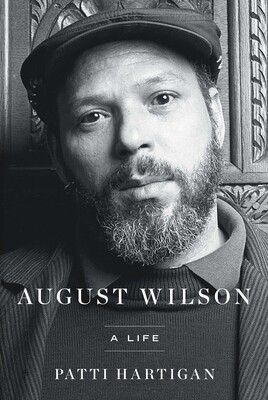

August Wilson

by Kitty Kelley

The celebrated playwright August Wilson (1945-2005) was born Frederick August Kittel Jr. to a Black mother and a white father who abandoned his wife and six children. The fourth child and namesake son was called Freddie, but when his father deserted the family, Freddie took his mother’s surname and became August Wilson. The fatherless child never discussed the scars of being abandoned, but the loss permeated his life’s work.

The celebrated playwright August Wilson (1945-2005) was born Frederick August Kittel Jr. to a Black mother and a white father who abandoned his wife and six children. The fourth child and namesake son was called Freddie, but when his father deserted the family, Freddie took his mother’s surname and became August Wilson. The fatherless child never discussed the scars of being abandoned, but the loss permeated his life’s work.

Wilson adored his mother, Daisy, and desperately sought her approval, but she wanted him to be a lawyer and remained unimpressed by his poetry or even his award-winning plays. “You be a writer when you get something on television,” she told him. The day his play “The Piano Player” aired on CBS’ Hallmark Hall of Fame, February 2, 1995, Wilson gazed up to heaven and thought, “Look, Ma. I did it.” Reflecting on his mother’s passing, the heartbroken son explained:

“It is only when you encounter a world that does not contain your mother that you begin to fully comprehend the idea of loss and the huge irrevocable absence that death occasions.”

Although biracial, Wilson identified as Black and resented any attempt to be defined otherwise. He became irate when Henry Louis Gates Jr. questioned his Blackness in the New Yorker by writing, “He neither looks nor sounds typically Black — had he the desire he could easily pass — and that makes him Black first and foremost by self-identification.” As a playwright, however, Wilson subscribed to the creed of W.E.B. Du Bois, who promoted the four fundamental principles of “real Negro theater”: 1) About us 2) By us 3) For us 4) Near us.

In each of the 10 plays that comprise the Pittsburgh Cycle, Wilson — hailed as “theater’s poet of Black America” — portrays the African-American experience in a different decade of the 20th century. They all opened on Broadway, two of them posthumously:

“Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” 1984

“Fences” 1987

“Joe Turner’s Come and Gone” 1988

“The Piano Lesson” 1990

“Two Trains Running” 1992

“Seven Guitars” 1996

“King Headley II” 2001

“Gem of the Ocean” 2004

“Radio Golf” 2007

“Jitney” 2017

Wilson insisted his plays be produced and performed only by Black artists and denounced “color-blind casting,” asserting that “Blacks have always, historically, been the custodians for America’s hope.” Yet as Patti Hartigan writes — gloriously — in August Wilson: A Life, the first major biography of the man, Wilson’s genius was singular and his work universal, winning him two Pulitzer Prizes and 29 Tony Awards.

While Hartigan, a former theater critic for the Boston Globe, genuflects to Wilson’s monumental talent, she does not spare him his faults. Hypersensitive to slights and given to explosive rages unleashed on waitresses or workmen below him in status, Wilson was an errant husband who married three times and took countless lovers. His first priority in life — above family and friends — was his work. “For him,” Hartigan states, “writing was a force necessary for survival.”

As a high-school dropout with an IQ of 143, young Wilson haunted the aisles of Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Library, where he was relegated to the “Negro section.” He spent hours reading Langston Hughes, Ralph Ellison, and Paul Laurence Dunbar. He described the neighborhood in which he grew up as “an amalgam of the unwanted,” filled with a mishmash of Greeks, Jews, Syrians, Italians, Irish, and Blacks, “each ethnic group seeking to cast off the vestiges of the old country, changing names, changing manners…bludgeoning the malleable parts of themselves. Melting into the pot. Becoming and defining what it means to be an American.”

While Wilson described himself as a “race man,” and all his characters are Black, their stories of pain and sorrow and joy and resentment resonate as shared human verities. “There are always and only two trains running,” he once said. “There is life and there is death. Each of us rides them both.”

Wilson believed that African Americans needed to keep their history alive and cherish their heritage — complete with all its ancestors and all its ghosts. Maintaining that Black culture is unique and worthy of celebration, he sought out Black directors and dramaturges who understood his mission: to celebrate the lives of ordinary Black people.

This was lost on Bill Moyers when he interviewed Wilson in 1988 for the PBS series A World of Ideas. Moyers claimed that Blacks in America needed to embrace the mores of the dominant white culture in order to succeed and suggested that Blacks ought to aspire to the kind of bland middle-class life depicted on The Cosby Show. Those familiar with Wilson’s hair-trigger temper expected him to lay into the obtuse host, but knowing he was on national television, Wilson remained calm and simply remarked that Cosby’s show “does not reflect Black America to my mind.”

Moyers further humiliated himself by asking, “Don’t you grow weary of thinking Black, writing Black, being asked questions about Blacks?” Again, Wilson responded with restraint:

“How could one grow weary of that? Whites don’t get tired of thinking white or being who they are. I’m just who I am. You never transcend who you are. Black is not limiting. There’s no idea in the world that is not contained by Black life. I could write forever about the black experience in America.”

When Cosby gave a speech castigating Black youth for “stealing Coca-Cola” and “getting shot in the back of the head over a piece of pound cake,” Wilson blasted him. “A billionaire attacking poor people for being poor,” he told Time Magazine. “Bill Cosby is a clown. What do you expect? I thought it was unfair of him.”

Hartigan mentions in her author’s note that she had to paraphrase many of Wilson’s intimate letters, early plays, and poems because his estate declined to authorize their use in this book. Still, thanks to prodigious research and significant interviews, including notes from the days she spent with Wilson in 2005 for a Boston Globe Magazine profile, she has crafted a spectacular biography of “a truth teller” whom she eloquently describes as “a griot who accurately depicted the ordinary lives of honorable people whose stories were ignored by the mainstream culture.”

As William Styron once wrote, “A great book should leave you with many experiences and slightly exhausted at the end. You live several lives while reading.” Patti Hartigan has written just such a book about an illustrious playwright.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books