The Counterfeit Countess

by Kitty Kelley

I approach Holocaust memoirs with knee-bending respect: for the survivors who recall the atrocities they suffered during World War II so that we will never forget, and for the historians who document man’s inhumanity to man. In The Counterfeit Countess, Elizabeth B. White and Joanna Sliwa tell the story of a Polish mathematics professor who hid her identity as Janina Mehlberg (nee Pepi Spinner) when she fled the Jewish ghetto of Lwów, Poland, and reinvented herself as Countess Janina Suchodolska hundreds of miles away in Lublin, where she saved thousands of fellow Jews from annihilation.

I approach Holocaust memoirs with knee-bending respect: for the survivors who recall the atrocities they suffered during World War II so that we will never forget, and for the historians who document man’s inhumanity to man. In The Counterfeit Countess, Elizabeth B. White and Joanna Sliwa tell the story of a Polish mathematics professor who hid her identity as Janina Mehlberg (nee Pepi Spinner) when she fled the Jewish ghetto of Lwów, Poland, and reinvented herself as Countess Janina Suchodolska hundreds of miles away in Lublin, where she saved thousands of fellow Jews from annihilation.

Lublin was headquarters of Aktion Reinhard, the largest SS mass-murder operation of the Holocaust, during which 1.7 million Jews in Poland were slaughtered. German-occupied Poland was effectively ground zero for Hitler’s “final solution”; the place where the majority of the war’s Jewish victims perished; and home to some of the Third Reich’s most notorious concentration camps, including Auschwitz, Chelmno, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, and Majdanek. The latter, with its seven gas chambers, two wooden gallows, crematorium, and 227 outbuildings, was among the largest of Poland’s extermination factories — holding 250,000 prisoners — and is the focus of this book.

The authors are unsparing in describing the unrelenting and unrelieved miseries inflicted by the Nazis in decimating the Jewish population of Poland, which had the largest concentration of Jews in Europe in 1939 — 3.5 million then, fewer than 20,000 today. It becomes almost numbing to read of the killing of so many Jews, Roma (gypsies), and others at the hands of the Germans and their minions.

Nor do the authors spare the survivors, including the countess and her husband, also a professor, who abandoned their Jewish family and friends and assumed new identities as Polish Christian aristocrats in order to escape the Nazis’ brutal plans. The countess understood the animal-like desperation of humans to survive, but it’s only at the end of the book that the authors share excerpts from her unpublished memoir, in which she writes:

“What would a mother do in the face of the impossible choices put to her? There was one who, with her daughter, hid in the wardrobes of her apartment during a raid. They found her daughter, but not her. The child sobbed and screamed for her mother to save her. The mother kept silent, and survived. I know this from the mother herself who, sobbing out her story, wished herself dead instead of condemned to live with this memory.

“Another mother hid with her son in a bunker…Her son ventured out at the wrong time; he was seized and shot right there. The mother heard and remained silent.”

The countess withholds judgment on these impulses to survive, “however grim and unbearable the knowledge may be…Because while physical and psychic tortures broke many, some reacted with what one can only call moral grandeur. I know some…who helped their fellow sufferers at the cost of their own lives, who confessed to others’ ‘crimes,’ who willingly chose death over a degrading life. So, the murder of goodness was not thorough, and this fact, too, must be reported.”

The voice of the countess is so powerful that one wishes the academic co-authors, accomplished as they may be in assembling statistics and geographical details, had allowed her to tell the story in her own words, and then, perhaps, buttressed her account with their prodigious research from Holocaust museums and libraries in the U.S., Canada, Argentina, Uruguay, Germany, and Poland. Although the countess’ memoir concentrates only on what she saw and learned about human nature within the terrible crucible of occupied Poland, her words, her thoughts, and her recollections are enough to lead her story.

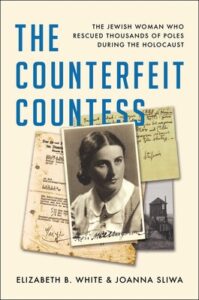

A small, cropped photo on the cover of the book shows the countess as a young woman with dark, shiny hair parted in the middle and pulled tightly back behind her ears in the era’s fashionable buns. Yet her biographers barely mention her appearance until 200 pages in, when they quote someone describing her as “small, dark and bright-eyed with massive braids of black hair wound round her head.”

Only in the epilogue do we get her husband’s description of her as “more than ordinarily pretty, very feminine in her style.” Aha. Now we understand how the countess — with her imposing title and good looks — was able to entice so many Nazi guards into waving her through concentration-camp gates without always examining the truckloads of food and collapsible milk urns stuffed with contraband medicine she was delivering to prisoners.

After the war, she returned to her roots as mathematician Josephine Janina Bednarski Spinner Mehlberg and immigrated to Canada with her husband. In 1961, they moved to the U.S. and became American citizens. Before “the counterfeit countess” died in 1969, she returned to Majdanek, writing in her memoir:

“I had achieved less than I had hoped, but I tried, and my efforts had made a difference, so my life had made some difference…Then I thought of those who had been broken, physically and morally, who had betrayed other lives in the hope of saving their own. Of them I spoke…None of us has the right to sit in judgment on them…There is nothing left to do for them but to remember. And in the way of my ancestors intone ‘Yisgadal, v’yiskadash,’ the Kaddish for the dead, and like the real Countess Suchodolska, ‘Kyrie Eleison, Christe Eleison.’ We will remember.”

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books