L.E.L.

by Kitty Kelley

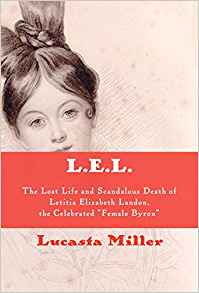

L.E.L.: The Lost Life and Scandalous Death of Letitia Elizabeth Landon, the Celebrated “Female Byron” is the titillating title of Lucasta Miller’s biography of a 19th-century poet few people remember, if they’d ever heard of her. The title teases, as does the scarlet banner on the cover once used for X-rated magazines sold under the counter.

L.E.L.: The Lost Life and Scandalous Death of Letitia Elizabeth Landon, the Celebrated “Female Byron” is the titillating title of Lucasta Miller’s biography of a 19th-century poet few people remember, if they’d ever heard of her. The title teases, as does the scarlet banner on the cover once used for X-rated magazines sold under the counter.

The cover features a gauzy sketch of a sweet-faced young woman with old eyes and rosebud lips that barely smile. Her long, brown hair is swept up into an intricate arrangement of silken folds and a braid that, if unloosened, promises to tumble to her waist.

The impression is soft but suggestive. In fact, if the book did not carry the august imprint of Knopf, you might expect a Harlequin romance novel. The book cover introduces the life story of an unfortunate woman with talent born in an unfortunate time when, as she wrote:

“None among us dares to say

What none will choose to hear.”

Women of her era dared not put themselves forward on an equal footing with men and appear unladylike. So, to circumvent the strictures of society, many female writers used male pseudonyms to get published: George Sand (Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin), George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans), and Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell (the Brontë sisters — Charlotte, Emily, and Anne, respectively, who preserved their initials). Even Louisa May Alcott wrote her dark love stories under the name of A.M. Barnard.

Letitia Elizabeth Landon became L.E.L. and, as such, she published novels, criticism, and reams of poetry, becoming the toast of literary London.

To ensure her success, she hitched her bright star to a male mentor, the married editor of the Literary Gazette, who published her poetry and paid her a pittance. He promoted her career, reveled in her celebrity, and became her lover, at one point moving her into his home with his wife and children.

Letitia bore him three children, all of whom had to be given up for adoption, such were the mores of the time for an unmarried woman. L.E.L.’s affair with the libertine editor remained secret until 1826, when the Sunday Times published a story headlined “Sapphics and Erotics,” and quoted the editor’s charwoman, who recounted in explicit detail seeing the adulterous couple “in flagrante.”

Author Miller, a British literary critic, contends the reason most people have never heard of L.E.L. is because she was ahead of her time and, not to put too fine a point, was “a fallen woman” whose life was considered so scandalous that her friends tried to shield her from her own infamy.

L.E.L. poured her life into her poems and, after the Times’ exposé, the public read them as confessionals of lust, love, and shame. Her flowery verses dwelled on gothic death, breathless passion, and unrequited love, all a part of her sad existence.

Others suggest that L.E.L.’s talents were more limited than those of Byron, Shelley, and Keats, her male contemporaries, and, thus, didn’t deserve their posterity. Some scholars maintain that L.E.L. got lost in “the strange pause” between the Romantic Age of Byron and the pre-Victorian era of Dickens, who ridiculed L.E.L.’s literary salons and her “rickety sentimental poetry” in The Pickwick Papers.

In her acknowledgements, Miller states that she spent nine years “entangled on and off” in researching and writing this book. The extensive research shows, but so does the entanglement in writing that is dense and academic.

Throughout, she sprinkles her prose with droplets of French: au fait, raison d’etre, cri de couer, de rigueur, cordon sanitaire, femme libre, succes de scandale. After plowing through 320 pages of small type, plus 54 pages of notes and bibliography, one wonders if the author was trying to refashion her Ph.D. thesis for the commercial market.

Like a student bewitched by her research, Miller provides every exhaustive detail about L.E.L. and her lovers, friends, neighbors, and, in one section, a farflung Irish relative, whose “most significant love affair was with the French courtesan-actress Hyacinthe Varis, which produced an illegitimate daughter, Hyacinthe-Gabrielle Roland, who also appeared on the stage, before becoming the mistress of the Duke of Wellington’s brother, the Earl of Mornington.”

Whew.

Miller then bangs on about L.E.L.’s abandoned children, dependent clergyman brother, envious contemporaries (all men), cowardly first fiancé, who bailed on account of the Times story, and the Pygmalion editor who traded her in for a teenage Galatea.

No wonder poor L.E.L., having been exiled from London society and living her last few weeks with an abusive, slave-trading husband on the coast of West Africa, swallowed poison at the age of 36 to end her misery. And ours.

Merde!

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books