995) — Conversations with Abner Mikva: Final Reflections on Chicago Politics, Democracy’s Future, and a Life of Public Service by Sanford D. Horwitt will be a treasure.

And for those who never knew Mikva but welcome a dose of progressive grace and political grit, it will be a sterling reminder of what public service once looked like, when integrity was the coin of the realm.

During the last three years of his life, Mikva, who served in all three branches of the federal government, met monthly with Horwitt, his good friend and former speechwriter, to reflect on the life he had lived at the center of power. Horwitt’s smart questions and Mikva’s unvarnished answers provide an incisive primer on politics, particularly the chapter dealing with Mikva’s nomination to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, when he was targeted by the National Rifle Association (NRA).

Having been an advocate for gun control all his life, and a sponsor of legislation calling for a ban on the manufacture, importation, and sale of handguns (except for police, military, and licensed pistol clubs), Ab was anathema to the gun lobby, which distributed sporting charts for rifle practice with a bull’s-eye in the middle of Mikva’s face.

The behind-the-scenes story of how he defeated the NRA to be confirmed by the Senate should be a master class in political science. Although he was confirmed 58-31, he never forgave the NRA Democrats, all afraid of the NRA, who voted against him.

Being from Chicago, Mikva was not naive about political corruption, which is why he took such a hard line on white-collar crime and felt it should be punished with time behind bars, not simply huge fines. “If we’re going to have jails it makes much more sense to use them for white collar crime. That’s where the punishment angle, the humbling angle” comes in.

He found the case of Virginia’s former Republican governor Robert F. McDonnell to be particularly egregious, and felt that McDonnell, who was found guilty by a federal jury of political corruption for accepting lavish gifts, including a $6,000 Rolex, “should get at least five years” in prison, “and as far as I’m concerned, ten would be a good number.” McDonnell was sentenced to two years but appealed his case to the Supreme Court, which unanimously vacated the conviction.

The subject of white-collar crime led to conversations about the subprime mortgage disaster of 2008, when no senior executive from Wall Street or any of the big banks was put on trial. Here, Mikva chides Obama’s Justice Department under Attorney General Eric Holder:

“[W]hen it came to civil justice, as far as [Holder] was concerned, you don’t send white-collar criminals to jail. That’s not nice…They don’t do things like that at Covington & Burling [Holder’s law firm], a white shoe firm where the notion of sending executives to jail was unheard of.”

Nor does he hold back on his old friend Barack Obama, with whom he campaigned in 2000 when Obama made his first run for political office and lost:

“He was…dreadful on the stump. I went with him to several places. One was a black church, and he was awful. He was a dull University of Chicago professor lecturing the unwashed, who couldn’t be less interested…But he realized out of that very disheartening loss that you’ve got to show them, you’ve got to be a showman. Boy, did he learn.”

Mikva gives the young man he mentored “a low A” as president and feels Obama will go down in history as one of the greats.

President Bill Clinton does not get the same high marks from his former White House counsel, who was disappointed when “Slick Willie” interrupted his presidential campaign to fly to Arkansas to sign execution orders for a mentally incapacitated man:

“Clinton did exactly the wrong thing. He should have kept that guy from being executed. He was for capital punishment, or so he said. The real Bill Clinton is not for capital punishment. He thought that was a political necessity in Arkansas.”

Mikva also faults Clinton’s support of habeas corpus, prayer in public schools, and the amendment to prohibit flag-burning. “His instincts were to stay with God…He had been educated on the separation of church and state at Yale and Oxford, but those weren’t his views. On these God and flag issues he was Arkansas through and through.”

In 2014, President Obama gave his mentor the Presidential Medal of Freedom, an honor Mikva shared that day with, among others, Meryl Streep, Tom Brokaw, and, posthumously, the three civil rights workers who were murdered in 1964 — James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner. “They got the most sustained applause,” said Mikva. “They deserved it.”

Abner Mikva, who died on the Fourth of July in 2016 at age 90, had a worthy Boswell in Sanford Horwitt, and both deserve a standing ovation for this book — a superbly written history of a man who believed in public service and practiced it, becoming a hero to many.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Becoming

by Kitty Kelley

A few months ago, Michelle Obama zoomed to the top of the bestseller list with Becoming, and set the gold standard for writing a masterful memoir. As wife of the nation’s first African-American president, she has an extraordinary story to tell, and she tells it with sublime grace, substance, and style.

A few months ago, Michelle Obama zoomed to the top of the bestseller list with Becoming, and set the gold standard for writing a masterful memoir. As wife of the nation’s first African-American president, she has an extraordinary story to tell, and she tells it with sublime grace, substance, and style.

