Undelivered

by Kitty Kelley

“For all sad words of tongue and pen,

The saddest are these, ‘It might have been.’”

These woeful words from Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier might apply to politicians and lovers and horses who’ve never made the winner’s circle. Those losses are particularly painful for politicians who are expected to concede gracefully and congratulate the fiend who just walloped them. As Rep. Morris Udall said after losing the 1976 Democratic nomination for president, “It’d be less painful to get mowed down by an 18-wheeler.”

These woeful words from Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier might apply to politicians and lovers and horses who’ve never made the winner’s circle. Those losses are particularly painful for politicians who are expected to concede gracefully and congratulate the fiend who just walloped them. As Rep. Morris Udall said after losing the 1976 Democratic nomination for president, “It’d be less painful to get mowed down by an 18-wheeler.”

Hillary Clinton felt the same way in 2016 after winning the popular vote for president by over 4 million votes but losing the Electoral College by 306-232, and thus the presidency. The former secretary of state/U.S. senator/first lady was poised to claim victory with prepared remarks thanking “my fellow Americans” for “reaching for unity, decency and what President Lincoln called ‘the better angels of our nature.’”

But those better angels flew away as Clinton acknowledged her loss to Donald J. Trump with civility and just a  couple of tears. After thanking her family, staff, volunteers, and contributors, she apologized to them, becoming the first presidential candidate in history to say “I’m sorry” in a concession speech.

couple of tears. After thanking her family, staff, volunteers, and contributors, she apologized to them, becoming the first presidential candidate in history to say “I’m sorry” in a concession speech.

Now we’re finding out what Clinton would’ve said as president-elect had she won the campaign that cost over $581 million. Her six-page victory speech, never given, is reported in full by Jeff Nussbaum in his creative new book, Undelivered: The Never-Heard Speeches that Would Have Rewritten History.

Some of the unspoken speeches unearthed by Nussbaum’s dogged research and informative text spark jump-up-and-down joy, particularly those in the section entitled “The Fog of War, The Path to Peace.” Each of its three segments is noteworthy, beginning with the words of apology General Dwight D. Eisenhower would’ve delivered if the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944, had failed.

“The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do,” he wrote in a brief, four-sentence statement. “If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone.” Nussbaum, a speechwriter for Democrats, recognizes Eisenhower’s words as “an object lesson in the language of leadership and responsibility.”

Knowing that “victory has a hundred fathers and defeat is an orphan,” President John F. Kennedy prepared a never-delivered speech to the nation in 1962 to announce airstrikes on Cuba “to remove a major nuclear weapons build up.” The president had gathered his top cabinet officers — hawks and doves alike — to debate the issue and discuss what to do.

“Each one of us was being asked to make a recommendation which would affect the future of all mankind,” wrote Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy of the Cuban Missile Crisis, “a recommendation which, if wrong and if accepted, could mean the destruction of the human race.” For 13 days, the U.S. teetered on the edge of war with the Soviet Union, until Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev blinked and removed his missiles.

The third example of an undelivered speech that might’ve changed history is Emperor Hirohito’s apology for Japan’s role in World War II, which he wrote in 1948, lamenting the “countless corpses…[left]…on the battlefield [and] the countless people [who] lost their lives…Our heart is seared with grief. We are deeply ashamed…for our lack of virtue.”

Now to the bits that don’t stir jump-up-and-down joy. Much of Nussbaum’s book reads like a garrulous guy on a binge while his editor is A.W.O.L. The author meanders back and forth from a third-person narrative to first-person asides, political anecdotes, pesky footnotes, and lame jokes (see the one about St. Peter and speechwriters). He jams his book to the brim with historical information, proving that he’s read widely, and is hellbent on sharing every bit of his findings, which he piles into 374 pages of main text, 38 pages of notes, a 30-page bibliography, and a 28-page appendix. (Dear Santa: Please put a copy of Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style in Nussbaum’s Christmas stocking.)

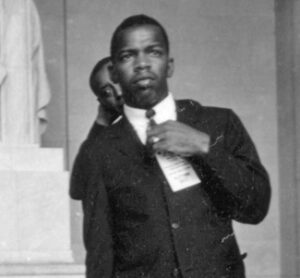

An example of what might be described as logorrhea begins in the first chapter and deals with late congressman John Lewis’ proposed speech at the 1963 March on Washington. Lewis’ original remarks were deemed too fiery for Archbishop Patrick O’Boyle, who refused to make the morning’s invocation if Lewis didn’t tone down his rhetoric. March organizers pressured Lewis, saying that without the Irish Catholic prelate, they might lose support from the Irish Catholic president, which would influence Congress and doom Civil Rights legislation. So, Lewis compromised.

An example of what might be described as logorrhea begins in the first chapter and deals with late congressman John Lewis’ proposed speech at the 1963 March on Washington. Lewis’ original remarks were deemed too fiery for Archbishop Patrick O’Boyle, who refused to make the morning’s invocation if Lewis didn’t tone down his rhetoric. March organizers pressured Lewis, saying that without the Irish Catholic prelate, they might lose support from the Irish Catholic president, which would influence Congress and doom Civil Rights legislation. So, Lewis compromised.

At this point, the author-in-need-of-an-editor interrupts his story of Lewis’ speech to relate his own stories of being a speechwriter at the Democratic National Convention from 2000 through 2020. He rambles on about Melania Trump, who lifted from Michelle Obama’s speech, Al Sharpton’s refusal to use a teleprompter, and Barney Frank’s speech impediment, and includes brief mentions of 2012 Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney, his wife, Anne, and the GOP convention’s keynote speaker, New Jersey governor Chris Christie. (P.S. to Santa: Please add Arthur Plotnik’s Spunk & Bite: A Writer’s Guide to Bold, Contemporary Style to that stocking.)

Eventually, Nussbaum circles back to the dilemma facing Lewis, but only for a few pages before he interrupts the narrative again with more reflections on his own speechwriting. Then, and only then (thank you, Jesus), does he return to finish the story of Lewis and his 1963 speech.

Note to readers: Lewis’ undelivered speech is just the book’s first chapter. You’ve got 14 more to go. (P.P.S. to Santa: Forget your sleigh. Use FedEx.)

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

(Photos: John Lewis at the Lincoln Memorial, 1963 © Estate of Stanley Tretick; Hillary Clinton conceding, 2016, PBS/YouTube)