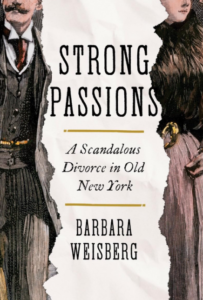

Strong Passions

by Kitty Kelley

The title of this book is a clever double entendre. Strong Passions refers to the scandalous divorce of a 19th-century couple named Strong, whose ruptured marriage scars their families and sears their social standing. The first few pages offer a who’s who of high society à la Edith Wharton. In fact, Barbara Weisberg introduces her narrative by quoting from Wharton’s short story “A Cup of Cold Water,” tantalizing readers with the promise of prose from the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction (in 1921, for The Age of Innocence).

The title of this book is a clever double entendre. Strong Passions refers to the scandalous divorce of a 19th-century couple named Strong, whose ruptured marriage scars their families and sears their social standing. The first few pages offer a who’s who of high society à la Edith Wharton. In fact, Barbara Weisberg introduces her narrative by quoting from Wharton’s short story “A Cup of Cold Water,” tantalizing readers with the promise of prose from the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction (in 1921, for The Age of Innocence).

Caveat emptor: Wharton’s only connection to the story told in this book is that she is 2 years old and living in New York City at the time the marital travesty unfolds between Peter Remsen Strong and Mary Emeline Stevens Strong.

The first part of this melodrama reads like a social history of the mid-1800s, when travel by ship from New York to Le Havre took three weeks, and “gentlemen” of a certain class enjoyed gambling houses, cafes, and bordellos while a few — very few — “ladies” traveled abroad. (And when they did, they were always chaperoned and shopped in Paris for “fabulous wardrobes.”)

Such details anchor the story in its era, but without much access to diaries, journals, or letters, Weisberg tells her tale in unsatisfying hypotheticals: “[Mary] would have imagined herself in the roles of wife and mother”; “She might have been eager to hear”; “Her wedding night surely was revelatory”; “Her activities…in an affluent household most likely included”; “She most likely feared.”

Weisberg, whose first book was Talking to the Dead: Kate and Maggie Fox and the Rise of Spiritualism, informs readers in this work that breastfeeding reduced the chance of pregnancy and was considered in the 19th century a form of birth control, which, the author “supposes,” is why Mary refused to wean her third daughter a few months after she was born. That baby, Edith, dies of influenza at 14 months old. On the day of the baby’s funeral, Mary, in a distraught state, admits to her husband that she’d been having an affair with his widowed brother, Edward, who conveniently enlists to fight for the Union in the Civil War. Oh, and P.S.: Mary is five months pregnant, but neither she nor Peter knows by whom.

Determined to salvage his marriage, Peter insists that his wife terminate the pregnancy. To do so, he visits his “alleged” mistress, who happens to be a “mid-wife” renting one of his properties on Waverly Place, where she advertises herself as a “woman doctor.” The author explains this is “a euphemism for a woman who did abortions.” Readers are then treated to several pages on abortion in the 1800s, as well as on adultery, the only basis for divorce in New York until 1922.

Pages later, Peter moves back to his mother’s estate in Newtown, Queens, with his elder daughter, Mamie, and sues his wife for divorce on grounds of adultery. Mary counter-sues, claiming her husband forced her to have an abortion at the hands of an abortionist with whom he was having an affair. Mary then runs away with their younger daughter, Allie. The scoundrel brother of the humiliated husband remains at war, safe from the drama.

Weisberg has presented a legitimate scandal by 19th-century standards: adultery, abortion, and abduction. “Because of the social relations and the position of the parties, and the singular charges and counter charges,” reported the New York Times, “no case before our courts for many years has attracted greater attention.”

Unfortunately, the story becomes more tabloid pottage than Wharton-esque prose. An appropriate comparison might be Mark Twain’s definition of “the difference between the almost right word and the right word” as the difference between a lightning bug and lightning.

Without conclusive evidence of what happened, the author, like the 19th-century journalists covering the case, had more questions than answers: “Where was Mary? Had she kept her little one safe? Had she indeed committed the dreadful offenses of which she was accused? Was she a victim? A seductress?” And where was the errant brother, Edward, in this “near-biblical tale of fraternal betrayal”?

After a six-week trial — the author devotes a dense, detail-laden chapter to each week — the reader is exhausted. The jury does not reach a unanimous verdict, and so Mary, who never appears in court, remains Peter’s lawfully wedded wife. At this point, patience expires, along with sympathy for either party — the wronged husband seeking revenge and the adulterous wife who escapes with her younger child.

Months later, Mary’s attorneys sue for lawyers’ fees and alimony, and the court rules in her favor. Then, in a magnanimous change of heart, Peter, “desirous of…avoiding the scandal of a second public trial,” petitions the court to provide tuition and other money to care for Allie until her 18th birthday. After six years, the divorce is finalized. Peter resumes his life as a gentleman of society, while Mary, ostracized by that society, remains in France with her daughter.

Weisberg insists in her afterword that Strong v. Strong is relevant social history, and on that point, she may be correct. But her attempt to weave the Civil War, the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the Constitution, and the 1868 impeachment of President Andrew Johnson into her protracted narrative proves to be “more lightning bug than lightning.”

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books