In reading it, you’ll understand why she is packing auditoriums around the world, selling out huge venues like the Royal Arena in Denmark, the Oslo Spektrum, Amsterdam’s Ziggo Dome, and the AccorHotels Arena in Paris. In civic auditoriums around the U.S., people beg to pay upward of $1,000 a ticket to hear the most powerful African-American woman in the world tell her story.

In the book, Obama addresses her most controversial moment in the 2008 presidential campaign when she said that “for the first time in my adult life I’m really proud of my country.” At the time, she was criticized for the comment by those who felt she sounded like an angry black woman who was unpatriotic. She writes that she meant nothing racial by her words, merely that she was expressing gratitude for the many energetic campaign workers.

Days after the book’s publication, she got criticized again, this time in a New York Times op-ed by a black female professor from Antioch University who urged Obama to own the full weight of her words from 2008 and broaden the narrative to discuss black discontent.

Many will find Becoming to be a heartfelt dissertation on race, and the White House is a perfect setting for Michelle Robinson Obama’s story because she’s more closely tied to the site than any of her predecessors. She frequently introduces herself to young African-American audiences as the great-great-granddaughter of Jim Robinson, a slave from South Carolina. Enslaved people, like her own ancestors, built the mansion, which has housed 44 white presidents, several of whom owned slaves.

She knows she carries history with her, but it’s not the history of presidents and other first ladies:

“I’d never related to the story of John Quincy Adams the way I did to that of Sojourner Truth, or been moved by Woodrow Wilson the way I was by Harriet Tubman. The struggles of Rosa Parks and Coretta Scott King were more familiar to me than those of Eleanor Roosevelt or Mamie Eisenhower.”

Obama writes about growing up as an urban black child on the South Side of Chicago, always feeling “other.” She relates an incident when she and her brother were children that taught them “the color of our skin made us vulnerable [to attack]. It was a thing we’d always have to navigate.” Throughout the book, she underscores race and the constant vigilance people of color feel forced to bring to their encounters in white America.

She emphasizes her roots in a close-knit, working-class family, where her parents knew that education was the best way up and out. But while Michelle Robinson soared up — graduating from Princeton and Harvard Law School — she never flew out. She remained committed to her city and chides Maureen Dowd for calling her “a princess of South Chicago” in the New York Times.

As first lady, she tried to rally support for violence prevention there, meeting often with community leaders and social workers in the inner city. Yet she leveled with students from the ravaged area: “Honestly, I know you’re dealing with a lot here, but no one’s going to save you anytime soon.”

She told them the only way out of their mess was to “use school” as she had. She saw herself as a testament to what was possible. “I felt it all personally. Education had been the primary instrument of change in my own life, my lever upward in the world….”

Ever since Jacqueline Kennedy restored the public rooms of the White House, all first ladies have been expected to have a high-purpose project, preferably apolitical and certainly not controversial. Lady Bird Johnson beautified America with trees and flowers; Pat Nixon chose volunteerism; Betty Ford supported the Equal Rights Amendment; Rosalynn Carter promoted mental-health awareness; Nancy Reagan launched “Just Say No” to drugs; Barbara Bush concentrated on literacy; Hillary Clinton undertook healthcare reform; Laura Bush advocated for childhood education; and Michelle Obama planted a vegetable garden.

Since African-American children are more likely to be overweight than their white counterparts, the former first lady, who works out regularly, launched “Let’s Move,” and, with an emphasis on eating more nutritiously, was determined to end childhood obesity within a generation.

Yet even this worthy objective drew partisan criticism. Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner (R-Wis.) complained to his constituents about Obama lecturing about obesity with “her big butt.” The congressman, who looks to be the size of a food truck, later wrote a note apologizing to the first lady for commenting on her “large posterior.” Still, she felt mocked.

“I was cut down for being black, female and vocal. I’d felt the derision directed at my body, the literal space I occupied in the world.”

She wallops Donald Trump for his “yammering, inexpert critiques of Barack’s foreign policy decisions and openly questioning whether he was an American citizen…with his loud and reckless innuendos he was putting my family’s safety at risk. And for this, I’d never forgive him.”

Having been advised by Hillary Clinton never to get in front of the president, Obama went to great lengths not to insert herself into West Wing business — to such an absurd extent that her staff felt it was necessary to consult with the president’s staff when she “decided to get bangs cut into my hair…just to make sure there wouldn’t be a problem.”

Seriously?

She captures the essence of her husband’s sterling idealism when she quotes him as saying, “You may live in the world as it is, but you can still work to create the world as it should be.” She was understandably angry when Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) declared a year before the 2011 election: “The single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term president.”

She writes that her husband took the high road, reminding her of “an old copper pot — seasoned by fire, dinged up but still shiny.”

