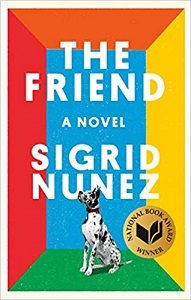

The Friend

by Kitty Kelley

If The Friend by Sigrid Nunez, a 2018 National Book Award winner, slipped under your reading radar, run — don’t walk — and grab this 224-page treasure, which you’ll gobble in joyous gulps.

If The Friend by Sigrid Nunez, a 2018 National Book Award winner, slipped under your reading radar, run — don’t walk — and grab this 224-page treasure, which you’ll gobble in joyous gulps.

Your reward will be an elegiac read about love and life and death and grief. The sparse prose sparkles and draws you in, making you feel as if you’re reading intimate revelations from the diary of a woman who’s been slammed with horrific news: Her beloved friend, mentor, and one-time lover has committed suicide.

The deceased has left behind three wives, many former lovers, no children, and one huge dog: a Harlequin Great Dane named Apollo — the only named character in the book. Wife Three foists Apollo off on the narrator, who, against her better judgment and the “No Pets” rule of her New York City apartment, takes the 180-pound hound, but vows the custody is temporary.

As a writer, the narrator uses her journal to try to understand the awful why of suicide, and the reason her friend, who was not suffering from a terminal disease, chose to end his life. She seeks answers from Wife One, Wife Two, and Wife Three, but, getting none, she begins to read about suicide.

She learns that those who drown themselves for love in the Seine tried to scramble out of the water, but those who drown because of financial ruin sank like stones. She is taken aback when she learns that writing in the first person, as she is doing in her journal, is a known sign of suicide risk. Another predictor is knowing a suicide victim.

Desperate to shake off the tentacles of grief, she turns to a therapist and explores her relationship with the deceased. We never know the dead man’s name, but we learn that he was a handsome professor with hazel eyes who could not bear to be alone. He spoke with a BBC accent and regarded his classroom as his sexual playpen.

In her journal, the narrator quotes W.H. Auden, who said he did not like men who leave behind them a trail of weeping women. She then addresses the dead man: “Auden would have hated you.” She chides him for being “restless, priapic,” and for allowing his sexual romps to threaten his career, his livelihood, and his marriages.

She speculates that his mirror might have presented the ugly truth he could not accept, and the blow to his vanity proved to be fatal. Seeing that he had aged beyond his ability to seduce, he lost his will to live. “A power has been taken away, it can never be given back again,” she writes.

Then she pauses to wonder “why we call a womanizer a wolf. Given that the wolf is known for being a loyal, monogamous mate and devoted parent.” She writes that beyond his self-conceit, the deceased was out of step with his students, especially the young women he called “dear,” who did not revere literature as he did, and certainly did not revere him.

She posits that perhaps his suicide saved him from being shamed by the #MeToo movement, and she wonders if he decided it was better to exit life by his own hand than continue living in a world that no longer valued him or his work.

There is no intricate plot that holds this lovely book together other than the bond that develops between a dog and his owner, which eventually leads both to comfort and consolation over their shared loss. Their immutable connection is something all animal lovers will understand.

As a writer in residence at Boston University, and having taught writing at Princeton, Amherst, Smith, and Columbia, Nunez allows her narrator to hold forth on writers and writing, and her narrator does not hold back. She raps students from top schools who cannot write a sentence, and thumps those who refuse to read a writer who has a bad habit or a tiny eccentricity:

“I once had an entire class agree that it didn’t matter how great a writer Nabokov was, a man like that — a snob and a pervert, as they saw him, shouldn’t be on anyone’s reading list.”

Such provocative observations will make the book intoxicating for some, while others may find too much exclamation about writers and writing and writing seminars, but that is the life shared by the narrator and the deceased — their love of literature and the books that enriched their lives.

I was enthralled by Nunez’s many literary references and the way she folds in Isak Dinesen and Toni Morrison on the subject of grief and, a few sentences later, glides into Henry James and Philip Roth on the agony of writing.

In between, she summons insight from Milan Kundera and his interpretation of Genesis. She traverses from Tolstoy to Lady Gaga with style and grace, and fittingly quotes Flannery O’Connor, who said: “Only those with a gift should be writing for public consumption.”

Sigrid Nunez has such a gift.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books