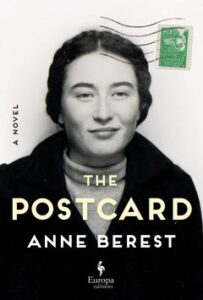

The Postcard

by Kitty Kelley

An “un-put-down-able” book is like a double rainbow — rare and oh so magical. Titles like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles, Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter, The Godfather by Mario Puzo, The Thorn Birds by Colleen McCullough, Strange Fruit by Lillian Smith, and The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton are just a few such double rainbows that stir the soul much like the spine-tingling stories of Stephen King, John le Carré’s Cold War spy thrillers, and the works of Walt Whitman, America’s poet emeritus.

An “un-put-down-able” book is like a double rainbow — rare and oh so magical. Titles like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles, Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter, The Godfather by Mario Puzo, The Thorn Birds by Colleen McCullough, Strange Fruit by Lillian Smith, and The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton are just a few such double rainbows that stir the soul much like the spine-tingling stories of Stephen King, John le Carré’s Cold War spy thrillers, and the works of Walt Whitman, America’s poet emeritus.

Now comes another un-put-down-able book, The Postcard, by French writer Anne Berest, who defines her Holocaust work as an “auto-hybrid,” an “autobiography of sorts,” and “a true novel” that she’s wrapped in bits of fiction to protect the grandchildren, still alive, who had nothing to do with the unconscionable crimes committed by their relatives during World War II.

Berest begins her story with a mysterious postcard featuring Paris’ Palais Garnier opera house sent to her mother. On the back are the names of her mother’s grandfather, grandmother, aunt, and uncle — all annihilated in Auschwitz in 1942. No note. No signature. No return address. Most disturbing to Berest was the image of the Opéra Garnier — the central locale of the Nazis during their occupation of France.

“We were terrified [when we received that postcard],” Berest told the New York Post. “For us French people that’s a very strong symbol.” The surge in antisemitism and xenophobia throughout Europe added layers of menace to the card. “All the signs on the postcard were signs of a threat.”

First published in France in 2021 as La carte postale, Berest’s book tells the story of her grandmother, Myriam (nee Rabinovitch) Picabia, who escaped the round-up of Jews in Paris by hiding in the woods. She was later rescued, hidden in the trunk of a car, and driven 50 miles north of Marseilles, where she and her fiancé — and her lover — joined the Resistance, ran messages, and translated illicit BBC broadcasts.

“This [ménage à trois] is actually the part of the book that my mother didn’t really want me to write,” Berest says. “But this sort of love triangle, this three-person romantic arrangement, was one of the most striking things to me…After writing so many difficult pages about dark, dark times [this romance] was a kind of light in the book.”

The Postcard takes readers on the author’s painful journey toward her roots. Having been raised in a secular household, Berest was unfamiliar with Jewish rituals. Yet she was surprised by the frisson of familiarity she felt attending a Passover Seder at the home of her boyfriend. During the evening, he mentioned to guests that Berest’s daughter had recently been wounded by an antisemitic remark at school. When asked what she did about it, Berest admitted that she hadn’t addressed the matter. One of the guests snapped, “The truth, as far as I can tell, is that you’re only Jewish when it suits you.”

The remark stung but eventually pushed Berest into “the dark, dark times” of excavating her roots and claiming her heritage. At the end of her search, she writes:

“All I can tell you is that I’m the child of a survivor. That is, someone who may not be familiar with the Seder rituals, but whose family died in the gas chambers. Someone who has the same nightmares as her mother and is trying to find her place among the living.”

The book, translated flawlessly into English by Tina Kover, became an international bestseller and was longlisted for the Prix Goncourt, France’s most distinguished literary prize. But one of the judges, Camille Laurens, pilloried Berest’s book in Le Monde as “the Holocaust for Dummies.” Laurens slammed the author, young and pretty, as “an expert on Parisian chic” who entered a gas chamber with “her big red sole [Christian Louboutin] clogs.” France’s public radio station rebuked the reviewer for “unheard-of brutality,” and the Left Bank started buzzing.

It turned out that Laurens’ romantic partner, too, was being considered for the Prix Goncourt, also for a book about the Holocaust. He had dedicated his work to a certain “C.L.” who, when criticized for her cruelty, claimed she’d sledgehammered Berest’s book “before” she knew it was longlisted for the prestigious prize. Putride. Vireux. Nauseabond.

The Goncourt immediately dropped both works from consideration and revised its rules, now stating that no lover, relative, spouse, or partner of a member of the jury can be considered for the prize once awarded to Marcel Proust, André Malraux, Simone de Beauvoir, Romain Gary, and Marguerite Dumas.

After that literary storm, The Postcard was blessed with its own double rainbow — widespread critical praise and commercial sales. Both richly deserved.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books