Michelle Obama shines, too, in a most becoming way.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Doing Justice

by Kitty Kelley

With Doing Justice: A Prosecutor’s Thoughts on Crime, Punishment, and the Rule of Law, Preet Bharara writes himself into the diamond circle of Clarence Darrow. There have been other good books by lawyers — including Louis Nizer’s My Life in Court and One Man’s Freedom by Edward Bennett Williams — that have enriched our understanding of the law and its application by practitioners of the bar. But Darrow set the gold standard in 1932 with The Story of My Life, which recounts one of the most extraordinary legal careers in American history.

With Doing Justice: A Prosecutor’s Thoughts on Crime, Punishment, and the Rule of Law, Preet Bharara writes himself into the diamond circle of Clarence Darrow. There have been other good books by lawyers — including Louis Nizer’s My Life in Court and One Man’s Freedom by Edward Bennett Williams — that have enriched our understanding of the law and its application by practitioners of the bar. But Darrow set the gold standard in 1932 with The Story of My Life, which recounts one of the most extraordinary legal careers in American history.

In recent years, we’ve had to turn to the fiction of John Grisham (The Firm, The Client, The Pelican Brief, etc.) and the work of Aaron Sorkin (including his Broadway adaptations of “A Few Good Men” and To Kill a Mockingbird) to appreciate the vexing complexities that challenge doing justice.

But now we have an un-put-down-able primer from the former U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York (SDNY), written with immense skill and engaging style. He’s tough, smart, and funny. He does not condescend to readers without legal credentials but clearly explains what “confirmation bias” is, what “proffers” are, and why most trial lawyers won’t risk irritating judges with “a motion for reconsideration.”

He tells riveting stories from real-life experience and attributes his near-perfect record as a federal prosecutor to the hard work and preparation that his team invested in achieving convictions in cases such as the Madoff/JPMorgan Chase Ponzi scheme and a scam defrauding a fund for Holocaust survivors.

Impressive is Bharara’s professional generosity. He dedicates his book to the “fearless women and men of the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York” and, throughout its pages, he cites those who helped him achieve enormous success, naming numerous attorneys, as well as investigators and police detectives.

He wins admiration when he admits error. “We did not always get it right…we pursued cases that some people thought were overreach, and we walked away from others that some were dying to see us bring.”

In 2012, Bharara made the cover of Time with the headline: “This Man is Busting Wall Street.” Yet some critics, like William D. Cohan in the Nation and Jesse Eisinger, author of the 2017 book The Chickenshit Club: Why the Justice Department Fails to Prosecute Executives, fault him for not indicting anyone after the 2008 financial crisis.

Bharara addresses the “odious conduct” by Wall Street thugs, writing: “No one likes the fact that bad actors got away with harming many innocent people,” but “we can only bring cases when the facts and the law lend support to an indictment.”

He prosecuted gangs, banks, drug lords, insider traders, arms traffickers, Russian money launderers, and “the epidemic of corruption in Albany.” In a chapter entitled “Three Men in a Room,” he draws a shady picture of New York governor Andrew Cuomo, State Assembly speaker Sheldon Silver, and State Senate majority leader Dean Skelos:

“Power in New York state is unduly concentrated in the hands of…just 3 men…who famously made all important decisions for the people of New York, mostly behind closed doors.”

He convicted two of the three and regrets not being able to wrestle the law into a choke-hold on the governor. “I have a lot I could say about the people we did not charge, after lengthy investigations. But I won’t. It is what it is.”

The SDNY is frequently referred to as the “Sovereign District” or the “Mother Church” because of its sterling record of criminal prosecutions. The New York Times calls it “one of New York City’s most powerful clubs,” because, as Bharara explains, its lawyers “are among the best-educated, most credentialed, highest achieving young lawyers in the country. Many clerk for the Supreme Court and are at the top of their class at the most prestigious schools.” Even he admits to having been intimidated by some of the résumés that crossed his desk.

But Bharara’s bona fides bow to none: Valedictorian of his high school, he graduated from Harvard and Columbia Law School, where he was a member of the Columbia Law Review. After several years in private practice doing white-collar defense work, Bharara served as chief counsel to Senator Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and was appointed by President Obama to be U.S. attorney for the SDNY, which, he writes, is “the best place I will ever work.” He held the position from 2009 to 2017 and racked up numerous convictions.

Following the 2016 presidential election, Donald Trump asked him to remain in his position, which gave him prosecutorial jurisdiction over many parts of Trump’s business empire. Seven weeks after the inauguration, Trump wanted him to resign. Bharara refused and was fired.

He later said on his podcast, “Stay Tuned with Preet,” that he believed the president would have asked him “to do something inappropriate” if he had stayed longer in the job. He joined New York University School of Law as distinguished scholar in residence, but he seems destined for broader horizons. Maybe Senator Preet? Possibly Governor Bharara?

Preet Bharara writes that you will not find God or grace in legal concepts or in formal notions of criminal justice. But be assured that you’ll find God and grace in this fascinating book.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books