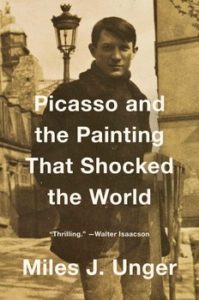

Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World

by Kitty Kelley

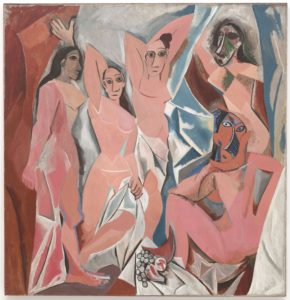

I had no idea until I read Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World by Miles J. Unger that Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” was so shocking. After visiting the Musée National Picasso in Paris last week, I would’ve pinned that ribbon on “Guernica” (1937), his mammoth evocation of the horrors of war. (Obviously, I missed the memo proclaiming sex more shocking than man’s inhumanity to man.)

I had no idea until I read Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World by Miles J. Unger that Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” was so shocking. After visiting the Musée National Picasso in Paris last week, I would’ve pinned that ribbon on “Guernica” (1937), his mammoth evocation of the horrors of war. (Obviously, I missed the memo proclaiming sex more shocking than man’s inhumanity to man.)

Strictly translated, “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” means the young, unmarried women of Avignon — the ancient town in southeast France in the Vaucluse, on the left bank of the Rhone. But elementary French does not capture Picasso’s revolutionary painting meant to rivet and revolt. As he said, “Art is not made to decorate apartments…It is an instrument of offensive and defensive war against the enemy.”

In 1907, Picasso’s enemy was “the centuries-old tradition” of art, which he attacked with his full artillery, producing a wall-size painting of five androgynous nudes with knife-sharp breasts, misshapen heads, and hollow eyes that looked fatigued and fed up with the sexual demands of their paying customers.

For Picasso, “Les Demoiselles” encompassed a narrative of lust and rage and repulsion and illicit desire. He stripped sex of all romance and displayed the brothel business as a basic transaction of cash for services rendered.

“Indeed, the dynamic interplay between the constructive and destructive principles, Freud’s Eros and Thanatos, was the key to the artist’s creativity,” states the author. At the time, those accustomed to the idealized nudes of Botticelli’s “Venus” and the soft Madonna curves of Raphael did not see Picasso’s masterpiece as creative, but rather as dark, disruptive, and dystopian.

In fact, he was shunned by his adoring bohemian disciples (aka, bande a’ Picasso), who were horrified when he pronounced the painting his glorious “exorcism.” Henri Matisse, his main rival among avant-garde artists in Paris, denounced “Les Demoiselles” as a crime against art, an elaborate hoax, and a personal affront. Dealers and collectors fled, showing only disgust for the painting.

One left Picasso’s studio practically in tears, telling Gertrude Stein, the artist’s biggest patron: “What a loss for French art!” Gertrude’s brother, Leo, once a Picasso patron, called the painting “a horrible mess.” Picasso so scandalized the art world by his depiction of these hard-edged prostitutes that, after one studio showing, he rolled up his canvas and stashed it under his bed for nine years until the world caught up with his vision that introduced the school of painting known as Cubism.

Given the heaving shelves of Picasso books, and the fourth and final volume of the artist’s life to be published soon by Sir John Richardson, one has to applaud Unger, an art historian, for carving his own niche in the adoration wall that surrounds Picasso’s genius.

While the author genuflects to the artist’s protean talents, he does not spare the man holding the paintbrush. Unger describes Picasso’s whorehouse as “the great battlefield of the human soul, an Armageddon of lust and loathing but also of liberation, the site where our conflicted nature reveals itself in all its anarchic violence.”

Some might wish Unger had grappled more vigorously with Picasso’s misogyny and his well-documented cruelty to women, but his savagery remains palpable on the page. “An unrepentant male chauvinist,” Unger calls him, Picasso used and abused women, discarding wives, mistresses, and lovers like a snake shedding its skin. His art was his first priority in life. Everything else — family, friends, children, even pets — was sacrificed on the altar of his raging ambition.

At one point, Picasso and Fernande Olivier, his first true love and mistress of many years, decided to adopt a 13-year-old girl from a Paris orphanage. Within weeks, we learn, “Picasso’s feelings veered dangerously far from the paternal.”

A sketch he titled “Raymonde Examining Her Foot” shows her spreading her legs to Picasso’s devouring gaze. “There’s no indication that Picasso ever abused Raymonde,” writes Unger, “but it’s clear she aroused feelings in him that might have led to disaster. His attraction to adolescent girls, at least later in life, is well-documented.”

The youngster lived with Picasso and Fernande for four months, during which time he was working on “Les Demoiselles.” Then they decided a child was too much of a strain on his art and their relationship, so they returned Raymonde to the orphanage, discarding her along with her dolls.

One of the artist’s most despicable acts occurred in 1944, when Picasso, a Spaniard living in Paris during World War II, was spared military service. Famous and influential at the time, he refused to help his lifelong colleague Max Jacob, Jewish and homosexual, who, the author tells us, “died at Drancy while awaiting transfer to Auschwitz, after Picasso failed to intervene on behalf of his old friend.”

The young prodigy from Barcelona lived to be 91 years old. He became rich beyond his imaginings and made himself the most renowned artist of the 20th century, but he was hardly a man beloved. Like his art, Pablo Picasso never tried to please.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books