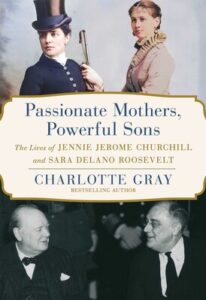

Passionate Mothers, Powerful Sons

by Kitty Kelley

During the pandemic, Charlotte Gray scored a win for women. The Canadian author spent her lockdown days examining the lives of two American mothers previously disregarded by male historians as mere accessories to their world-conquering sons. The result is a feminist take on the women, who’ve been derided and diminished for decades: Jennie Jerome Churchill, once depicted as a fashion-crazed flibbertigibbet, and Sara Delano Roosevelt, dismissed as a wealthy harridan.

During the pandemic, Charlotte Gray scored a win for women. The Canadian author spent her lockdown days examining the lives of two American mothers previously disregarded by male historians as mere accessories to their world-conquering sons. The result is a feminist take on the women, who’ve been derided and diminished for decades: Jennie Jerome Churchill, once depicted as a fashion-crazed flibbertigibbet, and Sara Delano Roosevelt, dismissed as a wealthy harridan.

“They’ve been shoehorned into harmful stereotypes,” writes Gray, “and rarely been portrayed in a sympathetic light since their deaths. In fact, their sons’ biographers often disparage them — it is as though the Great Men of History must spring like Athena, fully formed from the head of Zeus, without tiresome interventions from their mothers.”

Most of those who’ve examined these so-called “great men” are themselves men, including respected biographers William Manchester, author of the three-volume The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill; Andrew Roberts (Churchill: Walking with Destiny); Alan Brinkley (Franklin Delano Roosevelt); and H.W. Brands (Traitor to His Class: The Privileged Life and Radical Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt).

Now comes a reassessment of both in Passionate Mothers, Powerful Sons: The Lives of Jennie Jerome Churchill and Sara Delano Roosevelt. Gray, who’s written 12 literary nonfiction books, is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. Relegated to mining secondary sources of previously published material, she nonetheless manages to bring a compelling view to the life stories of two mothers who influenced the world through their sons.

Both women were unicorns, each one of a kind but complete opposites of each other. Jennie Jerome, who wed Lord Randolph Churchill, was the most famous American heiress to cross the Atlantic and marry a title during the Gilded Age of 1870-1914. As Lady Churchill, she kept her status through three marriages while enjoying numerous dalliances with paramours said to include a Serbian prince, a German nobleman, several British aristocrats, and the prince of Wales, who admired American women because “they are livelier, better-educated, and less hampered by etiquette…not as squeamish as their English sisters.” Jennie became a favorite of the latter, the future King Edward VII, and used her golden contacts to enhance her son’s prospects. As Winston said, “She left no wire unpulled, no stone unturned, no cutlet uncooked.”

Once Winston married, his mother lost her premier place in his life. But whereas Jennie loathed the role of grandmother, Sara Delano Roosevelt reveled in it. On one occasion, when FDR’s two youngest sons were disciplined by having their pony taken away, Sara bought each little boy a horse. Naturally, all the Roosevelt grandchildren adored their grandmother, leaving their mother embittered. As Eleanor Roosevelt wrote years later, “As it turned out, Franklin’s children were more my mother-in-law’s children than they were mine.”

Also unlike Jennie Churchill, Sara Roosevelt enjoyed lifetime access to elite society and did not color outside the lines of proper protocol. Following her husband’s death, the dowager aristocrat donned widow’s weeds and never considered remarriage. Living like a vestal virgin, Sara dedicated herself to her only child, the future American president, following him to Harvard and living near campus so she could see him for dinner once a week. When Franklin married, his mother enlarged her homes at Campobello, in Manhattan, and at Hyde Park to accommodate his growing family, providing them with nannies, maids, laundresses, cooks, and drivers. She even advised her son professionally, counseling him after he won his first political appointment: “Try not to write your signature too small…so many public men have such awful signatures, and so unreadable.”

Spoiled and indulged by adoring mothers, Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt possessed galloping self-confidence that bordered on arrogance and made each insufferable to colleagues. As Churchill said when he returned from the Boer Wars a national hero, “We are all worms, but I do believe that I am a glow-worm.”

Not surprisingly, each of these two egoists had little regard for the other. As FDR told Joseph Kennedy after appointing him U.S. ambassador to the Court of St. James, “I have always disliked [Churchill] since I went to England in 1918 [as assistant secretary of the Navy]. He acted like a stinker then, lording it over all of us.”

Fortunately, their relationship changed when Churchill became prime minister of Great Britain, Roosevelt was commander-in-chief of the United States, and the world was at war. But their closeness — and, indeed, FDR’s prominent place in history — might never have evolved had it not been for the fierce intervention of Sara Delano Roosevelt.

Returning home from London in 1918, Franklin had come down with Spanish flu exacerbated by double pneumonia. His mother and his wife met his ship in New York and had him carried on a stretcher to Sara’s home on East 65th. Street. As the orderlies struggled to make Roosevelt comfortable, Eleanor began unpacking his suitcases and there found love letters from Lucy Mercer. Devastated, she marked that moment as life-changing: “The bottom dropped out of my world.”

Tearfully confronting her husband — as did his mother — Eleanor offered to grant him a divorce. Sara roared back in horror. Furious at her son’s moral lapse, yet fearing the shame a divorce might bring to the family, she declared that if he left his wife, he’d be leaving her as well — and that included Sara’s vast fortune, which supported him, his five children, and his future political prospects. Franklin made the pragmatic decision to remain in the marriage; Eleanor permanently moved out of their bedroom.

Back in London, after years of being chased by unscrupulous money-lenders and litigious creditors, Jennie Jerome Churchill died a grotesque death in 1921. At age 67, she fell down a staircase while wearing a new pair of high heels. “Life didn’t begin for her on a basis of less than forty pairs of shoes,” said Winston’s secretary about Jennie’s unchecked extravagances and staggering debts. Within days of breaking her ankle, gangrene set in, necessitating amputation of her leg above the knee. Lady Churchill soon slipped into a coma and expired, leaving Winston inconsolable. For the rest of his days, he kept a bronze cast of his mother’s hand on his desk.

Sara Roosevelt, however, lived a long and enviable life. She saw a beloved son crippled by polio rise to become president of the United States three times. At his third inauguration, she proudly proclaimed herself “a mother of history,” saying that few mothers ever lived to see their sons elected once. “Why, when you read history it seems as if most of the Presidents didn’t have mothers, the way they fail to appear in the accounts.” At the age of 86, Sara wrote to her son:

“Perhaps I have lived too long, but when I think of you and hear your voice I do not ever want to leave you.”

Alas, Roosevelt’s adoring mother took her final leave on September 7, 1941, and within four years, as he was starting an unprecedented fourth term as chief executive, her “precious son” would follow her at the age of 62 after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage at the Little White House in Warm Springs, Georgia.

In this provocative biography, Charlotte Gray bestows revisionist interest on two “passionate mothers” whose “powerful sons” proved themselves worthy of the maternal love and devotion showered on each.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books