Pride of Family

by Kitty Kelley

Carole Ione grew up in a world of beautiful Black women of various shades, where marriages crumbled, fathers fell by the wayside, and mothers forged ahead with careers and the “occasional” man. As a 10-year-old sitting at the piano listening to her mother sing Calypso songs, Ione, as she now calls herself, “learned early on from those lyrics that soldiers and sailors could be trouble — you might never see them again.”

Carole Ione grew up in a world of beautiful Black women of various shades, where marriages crumbled, fathers fell by the wayside, and mothers forged ahead with careers and the “occasional” man. As a 10-year-old sitting at the piano listening to her mother sing Calypso songs, Ione, as she now calls herself, “learned early on from those lyrics that soldiers and sailors could be trouble — you might never see them again.”

Ione’s only paladins were women: her great-aunt, Sistonie, a physician and member of Washington’s Black aristocracy; her grandmother, Be-Be, a former Broadway chorus dancer who ran the best restaurant in Saratoga Springs, drawing celebrities like Cab Calloway, Paul Robeson, Josephine Baker, and Ethel Waters; and her mother, Leighla, who carved a career writing mysteries. Ironically, the biggest mystery hid behind the stone wall of secrets that kept the women estranged and incapable of bonding as a family.

At the age of 19, against fierce objections, Ione married a white Frenchman. In 1956, they moved to his home in Alsace, where everyone in the textile-manufacturing town was white and spoke a German dialect called Elsässerditsch. That part of France, the Haut-Rhin, was scorned by Parisians as the exterieur, so its denizens tried to be “more French than the French,” Ione writes. As a Black American woman, she became a freakish curiosity, stared at in the streets:

“I realize now that it was exactly that depressing feeling of being thought inferior to the society I lived in that I had hoped to escape by marrying…[I longed] to assuage the painful and confusing aspects of blackness.”

Soon, she and her husband moved back to New York, where they occupied separate bedrooms and led separate lives as he encouraged a philosophy of free love. Ione began an affair with a married alcoholic man many years her junior, followed by an even more unconventional relationship with a woman painter who lived in a loft on Canal Street:

“I had begun to understand that I was — like most people, I thought — not simply heterosexual but sexual, and from then on I would resist any labels on my sexuality.”

After her divorce, she married “a gay man living as a heterosexual” with whom she had three children. But after 13 years “of no love for me,” she again divorced. Ione received no succor from her mother or grandmother, only a “frosty politeness.” Both blamed her for leaving her husband and becoming like them: a single mother.

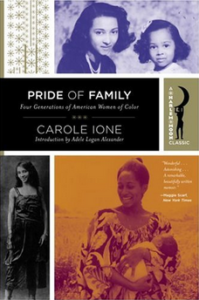

Feeling betrayed and desperate for a sense of belonging, Ione sought to explore the lives of her family, a word she italicizes as if it’s exotic and foreign. The result, published in 1991 when she was 54, was Pride of Family: Four Generations of American Women of Color, a rich reverie of superb writing — half memoir, half biography — nine years in the making that probes the tortured bonds of mothers and daughters and the journey of one girl through a gnarled thicket of secrets.

With bracing honesty and eloquence, Ione documents in Pride of Family the alienation she felt within her own community, where a pernicious line of color had segregated her since childhood:

If you’re white, you’re all right.

If you’re brown, stick around.

If you’re black, get back.

When she found her maternal grandfather late in life, she asked him about his mother, and he said that she, Ione’s great-grandmother, was good-looking. “She was fair. Very light skin — and she had good hair.” That one word — hair — is freighted for Black women, and Ione was particularly sensitive about it as her mother and grandmother were light-skinned beauties with straight, silky hair:

“Mine was fuzzy, woolly, nappy…everything I didn’t want it to be…my hair was bad…not in the worst degrees of ‘bad’ — for there are degrees — but ‘bad’ nonetheless. Did this make my mother and grandmother love me less, did it create a subtle distance between us?”

That distance narrowed when Ione discovered the diary of her great-grandmother, Frances “Frank” Anne Rollin (1845-1902), and unearthed many family secrets. Rollin also gave Ione, a writer, a feeling of pride for her foremother, a 19th-century activist who was the first known African American biographer. In 1868, Rollin wrote The Life and Public Services of Martin R. Delany under the name Frank A. Rollin.

That biography is little known today, but the biographer lives on, having been recently embraced by Biographers International Organization (BIO), which established the Frances “Frank” Rollin Fellowship for African American Biography, providing a $2,000 fellowship for a writer working on a life story of an African American figure or someone whose story provides a significant contribution to the Black experience.

Ione, now 83 and living in Kingston, New York, is thrilled by the fellowship. “It’s a dream coming true through the centuries,” she told BIO. “There was a line in [Frank’s] diary in which she said she wanted to ‘make her mark in literature,’ and now [I feel] it’s finally happened.”

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books