A Trail of Tears and Triumph

by Kitty Kelley

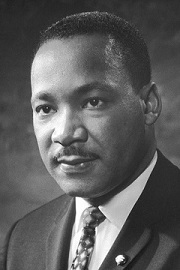

“April is the cruelest month,” wrote the poet T.S. Eliot, and for followers of Martin Luther King Jr., April 4, 1968, was the cruelest day. At 6:01 p.m. on that Thursday, the beloved preacher of nonviolence was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee.

“April is the cruelest month,” wrote the poet T.S. Eliot, and for followers of Martin Luther King Jr., April 4, 1968, was the cruelest day. At 6:01 p.m. on that Thursday, the beloved preacher of nonviolence was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee.

Hours later, riots erupted throughout the country as angry mobs smashed windows, trashed stores, and blew up cars, leaving dozens dead and more than 100 cities smoldering. President Lyndon Johnson finally summoned the National Guard to restore order.

More than five decades later, some scars remain, but Dr. King’s dream of a beloved community still shines, even in the poorest pockets of the country. I recently joined Stanford University’s “Following King: Atlanta to Memphis” tour, led by Professor Clayborne Carson, senior editor of The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Vols. I-VII. Traveling by bus for a week — masked, in the era of covid — we patronized only minority-owned hotels and restaurants.

We began in Atlanta with a visit to Dr. King’s last home, the one he purchased after winning the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize. We toured the National Center for Civil and Human Rights and learned from a freshman at Morehouse College why he values his education on the 61-acre campus of one of America’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU), which is close to Spelman College, an HBCU for women:

“We both fall under the umbrella of Atlanta University Center, so we can attend classes on either campus…Our slogan here at Morehouse is ‘Let There be Light,’ and while it’s prevalent in my generation [Class of 2025] not to speak your mind lest you be canceled, here, people are not making fun of you or out to cancel you. They tell us: ‘Say your ignorance in class so you don’t say it in the world.’”

Before leaving Atlanta, we visit the Ebenezer Baptist Church, the spiritual home of Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, where the Rev. Raphael G. Warnock now serves every Sunday as pastor. The rest of the week, he serves as Georgia’s junior senator in the U.S. Senate.

Boarding the bus, we headed for Montgomery, Alabama, home of the Confederacy, where we visit the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, created by Bryan Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), the nonprofit that guarantees the defense of any prisoner in Alabama sentenced to death. For many of us, this is the most upsetting museum on the tour because it forces you to see the terrible connection between 1865 and today.

The EJI has identified more than 4,000 Black men, women, and children who were lynched. At the site’s center hang 800 rusted steel monuments, one for each county in the U.S. where documented lynchings took place. Entering the museum, we were confronted with replicas of slave pens, where we saw and heard first-person accounts from enslaved people describing what it was like to be ripped from their families and await sale at the nearby auction block. We learned what “sold down the river” means: Many enslaved people were punished with a transfer from the North to harsher conditions in the South. Etched in bronze is Harriet Tubman’s quote, “Slavery is the next thing to hell.”

On a nearby street corner, we meet the artist Michelle Browder, who showed us her outdoor gallery honoring “Mothers of Gynecology”; her 15-foot-high sculptures depict three enslaved women subjected to brutal experiments for “supposed” medical advancement.

From Montgomery, we were bused to Birmingham (aka “Bombingham”) and the 16th Street Baptist Church, where four little girls were killed by a bomb as they prepared to sing in their choir on September 15, 1963. The pastor’s undelivered sermon that Sunday was entitled “A Love that Forgives.”

Weeks before, 300,000 people had gathered peacefully on the National Mall in Washington, DC, to hear Dr. King’s soaring “I Have a Dream” speech. Later, he was jailed in Alabama. While there, he wrote his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail” on scraps of paper and bits of toilet tissue that his lawyer smuggled out piece by piece on each visit. Dr. King’s message berated white moderates “devoted to order, not to justice,” particularly those white church leaders “more cautious than courageous.”

From Montgomery, we traveled to Selma to meet our no-nonsense guide in the projects. “We’re in the ‘hood now, so if you hear a pop-pop, duck,” she said. People on the bus squirmed as she delivered her blunt commentary:

“Selma is a city of barely 20,000, and 80 percent of us are African American, still living in the poorest wards…Voting registration has shrunk because folks ask, ‘What’s voting done for us?’ We’re a broken economy, a broken community…Hate groups study us as a failed model of Democratic policies.”

Rain fell as we walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, named for a Confederate general and Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan and the site of “Bloody Sunday,” March 7, 1965, when police attacked Civil Rights marchers with horses, clubs, and tear gas.

We later stopped in Meridian and Jackson, Mississippi, enroute to Memphis, where we visited the Lorraine Motel, with its white plastic wreath of blood red roses marking the spot on the second-floor balcony where Dr. King was assassinated. The plaque beneath reads:

“They said one to another,

Behold, here cometh the dreamer,

Let us slay him

And we shall see what will become of his dream.”

– Genesis 37.19-20

The motel site has been expanded into a complex of buildings incorporated as the National Civil Rights Museum in 1991, the first in the U.S. dedicated to telling the Black Civil Rights story. It’s also been called “The Conspiracy Museum” because its second floor, entitled “Lingering Questions,” chronicles the capture and arrest of James Earl Ray and explores myriad conjectures about whether Dr. King’s killer acted alone.

Outside on the street, a tiny woman named Jacqueline Smith protests the $27 million museum complex. She weighs no more than 90 pounds, but her outrage is ferocious. She’s been standing on the corner every day since 1988, when she was evicted from the motel to make way for the museum’s construction.

“What’s the point of all this?” she asks. “What does this rich museum offer the needy, the homeless, the poor, the hungry, the displaced, and the disadvantaged? Dr. King said: ‘Spend the necessary money to get rid of slums, eradicate poverty.’ This museum was built with non-unionized labor. Dr. King was all for unionized workers. This museum celebrates his murderer… does the John F. Kennedy Library celebrate Lee Harvey Oswald?”

Someone starts to speak, but Jackie brooks no interruption. “Why don’t you white people do what’s right for a change?”

Quietly, we return to our bus, edified by Dr. King’s vocal disciple.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books