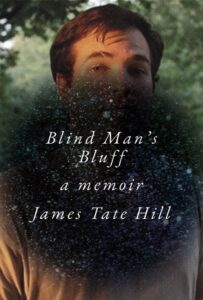

Blind Man’s Bluff

by Kitty Kelley

Some memoirs flicker like fireflies on a summer night. Others pierce your psyche with their subjects’ tortured experiences, consequent miseries, and — finally — their oh-so-glorious survival. The Story of My Life by Helen Keller, Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt, The Liars’ Club by Mary Karr, Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou are among the memoirs that leave you breathless; they’re books you keep and don’t pawn off on your neighbor’s yard sale.

Some memoirs flicker like fireflies on a summer night. Others pierce your psyche with their subjects’ tortured experiences, consequent miseries, and — finally — their oh-so-glorious survival. The Story of My Life by Helen Keller, Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt, The Liars’ Club by Mary Karr, Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou are among the memoirs that leave you breathless; they’re books you keep and don’t pawn off on your neighbor’s yard sale.

Now comes another keeper: Blind Man’s Bluff by James Tate Hill. With his pluperfect title, Hill winningly recounts his life after he was declared legally blind. “I was ready for a change, ready to be changed, but the loss of my sight that month before turning sixteen wasn’t what I had in mind,” he writes.

After being diagnosed with Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, a genetic condition that causes gradual blindness mostly in men, Hill burrows into denial and bluffs his way through blindness until his mid-30s. Armed with a basketful of euphemisms for his affliction — “sightlessness,” “print disabled,” “limited seeing,” “bad eyes,” “blurred vision” — he forges ahead, psychologically unable to accept a world of white canes and seeing-eye dogs.

He refuses to admit to himself, his teachers, his friends, and even his first wife that he is blind. “Not speaking of it, not reminding others of it, not letting it hang like a banner above my head let me almost forget, and to almost forget was to make it almost untrue.”

Some days in school, he lets himself be docked for absence rather than risk signing his name over another student’s on the attendance sheet. In classes, he pretends to take notes, scrawling pages of gibberish that he later throws away. Poignantly, he lines the shelves in his apartment with books he can’t read while hiding his Talking Books under the bed:

“I was aware of the stigma associated with books on tape. Jokes on sitcoms implied audiobooks were to physical books what flag football is to the NFL.”

Reading this memoir makes you realize how much you take sight for granted. Just being passed a plate of food can be fraught for a blind person. “So many things can go wrong,” Hill explains, “not limited to my thumb and forefinger landing in the wrong section of the plate; touching, defacing or possibly knocking onto the floor a brownie or precariously arranged cheese on a cracker, or, the Grand Guignol of canapes, a chip that must be sent on a recon mission into a dip of unknown depth or viscosity.”

Crossing the street becomes a potential dance with death:

“In daylight, you can’t rely on headlights and traffic lights to know when it’s safe…Sometimes other pedestrians are waiting on the curb, and you can cross behind them…At night when there are no pedestrians to whom you can pin your safety and no traffic lights or stop signs to part traffic, you can listen for cars.”

One day, Hill nearly loses his life when he changes his route and crosses on what he thinks is a green light, and then “a car horn punches a hole in the morning,” as he stumbles to a concrete island, escaping “almost death.”

Hill’s story is funny and sad at the same time, and raw in its honesty as he recounts the rejection by his first wife, who initiates divorce proceedings after six years of marriage. Both had cultivated facades: His was having vision; hers was having an outgoing personality. Alone with him, she clams up and resents his dependence as much as he hates being dependent. Despite having earned three master’s degrees, he cannot earn a living as a writer, and only barely as a teacher, forcing her to become the primary breadwinner.

“I wished I were a man capable of leaving a bad relationship,” he recalls, “but I barely found the courage to leave the apartment.”

After his second novel is rejected, Hill identifies with Paul Giamatti’s character — a divorced, unpublished novelist — in the film “Sideways.” But then Hill rallies, reactivates his online-dating account, and somersaults into a relationship that finally makes him feel secure enough to stop bluffing. Once he drops his pretense and admits his disability, he finds happily-ever-after endings as a person, a teacher, and a husband.

In the book’s last chapter, entitled “Basketball,” Hill and his new wife are in a gym playing hoops. They chase down rebounds and launch wild jumpers and crooked free throws, laughing as they miss nearly every shot.

“Every once in a while a three-pointer rattles in, and we scream our heads off,” Hill writes, “champions after a last-second shot.”

Champions, indeed.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books