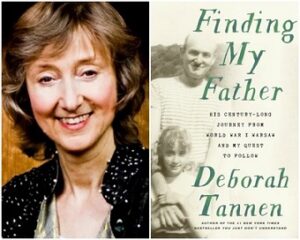

An Interview with Deborah Tannen

by Kitty Kelley

Deborah Tannen, a professor of linguistics at Georgetown University, has just published her 13th book, and first memoir, Finding My Father: His Century-long Journey from World War I Warsaw and My Quest to Follow. We recently discussed the new work.

You’ve written many books (including You Just Don’t Understand, You’re Wearing THAT?, You Were Always Mom’s Favorite!, and You’re the Only One I Can Tell) about how people express/hide themselves through language. How did the commercial success of those books enhance or detract from your position in academia?

You’ve written many books (including You Just Don’t Understand, You’re Wearing THAT?, You Were Always Mom’s Favorite!, and You’re the Only One I Can Tell) about how people express/hide themselves through language. How did the commercial success of those books enhance or detract from your position in academia?

My colleagues at Georgetown and in my discipline have been uniformly supportive of me and my academic, as well as my general-audience, writing. I feel I should add “kunnahurra,” which is how my mother pronounced the Yiddish expression one says to avoid jinxing good fortune.

How did writing this book about the father you adored affect you?

My father was the parent I felt an affinity for, the one I thought understood me. But when I was a child, he was rarely home. The strongest presence I felt in the house was his absence. The hours upon hours I spent talking to him about his life after he retired — I have 200 cassette tapes! — began to make up for that deep sense of longing. He also gave me mountains of written words: journals he kept before he married; letters he saved and copies of letters he wrote; and memories he wrote down for me, especially about his childhood in Warsaw (where he was born into a Hasidic family in 1908), but also about his life after he came to the U.S. in 1920. These all helped me see how his life was affected by and reflected the cataclysmic events of the 20th century: how WWI affected Warsaw’s Jews, immigration, the Depression, and anti-Semitism in both Poland and the U.S. between the wars.

My father’s father died of tuberculosis when he was very young — he never knew his father — so [my father] quit high school at 14 to support his mother and sister. Yet he became a lawyer, established the largest workers’ compensation firm in New York City, and ran for congress. Until I was in junior high, my father worked as a cutter in a coat factory. After that, my father was a partner in his own law firm. I always knew these outlines but had no idea how or why it happened that way, what it all meant, day to day, how he felt about it, or why it took him 30 years from passing the bar until he could support his family through law. Figuring it out gave me a clearer sense of how I was shaped by history, too.

Why do you think your father chose you to write his memoir rather than one of your two sisters? And has publication of this book affected your relationships within your family?

It was a no-brainer. I was already a published writer, having gotten a love of language and of writing from him. And my adoration was obvious. My sister Mimi once said, “I love Daddy, too, but I don’t think he’s God!” She and my sister Naomi have always been part of this project. I checked memories with them, and whenever I found something surprising, I’d share it with them. Our memories differ, of course. Naomi is six years older than Mimi and eight years older than me, so she had our father to herself when she was small. Naomi, like me, tended to idealize him and be critical of our mother. Mimi has been an invaluable reality check. She’ll point out when I’m judging our mother too harshly and letting our father off the hook.

As an immigrant from WWI Warsaw, your father did not have an easy life. His father died young; his mother sounds like a harridan; and he worked at over 60 jobs to support her and himself and his family. Yet he lived to be 98. To what besides good genes do you attribute his longevity?

Good luck. His and mine.

You discovered a secret relationship of your father’s and entitled one chapter “The Hidden Letters” after finding correspondence that he had secreted away for decades. Please describe.

Ah, yes, the woman I call Helen. She wasn’t a secret, but the fact that he’d saved her letters was. Both my parents spoke openly and casually about my mother’s “rival.” My father once said, “Your mother wasn’t my girlfriend. Helen was my girlfriend.” So why did he marry my mother and not his girlfriend? When he told me he’d saved Helen’s letters but didn’t know where they were, I longed to find them, to figure that out. I eventually did find them — along with copies of many letters he wrote to her! Reading their correspondence, I fell in love with Helen myself. I saw that my father’s relationship with her was romantic in a way his relationship with my mother wasn’t. And I was able to piece together the dramatic events that led to his marrying my mother. I felt I’d solved a mystery and learned a lot about relationships between women and men at the time, especially the fraught role played by virginity!

Your father was a communist, an atheist, and a Zionist. Can you say a bit about each and explain how each weaves into the other?

My father already identified as all three when he came to the U.S. at 12. He was influenced by the Bolshevik revolution through his mother’s youngest sister. Only six years older than my father, Magda was like a big sister he looked up to. Like many young people in every generation, she and her friends saw poverty and injustice and wanted to build a better world. Communism promised that would come when workers of the world unite and saw religion as a barrier to that solidarity. So atheism and communism went together. My father became disillusioned with communism but became an ever-more passionate supporter of Israel as he saw what happened to the members of his family who were still in Poland at the start of WWII. He remained a devout atheist with a deep and proud Jewish identity. When he was old, I asked, “Do you feel more Polish or American?” He replied, “I feel like a Jew.”

What advice would you give to your students about writing a memoir, particularly those who, unlike you, don’t have the advantage of hours and hours of taped interviews?

Talk to anyone you can find who knew your family or lived through similar times. Follow every trail wherever it takes you — to other people you can talk to, any documents you can find, and the infinite pathways now available on the internet. And write your own memories down for the next generation!

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books