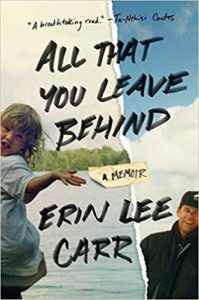

All That You Leave Behind

by Kitty Kelley

“The gods giveth and the gods taketh away.” So goes a biblical tenet from the Book of Job, which Erin Lee Carr confirms in her new book, All That You Leave Behind. With piercing honesty, she writes a dazzling drunk-a-log about her on-again, off-again struggle with sobriety, and examines which genes the gods gave her and which they took away.

“The gods giveth and the gods taketh away.” So goes a biblical tenet from the Book of Job, which Erin Lee Carr confirms in her new book, All That You Leave Behind. With piercing honesty, she writes a dazzling drunk-a-log about her on-again, off-again struggle with sobriety, and examines which genes the gods gave her and which they took away.

Her book is also a love letter to her father, David Carr, who wrote his own addiction memoir, The Night of the Gun, in 2008. He died seven years later at his desk at the New York Times. He was only 58, and his daughter, then 27, was inconsolable. She obviously wrote this book to find a way out of her grief, but even a year later, she writes that she could not bear to be “around women and their fathers.”

Erin was a daddy’s girl because Daddy was the only parent she had, even when he left her and her twin sister in a car in the dead of a Minnesota winter to get high in a crack house. Their mother, still alive and still drug-addicted, has not been in their lives since they were 14.

“Sorry Mom,” Erin writes in her acknowledgements, “I know this is hard for you.”

I came to this book because I admired David Carr’s reportage on film, media, and culture in the Times. I was riveted by his harrowing life story of down-and-out addiction, steel bracelets, and jail cells followed — heroically — by AA recovery, which, coupled with monumental talent, finally rocketed him to success as a journalist.

His daughter tells us it was his raging ambition to write his way to national recognition, and possibly a Pulitzer, that pushed him into the sobriety that finally saved him. The Pulitzer eluded him, but he attracted a huge following on Twitter and died at the crest of an accomplished career.

“Sort of a mic drop, really,” Erin writes. This might not seem like salvation to many but, given Carr’s epic battles with addiction, his five-plus decades on this planet were a triumph over lifespan logic.

David Carr bequeathed his talents and his torments to his daughter, who writes bravely about her struggles with sobriety and bracingly about the father she adored, who once told her: “Looking at you is like looking into a dirty mirror.”

She recalls that the comment stung in the moment and stung again when she wrote it. “It shows that he wanted me to be a mirror image of himself, but was disturbed when it actually looked like him.”

He was her father and mentor, “one relationship always in conflict with the other.” In both roles, he needed her to be successful to be part of his legacy: “You can either be a big deal in your own right or have a drinking problem for the next ten years and be of little significance,” she quotes him as saying. He prided himself on his golden Rolodex filled with famous names, “People I read about in my battered copies of Entertainment Weekly. He liked to name drop.”

Erin Lee Carr’s writing is filled with tiger-stalking courage. In fact, she writes so well that when she falls off the wagon, you can almost taste the tingling pleasure of her first forbidden sip of cold white wine; how the second and third sips loosen her tightly braided psyche; and then, how the wine slides her into sociability.

“I craved the easy intimacy that came with alcohol,” she writes.

But then, as night follows day, one bottle follows another unto the thundering descent of a drunken abyss. You plummet with her, tumbling to the edge of demon hell when you suddenly freeze and want to scream at her: “No. no. Stop now. Before it’s too late.”

But she can’t turn back. She’s soldered herself to one more bottle that is plunging her into black-out oblivion. As Mark Twain said, “Too much of anything is bad, but too much good whiskey is barely enough.” For alcoholics, Twain’s humor is a shattering truth.

As a millennial writing a memoir, Erin Lee Carr sits at her father’s desk, “hoping some magical transference will take place and I’ll be gifted, if only for a moment, with his way with words.” The magic worked. She’s more than gifted, and she writes beyond her years — yet frequently shows the charm of her youth.

She refers to “my newish boyfriend,” and comments, “I felt instantly crushy toward Bryan,” and marvels about how “I rocked a Rolling Stone t-shirt.” She admits, “I tend to crowdsource everything,” and, about her career as a documentary-film maker, says, “I’m very much grooving along in that path.”

One wishes the best for this talented young woman who almost lost her moorings when her father died, but who, instead, turned her grief inside out to write a gift-giving book about survival — one day at a time.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books